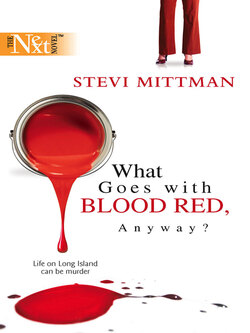

Читать книгу What Goes With Blood Red, Anyway? - Stevi Mittman - Страница 9

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеDesign Tip of the Day

The most neglected area of any house tends to be the ceiling. Look up. Now imagine what antique mirror tiles on your library ceiling could do (click here). Imagine baby-pink and apple-green circus stripes that extend down 12 inches onto the walls of your baby’s room (click here). Imagine ornate white molding against a deep blue ceiling in your dining room (click here). Imagine a field of flowers over your bed (click here) achieved simply by stapling sheets to the ceiling and running ribbon over the seams. Look up again—what do you see?

—From TipsfromTeddi.com

Elise Meyers’s eyes are staring at the ceiling I’ve designed for her new kitchen. It’s a Marrakech-bazaar tromp l’oeil sort of thing. She’s lying on the newly tiled but not-yet-sealed terra-cotta floor in a getup that men in dark theaters wearing wrinkled raincoats can only dream about, and I can’t really tell how she feels about the work I’ve put my heart and soul into.

“So, what do you think?” I ask, fingers crossed, breath held, staring up at the ceiling myself. She doesn’t acknowledge me, doesn’t even blink. I suppose she just doesn’t understand how important this is to me, that this new business I’ve started isn’t just a job. It’s security, self-respect, sanity. “You hate it. I can change it. Just tell me what you don’t like. Is it the colors? The red is a little soft with the mustardy gold. Maybe it could be deeper—”

She just keeps staring at the ceiling, ignoring me. I mean really, how can I fix things if my clients don’t tell me what’s wrong? I’m not a mind reader.

“Elise?”

I stamp my foot, trying, I suppose, to snap her out of her reverie, or stupor, or whatever it is. Only she still doesn’t blink.

And then I notice the trickle of blood.

“I should have known,” I mumble, more to myself than to Detective Harold Nelson of the Nassau County Police Department, who is taking down my statement. He is keeping one eye on me and the other on his partner, who is donning rubber gloves and kneeling over the body of the very scantily clad Elise. “Maggie May was waiting by the open door, and I thought, ‘I’ll probably find Elise dead….’”

“Maggie May?”

I gesture with my head toward a pathetic little ball of white fluff whimpering on her little red monogrammed L.L. Bean bed in the dining room. The detective appears to melt. I’d have pegged him for a mastiff man, which just shows how much I know about men.

“Right,” he says. “So you thought she’d be dead because…?”

I hesitate. There’s a uniformed policeman investigating the new vegetable sink that was supposed to be installed today—a hammered copper bowl that just sits on the center-island counter with a faucet poised over it. The idea was for it to make you actually want to eat an avocado or something equally healthy. Not that it matters now. And I don’t see the bar faucet, which I’d had to special order, but I don’t suppose that matters now, either.

And there’s something else different, but for the life of me I can’t think what.

The detective is waiting to hear why I should have known. Because things were going too well. Because it was a gorgeous September morning and the sun was shining. And, most important, because Elise was loving how the kitchen I was redecorating for her was turning out. So, I ask you—how could I not have known that something dreadful was going to happen? Still, even if I had sensed disaster looming, I’d have thought leak, crack, incorrect measurement—not murder.

“Well, because I’m a worrier,” I explain to the patient Detective Nelson, whose eyes keep straying over to Elise. She really did have a great figure for someone in her forties. Better than mine will be when I get there, which is sooner than I want to think about. I concentrate on the detective and let him concentrate on Elise’s body. “And this just proves that if you don’t worry about a particular thing, that’s the one that’s bound to happen. Then you can spend the rest of your life worrying about what you’re not worrying about.”

Well, I’ve got his full attention now. He’s staring at me like it’s my marbles on the floor and not the bunch of pills I stepped on. He seems to be framing his next question carefully so as to prevent another babblefest, but it’s futile. When I’m upset I can’t help saying stupid things. As if to prove it, I shake my head and out comes a pronouncement that my mother has been right all these years and my ex-husband, once again, was wrong.

“How’s that?” he asks, apparently fascinated by the pull-out warming drawer in the center island, despite the fact that Elise is lying face up on the unsealed tile floor with pills and change scattered around her.

