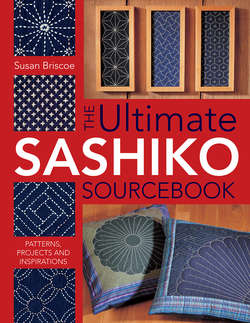

Читать книгу The Ultimate Sashiko Sourcebook - Susan Briscoe - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Blue and white, white and blue

ОглавлениеTraditional sashiko was usually indigo and white. This characteristic look was a response to Edo era sumptuary laws which prohibited the lower classes from wearing brightly coloured clothing and large patterns. Commoners could use indigo, so old indigo cloth was available in the home. The colour is still appreciated for its beauty. Polygonum tinctorium, Japanese indigo, can be grown to make an affordable dye. Fabric woven at home and recycled fabrics were sent to skilled professionals for dyeing. Synthetic indigo was introduced in the late 19th century and consequently there are few traditional dye shops in Japan today.

Indigo and white kogin (from koginu or work wear) and multicoloured Nanbu hishizashi (Nanbu diamond stitch) are two counted embroidery techniques from Aomori Prefecture which evolved from hitomezashi stitches, like the example from Shonai, Yamagata Prefecture (third picture above). As kogin and Nanbu hishizashi are like pattern darning, they are stitched on very coarsely woven cloth and cannot easily be combined with other sashiko. Patterns are not, therefore, included in this book, although a similar embroidered effect could be obtained by stitching hitomezashi on Aida or evenweave embroidery fabric (see pictures top of page 18).

CHIEKO HORI

Late Meiji Era Shōnai sashiko sorihikihappi (sled-hauling waistcoat), with protective shoulder patch in hishizashi (diamond stitch, page 105) and mukaichiyōzashi (facing butterfly stitch, page 108). Many Shōnai patterns have horizontal stitches only, with more thread on the back of the work than the front, giving extra insulation for winter wear. Some women used the thick warp threads to help align their stitches.

COLLECTION OF CHIE IKEDA, YONESHIMA, SAKATA-SHI

Some unusual pieces of Shōnai sashiko show the influence of textiles made by the Ainu (the indigenous people of Hokkaido), with curved border patterns in chain stitch (see the cushions on page 36). Like Ainu clothing, sashiko on clothes was symmetrical, with more decorative or dense patterns at shoulders, the front openings or cuffs. The Ainu believed these areas needed special protection because they were vulnerable to evil spirits entering the body.

AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

Indigo and white colour combinations give sashiko a strong tonal contrast. Migration of indigo from fabric to thread often tinted old sashiko stitching pale ice blue. Blue on blue was also common. Indigo strengthens fibres and the residual smell of fermented indigo and ammonia in the dye was believed to repel snakes and insects.

Cotton has been grown commercially in Japan since the 1600s, first as a luxury fibre, and by the early 19th century it was widely cultivated south of the Aizu region. Patterned cotton fabrics were used for sashiko in some areas. Kasuri (ikat), katazome (stencilled) or shibori (tie-dyed) cloth were popular in Aomori Prefecture, while shima (striped) cotton was used for fishermen’s coats in Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures on the Pacific coast.

Sashiko hanten jackets typify fishermen’s traditional clothes, as shown by this ceramic Hakata ningyo (doll) figurine, made in Kyushu, Japan in the 1950s. A simple pattern of triangles, like the first step of asanoha (hemp leaf, page 72), is painted stitch-by-stitch across the jacket’s shoulders. Hakata ningyo are noted for their detailed and acurate costume decoration. Even without his net, this fisherman’s profession can be identified by his clothing.

AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

Woven patterns could be used to help align sashiko stitches or be completely disregarded, as in this Taisho era furoshiki (wrapping cloth) from Shikkoku. Tie it to show the corner fan or the variation on shippō tsunagi (page 64). Shima (checks) are less common than stripes.

AUTHOR’S COLLECTION