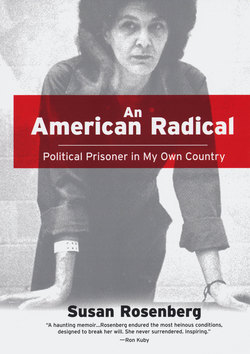

Читать книгу An American Radical: - Susan Rosenberg - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3 Detention

ОглавлениеAFTER WHAT SEEMED like an eternity, the next morning Tim and I were taken to our arraignment in Camden, New Jersey. The courtroom was filled with more armed agents than I had ever seen in any other courtroom before. We were charged with conspiracy to possess and transport weapons, explosives, and false identification across state lines. We pled not guilty and said we were revolutionaries. At first, bail was set for each of us at five million dollars, but later in that same proceeding bail was revoked and we were held over, pending a formal indictment. Some time after the arraignment was over, Tim and I were bundled into cars and driven at one hundred miles an hour to the New York Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) in Manhattan. The building, a large concrete structure amidst many government buildings, including the courts, sits in downtown Manhattan. Bordering it on one side is the Brooklyn Bridge and Chinatown on the other. It had a brutal appearance to me as we drove down the back street to the underground entrance. Helicopters buzzed overhead, and the blaring sirens and flashing lights pierced through the late-night quiet. Our arrival was being announced. We were the prize catch and everyone had to be made aware of it.

We had not eaten or washed our hands or been alone for two days. Tim and I had not been able to speak to each other. We had only gazed at each other in abject shame, with profound feelings of defeat and an occasional burst of defiance. We had been screamed at continuously and beaten up. We were emotionally and physically exhausted. Earlier someone had lifted me off the ground by my handcuffs, so as we stood at the elevators my arms, cuffed behind my back, were aching. When no one was looking, I slipped out of the cuffs. One hand at a time came out easily. It was my first mental game with capture, and it made me feel alive to give in to the thrilling desire to escape. Up until that moment, for most of the time, I had had the overwhelming desire to be dead.

Our identification with wanted black revolutionaries had provoked the police and the FBI into a state of frenzy. Their adrenaline production was in overdrive and they wanted to dispose of us so that they could get to work hunting down our associates. After we were booked, photographed, and deposited into detention, they locked us up in the bull pens. It was time for “cold cooking,” a term I did not know then, but a reality that I would come to experience again and again. It meant being left to stew in a cold, isolated, and extremely uncomfortable environment. It could last for two or three days. Here I was shoved into a federal holding cell, empty, dark, and enormous. It had a closed front, the wall only marked by a heavy metal door with a very small window in it. Several marble benches, incongruous amid the dinginess, ran the length of the walls; two more sat in the middle of the room. The architecture was imperial decay, which struck me as funny, particularly when I noticed the steel toilet in a corner caked with urine and filth. There were messages carved wall to wall—tito was here, sam, shit, pete fucks agnes—all with distinct markings. As I examined them, it occurred to me that they were the modern equivalent of hieroglyphics. I understood the need to make a mark, to leave a message, to scream out loud in this disembodied hole, “I was here. Don’t let me disappear.” Then I saw one that read long live black liberation. It relieved me greatly to see this one. I was not the first political person who laid on that bench. It was such a simple thing, yet it gave me much comfort. It was a sign that allowed me to temporarily put aside all the terrible feelings of pain and loss—the agony over the possibility that others would get caught as a result of our mistakes—that I had experienced since my arrest.

I inspected all the crevices and corners and saw no cameras. It was completely quiet and no one was peering at me through the slot in the door. I lay down on the bench and stretched all my muscles. Alone in that first of what would be hundreds of bull pens, I began to bargain, with whom I cannot say, but I began to talk to another party outside of myself. It wasn’t prayer exactly; it was more like the beginning of what would become a mantra. I wasn’t talking to God. It was not God that I prayed to; for me, it was the consciousness of being human. That was my God. The ability to locate beauty in the hideous, to create something in the face of devastation (man-made or otherwise), to determine one’s own fate—those were my commitments and, in a spiritual sense, they were the things that I looked to for strength. I did not know that then, though. At the time, I drew on more radical examples of people who had been in the revolutionary struggle before me. I thought, How do I resist? I thought of people from the national liberation struggles who had raged throughout history, people like Bobby Sands1, who had died on a hunger strike in prison while fighting for Irish independence; Lolita Lebrón2, who had spent twenty-five years in U.S. prisons for the cause of Puerto Rican nationalism; and John Brown, the greatest ally to the black freedom struggle in American history, who had been vilified by the government and then hung from the neck. As I lay on that bench I retreated even further into the mental ritual I would go through again and again in the years that would follow, circling back to my beginnings in order to locate myself somewhere in the history of radicalism. And in search of an answer as to why I had made the choices that had landed me in that bullpen.

