Читать книгу The Mistress of Normandy - Susan Wiggs, Susan Wiggs - Страница 10

ОглавлениеThree

Her mind reeling with apprehension at her uncle’s sudden arrival, and her heart snared by Rand’s parting words, Lianna raced over the causeway and bounded into the bailey.

Don’t let him see me, she prayed silently. Please, Lord, not until I make myself presentable. She skirted the band of ducal retainers, ducked beneath the flapping standard of a blood-red St. Anthony’s cross, and headed for the keep. A flock of chickens wandered into her path, panicking as they tangled in her skirts. Shrieking, the chickens scattered, winging up dust eddies and leaving Lianna on her knees.

A vivid oath burst from her as she blinked against the dust. When her vision cleared, she found herself staring up at the unfaltering blue eyes, stark face, and uncompromising figure of her uncle. A wide-cut, squirrel-trimmed sleeve gaped before her as he extended his hand and helped her up.

“You stink of sulfur.”

She blushed. A ripple of mirth emanated from the retainers. Burgundy silenced them with a single powerful scowl.

Abashed, she indicated her gun. “I was out shooting.”

He rolled his eyes heavenward, took a deep breath, and said, “Five minutes, Belliane. You have five minutes to present yourself to me in the hall—as a lady, if you please, not some ragged hoyden from the marshes.”

She dipped her head in a submissive nod. “Yes, Your Grace,” she murmured, and fled to her solar.

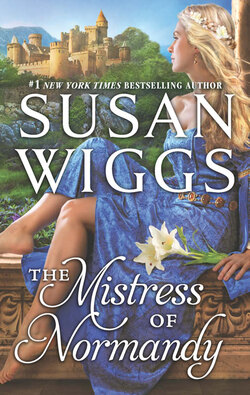

Exactly four minutes later, clad in her best gown of royal blue, her head capped and veiled in silvery gauze, Lianna careened down the stairs toward the hall. Bonne had doused her with a generous splash of rosewater and had scrubbed the last traces of gunpowder from her face. Lianna glanced down at the heavy velvet swishing around her slippered feet. The anonymous pucelle who had enchanted Rand was no more. She longed to fold his image into her heart, to cherish in private his avowal of love. But her uncle was waiting.

Nearing the hall, she slowed her pace, lifted her chin, and glided in to confront the most powerful man in France.

Styled Jean Sans Peur—the Fearless—by friend and foe alike, he kept a stranglehold grip on the political pulse of the kingdom. A ruthless man, Burgundy possessed stone-cold ambition and a penchant for intrigue and deeds done in secret. Men lived at his sufferance and sometimes died at his command.

Yet when Lianna greeted him, looked into his blue eyes, she saw only affection. Pressing her cheek to his chest, she felt the chain mail he always wore beneath his ducal raiments. But the hand he lifted to stir a lock of her hair was gentle. Burgundy’s cold, suspicious heart housed a small, warm corner for his orphaned niece.

“Better, p’tite,” he said. “Much better. You’re lovely.”

She nodded to acknowledge the compliment, although she would have preferred that he notice the new gun emplacements she and Chiang had worked so hard to build. “Come warm yourself by the fire.” She took his wind-chilled hand.

But Burgundy gestured toward the passage at the back of the hall. “I would speak to you in private, niece.”

She preceded him into the privy apartment, waited until he sat, then perched nervously on the edge of a stool.

His eyes full of dark fires, Burgundy looked at her for a long, measuring moment. He sucked a deep breath through his nostrils. “Your disobedience would not hurt so much,” he said quietly, “did I not love you so, Belliane.”

An unexpected lump rose in her throat. “I had no choice. King Henry would have made an English bastion of Bois-Long.”

“Better an English bastion than a French ruin. Where is this husband of yours?”

“Out riding with the reeve.”

“I know Lazare Mondragon,” Burgundy said, his mouth twisting with distaste. “He came begging favors some years ago. I turned him away.” Stroking a long-fingered hand over his Siberian squirrel collar, he added, “They say Mondragon loved his first wife to distraction, nearly grieved unto death when she died. Think you he will hold you in such esteem?”

