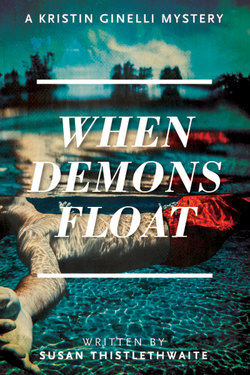

Читать книгу When Demons Float - Susan Thistlethwaite - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеGo to university? Modern day propaganda factories

—Nordicheathen@Herrenvolk.com

Monday

After I had finished glaring at the windows of the buildings on the quadrangle, I realized I had time to hurry home and have breakfast with my twin boys, Sam and Mike. Adelaide had already texted that the emergency faculty meeting would start at 8 a.m. I looked at my watch. It was barely seven. As I jogged along the sidewalk, I reflected how much I could get done if I always got up this early. Hah. No chance of that. I am not a morning person.

The boys and I lived a scant three blocks from the campus, the reason, and really the only reason, I’d bought our aging Prairie Victorian house. It needed substantial renovation, and the contractor I’d hired had barely started. He’d taken my deposit check, sent some painters who took months to dab paint on the outside, and I hadn’t seen him since. Another problem to address, but not right now.

A live-in couple, Carol and Giles Diop, helped me with the boys and the household chores. Carol, who was from Maine, was finishing a Masters degree at the School of Social Work. Giles, who was from Senegal, was a math Ph.D. candidate. They had a separate apartment on the top floor of the rambling wreck we called home. I’d texted Carol that there was an on-campus emergency before I had dashed off before dawn.

“Mom!” There was a joint chorus from the back of the house where the kitchen was located as soon as I opened the door. Our golden retriever, Molly, woofed a greeting, but stayed where she was. She would never abandon her spot under the kitchen table while the boys were having breakfast. Food rained down for her like mana from heaven when the kids ate. Dog theology is very literal. Why not? It works for them.

I headed back to the kitchen and greeted the boys, who were bouncing around in their seats at the kitchen table, and Giles, who was standing by the stove, stirring a heavy, cast-iron pot. Carol must have been upstairs. Giles did all the cooking and, if your stomach could take the spices, it was marvelous. What I smelled was Senegalese flour porridge. If you didn’t stir it, I knew, it became a big lump.

“You have not eaten, yes?” Giles said, not turning his head from the pot. “I have made Bori. It is ready.” He lifted the heavy pot and turned, carrying it over to where the boys and Molly were squirming around waiting. Giles was about 5’8” and very thin, but he was also very strong. His wiry arms handled the cast-iron like it was a teacup.

I got my own bowl out of the cupboard and hurried over, holding it out like I was one of the kids. Giles ladled the Bori into our bowls, gave us all his shy smile, and then, seeing Molly’s disappointment, went to her bowl on the floor and scooped some of the porridge into it. Giles cannot bear to disappoint anyone.

The boys and Molly started literally inhaling their food. Not a moment was spared by my children to converse with Mom. Usually, at least Mike, my oldest by about 15 minutes, would have quizzed me on where I had gone so early. But now, at seven, it was food first, talk after. They could eat nearly as much as I could. I thought perhaps they were in a growth spurt. I looked across the breakfast table at the two heads bent over their bowls. Their thick, chocolate brown hair was tousled and when they looked up with their dark brown eyes, they were the mirror image of their father, Marco Ginelli. My Marco. A Chicago detective who had been killed in the line of duty when they were less than a year old. I still believed Marco had been murdered, but I’d never been able to prove it. I felt a sharp pang of grief. I shook myself. Of course I was feeling emotional given the way the day had begun. Emotion bleeds from one hurt to another.

“So, guys, backpacks packed and ready to go?”

“Yeah, yeah,” Sam said, one hand suspiciously under the table. I could tell he was holding his bowl down for Molly to lick.

“Great, but Sam, don’t feed her directly from your bowl, okay?”

Mike got up and made a big show of carrying his bowl over to Molly’s and scraping out the leftovers. Not that there was much in the way of leftovers.

“See, Sam?” Mike said over his shoulder, deliberately baiting his brother. “So, whatever,” Sam said. He got up, put the licked-clean bowl on the table, gave me a big hug and a kiss on the cheek, and then looked over at Mike with triumph, and ran down the hall. Sam was perfecting his use of charm to get around my instructions. I should have corrected him, but he’d distracted me with the hug and the kiss. And scored off obedient Mike as well.

“Bye, Mom,” said Mike, and he too ran down the hall, Molly at his heels.

I could hear Carol in the front hall telling them to zip up their windbreakers. She normally walked them to school as it was right on the way to the building where she had her own classes.

