Читать книгу I, Eliza Hamilton - Susan Holloway Scott - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

I attended that first assembly not with my aunt and uncle, but with a friend, Kitty Livingston. Kitty had persuaded (or more likely begged) her father to take a house in Morristown while the army was encamped there, even though their home of Liberty Hall was only twenty miles away in Elizabethtown. Kitty was only an acquaintance, but a distant cousin in the way of so many of us from New York, and I was delighted that she was in town for the winter, too.

That night we rode together with her parents in the second bench of their sleigh, our evening finery bundled beneath thick furs as we traveled across the wintery roads. We wore quilted silk petticoats beneath our gowns, and at our feet we each had a carved oak foot warmer filled with hot coals. The skies were overcast, and we all prayed the next snowstorm—for so it seemed inevitable that one would come—would hold until after the assembly. The sleigh’s lanterns cast their wavering light across the snow banks on either side, and the tiny brass bells on the team’s harnesses rang merrily in the cold night air.

Sharing my excitement, Kitty grinned at me, and snuggled a little closer both for warmth and in confidence. She was quick and lively and flirtatious in company, one of three sisters as was I, and always the first with fresh news from everyone and everywhere. I soon learned, however, that for the first time I was the center of tonight’s fresh gossip.

“So tell me, Eliza,” she said softly in a near whisper that her parents wouldn’t overhear, our conversation further shrouded by the fur-edged hoods of our cloaks. “How is it that all the talk in the town and the camp is of you and Colonel Hamilton?”

“Then this place must be tedious indeed, if that is the best talk it can muster,” I said, surprised. “Colonel Hamilton and I have supplied very little to your mill for tattle, Kitty.”

“I’ve heard otherwise,” she said. “In fact I’ve heard of little else.”

I frowned, my hands twisting uneasily inside my muff. I didn’t like being spoken of, especially since I suspected most of what was being said was embellished, if not outright tales. All I could do was hope to correct Kitty, a vain hope though it might be.

“Colonel Hamilton has called upon me at Dr. Campfield’s house in the evening,” I began, “and I’ve received him in the crowded company of my aunt and uncle as well as the Campfields. He has their approval, and my father considers him a worthy gentleman, too. Colonel Hamilton and I have walked together in the town, with my aunt ten paces behind us, and he and I have exchanged greetings in passing as he went about his duties near the headquarters. Oh, and he joined me at Sunday worship.”

“Sunday worship?” she repeated, her voice rising in teasing disbelief. “Hamilton? I vow he’s never seen the inside of a church, the wicked heathen.”

“He did come with me,” I insisted, “and it was by his own initiative, too. That’s all that’s happened between us, Kitty. There could hardly be anything less scandalous.”

I wasn’t exaggerating. Alexander’s regard toward me had been so decorous and proper that, in the telling, it must have sounded almost boring, and without even a flicker of scandal. Yes, there had been times when I’d felt sure he was going to kiss me, but at the last moment he’d held back: he was that intent on proving himself worthy of me.

And to be entirely honest, I rather wished he hadn’t. An honorable gentleman was all well and good, but if he’d shown me a bit—just a bit—of the rakish gallant that I sensed was within him, I wouldn’t have objected. I wanted him to kiss me, because I wanted very much to kiss him.

But clearly Kitty didn’t believe me, and smothered her laughter behind her gloved hand.

“Hardly less scandalous, Eliza,” she whispered, “and perhaps infinitely more. You can’t play the innocent with me, especially not when your dalliance is with Colonel Hamilton. Recall that he’s long been an acquaintance of mine, and that we have no secrets between us.”

“I assure you, there aren’t any secrets for him to share,” I protested, painfully aware of how she might indeed know more of him than I did. Kitty and Alexander had in fact been friends for years. When he had first arrived as a youth in our colonies from Nevis, he had attended Elizabethtown Academy in New Jersey, where he’d boarded with the Livingston family. To hear Kitty tell it (which of course she’d made sure I had), the schoolboy Alexander had been thoroughly moonstruck over her, yet she’d deftly turned his infatuation into a friendship.