I was born in 1955, in the aftermath of the Second World War. I grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, an only child. My father, known to his friends as Manny, short for Emanuel Rosenberg, was a World War II veteran and a dentist. His dental practice was in Spanish Harlem, where he worked with the most underserved and marginalized communities. There were occasions when he got paid in goods and services rather than money, and he would bring something home that had “fallen off the back of a truck.” He had traveled to Selma to help during the civil rights movement and had always volunteered his skills. My mother, Bella, was a theatrical producer and former film editor. She helped struggling visual artists and writers to begin their careers. My parents believed in civil rights, the early anti-nuclear movement, and they were against the Vietnam War.

In 1964, when I was eight years old and attending the Walden School, Andrew Goodman, who was to become one of its most famous alumni, was slain by the Klan for his participation in the voter registration drive in Mississippi. Even though he was my senior by more than ten years, his younger brother was in the class ahead of me, and his family was very active in school affairs. The school became a base of support for the civil rights movement, raising money and recruiting people to go south. James Chaney was assassinated along with Andrew Goodman. His family was from Mississippi, and his brother Ben, who was twelve years old at the time, was sent north and later enrolled at Walden. He became my friend, and for the next several years I acutely watched events with the added perspective of what I imagined to be Ben’s experience.

I continued at Walden through high school, during the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement. At first I went to anti-war demonstrations in New York with my parents. But, by 1970, I was attending with others from my school. That year, I went to the big anti-war mobilization in Washington and I got separated from my friend Janet and walked into a police action against people who had raised a North Vietnamese flag on the Justice Department building. I had never seen people getting beaten with clubs and dragged into wagons, except on television. Then the police let loose tear gas to disperse the crowd of thousands. I ran to get away from the gas and the police until I fell on a grassy slope and pressed my head into the grass to stop the searing pain and tears that I had gotten from just a small whiff of it. When I returned home, I discovered that other Walden students had been beaten up by the police. Furious, I joined the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, an anti-war group that was organized by college students who were members of Students for a Democratic Society. My high school chapter organized teach-ins and actions against the war in schools all over the city. The Vietnam War, specifically what our government was doing against the people of Vietnam, was predominating all of my thinking about the world and my own responsibility in it. Daily, I watched on TV the carpet bombings, the napalming of whole villages, and the tiger cages that were built out of bamboo that were smaller than a bathtub and used to torture pro-Vietcong villagers. As the body counts got higher and higher on both sides, I groped for any justification that made sense.

I was fifteen in 1970, and along with millions of other people across the globe, I wanted to make change, stop war, and build a peaceful and just world. It seemed possible because there were clearly drawn sides between war profiteers and supporters of the establishment and the majority of people who were resisting and demanding transformation.

Perhaps my choices and life course were the result of a combination of nature and nurture. Despite being surrounded by middle-class privilege, I seemed to be aware of injustice and inequities around me. At the age of five I had first seen a legless man on a skateboard and refused to go into a store to buy shoes, because, as I angrily explained to my mother, how could I buy shoes when the man had no feet. Maybe from that moment when I understood the oppression of others, followed by the images from Selma, Alabama, and Haiphong, Vietnam, and the rows and rows of burned-out houses along Morris Avenue in the Bronx, my skin had become so thin that the pain and suffering of others penetrated my own blood and mingled with it and drove me to an agony of distraction that meant I had to act.

Fourteen years later I still believed in the need for change. I began to converse with all those radical spirits, comparing what I imagined they had gone through to what was happening to me. I thought, If it isn’t worse than this, I can manage it. But then it got much worse.