Giles was ladling the rest of the Bori into another bowl. I saw there was coffee, and I got myself a cup. I waited until Giles sat down with his own breakfast and the front door had closed. Then I sat down opposite him. I needed to let him know what had happened on campus. As an African immigrant, the noose and the flyers were, in a very cruel way, directed at him as well as Dr. Abubakar. I cleared my throat.

“Giles, I was called out because there was a very disturbing incident on campus some time during the night.”

Silently, Giles put down his spoon, took his cell phone out from his back pocket and tapped the screen. He passed it over.

“Connards,” he said quietly and then picked up his spoon and resumed eating.

I scrolled through photos attached to a text he had received. Well, yes, they were assholes. All too true in any language.

It was all there, the noose, Alice cutting it down, close-ups of the flyers and what they said, the campus police cleaning them up, and then even my act standing in the middle of the quad. I was starting to feel a little embarrassed by that. Alice was right. I was not entirely rational when I’d taken a big hit of coffee on an empty stomach early in the morning. I squinted at the time on the small screen. These had been sent nearly an hour ago. That fast.

I had read an article about what was now being called the “infopocalypse,” or at least I thought that was the term. Basically, the theory was that the end of history, that is, the apocalypse, was being ushered in by the increasing speed and spread of social media used to construct fake realities. This fake “white pride” performance was designed to warp and distort the real nature of what the university was and what it aspired to be. These jerks had gotten their hate out so fast that everything else the administration might say about that would be reaction and most likely ignored in the noise or derisively called “fake news.”

“I’m sorry, Giles,” I said, looking up from the screen. “This kind of hate is not right, not who I hope we are as a country.” Even to my own ears, I thought I sounded like Barack Obama.

“But yes, it is,” he said, gesturing at the phone images with his spoon. “That image, the rope, it is American history, right? It is from right after slavery. These kind of white people now, they want to bring that back, no?”

“Well, yes, they do,” I admitted. “But we can’t let them win,” I said and then winced. I looked at his dark visage, now set as if carved in stone. “I know, I know, they won this round with this stunt and then the way they blasted it out. But it must be stopped.”

“And how do you plan to stop the next, as you say, ‘stunt’?” Giles asked quietly.

“I wish to hell I knew,” I said. I looked at his solemn face. “What do you think we should do about it?”

Giles bent his head over his bowl and gazed into the porridge.

“I am contemplating that. Of a certainty, I am contemplating that.”

And he resumed eating.

✳ ✳ ✳

I hustled back to campus and jogged up the three flights of Myerson, the aging building where most of the humanities offices and classrooms were now located. No one ever took the rickety elevator if they could help it.

Even before I reached our floor, I could hear raised voices. I thought it was just about 8, but it sounded like the colleagues were already going at it. I stopped for a moment to throw my backpack and light jacket into the office I now shared with Dr. Abubakar. Yes, we were reduced to sharing offices. Once upon a time, Philosophy and Religion had possessed several more, very large offices down this corridor, but now three of them had been converted into one large classroom/meeting room and a smaller seminar room. We’d had to do that when our second-floor classrooms had been made into small offices and even smaller classrooms for the ever-shrinking Sociology Department. And to think that not long ago, the intellectual reputation of this university had been carried by its extraordinary work in Sociology. Now we were known for the Business School and its ghastly work in trickle-down economics. Sure, why not? Cut the very disciplines like sociology or philosophy that would help you understand why that kind of economics was a fraud.

I hustled down the poorly lit hall, aware that I was already getting irritable, and I didn’t even know precisely what my faculty colleagues were arguing about. But I suspected.

As I entered, I saw Adelaide sitting at the head of the very long table that ran down the center of the room. Behind her, faux-medieval, stone tracery held stained glass windows that split the watery Chicago sunlight into shards of color. The colors spilled over the back of Adelaide’s head and shoulders, making her look like she was piously sitting in church. Her face, though in shadow, showed narrowed eyes and pursed lips. Adelaide wasn’t feeling pious, she was feeling pissed.

I could see why. Dr. Donald Willie, Associate Professor of Psychology of Religion, was standing in front of his chair, pontificating in a raised voice. At least, I thought he was standing. He was so short it was sometimes hard for me to tell. His narrow face was red with rage, and he was blowing out his words under his unfortunate mustache. I disliked him intensely. In incidents nearly a year ago, he had shown himself to be a coward and even a liar, as well as one of those squishy, faux-liberal, white men who are actually deeply racist and sexist. He had been on leave last semester, and I’d hoped he had been using the time to find another job. No such luck. I struggled to listen to his words as they blew out between his thin, pale lips.

“Unacceptable risk, completely unacceptable risk” was what I thought he was now practically shouting. It is actually hard to shout sibilants. He unwisely accompanied this angry hissing by shaking his finger at Adelaide. Now that, Donald, I reflected, is a big mistake.