“See?” I say, pointing to the broom just inches from her hand. “A little housework can kill you.”

The police photographer looks up at me. He is taking pictures of every angle of the kitchen and of Elise. And of the dark red stain that is seeping into the floor.

And, except for Elise, it’s all very familiar, the red stains in the kitchen, the police, the questions…

“You seem pretty cavalier about all this,” the detective says.

“If you’d had this dream a few hundred times, you’d be cavalier, too,” I tell him. Ever since the thing last year with my soon-to-be-ex-husband, Rio, when he tried to drive me crazy and I sort of shot him, the police have been regular fixtures in my dreams. Rather than think about that black time in my life, I choose to imagine myself as Cinderella trying to scrub out those stains.

When Cinderella before she meets the prince is a step up, you know you’re in trouble.

“This is no dream, lady,” he says.

I take great comfort in the fact that he knows the script. “The detective always says that. And as soon as he does, I wake up.”

Only nothing happens.

I ask the detective to pinch me, which sometimes works in my the-police-are-coming-to-get-me-again dreams. It occurs to me that this guy doesn’t look a whit like Jerry Orbach, who is the usual detective in my dreams, nor, for that matter, like David Caruso, who is my dream detective. At any rate, he’s watching the fingerprinting guy and he ignores me.

So I pinch myself.

It hurts. And I’m still in Elise’s up-to-the-minute, high-tech-appliance-with-old-world-charm kitchen. And Elise is still dead.

“This isn’t a dream.”

I say it slowly, feeling as though I’m somehow under water and every movement is that much harder, every word that much more distorted. The photographer, now snapping close-ups of the blood patterns on the terra-cotta floor, is coming closer and closer to me. Gently, with a glance for permission from the detective, he pulls on the cuff of my white jeans, lifts my leg and takes a picture of the bottom of one of my brand-new driving moccasins.

I kick the shoe off and it goes flying toward a young female officer leaning over Elise. I shut my eyes tightly and hear an ear-piercing scream. I figure I’ve hit her with the shoe, but she isn’t the one screaming.

Things around me double and turn yellow like those old color photographs from the early ’50s. Blackness hovers. Someone pushes my head between my knees and rubs circles on the back of my white Banana Republic V-neck T—soft, slow, seductive circles. I tilt my head slightly and peer up to find someone who looks too good to be real. I figure his looks must be enhanced by either the angle or my weakened state.

“Keep your head down,” he says, crouching beside me, murmuring about how I’m going to be all right. “And close your eyes.”

To be perfectly honest, what the good-looking detective is doing to my back with his talented fingers is not helping me get my bearings. If anything, things seem even less real and almost…dare I think it with Elise lying dead? Delicious.

“So, here we all are in a kitchen again, Mrs. Gallo,” Detective Nelson announces, bringing me back to reality and making sure I know he was there the last time.

“It’s Bayer now,” I tell him. It’s a little awkward, me with one name, the kids with another, but it’s not as if their teachers don’t know the situation. Heck, anyone who picked up a copy of Newsday or turned on a TV learned the whole story last summer. His jaded look says he thinks I’ve already hooked up with a new jerk to replace the old one. “Teddi Bayer. I’ve gone back to my maiden name.”

Detective Number Two nods, but Nelson says, “A rose by any other name.”

Whatever that’s supposed to mean.

Detective Cliché adds something on the order of, “outta the frying pan, into the fire.” I assume he is referring to the gazillion times the cops have had to come and take my mother, June Bayer, to South Winds Psychiatric Center, her home away from home.

I just shrug, and then there is this awkward silence, which I break by saying aloud what I’m wondering—who would want to kill Elise Meyers?

“I just can’t imagine how anyone could murder someone as nice as Elise Meyers.” Isn’t it amazing how much nicer you think people are after they’re gone? Elise could be a real pain in the butt, but lying there on 12-by-12 tiles that she wasn’t so sure about but decided to trust me on…well, she looks almost angelic. That is, if you don’t count the hot-pink satin and black-lace getup she’s got on.

Nelson asks what makes me think it was murder while he casually places his card on the table by my arm. “Looks to me like the dog knocks the pills and stuff off the counter, she hears him, comes down and slips cleaning up the mess. Bang. Dead.”

I roll my eyes the way my twelve-year-old daughter does when she wants to ask how I can be so old and still so stupid but wouldn’t dare say it in so many words.