“I do not need his esteem, only his name in marriage.”

Burgundy sighed. “You could have had better, p’tite.

“Ah, for certes I did.” Frustration shadowed his face. “By marrying Mondragon, you’ve cheated yourself out of a brilliant alliance.”

Unbidden laughter burst from her. “What mean you, Uncle?”

“I speak in earnest,” he said harshly. “By my faith, Belliane, I was saving you for an English noble.”

Shock rocketed through her, then gave way to harsh understanding. So that was why King Henry had meddled with her life.

Bleakly she realized that she was her uncle’s pawn after all, a minor chess piece in his political game. An alliance with England would bring Burgundy’s power to a zenith, enable him to vanquish his hated enemy, Count Bernard of Armagnac, who now controlled the mad French king.

Recoiling from the idea, she took a gulp of air. “My allegiance begins and ends with Bois-Long and France. The promise of winning a title cannot lure me from it.”

“You should not have acted without my consent, Belliane.”

She could not meet his eyes, because he would see her distrust, her belief that his love for her was less compelling than his affinity for intrigue. “Uncle, your wardship over me ended when I reached my majority December last. I was free to contract for my own marriage, free to flout Henry’s directive.”

“You speak treason, my lady.”

“He is not my sovereign!”

“Yet he has styled himself so, claiming the lands won by his grandsire, Edward the Third. Henry will enforce that claim with military might. An alliance with him would be prudent at this time.” The duke’s face pinched into an expression known to strike terror into the hearts of royal princes. But Lianna didn’t flinch as she raised her head.

They sat facing each other, eyes locked. Then Burgundy’s expression changed to grudging admiration. “Would that more Frenchmen had your attitude,” he mused. “We’d never be under Henry’s thumb in the first place.” He strode to the hearth, stood before the blaze. Firelight carved hollows in his cheeks, and worry pleated his brow. Sudden tenderness touched Lianna. Her uncle held a difficult position. Caught up in the madness and dissension between the princes royal of France, Jean had spoken for the common people in the Royal Council, made enemies of the nobles. Now, banished from Paris and opposed by the Armagnacs, he had apparently thrown in his lot with the English.

“Young Henry means to regain the throne of France,” said Jean. “He’s a man driven, at least in his own mind, by divine inspiration. His ambition knows no scruples. Not a man to defy heedlessly.”

“That may well be, Your Grace. But I will not cede Bois-Long to him. I’d be doing my king and my countrymen a great disservice if I were to relinquish the ford to Henry’s army.”

“Your countrymen!” the duke spat. “Who are they, but a lot of quarreling children switching allegiance as capriciously as the winds over the Narrow Sea? France needs a strong guiding hand. Henry—”

“Is another English pretender,” Lianna snapped.

Burgundy sighed. “You may think you’ve thwarted him. Perhaps you have, for the time being. But Harry of Monmouth is too much like you for my comfort. He’s willful, intelligent, energetic.” Burgundy returned to his chair and sat in pensive silence. At length he asked, “What know you of Longwood?”

“Only what I could read between the lines of his overblown missive. This Longwood is un horzain—an outsider, an upstart bastard,” she stated. “His title is barely a month old. And he is a traitor like his father, Marc de Beaumanoir.”

“Beaumanoir was no traitor, Lianna. He simply hadn’t the means to buy his ransom from Arundel.”

“Traitor or not, his bastard will never have Bois-Long.”

Burgundy shook his head. “Parbleu, but you are an exasperating brat. You constantly meddle in male affairs.”

“Only those that concern me and my people, Uncle.” Seeing his face darken, she crossed to his side and took his hand. A cold tongue of apprehension touched the base of her spine. In the game Burgundy was playing, the stake was nothing less than the control of France. “What will you do?” she asked.

“I shall do as I see fit,” he said simply. His silence made her more nervous than any ruthless plan.

* * *

For the first time in her life, Lianna found herself too preoccupied to supervise the feast with her usual meticulous control. Ordinarily she would have chastised the servitor who brought the venison on a poorly polished plate. Her sharp eye would have noticed that the croustade Lombard, made with fruit and marrow, was placed too far from the high table, and that the pastry subtlety of the lilies of France was overdone.

