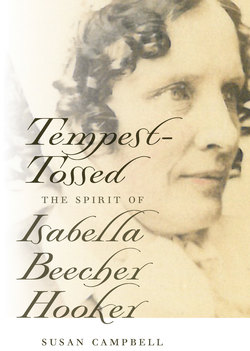

Читать книгу Tempest-Tossed - Susan Campbell - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

ISABELLA MARRIES, AND FACES A CONUNDRUM

And here we pause to ponder all the women through all the years who have questioned the role of marriage in society, and wondered if the institution was quite for them.

Can you blame Isabella, really, for hesitating to take that fine Beecher brain into a legal contract — the last one she’d ever sign — that to her was little more than a type of serfdom? The laws and her religion dictated that she demurely bow her head in front of a minister, perhaps make one last wave to her friends, and disappear into the home of her husband.

Isabella reached womanhood at a time when the male sphere — the “impersonal, immoral and uncertain”— had been sharply separated from the female sphere — the “personal, pure, and circumscribed.”1 As workers moved away from farms and into more industrialized pursuits, families began to mimic the Beechers in their frequent moves in search of better opportunities. This often strained or severed ties that once bound extended families, and the resulting isolation placed the responsibility for child-rearing squarely on the shoulders of families of origin — more specifically, on the mothers. More than ever, women were encouraged to forge intense relationships with their children for the betterment of the child — but not necessarily the mother, whose well-being was to take a backseat while she created good male citizens and prepared her daughters to do the same.2

Middle-class women were encouraged to keep mother-diaries by cultural arbiters like John S. C. Abbott, who insisted such journals would help women stay focused, remain aware, and would encourage rigorous review.3 Abbott was a writer and minister, and in his seminal 1835 work, The Mother at Home, he stressed the importance of daily asking oneself questions such as “Have I this day fulfilled all my duties toward God, my Creator, and prayed to Him with fervor and affection?”4

Avoiding his advice, wrote Abbott, could yield awful results. “Many an anxious mother has committed errors to the serious injury of her children, which she might have avoided had she consulted the sources of information which are within reach of all,” he wrote.5 In his proclivity for giving advice on how to achieve domestic bliss, Abbott rivaled Catharine Beecher, and Isabella paid close attention, lacking as she did a working example from her own mother.

The matter of John Hooker’s livelihood remained unsettled. His decision would have a huge effect on his family’s future earnings and social standing. Could he be allowed to make his own choice, or did the awesome righteousness of the Beecher clan deserve to hold sway? In a letter to her aunt Esther Beecher dated January 1, 1840, Isabella showed early signs of standing against her family’s considerable sway. She wrote that she did not want to influence her husband in his choice of careers. Yet in two letters that same month, she wrote John congratulating him on his choice of the cloth and then, later, wrote that she was prepared to be a reverend’s wife. It was no small thing to run counter to her family’s wishes.

And then Mary Perkins again weighed in with a January 1840 letter to John Hooker, written when she heard he’d decided to attend Yale’s divinity school:

Your decision did not surprise me, and I was prepared for it — tho’ I regret it, I certainly shall not suffer myself to be made unhappy by it. You and Isabella had a perfect right to decide for yourselves and I had no right to do anything but state my views and feelings on the subject, this I felt I ought to do, and have done so fully, I am perfectly satisfied you should do as duty and inclination prompt…. I shall hope to see you in the spring when we can talk over these matters much more calmly and rationally.

Mary Perkins may have felt comfortable defying the family because she hadn’t felt much a part of it. In a December 1840 letter to Isabella, she wrote: “I never felt that Aunt H. or any of the family loved me very much & never tho’t they had much reason to do so, and however much I may have regretted it I never blamed them for it — so you see there is a sort of mutual distrust….”

As complicated as Beecher dynamics were, and as much as John Hooker appeared to want to stay in the good graces of his intended’s family, he was born to be a lawyer, and he quit divinity school after a month to return to his first love. “My whole taste,” he wrote in his autobiography, “ran toward the law.”6

On her birthday in February of the next year, 1841, Isabella wrote John that her father was bringing the family together in the summer and that an August wedding would be as good as any. In July, she wrote to John and encouraged him not to be nervous, that only friends would be at the ceremony. She also wrote that her brother Henry Ward would be at the service, and she reassured John that she knew herself and knew that she loved him. But in a June 1841 letter to John, she wrote that “the fearfully foreboding thoughts come over me so often” and that she suffered from “sudden unaccountable changes of feeling, revulsion, and at times almost despair.”

Does every bride despair before her wedding? Was it prenuptial jitters? Whatever the explanation, on August 5, 1841, Isabella married John. Standing with them were maid of honor Harriette Day and best man John Putnam, both of them friends of Isabella’s from Cincinnati.7 Isabella was nineteen, and immediately she would need to learn to settle into the upper middle class to which she’d become accustomed to living with the Perkins family, and whose status had so eluded her poor preacher father. The couple moved to John Hooker’s boyhood home in Farmington, where they would stay for twelve years. If she was for the first time in her life financially comfortable, Isabella was not about to settle comfortably into her new role. From her 1905 Connecticut magazine article:

My interest in the woman question began soon after my marriage when my husband, a patient young lawyer, waiting for business, invited me to bring my knitting-work to the office every day, where he would read to me from big law books, and in the evening I might read literature to him, as his eyes were so weak as to forbid his ever using them in the evening. For four years, we kept on this even tenor of our way, and to it I owe my interest in public affairs and a certain discipline of mind, since I never attended school or college after my 16th year.