Detective Nelson catches the look and says something obnoxious, like Why don’t you give us your version, Sherlock? at which point Detective Number Two pulls out his card and places it on top of Nelson’s, as if he’s trumping it. Detective Andrew Scoones. And his isn’t wrinkled, either. His card, I mean.

“Well,” I say, brushing some wayward bangs out of my eyes so that I can see better. Maybe so I look better, too. “First off, Maggie May is a bichon frise and couldn’t reach the counter with a ladder. So tell me how she could have knocked anything off a work island three feet above her head. Second, the dog was out front when I got here, but only the backyard has an invisible fence, and it doesn’t look like Elise was taking her out for a walk, does it?”

Thinking about the details is easier than thinking about Elise lying dead on the floor.

“Since the tiles aren’t sealed yet, they aren’t slippery. And, on top of all that, the faucet is missing.” I’m on a roll now, imagining myself in a movie or on TV, and I continue. “In addition, since the alarm wasn’t going off when I got here, she must have disarmed it, which means she either knew the killer or didn’t care about his opinion, since her…uh…cellulite was showing.”

Everyone is staring at me. They are either incredibly impressed with my deductions or they figure I’ve gone nuts. Considering I’ve been down the latter road before and I’d recognize the signs (they always want you to sit down and stay calm, no matter what the situation is), I’m betting it’s the former.

“Just call me Mrs. Monk,” I say smugly. Of course, I miss the most important detail—the television character, Mrs. Monk, is dead, as Nelson quickly points out.

“So your theory is that someone broke into her house and killed her for her faucet?” Nelson asks. He pretends to be taking down what I say in a little notebook, but I don’t think he really is. “You get that, Drew?” he asks his partner, who actually is taking what appear to be copious notes.

“I’m saying that I left the faucet on the counter yesterday when I delivered the bar stools and that it’s not there now.”

The detectives exchange a look as though I’ve picked up on something they already know but I’m not supposed to.

I don’t bother mentioning my feeling that something else is not quite right in the kitchen because they are already acting like I’ve got a screw loose and because it seems as though something is more right than wrong.

I mean, if you don’t count Elise.

Detective Scoones puts on a new pair of rubber gloves and picks some of the pills off the floor to look at them. He lifts one off the little teddy Elise has on.

“Looks like she interrupted a robbery,” he says.

“Only, her ring’s still on,” I say, embarrassed that I checked while I waited for the police to show up, and pointedly not looking at Elise now because I don’t want to see them looking at a dead woman’s finger even though I did.

Detective Nelson suggests that maybe they just couldn’t get the ring off Elise’s finger.

I think about how she waved that diamond around like it was a medal, and I swear I can hear her voice in my head echoing Charlton Heston’s sentiments— “From my cold, dead hands.” Only I guess she wouldn’t let go even then.

Things aren’t adding up, but Detective Harold Nelson isn’t interested in my theories. And, truth be told, I’m not interested in Detective Nelson, so I direct my observations to Andrew Scoones, aka The Handsome Detective.

I tell him that, in addition to the ring, she’s got a Bvlgari watch worth about ten thousand dollars. They start to cover Elise’s body with a sheet and stop to look for the watch, which I already know isn’t there.

“You should check upstairs in her nightstand,” I say. Elise had been very specific about needing a small drawer beside her bed for “everyday” jewelry. If I had a ten thousand dollar watch, it a) wouldn’t be “everyday” jewelry, and b) would be kept in a safe. But then, I had a husband who would have stolen it and given it to one of his girlfriends and then accused me of losing it, like he did with the little diamond anniversary necklace he gave me. “She kept her watch in the top drawer on the left side of the bed.”

“You just happen to know which side of the bed she slept on?” Nelson asks, one eyebrow raised like this tidbit of information actually proves his theory that I’m the killer and I’ve just hoisted myself by my own petard. A little slow on the uptake, it finally occurs to me that they know damn well that this is a murder. They are simply toying with me to see what they can get.

“There anything else you want us to check out on this murder theory?” he asks, as though the fact that I’m an interior designer means I couldn’t possibly have anything valuable to offer beyond what color to paint a focal wall.

They suggest I leave the house for a breath of fresh air and Detective Scoones, Drew, instructs an officer to accompany me. When I ask if I can go home, he tells me he’d like me to stick around.

Meanwhile, Detective Nelson tells one of the uniformed cops to check upstairs. When the cop reminds him they already have, Nelson tells him to check again, thoroughly. The thought that the murderer might still be there hadn’t occurred to me, and that—combined with the blood on my shoe—leaves me weak-kneed all over again.