Instead her mind worried her problems like a persistent itch. Burgundy seemed determined to undermine the steps she’d taken to protect Bois-Long. The Mondragons were intent on flaunting their new status. And all the while, sweet, lingering thoughts of Rand, his stunning declaration, the goodness that emanated from him, kept her heart in a state of high rapture.

Ignorant of Burgundy’s displeasure, the Mondragons feasted with delight. Lazare ordered wine casks to be unbunged and called to the minstrels’ gallery for livelier entertainment.

Gervais, darkly attractive and full of confidence, raised his cup. “To my mother,” he said, nodding congenially at Lianna. “Two years my junior, but I pray that won’t keep her from doting on me.” Laughter rippled from the lower tables.

The heat of a furious blush crept to Lianna’s cheeks. She darted a look at her uncle, who sat at her right. Only she understood the significance of Burgundy’s controlled silence, the tightness of his grip around his glass mazer. Damn Gervais, the salaud! He’d not speak so blithely did he realize how tenuous his hold on Bois-Long had become.

Artfully arranging a raven curl over her milk-white shoulder, Macée turned boldly to the duke. “Your Grace,” she said, fluttering her inky lashes, “don’t you wish for Belliane to perform for us? She has a fine hand at the harp.”

Lianna cringed inwardly. Macée had heard her play at the wedding feast and knew her art was poor. But Uncle Jean, merciful at least in this, shook his head. “I’m content to hear the minstrels, madame.”

Macée pouted. Lazare, affecting a dignified air to cover his drunkenness, clapped his hands and called for silence. “My wife will play for us,” he said.

Lianna had no choice but to comply. Lazare was asserting his husbandly control over her; if she wished to prove to Burgundy that she intended to uphold her French marriage, she must act the wife and obey.

Taking her place in front of the high table, she stroked the harp strings with her long, tapered fingers. She performed a chanson de vole that she knew to be a favorite of her uncle’s.

Her voice rang true, the notes hard and bright with unwavering clarity. Still, her style lacked the deep resonance of true artistry.

Burgundy watched her closely, seeming more interested in her somewhat dispassionate countenance than in her singing. When she finished on a clear, contralto note, he was the first to applaud. “Enchantante,” he commented.

She set aside the harp and returned to the table. She couldn’t resist whispering to Macée, “You’ll have to try harder, chère, to belittle me in the eyes of my uncle.”

Macée sent her a sizzling look. “Your art would improve did you not spend so much time in the armory, concocting gunpowder.”

The gibe hurt more than Lianna cared to admit. Of late her femininity had been called into question—by Lazare’s rejection, her uncle’s anger. Even Rand, in his kindness, had made a gentle censure of her interest in gunnery. Now Macée—fabulously beautiful, wise in ways Lianna was only beginning to suspect—challenged her.

“I’m defending the castle instead of warming a chair with my backside,” said Lianna, keeping her tone light.

Macée spoke slowly, as if to a half-wit. “The defense of the castle is men’s work.”

Lianna encompassed Lazare and Gervais with a dismissive glance. “The men in charge of Bois-Long have done little to see to its defense.” Flames of anger ignited in the eyes of both Mondragons. She stole a glance at her uncle. His mouth grew taut with suppressed merriment.

“Well spoken,” he murmured.

“But do you not think,” persisted Macée, “that a lady should have polite accomplishments? After all, if she’s to be received at court—”

A hiss of anger escaped from the duke.

“I’ll practice,” Lianna promised with sudden urgency. She prayed Macée, ignorant of Burgundy’s banishment, would speak no more of the French court. Inadvertently the foolish woman had stuck a barb in an old wound. Desperate to placate him, Lianna turned the subject. “Guy and Mère Brûlot, folk who remember my mother, say she made magic with the harp.”

The hardness left Burgundy’s eyes, as if he’d decided to let the offense pass. “Aye, my sister did sing well.”

“Perhaps there’s hope for me, then. I could send to Abbeville for a music master.”

