Читать книгу It's Good Weather for Fudge - Sue Brannan Walker - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“Now some explanation is due for all this behavior. The time has come to speak about love.”

Carson McCullers, The Ballad of the Sad Café

“Nobody gets anywhere without love.”

Sue Walker, “It’s Good Weather for Fudge”

Carlos Dews

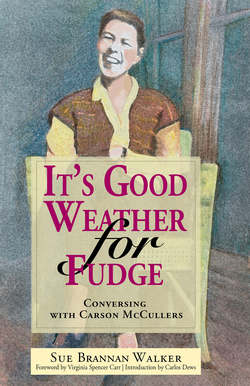

“It’s Good Weather for Fudge: Conversing with Carson McCullers”—a tender, intimate, and insightful imagined conversation between the most sensitive of novelists and the most perceptive of poets—is, quite simply, an expression of love. McCullers’s work as a writer was a vocation of the heart, an exploration of love and loneliness, motivated by her desire to have her boundless love returned. In recognition of her unceasing quest, a 1990s BBC Radio documentary on McCullers’s life and work was titled simply Love Me! Love, even if fleeting or sometimes imagined, was the balm that provided relief from McCullers’s experience of profound loneliness. McCullers’s oeuvre itself is a sustained call for love, understanding, and empathy. Sue Walker’s composition of “It’s Good Weather for Fudge” is an act of love, a response to the call issued by McCullers’s work.

The heart indeed is a lonely hunter, but, as Walker’s poem demonstrates, the hunt is made less lonely when there is hope of eventual success and by the knowledge that the world is populated by similarly lonely hunters. “It’s Good Weather for Fudge,” as a poem, is the purest form of response to McCullers. Sue Walker’s intimate conversation with McCullers allows her to respond to the implicit questions posed to the world by McCullers’s work: Do you love me? Will you love me? Can you love me?

In “It’s Good Weather for Fudge,” Walker revisits the milestones of her own life, makes profound personal links between those moments and McCullers’s life and the lives of her fictional characters, and weaves a tapestry of autobiographical and literary critical associations. Walker asks readers of the poem, as McCullers asked her readers, to join in a very personal conversation on love and to explore their own individual experiences of loneliness.

“Not to belong to a ‘we’ makes you too lonesome. Until this afternoon I didn’t have a ‘we,’ but now after seeing Janice and Jarvis I suddenly realize something. . . . I know that the bride and my brother are the ‘we’ of me. . . . I love the two of them so much and we belong to be together. I love the two of them so much because they are the we of me.”

Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding

Rarely do literary scholars, especially those such as myself who dedicate their careers to the study of a single author, speak frankly about our personal connections with or our feelings about our subjects. We rely instead on supposed objectivity to shield us from accusations of letting emotions influence what are supposed to be our dispassionate considerations of the work and lives we study. But literary scholars almost always have strong emotional justifications for the selections of their subjects. How else could we sustain the energy, engagement, and passion required to pursue our work, for decades, on a single subject?

I have dedicated my entire professional life primarily to research on the life and work of Carson McCullers without having ever confessed in print to the very personal—dare I say, loving—relationship I have with McCullers. My own empathy for McCullers and her characters motivates my interest in her and my desire to champion her as a writer. And so I consider literary scholars like Sue Walker who are also skilled poets to be most fortunate. Their art grants them the freedom to speak from the heart without the scholar’s blush. Sue Walker’s “It’s Good Weather for Fudge” gives me the courage to admit to my emotional response to McCullers.

“Often the beloved is only a stimulus for all the stored-up love which has lain quiet within the lover for a long time hitherto.”

Carson McCullers, The Ballad of the Sad Café

In an essay about Isak Dinesen published in Saturday Review in 1963, McCullers wrote about her first experience reading Out of Africa. She had heard about the book during a weekend visit with friends in Charleston, South Carolina:

All during the weekend there were references to Out of Africa. On Sunday, when I was leaving, they very quietly put Out of Africa in my lap, without words. My husband was driving so I was free to read. . . . We started driving in the early afternoon and I was so dazed by the poetry and truth of this great book, that when night came I continued reading Out of Africa with a flashlight. At the end of the book . . . I knew that sublime security that a great, great writer can give to a reader. With her simplicity and “unequalled nobility” I realized that this was one of the most radiant books of my life.

. . . Because of Out of Africa, I loved Isak Dinesen. . . . I had read Out of Africa . . . with so much love that the author had become my imaginary friend. Although I never wrote to her or sought to meet her, she was there in her stillness, her serenity, and her great wisdom to comfort me. In this book, shining with her humanity, . . . her people became my people and her landscape my landscape.

My initial response to reading McCullers was not unlike McCullers’s first reading of Dinesen. I encountered McCullers when I was an undergraduate at the University of Texas in the early 1980s. I recall telling a friend that I felt McCullers had somehow anticipated my own life, especially adolescence, and written her work, in advance, for me to experience when the time was right. Reading her was a sort of literary déjà vu. I felt a common sense of experience—growing up queer in the South, feeling from my earliest moments of consciousness a sense of isolation from those around me, a sense of antipathy to the place I was born, a desire for something greater than myself that I first found via music then via literature, and perhaps strongest of all, a profound sense of loneliness. I recall the strength of my identification with McCullers herself and the characters she had created. Thus began what has been a passionate desire to explore her work and thus my own psyche.

Reading Sue Walker’s “It’s Good Weather for Fudge” was/is an emotional experience for me, as was/is Walker’s reading of McCullers. Walker’s poem not only augments my personal feelings for McCullers and her work, but it also provokes a new response of association to Walker’s life and work. I recognize myself, again, in McCullers’s work and see myself reflected in Walker’s life as well. We—Sue, Carson, and I—are part of a nexus of identification, association, and love. We are “imaginary friends,” as McCullers wrote of her literary relationship with Dinesen. I like to think that McCullers was comforted by the idea that her readers might respond with love, or at least empathy, to her work. And I know that Sue and I have responded with love and recognition to this notion and in turn have felt comforted by it.

“The places of our childhood mold who we are and stick in our memories as if we had a glue pot and had pasted them inside the scrapbook of our brains.”

Sue Walker, “It’s Good Weather for Fudge”

I feel a similar sense of associative identification when I read “It’s Good Weather for Fudge.” My identification with McCullers and Walker has an address, a religion, and a soundtrack. The connection is explained in part by the particulars of the South in which we three grew up, and part of it is explained by the universal experience of loneliness. I feel a wonderful and frightening similarity in McCullers’s experience of her hometown of Columbus, Georgia; Sue Walker’s experience growing up in Foley, Alabama: and my own experience growing up in Garrison, Texas, in the most Southern-identified part of Texas. Although Carson and I fled the South, “the South is where [our] bones belong,” as Sue writes in her poem.