Читать книгу The Atlas of California - Suresh K. Lodha - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

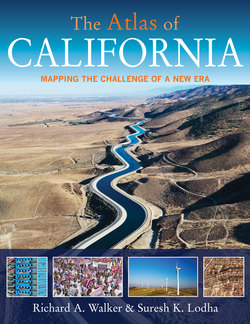

ОглавлениеCalifornia is just a sliver of the globe, a slice off the west coast of North America, one state among many United States; but it is more, much more. California is a world apart, a region unto itself, a state within a state, a place with its own character. New York, Washington DC, and Texas all feel very far away in outlook and obsessions. If, as a famous coffee company’s slogan has it, “geography is a flavor”, then California is one of the most distinctive and full-bodied. To draw up an atlas of California requires considerable imagination. It is a hard state to get one’s head—and compass—around. This is about more than its slightly crooked torso and varied landforms. It is about more than geographic subregions that so shape the life and outlook of residents, dividing Northern and Southern Californians at the Tehachapis, urbanites west of the Coast Ranges from farmers in the interior, or rainforest dwellers on the North Coast from desert denizens by the Salton Sea. It is about the way human history is deeply imprinted on the landscape in the form of gargantuan cities climbing the foothills of the San Gabriels, mines and tailings in the Sierra foothills, and farms stretching for miles across the Imperial Valley. The human geography of California is sometimes plainly evident, as in roads and skyscrapers, but sometimes obscure, like the toil of farmworkers or the quality of schools. A critical task of an atlas such as this is to make visible key facets of the human landscape of this great state. Because it is a place apart, California is rife with myths. One of the most persistent is that it is “The Coast”, a place of hippies and stars, not to be taken too seriously; yet what happens here is of crucial importance to the country, and sometimes the world. One reason is that California is not the mythic land of sun and surf, a place of leisure, but a center of industry, technology, and work. As a result, it is not the afterthought of the manufacturing Midwest or the New South, but the principal motor of the American economy. Another persistent myth is that people come to California for its balmy climate and decide to stay, rather than be drawn by jobs on offer by that economy, by the desire to rejoin distant friends and families, or by the need to escape dangers at home. Californians’ favorite origin myths dwell on the misty realms of the past. In Northern California, pride of place is held by the legend of the Gold Rush, with the hardy pioneers of 1849 facing adversity but finding gold aplenty (carried away by picturesque Wells Fargo stagecoaches). From this comes the moniker, The Golden State. Even though the easy gold ran out quickly, the Gold Rush is still seen recapitulated in every boom time from Comstock Silver to Silicon Valley. The Southern California origin myth is different, since the Gold Rush barely touched the region. Instead, the tale oft told is that of the civilizing role of the Spanish Missions, which enter the state from the south. The Mission Dream is embodied in plays and movies, but especially in the colonial revival architecture of the early 20th century which embellishes cities from Santa Barbara to Riverside. Astonishing as it may seem, California school children still have their impressionable heads filled up with these “just-so” stories in the required year of state history doled out in the 4th grade. Worse, they are likely never to get another lesson about what transpired after those founding moments of modern California—let alone what might be just plain wrong with these idyllic pictures of the state’s history. The most popular myth of all is undoubtedly the California Dream, which means anything and everything that people might imagine about their futures—and hence nothing solid at all. It is invoked to explain everything from farm settlement to postwar suburbs. Californians have had many dreams, and some have come true; but the real question is why dreams succeed or why they fail. If the California Dream has a germ of truth, it must be based on political economic realities, not merely the fantasies of literature, cinema, or theater.

Introduction