Or maybe it’s the idea that the good-looking Detective Drew wants me to hang around. Funny how your brain (or is it just mine?) can operate on two levels at the same time. Like when your great-aunt in NYC dies and for just a split second you wonder if her rent-controlled apartment can pass to you. I mean, you’re sad and all, but there’s this little section of your brain, this piece that sentiment and emotion doesn’t touch….

Never mind. I’m sure it’s just me.

As an officer escorts me toward the door, limping because I am down to one of my good Todd’s driving moccasins that I’ll probably never find on sale again, it occurs to me that maybe the reason I can’t leave is because I’m a suspect. “They can’t possibly think I could have killed Elise, right?” I ask as he opens the front door for me. He looks me over. My working wardrobe consists of only black, white and beige, so that I never clash with swatches I’m showing a customer. Today I am wearing white jeans from T.J. Maxx’s clearance rack with some designer’s name on the back pocket. They’re a size ten, but they run small, and I look pretty good. I mean, for me.

“I wouldn’t think so,” the patrolman says. “No blood. If you hit that woman, you’d be pretty spattered in blood.”

I stiffen, holding my arms away from my clothing. Suddenly I don’t know what to do with my hands. My body seems alien to me—a piece of evidence. Even though they don’t have Elise’s blood on them, I will have to throw out the clothing I have on because every time I even glimpse them in my closet I will remember that I was wearing them when I found Elise.

Outside, four police cars are parked at odd angles to the curb, and neighbors are beginning to cluster at the ends of driveways. Two women in jogging suits round the corner and stop in their tracks to stare at me. They converse with each other in hushed tones and then take off in the other direction. It is eerily quiet and I think about how different this neighborhood is from my own.

I am in a foreign country, or maybe on another planet.

In my world the residents would be all over the police, demanding to know what happened. There would be a lot of yelling, and every sentence would have either “Syosset” or “this community” in it, driving home what the police already know—that we don’t tolerate bad things happening in our neighborhood. Someone, probably Joan Favata, would be marshaling her daughters to take all the littler kids around the corner to Mrs. Kroll’s place where they could play on the new swing set, and someone else would be pushing money at the older ones to stroll down to Carvel for soft ice cream so that no one would see something awful come out of the house, like a body bag.

Here in The Estates, there appear to be no children. There isn’t a single basketball hoop in anyone’s driveway, no bikes litter the road. There isn’t a single Sesame Street Plastic Playhouse or so much as a doll stroller blocking the sidewalks. A lone woman in a midcalf skirt and man-tailored blouse with a Ralph Lauren–ad dog leaves a nouveau Victorian with a wraparound porch that’s a shade too small for the wicker furniture on it. She throws a fisherman’s knit sweater over her shoulders as she casually saunters by the patrol car. Striking a pose, she stops to talk to one of the patrolmen while signaling her dog to stay off Elise’s perfectly manicured lawn and sit beside her. The cop pats the dog and appears noncommittal as the woman gestures toward first Elise’s house and then her own.

Across the street a man has the hood of his Mercedes up, pretending to look at the motor. He waits for the woman to leave Elise’s driveway and meets her in the street, where they both rub their arms to ward off the fall chill and glare suspiciously at the cop and at me.

The gardeners across the street start putting their tools in their trucks, but they are asked to stay put until they are released by the police. They begin to argue—they have other leaves to blow, this is no business of theirs, and the neighbors begin to demand to know what’s going on. The policeman guarding me, if that is what he is doing, goes into the street to calm everyone down, but his presence seems to do the opposite.

And then, with the exception of a gasp or two, all sound stops abruptly when a car marked Medical Examiner pulls up to the curb.

I reach into my handbag and fish around for my cell to call Bobbie Lyons, my business partner/neighbor/best friend. When I turn on the phone there are several messages waiting for me. The officer returns to me, probably to tell me I’m only allowed one call, and I show him that two of the messages are from Elise.

“Do you think it’s okay for me to hear them?” I ask, thinking that I don’t really want to hear Elise’s voice from the other world and realizing that maybe in her moment of need she was calling me for help.

The officer, I suppose thinking the same thing, tells me to wait and ducks inside the house.

The crowd, which had turned into one of those living tableaus, comes to life and closes in. Before I can answer any of their questions, a strong arm yanks me back into the house.