He shook his head. “The feeling, p’tite, the passion, cannot be taught. It must come from the heart.” He glanced pointedly at Lazare, who seemed to have discovered something fascinating in the bottom of his goblet. “You have the skill. One day, perhaps, true music will come.”

She pretended to understand, because the duke wished her to. But in sooth she knew better than to suppose that passion would improve her singing. Unless... The blinding radiance of Rand’s image burned into her mind. The scene in the great hall receded, and she saw only him, her vagabond prince. The memory of his gentle touch and caressing smile filled her with a sharp, plaintive yearning that she likened to the ecstasy of an inspired poet. Nom de Dieu, could such a man teach her to sing?

* * *

“Sing the one about the cat again,” cried Michelet, tugging insistently at the hem of Rand’s tunic. The boy’s younger brothers and sisters chorused a half dozen other requests.

Rand grinned and shook his head. He set aside his harp and reached down to rumple the carroty curls of little Belle. “Later, nestlings,” he said, stooping to aim the baby’s walker away from the hearth. “I must not neglect my men.”

In the adjacent taproom, Lajoye and the soldiers discussed their forays, filling their bellies with bread and salt meat from the Toison d’Or and wine from a keg the brigands had overlooked. Some of the men vied, with lopsided grins and faltering French, for the attention of the girls.

Rand had avoided his companions since late afternoon. He was too full of unsettled emotions and half-formed decisions to act the commander. Meeting Lianna had left him as useless as an unstrung bow. One hour with her had threatened everything he’d ever believed about loving a woman. Before today, love had been a mild warmth, a comfortable, abiding glow that asked little of him. But no more.

The arrows of his feelings for the girl in the woods had inflicted a ragged wound, a heat that burned with a consuming, continuous fire. He felt open and raw, as if an enemy had stripped him of his armor, left him standing in fool’s attire.

Bypassing the taproom, he walked outside, looked around the ravaged town. Wisps of smoke climbed from a few chimneys. In the rose-gold glimmer of early evening, a woman stepped into her dooryard to call her children to table, while a group of men with their axes and scythes trudged in from the outlying fields. The town was beginning to heal from the wounds inflicted by the brigands. The woman waved to Rand, and he realized with relief that he was now looked upon with trust, not fear. An excellent development. If the Demoiselle de Bois-Long resisted his claim, he’d need to secure the town to use as a retreat position.

He followed a familiar, muffled curse to the paddock. His horses and those of his men occupied the stalls, Lajoye’s livestock having been taken by the écorcheurs. A bovine shape caught his eye. “Jesu, Jack, where did you find that?”

Jack Cade looked up from the milking stool. “Lajoye’s youngsters need milk,” he said. “Spent the king’s own coin on her, down in Arques.” The cow sidled and nearly overset Jack’s bucket. “Hold still, you cloven-footed bitch.” He grasped a pair of fleshy teats and aimed a stream of milk into the bucket. “I made sure Lajoye knows the milk’s from our King Harry.” Leaning his cheek against the cow’s side, he gave Rand a brief accounting of the events of the day.

“Godfrey and Neville ran down a hart and brought it back to Lajoye. Robert—er, Father Batsford, that is, went a-hawking. Giles, Peter, and Darby found the brigands’ route and followed it some leagues to the south, but the thieves are long gone, dispersed, probably, after dividing their spoils.”

Rand frowned. “I did want to recover the pyx from the chapel. ’Twould mean much to the people.”

Jack’s eyes warmed with affection. “Always trying to win hearts and souls, aren’t you?”

Rand smiled. Was he deluding himself to believe chivalry could achieve such an end? “Always skeptical, aren’t you?” he countered.

Jack shrugged. “Take them by the balls, my lord. Their hearts and souls will follow.” Wearily he rotated his shoulders. “I worked like a goddamned swineherd today. And yourself, my lord? Any luck?”

Rand swallowed and stared at the dust dancing in a ray of golden twilight. The rhythmic, sibilant splatter of milk against the sides of Jack’s bucket punctuated the silence. Presently Jack finished his task and straightened. “Well?”

“I met...a girl.”