“No secrets, no.” Kitty paused now for emphasis, her upper teeth pressing lightly into her lower lip in a way that was unique to her, as if biting back what she’d say next. “No secrets, because where you are concerned, Colonel Hamilton cannot keep them. He wears his heart like another medal pinned to his coat, there for anyone who wishes to see how the name Elizabeth is engraved upon it.”

“Hush, Kitty,” I said, uneasy with her overblown foolishness.

“Then let me tell you this, Eliza,” she said, leaning closer. “You know how the officers are in the habit of having supper together, and how after the cloth is drawn, they will sit for hours drinking and toasting until they tumble into their cups, and their menservants must come claim them.”

“What of it?” I said warily. Such behavior among gentlemen was hardly unknown to me; my father’s entertainments for his friends were often like this.

“What of it?” she repeated, unable to keep the triumph from her whisper. “Because I have it on the best advice that when the officers take their turns with a toast for each wife and sweetheart, our dear friend Hamilton raises his glass to you by name, and all the other gentlemen follow.”

I listened, stunned. Having my name toasted in the officers’ quarters would not please my aunt, but I found it undeniably thrilling to think that Alexander Hamilton would toast me as his sweetheart.

“You are sure of this?” I asked eagerly. “You know it for fact?”

“I wouldn’t tell you if it weren’t so,” she said. “We both know that Colonel Hamilton has left half the women in New Jersey panting for his attentions, yet you, Eliza, are the one who has dazzled him. Though it’s not surprising, is it? You’re a perfect match for a man like him. You’re a Schuyler, and you’re rich, and your father’s a friend of His Excellency’s, and—”

“Why must everyone assume that he likes me only because of Papa and his money?” I whispered, my frustration spilling over. “Your family has power and wealth, too, Kitty, and no one says that of you.”

Kitty gave a small, dismissive shrug to her shoulders that was also faintly pitying. “That’s because no suitor of mine has been as impoverished and without a respectable family as Colonel Hamilton.”

I don’t believe she intended to wound me or insult Alexander, but her words still stung.

“Colonel Hamilton possesses qualities and virtues that are worth far more than mere wealth,” I said warmly. “I value him for himself, not for his family or fortune.”

She nodded and fell silent, and remained silent so long that I feared I’d spoken too much. I was almost ready to apologize when she finally spoke again.

“Oh, Eliza,” she said softly. “You care for dear little Hamilton that much?”

“I do,” I said so quickly that I startled myself. Yet it was true; I couldn’t deny it, nor did I wish to.

“How fortunate you are!” she said wistfully. “How fortunate you are! I have yet to have such sentiments for any gentleman.”

“That can’t be true, Kitty, not of you.” Kitty was a belle, a beauty, and always surrounded by admirers at every ball and assembly in a way that they never had been for me.

By the glow of the sleigh’s lanterns, the edge of Kitty’s hood shadowed her face, and all I saw was her half smile, a smile that had lost all its earlier humor. Carefully she lifted her hood back over her shoulders, and the light twinkled in the paste stars she’d pinned into her elaborately dressed and powdered hair, all icy-white as if she were a snow queen incarnate. She turned, and now I could see the entirety of her face, and the concern in her eyes.

“You asked me earlier to speak plainly, and I shall,” she said, covering my hand with her own. “Take care of your heart, Eliza, and do not give it blindly. Perhaps I know Hamilton too well, and I know what he aspires to be. He is ambitious, and he is determined, and he won’t let anything or anyone stop him.”

“If you mean Alexander will achieve great things in his life, Kitty,” I said, “then we agree, as friends should.”

“Hamilton charms the world and makes friends with ease,” she said, “but he also makes enemies, and the higher he rises—and he will rise high—the more hazardous those enemies shall be to you both.”