She was stunned when she came across a passage from Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England that explained the legal disappearing act a woman made upon her marriage. In civil law, a man and woman were separate, and could be sued separately, wrote Blackstone. But though the law recognized husbands and wives as one person, Blackstone continued:

yet there are some instances in which she is separately considered; as inferior to him, and acting by his compulsion. And therefore all deeds executed, and acts done, by her, during her coverture, are void; except it be a fine, or the link matter of record…. She cannot by will devise lands to her husband, unless under special circumstances; for at the time of making it she is supposed to be under his coercion.8

The devil was in the footnotes, which the Hookers read aloud to one another. In this case, the footnotes said that a married woman’s ability to own property was severely limited and depended mostly on the graciousness of her husband. As the daughter of a poor minister, Isabella had no property, and from where she sat in her in-laws’ home in Farmington, she hadn’t the means of acquiring any. The thought that the law forbade her from ever doing so angered her a great deal.

From her Connecticut magazine article: “I shall never forget my consternation when we came to this passage: ‘By marriage the husband and wife are one person in law, that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage, or at least is incorporated and consolidated into that of the husband under whose wings, protection and cover, she performs everything.’”9

A few states had what were known as “women’s separate property acts,” or laws that allowed women to keep control over any property they brought into a marriage. Connecticut was not one of them. Defenders of Blackstone’s principles argued that “‘oneness’ was the core principle of happy marriage and virtuous public order.”10 Allowing women to own property would, went the argument, be the death of marriages everywhere.

Isabella’s earlier concerns about how she would exist in a traditional marriage resurfaced with a vengeance. The suspension of her “very being or legal existence” had been, precisely, her fear. If she no longer “existed”— except under the wing of her beloved husband — then she no longer existed. As great as her love for John Hooker might have been, suspension of herself was something she could not countenance. The couple discussed the phenomenon exhaustively until, wrote Isabella, “the subject was dropped as a hopeless mystery.”11

But it didn’t go away. The fear only sank below the surface while Isabella, attentive to the early instructions of sister Catharine, focused on her home life.

The next year, on September 30, the Hookers welcomed their first child, a boy they named Thomas, but he died of unknown causes before his first birthday.12 It was a bitter blow to them both. Isabella’s response was to turn her attention even more slavishly to her household, and, following the advice of John S. C. Abbott, she began a series of detailed journals that recorded what can only be called the most mundane of household tidbits — the choice of curtains in the bedrooms, the china setting, the subsequent children’s latest sayings — from the month the second child was born until shortly after the youngest child’s birth, a span of about ten years. Her motivation may have been partly grief, and partly older sister Catharine’s influence, whose writing about the “cult of domesticity” was felt particularly acutely by her younger sister.13 The pain of losing her first son moved Isabella to focus on what she perhaps thought she could control, even while that focus removed her from the broader world, the one she had glimpsed at her father’s table and during the early days of her marriage. Those hours once spent reading the law and discussing literature were now given over to running a well-to-do household and rearing children. The Hookers would have three after Thomas — Mary, born in 1845, Alice, born in 1847, and Edward (Ned), born a long — by the standards of the day — eight years later, in 1855. This span and their relatively small family of three children suggest that Isabella and John took some responsibility for controlling family size.14

By comparison, sister Harriet bore seven children — including twins — a family size about which Catharine, in a letter to Mary, bemoaned: “Poor thing, she bears up wonderfully well, and I hope will live through this first tug of matrimonial warfare, and then she says she will not have any more children, she knows for certain for one while.”15

Isabella’s letters to John — whose work often required him to travel — and to her family show an increasingly frustrated woman. That she loved her children is unquestioned; that she frequently feared how best to show that love and to rear them into responsible adults, equally so. Though in earlier years fathers were enjoined in sermons to rule their households and look after their children, by the time the Hookers were raising a family, the duties of child-rearing had shifted to the mother.16

Isabella with daughter Mary, 1848–49. Courtesy of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

If Isabella did not feel up to the task of raising her children, she had at her disposal a variety of mothers’ magazines spawned by local maternal associations intent on encouraging women to embrace their domesticity.17 Catharine, in fact, suggested that women should be forgiven for their mistakes in mothering, as they “have never had the knowledge which they have needed”— information she, never married and never a mother, was happy to dispense.18

How much Isabella relied on outside resources to teach her about mothering isn’t known, but without the example of an involved mother herself, Isabella found herself frequently relying on the idealized version of Mother — and frequently feeling as if she fell short. Her “maternal devotion and vigilance could only have intensified her fear that the world of events, before which she and John had once stood as ostensible equals, was gradually becoming closed to her — not by the fiat of her husband, but by the all-absorbing demands of hearth and home.”19 Her frustration may have manifested itself in an increase in physical complaints throughout the 1840s. In a January 1843 letter, she wrote John that she was considering homeopathy — which in Connecticut was a relatively new form of alternative medicine — for her general malaise.20 She apologized for her “nervous hypochondria” that was sometimes accompanied by unhappy dreams about her mother.21

Isabella with daughter Alice, 1848–50. Courtesy of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.