The milk sloshed in Jack’s pail. Too late, Rand realized his voice had betrayed the feelings he’d kept folded into his heart since he’d watched Lianna run off toward the castle.

Eyes dancing with interest, Jack set down his pail, picked up a stalk of hay, and aimed it at Rand’s chest. “Has Cupid’s arrow found a victim? Welcome to the human race, my lord.”

“Her name is Lianna,” Rand said in a low voice. “She lives at Bois-Long.”

“Better still,” Jack exclaimed, rolling the hay between his fingers. “Surely it’s a sign from above. Merry, my lord, perhaps life won’t be so disagreeable with a ready wench at hand.”

Rand shook his head. “The married state is sacred. And I’d not dishonor Lianna.”

Jack laughed. “Knight’s prattle, my friend. Your commitment to the demoiselle is one of political convenience. No need to be good as gold on her account.”

Rand turned away. “If gold rusts, what would iron do?”

Jack tossed a forkful of hay to the cow and picked up the bucket. They walked out of the paddock. “I for one,” said Jack, “intend to grow right rusty wooing Lajoye’s hired girl. She’s got a pair of—”

“Jack,” Rand warned, drowning out the bawdy term.

“—to die for,” Jack finished.

“I’ve forbidden wenching.”

“Only with unwilling females,” said Jack. “But never mind. When do we go to Bois-Long?”

“King Henry insists on proper protocol. A missive must be sent, and the bride-price, and Batsford must read the banns for a few weeks running.”

“Still in no hurry.” Jack grinned. “That hired girl will be glad of it.” He walked back to the inn.

Caught in the purple-tinged swirls of the deepening night, Rand left the town and climbed the citadel-like cliffs above the sea. A nightingale called and a curlew answered, the plaintive sounds strumming a painful tune over his nerves.

Staring out at the breaking waves, he pondered the unexpected meeting and the even less expected turn his heart had taken.

Lianna. He whispered her name to the sea breezes; it tasted like sweet wine on his tongue. Her image swam into his mind, pale hair framing her face with the diffuse glow of silver, her smile tentative, her eyes wide and deep with a hurt he didn’t understand yet felt in his soul. She inspired a host of feelings so bright and sharp that it was agony to think of her.

There was only one woman he had any right to think about: the Demoiselle de Bois-Long.

The nearness would be hardest to bear. To see Lianna’s small figure darting about the château, to hear the chime of her laughter, would be high torture.

End it now, his common sense urged, and he forced his mind to practical matters. The Duke of Burgundy was at Bois-Long, but his retainers were few. Clearly he did not plan a lengthy visit. Jean Sans Peur could ill afford to tarry with his niece when his domain encompassed the vast sweep of land from the Somme to the Zuyder Zee.

Aye, thought Rand, Burgundy bears watching.

But even as he hardened his resolve around that decision, he knew he’d go back to the place of St. Cuthbert’s cross where he’d met Lianna. The guns, he rationalized. He must dissuade her from working with dangerous and unpredictable weapons. Yet beneath the thought lay an immutable truth. Guns or no, he’d seek her out—tomorrow, and every day, until they met again.

* * *

“Gone!” said Lianna, running into a little room off the armory. “Lazare is gone!”

“Did you think your uncle of Burgundy would let him stay?” Chiang asked, his dark eyes trained on a bubbling stew of Peter’s salt that boiled in a crucible over a coal fire.

A warm spark of relief hid inside her. Ignoring it, she said, “Uncle Jean had no right to order Lazare to Paris.”

“Not having the right has never stopped Burgundy before.”

“Why would he send Lazare to swear fealty to King Charles?”

Chiang shrugged. “Doubtless to keep the man from your bed.”

She nearly choked on the irony of it. Lazare had taken care of that aspect of the marriage himself. And now that he was gone, she could not place him between herself and the English baron.

“Burgundy has left also?” asked Chiang.

“Aye, he claimed he had some private matter to attend to,” said Lianna glumly. “He had no right,” she repeated. She studied Chiang’s face, admiring his implacable concentration, the deep absorption with which he performed his task. His eyes, exotically upturned at the corners, seemed to hold the wisdom of centuries. He had a stark, regal face that put her in mind of emperors in the East, a distance too far to contemplate.