“I don’t believe it, Kitty,” I said, the only proper answer to unwanted advice, and pulled away my hand. “None of it, not of Alexander.”

“Believe it or not, as it pleases you.” She glanced down at her muff, avoiding my gaze. “His character is widely known among the other officers, and many of the other ladies here, too. But if your father isn’t troubled by Hamilton’s flaws and faults, then why should you be?”

“Papa isn’t,” I said quickly. “Nor am I.”

“Then I’ll never speak of the matter again.” She darted forward and kissed me on the cheek, her lips cold. “Of all women I know, Eliza, I pray you’ll be happy, no matter which gentleman you marry. Now come, let’s dance, and break every heart we can.”

* * *

A dancing assembly held by subscription (I’d heard the extravagant sum to be $400 a gentleman, but that was at the inflated rate of our then-near-worthless paper bills) and supported by thirty-four of the most esteemed officers of our army sounds like a grand affair. For us wintering in Morristown, it was. But if I had heard described the conditions of this self-proclaimed assembly whilst still in Albany, I would have laughed aloud.

Instead of taking place in an inn or private residence of the first quality, this assembly was held in a military storehouse built by the army near the Morristown Green. Now emptied of goods, the storehouse was as full of echoes as a barn, and like most barns, it had been built for rough service, without any amenities or decoration; I would venture it to be seventy feet in length, and forty in breadth. A pair of crude cast-iron stoves stoked with wood were the sole sources of heat in this cavernous room, and lanterns for light had been strung along the walls on a length of rope. Both the stoves and the inferior tallow candles in the lanterns smoked, and even this early in the evening there was a haze gathered just below the ceiling beams.

The stables for my father’s horses in Albany were more elegantly appointed than this space, and yet the guests gathered here were as brilliant a company as any in our country. Most of the officers wore their dress uniforms, and the lanterns’ light glanced off gold bullion lace, polished brass buttons, and medals and other honors.

Of course, we ladies were not to be outdone, and our gowns were like bright silk flowers of every color. Our hair was powdered and dressed high on our heads, and ornamented with silk flowers, ribbons, paste jewels, and even a plume or two. To be so expensively and stylishly attired in the middle of a war might seem to some to be wrong, even disrespectful, but as Aunt Gertrude noted, our finery could be wonderfully cheering to the spirits of the gentlemen in the army, and proof to the British that we refused to be subdued. We ladies were also in the minority, with more than three times as many gentlemen in attendance; there’d be no wallflowers tonight, that was certain.

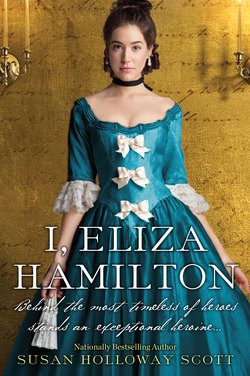

I’d chosen my own gown with care, a brilliant silk taffeta that was neither blue nor green but a shimmering combination of both, much like a peacock’s plumage. Being small in stature, I often wore vibrant colors so I wouldn’t be overlooked in company. The sleeves and bodice were close-fitting and the skirts very full over hoops, as was the fashion then, and the neckline was cut low over my breasts, with a thin edging of lace from my shift. Around my throat was a strand of glass pearls fastened with a large white silk bow, and earrings of glittering paste jewels hung from my ears, my mother having wisely decided that the encampment was no place for fine jewels. Unlike most of the ladies, from choice I wore no paint on my face. I suspected my cheeks were rosy enough without it because of the cold and the excitement, and I also suspected that Alexander would be like other gentlemen, and prefer me without it.

At least he might once I found him. I scanned the guests eagerly, searching for the one face I longed to see above all others, but in vain. The assembly’s subscribers stood in a line near the door to greet newcomers, and as I waited my turn I continued to look for Alexander. Other gentlemen appeared to ask me for dances and though I smiled, I turned them aside. Alexander was one of the subscribers, and he’d invited me as his guest. How could he not be here?