Adelaide’s face turned from merely stern to darkly ferocious in less than a second. I thought, for one scary moment, her head was swelling. Donald took one look and abruptly sat down.

Our newest colleague was sitting very still, maybe because he was stunned. I didn’t know how they conducted faculty meetings at Oxford, but I bet it wasn’t as ridiculous as this. I had taught summer school at Oxford University for several weeks a few summers ago. I’d drunk sherry in tiny glasses in the Faculty Commons, but I had not been asked to attend meetings. In the Commons, at least, everyone had been civil.

This would be Dr. Abubakar’s first American faculty meeting. What an introduction. He was sitting at the table on the opposite side from where Donald had just been standing. In the momentary lull, I pulled out a chair next to him and sat down. He didn’t even turn his head. I could only see him in profile. His jaw, with a closely cropped black beard sharply outlining it up to his short black hair, was set, though I could see a muscle working in his dark cheek. He was probably trying to hold in several choice words. Then he took off his glasses, put them on the table and pinched the bridge of his nose.

Adelaide addressed me with what sounded like relief.

“Kristin, glad you’re here. I know you were on the quad this morning when the noose and the leaflets were found.”

There was a kind of strangled gurgle from Donald, but Adelaide ignored it.

“Now, unfortunately, pictures of that, as well as the work of the campus police to remove those items, are circulating around campus, including photos of what the flyers said. Would you give us a brief update and anything the campus police have learned?”

I hesitated. Then, Adelaide glared at me, and I hurried into speech.

“I assume you’ve all seen the photos, including what the flyer said, as they have already circulated widely. I don’t need to rehearse that. I can tell you that the campus police searched the surrounding buildings, but as far as I know haven’t located anyone they thought was involved. But they were there. And more than one.”

I took out my own phone from my pocket, put it on the table and just tapped it to make my point.

“The photos I’ve seen of the active scene were from several different angles, all at approximately the same time. That indicates more than one person is involved. Moreover, I believe this is a hate crime and should be investigated as such. The perpetrators should be found and prosecuted. I also think it is a coordinated effort to stop Dr. Abubakar’s announced lecture.”

I turned in my chair and addressed him.

“Dr. Abubakar, I think we need most of all to hear your thoughts.”

Adelaide nodded, but before Aduba could speak, Donald broke in.

“It is obvious it is too dangerous for him to give this lecture,” he puffed. “I don’t see why we are even discussing it.”

Whitesplaining. Typical. As was the deliberate use of a pronoun rather than a colleague’s title and name. And, of course, what Donald really meant is “I think it is too dangerous for those of us who teach in this department, namely Donald Willie,” but I didn’t say any of it aloud.

Aduba slowly picked up his glasses from the table and put them on.

“I will not be a coward,” he said. “I will give the lecture as planned.” He folded his arms and looked at Adelaide.

“Well, okay,” she said and made to rise.

“It’s not about cowardice, it’s about common sense,” Donald sputtered, rising to his feet again and glaring at Adelaide.

“It’s not your call, Donald,” I said, not bothering to hide the contempt in my voice. I rose as well and emphasized my words by leaning over the table toward him.

“We’re done here,” Adelaide said firmly. For a large woman, Adelaide was very quick on her feet. She was up and out the door in a flash. I could hear her office door open and then shut with a bang.

Willie quickly followed her out the door, not glancing at either Aduba or me.

Aduba waited a moment. I was sure he didn’t want to encounter Donald in the hall. When he rose to leave, I got up as well and followed him. I was stewing about how to send a more welcoming signal to our new colleague than Willie had. Of course, that wouldn’t be hard. Short of tripping him as he walked down the hall, I could hardly do worse than Donald.

“Aduba,” I said, as he paused at our common office door to insert his key in the ancient lock. I made a mental note to tell him that all the doors on this floor opened with the same key and to be careful what he left in the office. But right now, I didn’t think that was what I needed to blurt out.

“Yes?” he said, finishing unlocking the door and opening it, but not entering. He turned to face me. There was a single line across his forehead. Either he was frowning, or he was squinting in the bad light of our hallway.

“Well,” I fumbled. “Well, I was wondering if you and your wife, and your son would like to come to dinner at my house Saturday night.”

“Our son is only six,” he said slowly.

“Oh, that’s okay, my twin sons have just turned seven. It will be informal, believe me.”

“I think that should be fine, but I will consult my wife and let you know. Thank you.” Then he entered the office, went directly to his desk, sat down and turned on his computer.