“You know he has it in his power to do most anything he wishes. Pass me that siphon, my lady.”

She handed him a copper tube. “That is what worries me about Uncle Jean. He also refused to send reinforcements to repel the English baron. He will not risk King Henry’s displeasure.”

Carefully Chiang extracted the purified salt from the vat. “Will the Englishman press his claim by force?”

“I know not. But we should be prepared.” She sat back on her heels and watched Chiang work, his short brown fingers handling scales and calipers with the delicacy of a surgeon. Sympathy, affection, and respect tumbled through her. Chiang had been a fixture at Bois-Long since the days of her youth. Like the man himself, his arrival was a mystery. Fleeing the capture of a mysterious ship from the East, he’d washed up on the Norman shore, the sole survivor of a vessel whose destination and mission Chiang had never revealed.

Only the Sire de Bois-Long, Lianna’s father, had protected the strange-looking man from a heathen’s death at the hands of superstitious French peasants. With his timeless knowledge of defense and his meticulous skill at gunnery, Chiang had repaid Aimery the Warrior a hundredfold.

But even now, the castle folk who had known him for years regarded him as an oddity, some gossips falling just short of denouncing him as a sorcerer. The men-at-arms begrudged him this small workroom in a corner of the armory and never failed to sketch the sign of the cross when passing by.

Chiang peered at her through wide-set, fathomless eyes. “And are you prepared, my lady?”

She hung her head. During the two days of the duke’s visit, she’d prayed and worried over a difficult decision. “Yes,” she said faintly.

He set aside his sieves and calipers and gave her the full measure of his attention. “Tell me.”

She tapped her chin with her forefinger. “I’ve sent a missive to Raoul, Sire de Gaucourt in Rouen, asking for fifty men-at-arms.”

“Did you consult Lazare in this?”

“Of course not. He knows nothing of diplomacy and politics. It matters not anymore. He is gone.”

Chiang showed no surprise at her defiance, yet she read disapproval in his calm, steady gaze. In appealing to the Sire de Gaucourt, she had betrayed her uncle. Gaucourt did not openly side with the Armagnacs, yet he was known to be sympathetic to Burgundy’s enemy.

“Was I wrong, Chiang?” she asked desperately.

He shrugged. His straight dark thatch of hair caught blue highlights from the coal fire. “You have shown yourself to be a poor judge of character, but Burgundy’s niece nonetheless. The duke himself would have done no less. Remember his tenet: ‘Power goes to the one bold enough to seize it.’”

Bolstered by Chiang’s counsel, she gave him a glimmer of a smile. “Very well. Shall we try the culverin?” The piece was new and had three chambers for more rapid firing.

He looked away. “I plan to do so. But alone.”

“What?”

“Your husband forbade me to work the guns with you.”

She leaped to her feet. “The salaud. How dare he dictate what I may and may not do?”

“Your laws dictate that you are subservient to your husband—or his son in his absence. Gervais has already said that he will enforce his father’s command.”

“We shall see,” she muttered, and left the armory to search for Gervais and tell him exactly what she thought of his father’s interdict.

In the hall she found the women at their spinning. Fleecy balls of carded wool littered the floor, and women’s talk wove in and out of the clack and whir of the spinning wheels. Edithe sat by the hearth, idly eating a pasty.

“What do you, Edithe?” Lianna asked, struggling to keep the irritation from her voice. “Why are you not helping with the spinning?”

The girl wiped her mouth on her sleeve. “Lazare released me,” she said, a faint gleam of smugness in her ripe smile.

Lianna stared. The wooden sounds of the wheels stopped, leaving an echo of expectant silence in the hall. Lazare had singled Edithe out to vent his lust; apparently all knew of it. Covering her dismay with anger, Lianna ordered the women back to work with a clipped imperative, then turned her attention to the idle maid.

Edithe made an elaborate show of finishing the pasty and licking the crumbs from her fingers. Fury welled like a hot powder charge within Lianna.