“Where’s Hamilton, I wonder?” Kitty murmured beside me. “He’s usually one of the earliest to arrive at these affairs.”

“He’ll be here,” I said swiftly, as much to reassure myself as to defend him. “I don’t doubt him.”

Kitty smiled slyly over the spreading arc of her fan. “He’d do well to appear soon, or else some other gentleman will scoop you up, especially in that gown.”

I didn’t smile, because I’d no wish to be scooped up by anyone other than Alexander. We’d almost come to the end of the line anyway, and to my surprise the last person in it was Lady Washington, alone and without General Washington.

I had called upon Lady Washington several times since my arrival in Morristown, and she’d graciously taken a liking to me, and I to her. It would be impossible not to hold her in the highest regard: she was that rarest of ladies who could put anyone at ease in an instant, and make them feel like the oldest and dearest of friends.

She was of middle age when we met, still handsome if a bit stout, her large, dark eyes full of warmth and her speech soft with Virginia gentility. She was known for her rich taste in dress, and tonight she wore a dark green damask gown with a neckerchief of fine French lace and a magnificent garnet necklace with earrings to match.

“Miss Eliza, I am so glad that you have joined us,” she said as I curtseyed before her. “How your beauty graces our little gathering!”

“Thank you, Lady Washington,” I said, blushing with pleasure at her compliment. “You are most kind.”

She raised her gaze, frowning slightly as she studied my hair. “You are wearing the powder I gave you, yes? That slight tint of blue is so becoming to us brunette ladies.”

“Thank you, yes,” I said, my hand automatically going to my hair. She’d given me a box of her scented hair powder as a kindness, though I’d had to use a prodigious amount of it to dust my nearly black hair.

“You see I am wearing the cuffs you gave me as well,” she said, holding out her plump, small hand toward me. The ruffled cuffs were of the finest white Holland with Dresden-work scallops, sent along with me by my mother as an especial gift for the general’s wife. The cuffs were Paris-made, for although our country was under a strict embargo for foreign goods, my mother (like most ladies of the time) still had her ways of securing the little niceties of life from abroad.

“You must be sure to thank your dear mother again,” Lady Washington continued, “and please tell her how honored I am to be remembered by her.”

“I shall, Lady Washington,” I said. I took this as my dismissal, and I bowed my head and began to back away.

But she had other notions, and took my hand to keep me with her.

“A moment more, Miss Eliza, if you please,” she said. “Here I am prattling on and on, without recalling the one bit of knowledge I was entrusted to share. You note that my husband is not yet here, and I am acting in his stead. He and Colonel Hamilton have been detained on some military business, but they expect to join us as soon as it is concluded. The colonel in particular asked me to share his considerable regrets at being detained, and prays that you shall forgive him.”

I couldn’t keep from smiling broadly with relief, so broadly that Lady Washington chuckled.

“There now, I’d venture he has your forgiveness already,” she said. “You may grant it yourself directly.”

She was looking past me, and without thinking I turned to look in the same direction. The crowd rippled with excitement as His Excellency entered the room, towering over most other men with a stately presence that could command attention without a word spoken. Instead of his uniform, he wore a suit of black velvet, neatly trimmed with silver embroidery and cut-steel buttons, and in every way he epitomized how the leader of our country should look.

But I wasn’t looking at His Excellency. Instead I saw no one but the gentleman behind him, slighter and shorter by a head and yet the only one who mattered to me. He was easy to find, his red-gold hair bright like a flame, and uncharacteristically unpowdered for this formal occasion. To my gratification, Alexander was seeking me as well, and as soon as our gazes met I saw him smile and unabashed pleasure light his face, as if no other lady than I were in the room for him.

The general came forward to claim the first dance with Mrs. Lucy Knox, the wife of Major General Knox, and led her to the center of the room to open the assembly with the first minuet. The rest of the guests stood back from the floor to watch them dance with respect (and admiration, too, for together they cut an elegant figure), and as the musicians played, the general and Mrs. Knox—he so tall and lean, and she so stout—began the minuet’s elegantly measured steps.

