Читать книгу Sleet - Stig Dagerman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Translator’s Note

ОглавлениеWhile covering postwar Germany as a foreign correspondent for the Swedish newspaper Expressen in the fall of 1946, Stig Dagerman was advised by a fellow correspondent in the Allied Press Corps “with the best of intentions and for the sake of objectivity to read German newspapers instead of looking at German dwellings or sniffing in German cooking-pots.” The implicit criticism stemmed from Dagerman’s ambition to chronicle the supposedly “indescribable” realities of life for ordinary Germans in a land left in ruins at a time when world sympathies for the German people were at an all-time low and the need to judge and punish the guilty was at an all-time high, when the Press Corps and all the world were focused on the drama and expiation of the Nuremburg war crimes trials.

Dagerman sought instead to chronicle as nakedly as possible the suffering of all the remaining victims of the war and its ravages with an eye unaffected by the collective need to assign guilt for the atrocities of a horrendous Nazi Regime. What followed were a series of articles, later collected in the book German Autumn, that examined the very nature of human suffering and the moral complexities of justice.

As he came to understand just how much his own motivations were at odds with those of the international press corps, Dagerman wrote in frustration to fellow Swedish writer Karl Werner Aspenström in the midst of his assignment in Germany:

A journalist I have not yet become, and it doesn’t look as if I’ll ever be one. I have no wish to acquire all the deplorable attributes that go to make up a perfect journalist. I find it hard to meet the people I meet at the Allied Press hotel – they think that a small hunger-strike is more interesting than the hunger of multitudes. While hunger-riots are sensational, hunger itself is not sensational, and what poverty-stricken and bitter people here think becomes interesting only when poverty and bitterness break out in a catastrophe. Journalism is the art of coming too late as early as possible. I’ll never master that.

If journalism was the art of coming too late as early as possible, then in short fiction Dagerman sought its antithesis, the art of coming in time. In his focus on fragile human subjects, particularly young people swept up in or swept aside by circumstances and forces much greater than themselves, Dagerman sought to trigger links of identification and empathy that could give his readers an understanding of the tragedies of human suffering before they became faits accomplis.

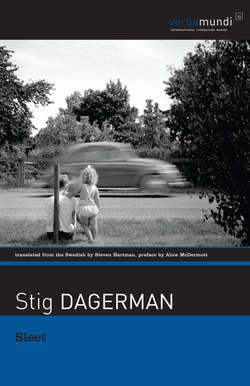

His classic short story “To Kill a Child” is a fine example. For a meager fee of seventy-five kronor Dagerman was commissioned by the National Society for Road Safety to write a cautionary tale as part of a campaign designed to get Swedish motorists to slow down on highways when speeding was becoming an increasingly difficult social issue with serious consequences for public safety.

What could have been an ephemeral and gimmicky work of public service fiction became perhaps the greatest short short story in the history of Swedish letters, for in this tale Dagerman took the simple redressing of a particular social problem as the starting point rather than as an end in itself and out of these mundane materials created a poignant tale of choice, chance, and human loss that rises to the highest levels of art, literary balance, and philosophical concision.

What makes this particular story gripping, like so many of Dagerman’s tales, is his earnest investment in short fiction as a vehicle of moral agency and insight, with a capacity to generate human empathy, identification, and understanding – a commitment, in short, to the art of coming in time.

STEVEN HARTMAN

Stockholm, Sweden September 4, 2012