Читать книгу Our House is Definitely Not in Paris - Susan Cutsforth - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Baguettes, Bérets and the Eiffel Tower

ОглавлениеThe images that are redolent of France are baguettes, bérets and the Eiffel Tower. Even Parisians themselves say that they discover a new piece of enchantment every day in their magical city. Since the baguette forms the centerpiece of their daily culinary ritual, I am sure they flock immediately to the boulangerie each year that is awarded ‘Paris’ Best Baguette’ award. Participating bakers drop off deux baguette each. If their baguettes don’t conform to the strict guidelines, they are discarded. It is once again a demonstration of the artform that is French cuisine. A traditional baguette must be crunchy on the outside and fluffy on the inside. They are evaluated on a specific measurement, appearance, texture, smell and taste. A tell-tale sign that a baguette is commercially baked in a factory, rather than being an artisan creation, is the rows of dots underneath that are similar to Braille. The words ‘Artisan Boulangerie’, proudly displayed outside a boulangerie, is all you need to know in your quest for the perfect baguette anywhere in France.

The art of making baguettes is by no means a simple one. The intricate craft entails placing each one on a cloth and rolling it so they are all separated. They are all gently patted into place with a smooth paddle of wood covered in fine gauze. Each one is then scored with a knife. Even this ostensibly simple process is a step that distinguishes one< artisan baker from another, for all their scoring is an individual process and, therefore, an indelible mark of their craftsmanship. While it is a form of art, it is by no means as enduring as a Rodin sculpture. Day after day, the dedication of the artisan baker continues and all French people worship at the shrine of pain.

Creating a baguette for the esteemed award means that it will be judged by a formidable panel that consists of professional bakers, journalists, union representatives from various boulangeries, and prize-winning apprentices and previous winners. Winners even then supply their supreme baguettes for the following year to the Élysée Palace, the home of the French president. When President Sarkozy was in power, there was much speculation that Carla Bruni would most certainly not have succumbed to one of the most heavenly delights on earth.

Pascal Barillon has been awarded best Parisian baguette several times. This has ensured his boulangerie in Montmartre is one of the most popular in Paris. It comes as no surprise to learn that he produces a staggering 1500 a day. It is no wonder that bakers are awake long before the sun, to ensure their dough rises in time for petit déjeuner customers. Their ambition is to ensure that an artisan baguette has an uneven colour on the crunchy crust, and that inside the air holes are irregular.

For the first time in six years, the winner is not in Montmartre. Ridha Khadler, originally from Tunisia, has taken the award to the 14th arrondissement, Montparnasse. It is truly well-deserved, for he has been producing baguettes since 1976 and working from 3am until 9pm each day. The baguette is as symbolic of France as a French man’s béret. Dedication, devotion and craftsmanship are kneaded into every baguette by every artisan baker in France.

What are the other icons that are conjured up when your thoughts turn to France? Bérets, of course, and the Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower, on the Champ de Mars, was named after the engineer, Gustave Eiffel. His company designed and built the tower in 1889 to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. It was the entrance arch to the 1889 World’s Fair. The original idea was for the tower to be dismantled after a twenty-year period. However, it was so well-engineered that it was decided it would be left in place.

Its design was the source of criticism from some of France’s eminent artists and intellectuals. They viewed it as a gigantic black smokestack that marred the beauty of Paris. Gustave Eiffel, however, likened the tower to the pyramids of Egypt. So it is today that just as the pyramids are synonymous with Egypt, the Eiffel Tower represents all that is iconic about France.

Bérets are the image of all that is quintessentially French. They were first worn by shepherds in the 1800s in the Basque country. By the 1920s, bérets were commonly worn by the working classes, and not long after, more than twenty French factories began producing millions of bérets. They took on a new life when military bérets were first adopted by the French Chasseurs Alpins in 1889. They were then used by the newly formed Royal Tank Regiment during World War I, when it was realised they needed headgear that would stay on while climbing in and out of the small hatches of the tanks. The béret is now a significant fashion statement on the streets of Paris.

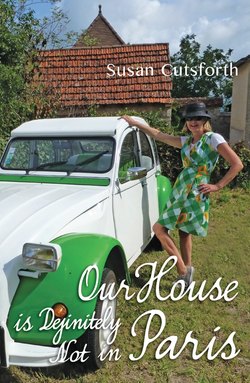

Today, there are only two producers of bérets remaining. It is still strongly symbolic in the south-west of France, where our petite maison is. It is worn to celebrate traditional events, like our own vide-grenier, when all the band members entertain everyone, eating déjeuner in Marinette’s orchard. The fact that I too was wearing a red béret, just like theirs, made me feel a part of Cuzance’s special annual celebration.

These are the evocative images that linger long after you return home; the enduring true-life metaphors that capture the essence of France. The twinkling lights of the Eiffel Tower, dominating the skyline of Paris as you wind your way through the film-set streets in the glowing embers of late evening. The Frenchmen in the markets, wearing timeless striped Breton shirts — introduced in 1858 by French law to locate fishermen who had gone overboard — their bérets tipped at a jaunty angle, a freshly baked baguette tucked under their arm.

Café scene, Paris

Lunch in Martel