Yet Alexander hung back and I remained with him, away from the dancing and the other guests.

He took my hand. “Pray forgive me,” he whispered, “I was with His Excellency, and the delay was unavoidable.”

“Of course you’re forgiven,” I replied. “Your orders and your duties to the army and to the country must come first. I understand, and always will.”

“You will, won’t you?” he asked, his voice rough with urgency. “You’ll understand, no matter what may happen?”

“Of course I will,” I whispered, and it seemed more like a vow, an oath, than a simple reply. “Never doubt me.”

He raised my hand and kissed the back of it, a bold demonstration in a place so crowded with witnesses and ripe for gossip. But no one was taking any notice of us whilst the general was dancing, and I did not pull free.

Gently he turned my hand in his and kissed my palm. I blushed at his audacity, but it was far more than that. I felt my entire body grow warm with sensation, melting with the heat of his touch. This was what I’d wanted, what I’d longed for. When at last he broke away, an unfamiliar disappointment swept over me, and I felt oddly bereft.

If I felt unbalanced, then he must have as well, for his expression was strangely determined and intense. Within the General’s Family he was called “The Little Lion,” and for the first time I understood why. This was not the Alexander I’d seen this last fortnight sitting politely in Mrs. Campfield’s sitting room. This was a different man altogether, and while part of me turned guarded and cautious, the larger part that contained my heart, and yes, my passions, was drawn inexorably toward him.

“Orders had nothing to do with why His Excellency and I were detained,” he said to me, his fingers still tight around mine. “It was instead the matter of my future, my hope, my very life, and yet he will not listen, and refuses it all.”

I glanced at the general, dancing as if he’d no cares in this world or worries for the next.

“Then tell me instead,” I said.

“Come with me outside,” he said, leading me toward the door. “We cannot speak here with any freedom.”

Venturing outside alone in the dark with a gentleman was one of those things that virtuous ladies did not do. But for the first time in my life I didn’t care what anyone might say or think. I fetched my cloak and he his greatcoat, joined him at the storehouse’s rear doorway, and together we slipped outside.

“This way,” he said softly, leading me behind the storehouse and away from where the sleighs and horses were waiting with their drivers gathered for warmth around a small fire. “No one will see us on the other side.”

Most times when a gentleman and lady leave a ball or assembly, there is a moonlit garden with shadowy paths and bowers to welcome them. But here in Morristown, all trees and brush had long ago been cut by the army for firewood and shelters, and the only paths were ones trodden by others into the snow. There was no pretty garden folly or contrived ancient ruin; instead we stood beside the rough log walls of a military storehouse. The only magic that Alexander and I had was the moonlight, as pure and shining as new-minted silver spilled over the white snow and empty fields.

But that magic, such as it was, held no charm for Alexander now.

“The general still refuses to promote me for an active post, and will not consider a command for me to the south,” he said, his voice taut with frustration. Despite the cold, he hadn’t bothered to fasten his greatcoat, and the flapping open fronts only exaggerated his agitation.

“Oh, Alexander,” I said, for I’d heard this from him before, though not with such vehemence. “Did you present your case for a field command to His Excellency again this evening?”

“I did,” he said. He was pacing back and forth before me, the heels of his boots crunching over the packed snow. “He claims he cannot grant me a command without giving offense—offense!—to other officers who surpass me in seniority. Instead I must be mired here in endless drudgery without any hope of action or glory.”

Dramatically he flung his arms out to either side, appealing to me. “Do you know how I passed this day, Betsey? Can you guess how I was humbled?”

I suspected there would be no acceptable answer to this question, not whilst he was in this humor, yet still I ventured one. “I should guess you were engaged in your duties as ordered by His Excellency.”

