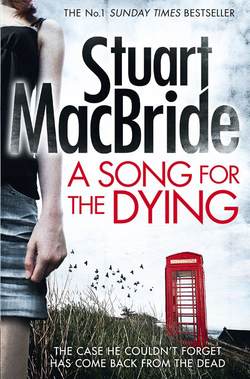

Читать книгу A Song for the Dying - Stuart MacBride - Страница 25

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

13

ОглавлениеAlice looked back over her shoulder as I pulled into Slater Crescent. ‘Are you sure it’s OK to leave Professor Huntly there, I mean what if he upsets all the—’

‘He’s a grown man.’ And besides, maybe getting punched on the nose by one of the Scenes Examination Branch would take the edge off him a bit. If we were lucky.

The Suzuki jerked and juddered as my right foot slipped off the accelerator. Bloody idiot. Oh, no I’ll drive this time. It’s been far too long. Need the practice…

Need my sodding head examined, more like.

Teeth gritted, I put the aching foot back down, on the brake this time. Eased Alice’s car up to the kerb. Killed the engine. Folded forward and rested my forehead on the steering wheel. Hissed out a breath.

‘Ash? Are you OK?’

‘Fine. Perfect. Never better.’ God that hurt. ‘Just … been a while.’

I straightened up, dug a pack of paracetamol from my jacket and dry-swallowed three of them. Pulled in a few deep breaths. Then opened the driver’s door. ‘I’ll only be a couple of minutes.’

She stared at me. ‘And he’s an old friend.’

‘It’ll be fine.’ I grabbed my cane and struggled out of the car. Closed the door.

Slater Crescent curled away down Blackwall Hill, giving the road a decent view across the valley to the Wynd. Over there, the sandstone terraces were arrayed like soldiers on parade. Expensive houses surrounding little private parks. Picturesque and historical beneath the heavy grey sky.

And a lot prettier than the seventies maze of cul-de-sacs and dead ends that surrounded us. Blackwall Hill: a twisting nest of grey-harled bungalows and terracotta pantiles. Gardens jealously guarded behind leylandii battlements. Knee-high wrought-iron gates with nameplates bolted to them: ‘DUNROAMIN’, ‘LINDISFARNE’, ‘SUNNYSIDE’ and half a dozen variations on ‘ROSE’, ‘FOREST’, and ‘VIEW’.

Number thirteen – the address I’d got from the mysterious Alec – had an archway of honeysuckle wound up and over a stupid little gate, like brittle strands of beige barbed wire. The nameplate had ‘VAJRASANA’ on it, picked out in gold letters. Gravel made a twisting path through bushes and dead flowers, seedheads heavy and drooping on either side. A concrete Buddha sat beside the path, his grey skin speckled with lichen.

A little girl knelt before him, trundling a bright yellow Tonka tipper truck back and forwards, scooping up gravel and dumping it at the Buddha’s feet. Making the beep-beep-beep noises every time the tipper reversed for another load.

I creaked the gate open and limped in, clanging it shut behind me with my cane. Pulled on a smile. ‘Hi, is your daddy in?’

She jumped to her feet, clutching the Tonka against her stomach. Can’t have been more than five or six, but she had a single thick eyebrow stretching across a mealie-pudding face. She smiled, showing off a hole where the two bottom middle teeth should have been. ‘Yeth.’

‘Can you run and get him for me?’

A nod. ‘But you have to look after my tiger for me.’ She pointed at an empty patch of grass, then lowered her voice to a whisper. ‘He’th thcared of clownth.’

‘OK, if any clowns come along, I’ll keep him safe.’

‘Promith?’

‘Course I do.’

‘OK.’ She patted a hand up and down, in mid-air. ‘You be good Mithter Thtripey, and don’t eat the man.’ And then she was off, skipping up the path and into the house.

I limped over and rested against the Buddha’s concrete head.

She was back two minutes later, dragging a small middle-aged man by the hand: dumpy, central parting, chinos and a cardigan. He fiddled a pair of glasses from his pocket and slipped them on. Blinked at me. Then beamed. ‘Ah, you must be Mr Smith. How nice to see you, Mr Smith.’ He turned to the little girl. ‘Sweetie, why don’t you take Mr Stripy through to the back garden so I can talk to Mr Smith?’

She stared at him, face hard and serious. ‘Are there any clownth?’

‘They all ran away when they heard Mr Smith was coming over.’

A nod, then she wrapped an arm around thin air and pulled it towards the side of the house. ‘Come on, Mithter Thtripey…’

The man watched her go, head on one side, a wide smile on his face. Then sighed. Turned back to me. ‘Now then, Mr Smith, Alec believes you’re looking for some spiritual guidance?’

‘Where is he?’

He placed a hand against his chest and gave a small bow. ‘This one has the questionable honour of being Alec.’

‘OK…’ Shifty was right, the man was a nutter. ‘In that case: semi-automatic, clean, at least thirteen in the clip, and a box of brass. Hollowpoint if you’ve got it.’

‘Hmm, that’s a lot of spiritual enlightenment.’ He joined me at the Buddha, leaning back against the statue. ‘Tell me, Mr Smith, have you truly contemplated the consequences of your actions here today? Because Karma is watching, and it’s never too late to change one’s path.’

‘Have you got it, or don’t you?’

He placed both hands against his chest, fingertips spread. ‘Take Alec for example. Accepting the Buddha into his life made a world of difference to Alec. Alec was a sinner – it’s true – and his life was hard and dark… Well, until Alec had his little incident and decided to let the teachings of the Buddha into his cold, cold heart.’

I pushed off the statue and stood, resting most of my weight on the cane. ‘You’re going to have another “little incident” if you don’t make with a gun in the next fifteen seconds. And it better be clean – I find out it’s been used in a hit, or a Post Office job, or some sectarian drive-by shite, I’m going to come back and introduce you to your god personally.’