“I see,” she said, her throat taut as she exerted all the control she could marshal. “I wonder, Edithe, if you know where Lazare has gone.”

“Mayhap the mews,” the maid replied. “He does enjoy falconry, you know.”

No, Lianna didn’t know. Lazare had shared nothing of himself, and she had never asked. She didn’t care; she had his name, and that was all she needed for now. Still, his open infidelity stung her pride. With great satisfaction she said, “Lazare is no longer at Bois-Long, Edithe. He has gone to Paris.”

The maid’s eyes widened. Lianna smiled. “Lazare excused you from spinning. Very well, you are excused.” Edithe looked relieved until Lianna added, “You will do needlework instead. Aye, the chaplain needs a new alb.”

Edithe’s face crumpled in dismay. “But I am so clumsy with the needle,” she said.

“Doing boonwork for the church is good for the soul,” Lianna retorted, and strode out of the hall. Climbing the stairs to the upper chambers, she tried to formulate a speech scathing enough for Gervais. Keep her from her gunnery indeed. Her dudgeon peaked as she arrived at the room he shared with Macée. She raised her fist to knock.

A sound from within stopped her. A moan, as if someone were being tortured. Nom de Dieu, was Gervais beating his wife? But the next sound, a warm burble of laughter followed by a remark so ribald Lianna barely understood it, mocked that notion. Cheeks flaming, she fled.

Her fury deepened into an unfamiliar sense of helpless frustration. Shamed by the tears boiling behind her eyes, she rushed to the stables and commanded her ivory palfrey to be saddled. She rode away from the château at a furious gallop.

Please be there, she prayed silently as the greening landscape whipped by. Please be there.

Twice during her uncle’s sojourn she had managed to slip off to the place of Cuthbert’s cross; twice she’d found the coppice empty. No, not quite empty. The first time she’d found a single snowdrop lying on the cross, its waxy petals still fresh. The second time she’d found the emerald-tipped feather of a woodcock. She kept the flower and feather in her apron pocket, and often her fingers stole inside to touch the evidence that Rand had gone seeking her. Evidence that he wasn’t just a dream conjured by her troubled mind. Evidence that one man found her desirable.

But today a token would not suffice. Encased by the icy armor of betrayal and confusion, she needed Rand—his generous strength, his tender smile, the liquid velvet of his voice. She needed to gaze into the same green depths of his eyes.

He was there.

Lianna checked her horse, dismounted, and tethered the palfrey to a bush where Charbu grazed. Rand sat leaning against the cross. His winsome smile reached across the distance that separated them, to beckon her.

Her heart lifting, she hesitated, then approached at a slow walk. The scene was almost too perfect for her worldly presence to disturb. Rand sat cross-legged, surrounded by an arch of trees and meadow grasses that nodded in the breeze. An errant shaft of sunlight filtered through the budding larch boughs, touching his golden hair with sparkling highlights. In his lap he held a harp. The fingers of one hand strummed idly over the strings. Stepping closer, she saw that his other hand cradled a baby rabbit. I nearly slew its mother, she thought absurdly.

Rand’s eyes never left her. At last he spoke—to the rabbit, not to Lianna. “Off with you, nestling,” he said, and set the creature down, giving it a nudge with his finger until it scampered away. Then he laid aside his harp and stood.

She stayed rooted, frozen by new and awesome sensations that pulsated through her like the wingbeats of a lark. Rand was a deity in a dream garden, and suddenly she feared to enter his world. Lazare’s duplicity and her uncle’s scheming had soiled her. She couldn’t belong here.

But that was Belliane, an inner voice reminded her. To Rand she was Lianna, brave and unsullied in her anonymity.

He stepped forward, put out his hand, and brushed his knuckles lightly over her cold cheek, an inquiring gesture, one that demanded a response.

The restrained tenderness and gentle warmth of his touch melted the ice encasing Lianna. Thawed by his kindness, a single tear emerged, dangled on the points of her lashes, then coursed down her cheek. He traced its path with his thumb, caught the second with his lips, and then the broad wall of his chest absorbed the hot floodtide that followed.