“Oh, yes, my duties,” he said. “Such grand duties they were, too. I tallied and niggled the expenses incurred for the feed of the cavalry’s mounts, horse by horse. My duty was to count oats and corn and straw like any common farmer in his barn.”

I sighed, my feelings decidedly mixed. I knew he was dissatisfied with his role in the winter encampment. Although he was the general’s most valued aide-de-camp, he chafed under that honor and the duties with it, and longed for a posting where he’d see more active duty and combat with the enemy. I wished him to be happy, yes, but I also wished him to stay alive, and I dreaded the very thought of him in the reckless path of mortal danger.

He took my silence as encouragement, and continued on, his voice rising.

“The general would unman me completely, Betsey, and replace my sword forever with a pen,” he said. “There is a sense of protection to the position, of obligation, which I find eminently distasteful. How can I be considered a soldier? Each day that I am chained to my clerk’s desk is another that questions my courage, my valor, my dedication to risk everything for the cause.”

This, too, I’d witnessed before. Alexander was a gifted speaker, and once he fair had his teeth into an argument, he could worry it like a tenacious (but eloquent) bulldog for hours at a time. His skill with words was a wondrous gift and one that left me in awe. But beneath my cloak tonight I was dressed for a ball, not an out of doors declamation beneath the stars, and I needed to steer him gently toward a less furious course before my teeth began to chatter.

“His Excellency knows you’re not a coward,” I said, tucking my hands beneath my arms to warm them. “Your record in battle has already proven your courage. But there are no battles to be fought by anyone in the winter season, and—”

“There are in Georgia, in Carolina,” he said, the words coming out as terse small clouds in the cold air. “Laurens has written me of brisk and mortal encounters with the enemy.”

I sighed again. John Laurens was another lieutenant colonel and former aide-de-camp, and Alexander’s dearest friend in the army. Laurens had left the General’s Family before I’d arrived, but I felt as if I knew him from Alexander’s descriptions of his friend’s character, handsomeness, and daring; he’d also been born to wealth and privilege as the son of the wealthiest man in South Carolina, accidents of fate that greatly impressed Alexander. His fondest reminiscences of Laurens, however, involved hard-fought battles, gruesome wounds, swimming rivers under enemy fire, and having horses shot from beneath them. These tales I found terrifying, even though I understood from Papa that this was how soldiers behaved during wartime. Little wonder that I also believed—though I’d never say so—that Colonel Laurens was responsible for much of Alexander’s restlessness.

“You’ve told me before that those are random skirmishes,” I said as patiently as I could. “Colonel Laurens admits that himself, does he not?”

He grumbled, wordless discontent. “He does, on occasion.”

“And you’ve said yourself that they’re risky ventures,” I continued, “and of no lasting value to the cause.”

He paused his pacing again, and tipped his head to one side to look at me. The moonlight caught the curl of his hair beneath the brim of his hat, like a flame against the dusky sky.

“Not when compared to larger, more organized campaigns, no,” he admitted, finally sounding a fraction more reasonable. “Yet every action, large or small, has its use in deciding a final victory.”

“But even the general accepts that there is a season for battle, and a season for rest.” I kept my voice logical yet soothing, too, knowing from experience that was what would calm him. “The letters you now write for the general, the plans you make for the army for the spring on his behalf, are far more important than any random encounter in the Carolina wilderness.”

“But there’s no glory in it, Betsey,” he said, his earlier impatience now fading into a sadness that touched my heart. “You know I’m a poor man, without family or fortune. I’ve made no secret of that with you.”

“But consider how far you have come on your own,” I said, “and how much you have already achieved.”

“It’s scarcely a beginning,” he said. “I need to make my name for myself now, during the war, and that I can’t do scrivening away at a desk. I cannot gain any measure of fame unless I return to the battlefield, and yet because I have no familial influence of my own, I will never be advanced to a higher command.”

“You have friends,” I said softly, trying not to think of what Kitty had told me earlier. “Important friends, in the army and in Congress. Friends who appreciate your talents, and regard you as you deserve. All will come to you in time. I’m sure of that.”