I thought for a moment about apologizing for Donald’s behavior, but when I looked at his unyielding posture, I decided instead it would be best to give him some time alone, though the divider that separated our two desks and bookcases scarcely provided any privacy. I turned and looked down the hall at the inviting coffee area Adelaide had set up outside her office when she had become department chair. She had installed a De’Longhi espresso machine with all the trimmings. It made quite a change from her predecessor who might have provided free arsenic to both faculty and students if he had thought he could get away with it.

I walked toward the espresso machine like I was on a tractor beam in a Star Trek movie. I really shouldn’t have any more coffee, but I kept moving toward it. I was trying to cut down on my coffee consumption. I realized it had become an addiction. I’d already had two cups and the day had barely started. But, I kept walking toward the coffee.

I felt like I had spent the whole morning so far in one of those tilt-a-whirl things at the amusement park the boys loved so much. You were spun around and around and then the floor dropped out. You hoped gravity would hold you up. But today, I was questioning even gravity. God damn these white supremacists. That was their goal, to make you question whether your commitments would just drop away and let you fall.

I caved into temptation and got a double espresso. I stood there and took a few sips. I would have liked to talk this morning over with Adelaide, but I knew she was teaching in the smaller seminar room. I deposited my donation in the jar for coffee purchases, cleaned up my grounds from the machine, and turned to head back down the hall. I saw Aduba heading for the stairs. He was leaving the office.

I unlocked the door and sat down on my own side. I finished my espresso, and really, it was excellent, and then I opened my computer. I checked my email first, by habit, and was surprised to already see a note from Aduba accepting the dinner invitation and asking the time. Good sign? I hoped so. I sat back in my chair and went over a possible guest list in my mind. I would invite Carol and Giles, though talking Giles out of cooking, and permitting a caterer in “his” kitchen, would be a little bit of a struggle. Adelaide would be a good addition, I thought, and then, of course, Tom Grayson, a surgeon at the university hospital.

I had been dating Tom for nearly a year. He had patched me up after a knife-wielding assailant had made a deep cut in my arm, and I had fallen for his blue, twinkly eyes, his sandy hair that was always too long, and his profound compassion. But I had kept him at arm’s length for months, feeling disloyal, even after six years, to my Marco. It had actually been Marco’s father, Vince Ginelli, who had gruffly told me six years was too a long time to mourn. Tom and I had become lovers this past summer on a delicious trip to Paris. I reminisced about that for a lovely few minutes and then sighed. Since we’d been back, his surgical schedule, and the demands on my time with parenting, teaching, and sporadically working on my dissertation had meant we mostly communed by phone. Less than satisfactory from a romance perspective.

Still, I picked up my cell phone. I hoped Tom was not in surgery. I had a lot to tell him, starting with the noose and ending up with an invitation to dinner.

I dialed his cell. Amazingly enough, he picked up on the first ring.

“Kristin, hold on, I’m just walking out of a patient’s room.”

I held on. He was probably still on rounds.

“Okay, I can talk. I was expecting to hear from you. Are you okay?” Tom sounded very concerned, and I was a little taken aback.

“Sure, yes, I’m fine. Why wouldn’t I be?”

“Well, there are photos that are all over the hospital of that incident on quad this morning, and you’re in many of them. I assume you were working with Alice on that? Must have been difficult, that’s all I meant.” His measured voice was warm, but careful. We’d had some struggles over his desire to protect me.

I realized I had been too prickly about his concern. Concern was warranted. Being prickly was a bad move, I said to myself. I took a calming breath.

“Thanks. I didn’t realize you’d seen the photos, that’s all. Yes, it was very difficult.” I thought for a moment. I knew Tom kept confidences well, and I needed to work on trust with him. I went on.

“I was most upset about how awful it seemed to be for Alice, and you know how she is, she kept it all inside, and just did the job. But I was furious about how the whole fiasco played out.” I paused again.

“I still am. And we just had a ghastly faculty meeting about it.” Then I realized there were voices in the background, probably a resident trying to get Tom’s attention. I tried not to resent it, but I should get off the phone.

“Listen, Tom, I’ll tell you about that later, but I’ll email you an invitation to dinner Saturday night with my new colleague, Dr. Abubakar and his family.”

“A dinner? Sure, should be . . . oh, and just hold on, Kristin.” I could hear the buzz of conversation around him.

He came back on the phone.

“Sure. Send me that. And can I bring Kelly if she wants to come?”

Kelly was Tom’s fifteen-year-old daughter. He had been divorced, but his ex-wife had died the previous year, and now he had custody of a smoldering tower of teenage girl, who alternately hated me and wanted to be me.

“Well, yes, I guess, if she wants to,” I replied slightly less than enthusiastically.

“Great. Good. Let’s talk tonight.” And Tom hung up.

I looked at the silent cell phone in my hand. Paris seemed a very long time ago.

The cell phone displayed the time. It was only 9:30 a.m. I wondered what the rest of this ghastly day would bring.