“Whatcha got?” Drew asks me. His partner is nearby, examining some of the sports memorabilia that I’ve creatively placed in the hallway I expanded to accommodate it. A sort of Hall of Fame, if you will, which allowed me to move the stuff out of the living room to please Elise and still keep it in plain sight to please her husband. I hand Drew my phone and tell him which keys to press. He gives me a look that says he didn’t make detective being stupid, and I back away from the phone.

I am still close enough to hear Elise’s excited voice as she tells me how much she loves the new look. Do I think she should reconsider my suggestion that we do the back wall in deep Chinese Red? She’s thinking that the new, mustard-color upholstered bar stools would look great against the red, just as I told her they would. Look, we hear her say (my head is now inches from The Handsome Detective’s and I notice he smells good, too).

I press the button that lets us see the picture Elise has sent. I touch the screen lovingly. Yes, Elise, the wall would have looked perfect in a vintage claret wallpaper with a small golden-mustard accent design. And the bar stools, as I can see in the picture, actually looked better where I placed them than where they are now.

Drew says they’ll need to confiscate the phone and bring it down to the lab to examine the picture for any possible clues—which I totally understand. I mean, Bobbie’s sister Diane is a rookie cop and she’s always reporting that they confiscated this or that.

On the other hand—and I don’t want to seem petty here—this is my phone, my link to the outside world, my security blanket. I tell him we can just send the photo to the precinct via e-mail. Nelson says he’s already got Elise’s phone and sees that the picture is saved in there. Just as I ask if I can have my phone back, there is a commotion outside and Jack Meyers, Elise’s hot-shot sports agent husband, pushes his way in.

All my nasty thoughts about how he doesn’t know “jack” about decorating evaporate as his face goes gray and he tries to grasp what the police are telling him.

He keeps asking what they mean by dead, as if there are different types or degrees. Probably like he thinks there are different degrees of fidelity or marriage. “Hit on the head,” he repeats over and over again. “A blow to the head.”

“It appears that way,” Nelson tells him. “We won’t know for sure until we see the autopsy report.”

If there’s a color grayer than gray, Jack turns it. I force myself to forget what I know about him and guide him to the “Martin Crane” chair in the living room, the one he refused to let me recover, never mind replace, and I help him sit. I open the antique armoire I’ve had retrofitted to accommodate a bar and pour him a straight Scotch.

After a healthy belt, he collects himself and tells us all how he wasn’t home last night because he was out fishing on his boat with a client and they got caught in rough seas and had to spend the night in Connecticut. Now, Jack’s a very successful agent and I know he hooks his share of big fish, but I’m willing to bet he doesn’t do it with a rod and a reel from his boat. Considering that most of his clients are women athletes, I’ll concede a rod, but not a reel.

At any rate, all of us know it’s a fish tale, but wouldn’t you know that Nelson takes down all his details, which are sketchy at best. He’s so awed by Jack’s circle that he just nods when Jack, with a nervous glance at me, assures him he’ll have the office call with the client’s number later.

As Drew is walking me out, I hear Jack tell Nelson he won’t consent to an autopsy. He says it’s against his religion. I have the utmost respect for religion and religious traditions, but how religious could he be with no mezuzah on the door frame? I kind of tap the doorjam where the little prayer holder ought to be, but, not being Jewish, Drew probably misses my subtle hint. I don’t believe that Jack doesn’t want that autopsy on religious grounds. I think he’s hiding something, or wants to, and I’m suspicious.

Oh, hell, let’s face it. I’m suspicious of every husband, and Jack’s no prize. Still, that doesn’t make him a murderer, does it?

Alone in my car I carefully back out, listening to my own breathing, and I realize that Elise will never breathe again. In my chest I feel my heart lub-dubbing. My blood is pounding relentlessly in my veins. A headache has settled into my left temple and my ankle itches where my jeans tease it. It seems I am taking inventory of everything that makes me alive.

Halfway down the street I realize I can’t see through my tears and I pull over. The thing that bothers me most about Elise’s murder—beyond the obvious—is that it happened in her own home. I don’t know about you, but if I ever get murdered I want it to be in some dark alley that I should have known better than to go into in the first place. Home is where you are supposed to be safe. And I wouldn’t want to get murdered there.

I wipe my cheeks with my bare arm but the tears continue to stream down my face. I think about calling Bobbie, but I don’t know what I expect her to do. I don’t want to talk. I just want to crawl under the covers and cry.

If only I hadn’t used up all my Go Back To Bed Free cards last year….