“In time, in time, in time,” he repeated in despondent singsong. “What if I can’t wait, Betsey? What if you can’t? I want to be worthy of you, and yet I have nothing of any value to offer you.”

“Oh, Alexander,” I said. “You have so very much to offer to me! You’re brave and honorable and kind and clever, with a hundred other qualities besides. You have grand ideas and dreams that only you have the power to make real. You could never raise your sword against the enemy again, and still I’d be the one who wasn’t worthy of you.”

“My dear Betsey.” He smiled, a weary smile, yes, but a smile nonetheless. “No wonder you’ve become so dear to me, and so indispensable, too. I do not think I could bear this winter without you. You’re my very Juno, filled with the wisest counsel, combined with the beauty of Venus herself.”

“You say such things.” I smiled, too, but uncertainly. I knew he’d just paid me a compliment, but unlike Angelica, I’d no aptitude for scholarly endeavors, and I was never quite sure what he meant when he spoke of ancient goddesses.

“I do indeed,” he said, finally coming to stand close to me. “And you are cold, aren’t you? Let me warm you.” He wrapped his arms around me and drew me close, folding me inside the dark wings of his heavy wool greatcoat. I went to him and snugged next to his chest as if I’d found my true home. I felt safe and protected with his arms around me and my cheek against his chest, and so contented that I could not keep back an unconscious sigh of pure joy.

He chuckled, and drew me closer. “Sweet girl,” he said. “You thought you’d come here to dance, not to shiver in the moonlight with me.”

I tipped my head back to see his face. I’d been so occupied with our conversation that I’d nearly forgotten about the dance, and with his reminder I was again aware of the music coming faintly from the assembly within the storehouse. The minuet was long past done. What I heard now was an allemande, and I wondered how many other dances had been danced since we’d left the assembly. By now our absence must have been noted—I doubt I’d ever escape Kitty’s sharp eyes—but I didn’t care. This time alone with him was worth any price.

“I’ve never seen a moon such as this,” I said breathlessly, turning a bit in his arms to better see the sky. “It’s like magic, isn’t it? A full moon wrought from silver, there in the sky.”

His hands had settled familiarly around my waist above the whalebone arc of my hoops, and just that slight pressure of his palms against my sides was making my heart beat faster.

“You should see how the moon glows in the sky over Nevis,” he said. “There’s no magic involved, but a phenomenon caused by the island being so close to the equator. It’s every bit as bright as this, with the brilliance reflected and magnified by the sea below it.”

“Truly?” I said, trying to imagine what he described. “You make it sound very beautiful.”

“Oh, it is,” he assured me, but the way he said it made me think perhaps it wasn’t. “A sight worthy of the finest poets.”

He fell quiet, gazing up at the moon. He almost never mentioned the island where he’d been born, and I longed to know his thoughts.

“Does this make you wish to return home?” I asked. “The moon, I mean.”

“Nevis is no longer my home,” he said bluntly, “and I never wish to return. If I’d remained there, I would by now be dead. It’s the way of that place.”

The sadness in his voice was heartbreaking. “But you’re here now,” I said. “Beneath an American moon, not a Nevis one.” I turned around to face him again, and placed my palms lightly on his chest. My right hand rested over his heart, something I didn’t realize until after I’d done it.

“You shall do wonderful things, Alexander,” I said fiercely, gazing up at him. “I’m sure of it. You are a man born to do great things. I only pray that I’ll be there to see you do them.”

Suddenly he smiled, and so warmly that I forgot I’d ever been cold. “You pray a great deal, Betsey.”

“I’ve prayed for you ever since that first night, exactly as I promised,” I said, my fingers spreading over the front of his waistcoat. “My prayers have been answered, too.”

“Perhaps mine have as well.” He reached up to cradle my jaw with one hand, gently turning my face up toward his. “You’re kind and generous and tender to a fault, especially where my wretched self is concerned. Have I told you that you’re beautiful as well?”

