Читать книгу Lime Creek Odyssey - Steven J. Meyers - Страница 8

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The contemporary mind seems to have reserved a rather distant and peculiar place for nature. Some (the least perceptive among us) feel that nature is simply the place where we find the resources to fuel our existence. Some feel compelled occasionally to travel to this place called nature in order to restore their mental health or to learn the lessons that nature has to teach. We are surrounded by magazines, books, and documentary films that show us the incredible value, beauty, richness, and diversity of a distant nature. In each case—as a thing to be exploited, a place to visit, or a place from which to learn—nature exists as something separate from ourselves.

Humans have walked upon the earth for countless millennia, but for most of that time travel was limited. Magazines, books, and films did not exist. Exposure to distant places and events did not occur. Each individual had access to his own observations and his own immediate place. Shared experience took the form of a cultural inheritance, embodied in slowly evolving rituals and oral tradition. These too were rooted in place. Even those who ranged through a relatively wide expanse of terrain—moving with the seasons, following good weather, and migrating game—moved at a pace slow enough to allow a constant sense of immediacy. Nature, I suspect, would have been a foreign concept in this context. Life absorbed it, and it could not be conceived of as a separate entity. I believe there are advantages to be had in regaining this perspective.

Contemporary literature reflects the values of the societies within which it flourishes. Much writing ranges widely, explores the distant, details the strange, and revels in the obscure. The tendency is not strictly modern. We find evidence of it for as long as there has been literature. Homer expressed the Greek heroic ideal by sending Odysseus off to a distant war and then on a roundabout journey home. His travels to faraway lands were filled with discovery, and we are led to believe that such a life brings great knowledge. Appearing much less heroic and learned in these tales was Penelope, who waited at home for the return of her husband.

Contemporary ideals of heroism, greatness and significant exploration seem to follow the Greek heroic model. Discoveries aren’t discoveries at all unless they are made far from home in an exotic land. Yet when I think of Odysseus and Penelope, it is not the warrior-traveler who commands my respect and admiration. His heroism was often the result of circumstance and even more often the result of foolhardiness and bravado. He shows little evidence of profound knowledge or wisdom. Are we to believe that Penelope really did nothing for twenty years but weave or that she learned nothing while waiting for the return of the conquering hero? I think it more likely that her time was filled with an exploration of a vastly more significant place—her home—and that her thoughts, not occupied by repeated immediate threats to life and limb, were occupied with far richer responses than fleeing or fighting. Her journey, as yet unrecorded, was probably at least equal to that of her better-known husband, and the lessons we might learn from her odyssey are perhaps more significant.

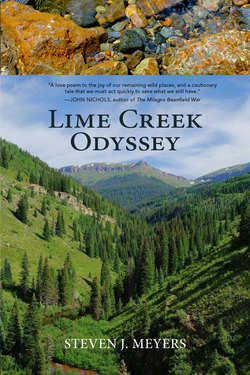

“Lime Creek odyssey” might appear to be something of an oxymoron. Like British cuisine and military intelligence, a Lime Creek odyssey seems to make little sense. The physical setting is too small. Within the perspective of an earlier time, however, the title makes a good deal of sense. An odyssey need not involve a long journey, simply a profound one. A place need not be exotic in order to serve as a springboard for discovery. In fact, I wonder if long journeys serve us as well as explorations of our own homes. Perhaps it is best to explore the meaning of place at our doorstep.

Lime Creek is both a place and an emblem. For me it is a distillation of the character of a region I know as home and within which I live. It is neither far away, nor separate from me. We live here, together.

The creek is not particularly long or broad. Its main stem travels roughly twelve miles from its headwaters (a few miles southwest of Silverton, deep in the heart of the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado) to its terminus at the confluence with Cascade Creek. Its width ranges from a few feet at its beginnings to the twenty-five-foot or so width of its widest shallow riffles. Yet of all the streams I have sat beside, walked along, or waded through, I find it the most powerful in experience and memory.

It begins in the glacial cirques of high peaks and never leaves the mountains, but the terrain and climatic zones it travels through are quite varied. It can be a calm meander through a lush mountain meadow or a tumultuous roaring torrent through a narrow, rock-walled gorge. Its banks can be stark with the limited but beautiful life of the tundra, or they can be verdant with the complexity of a mountain forest nourished by rich moist soil. In short, Lime Creek is everything a mountain stream should be.

In the San Juans there are more remote streams that are just as varied and beautiful. There are less accessible streams that lend credence to the illusion that a personally discovered stream belongs to you and you alone. A highway follows the course of the Lime Creek valley and a dirt road meanders beside the stream where the deep gorges give way to gentler terrain. In an area so dominated by wilderness, it must seem strange that this relatively accessible creek should become an emblem of place.

The history of man in the San Juans is long and complex. Utes hunted here and lived among the peaks long before Europeans arrived. The Spanish came from the south and other Europeans came from the east during the period of preliminary exploration that ended rather abruptly with the Civil War. After the war, prospectors and miners, road builders and railroaders came to extract the gold and silver found in the rocky veins of the heavily mineralized mountains. They carried it away on the backs of mules, in horse-drawn wagons, and railroad gondola cars. As towns were established, civilization soon followed.

To ignore the presence of man here would be naive, but there is wilderness here too—land that shows little evidence that man exists. The San Juans, like many other wild places, straddle the border between wilderness and human habitation. Lime Creek, wild yet well explored, is a manifestation of this truth. It is not my private stream, no matter how compelling the illusion may be. The creek helps me to remember that even apparently undiscovered, remote streams do not become mine alone upon discovery.

Beyond Lime Creek’s varied terrain and habitat, beyond its existence as a wild yet known place, Lime Creek embraces all that the San Juans are for me because it is a place where I have spent a great deal of time. I have waded the streambed, walked the woods, and climbed many of the peaks surrounding the valley. From here the creek leaves the mountains to join the ever-increasing flows that eventually become the Pacific Ocean. Here in the San Juans, however, it is a headwater, a source—a good place for the discovery of one’s own roots and meaning.

It seems appropriate for me to wander this little valley while others, more heroic, journey to Nepal, the Arctic, the tropical rain forest. This personal odyssey of place, this exploration of a mountain stream, is also a journey in the discovery of self, and a search for an appropriate definition of man’s place in the broader reality of nature. I stay at home, like Penelope, believing that one’s home is the proper place for such an odyssey.