“You have,” I said playfully. “But I will listen if you choose to tell me again.”

He chuckled. “You are beautiful, dearest, surpassing beautiful and unmercifully handsome, and I’ll never tire of telling you that pretty truth. You have so addled my wits that the other night when I returned to headquarters from seeing you, I could not recall the password. Of course the sentry knew me, the dog, but he wouldn’t let me pass until Mrs. Ford’s boy rescued me with the proper word. That’s all your doing, Miss Elizabeth.”

I laughed, picturing him foundering at the front door before a grave-faced guard. “You cannot fault me for that!”

“I can, when it’s the truth.” His smile faded. “You speak of the future as if you can foresee what it holds. You’re so wise, perhaps you can. Do you know how honored I’d be to have you beside me in that future, Betsey? To know you’d be with me always, as you are now?”

My heart was beating so fast that it was almost painful within my breast.

“I could wish for nothing more than to be with you like that, Alexander,” I whispered. “Nothing.” I was trembling, for I’d never spoken like this to another man, nor had I ever desired to. “I—I love you, Alexander Hamilton.”

I wish I could have preserved that moment forever, how he looked at me with such boundless emotion and regard, as if I were the most worthy woman in the world.

“I love you, Elizabeth Schuyler,” he said solemnly, and yet I was sure I heard a tremor to his voice to match my own. “My joy, my happiness, my love. Do I have your leave to address your father?”

I nodded, not trusting my voice. I suspect he didn’t trust his, either, for he spoke no further.

Instead, he kissed me.

How dry and dull those words seem when writ on paper! How, in their simplicity, they lack the riches that Alexander’s first kiss held for me! At first he barely touched his lips to mine in the kind of chaste salute that would have pleased even Aunt Gertrude. This kiss was an honorable pledge meant for marriage, the most sacred of sacraments for any woman, and as our lips came together, I realized his honorable regard and devotion for me. I felt cherished, and I felt loved.

But as glorious as that moment might have been, it would not long suffice for either of us. I will be honest: I’ll include my own impatience, however unseemly for a lady that may appear, for in this as in so many things Alexander and I were already in perfect union. That first brush of his lips over mine was like a spark to overdry tinder, and at once the heat of desire washed over me.

In innocent eagerness, I pressed my lips more ardently against his, and at once he responded. He slipped his hand from beneath my jaw to the back of my head and tangled his fingers into my hair, and slanted his mouth over mine to deepen the kiss. My lips parted beneath his, and with a hunger I’d never realized existed within me I tasted him as he tasted me. The heat of his kiss burned me with its unexpected passion, and made me yearn to become his even more completely. I slid my hands around his shoulders to steady myself, and shamelessly stretched my body against his.

I am not certain how long that first kiss lasted, there in the silver-bright moonlight. It seemed both an instant, and an eternity, with the only certainty being that I did not wish it to end. Yet like all things, finally it did, when with obvious reluctance Alexander lifted his mouth from mine.

I opened my eyes, still dazed with heady bliss. He was almost frowning as he gazed down at me, his lips still parted and his breathing quick, as was my own. My thoughts were muddled: I was a lady born, a Schuyler, and not one of the slatterns who frequented the camp. I tried to push away from him, belatedly fearing he’d think ill of me for encouraging such freedom.

“I—I am sorry, Alexander,” I stammered in confusion, my cheeks hot. “Forgive me for—”

“Hush,” he said softly, placing his fingers lightly over my newly kissed lips. “It must be I who apologizes, not you, dearest Betsey, nor can I lay the fault on the moonlight. Even in your innocence, you have that power over me. You tempt me so much, when I must show more regard for the lady whom I pray will one day soon be my wife.”

I smiled shyly, liking the notion that a lady-wife could be tempting, too, and pressed my lips against his fingertips.

“One day,” I breathed, liking those words. “And soon.”