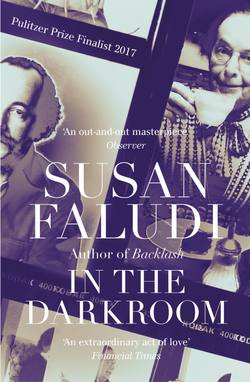

Читать книгу In the Darkroom - Susan Faludi, Susan Faludi - Страница 10

1 Returns and Departures

ОглавлениеOne afternoon I was working in my study at home in Portland, Oregon, boxing up notes from a previous writing endeavor, a book about masculinity. On the wall in front of me hung a framed black-and-white photograph I’d recently purchased, of an ex-GI named Malcolm Hartwell. The photo had been part of an exhibit on the theme “What Is It to Be a Man?” The subjects were invited to compose visual answers and write an accompanying statement. Hartwell, a burly man in construction boots and sweat pants, had stretched out in front of his Dodge Aspen in a cheesecake pose, a gloved hand on a bulky hip, his legs crossed, one ankle over the other. His handwritten caption, appended with charming misspellings intact, read, “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.” I took a break from the boxes to check my e-mail, and found a new message:

To: Susan C. Faludi

Date: 7/7/2004

Subject: Changes.

The e-mail was from my father.

“Dear Susan,” it began, “I’ve got some interesting news for you. I have decided that I have had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that I have never been inside.”

The announcement wasn’t entirely a surprise; I wasn’t the only person my father had contacted with news of a rebirth. Another family member, who hadn’t seen my father in years, had recently gotten a call filled with ramblings about a hospital stay, a visit to Thailand. The call was preceded by an out-of-the-blue e-mail with an attachment, a photograph of my father framed in the fork of a tree, wearing a pale blue short-sleeved shirt that looked more like a blouse. It had a discreet flounce at the neckline. The photo was captioned “Stefánie.” My father’s follow-up phone message was succinct: “Stefánie is real now.”

The e-mail notifying me was similarly terse. One thing hadn’t changed: my photographer father still preferred the image to the written word. Attached to the message was a series of snapshots.

In the first, my father is standing in a hospital lobby in a sheer sleeveless blouse and red skirt, beside (as her annotation put it) “the other post-op girls,” two patients who were also making what she called “The Change.” A uniformed Thai nurse holds my father’s elbow. The caption read, “I look tired after the surgery.” The other shots were taken before the “op.” In one, my father is perched amid a copse of trees, modeling a henna wig with bangs and that same pale blue blouse with the ruffled neckline. The caption read, “Stefánie in Vienna garden.” It is the garden of the imperial villa of an Austro-Hungarian empress. My father was long a fan of Mitteleuropean royals, in particular Empress Elisabeth—or “Sisi”—Emperor Franz Josef’s wife, who was known as the “guardian angel of Hungary.” In a third image, my father wears a platinum blond wig—shoulder length with a ’50s flip—a white ruffled blouse, another red skirt with a pattern of white lilies, and white heeled sandals that display polished toenails. In the final shot, titled “On hike in Austria,” my father stands before her VW camper in mountaineering boots, denim skirt, and a pageboy wig, a polka-dotted scarf arranged at the neck. The pose: a hand on a jutted hip, panty-hosed legs crossed, one ankle before the other. I looked up at the photo on my wall. “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.”

The e-mail was signed, “Love from your parent, Stefánie.” It was the first communication I’d received from my “parent” in years.

My father and I had barely spoken in a quarter century. As a child I had resented and, later, feared him, and when I was a teenager he had left the family—or rather been forced to leave, by my mother and by the police, after a season of escalating violence. Despite our long alienation, I thought I understood enough of my father’s character to have had some inkling of an inclination this profound. I had none.

As a child, when we had lived together in a “Colonial” tract house in the suburban town of Yorktown Heights, an hour’s drive north of Manhattan, I’d always known my father to assert the male prerogative. He had seemed invested—insistently, inflexibly, and, in the last year of our family life, bloodily—in being the household despot. We ate what he wanted to eat, traveled where he wanted to go, wore what he wanted us to wear. Domestic decisions, large and small, had first to meet his approval. One evening, when my mother proposed taking a part-time job at the local newspaper, he’d made his phallocratic views especially clear: he’d swept the dinner dishes to the floor. “No!” he shouted, slamming his fists on the table. “No job!” For as far back as I could remember, he had presided as imperious patriarch, overbearing and autocratic, even as he remained a cipher, cryptic to everyone around him.

I also knew him as the rugged outdoorsman, despite his slender build: mountaineer, rock climber, ice climber, sailor, horseback rider, long-distance cyclist. With the costumes to match: Alpenstock, Bavarian hiking knickers, Alpine balaclava, climber’s harness, yachter’s cap, English riding chaps. In so many of these pursuits, I was his accompanist, an increasingly begrudging one as I approached adolescence—second mate to his captain on the Klepper sailboat he built from a kit, belaying partner on his weekend assays of the Shawangunk cliffs, second cyclist on his cross-the-Alps biking tours, tent-pitching assistant on his Adirondack bivouacs.

All of which required vast numbers of hours of training, traveling, sharing close quarters. Yet my memory of these ventures is nearly a blank. What did we talk about on the long winter evenings, once the tent was raised, the firewood collected, the tinned provisions pried open with the Swiss Army knife my father always carried in his pocket? Was I suppressing all those father-daughter tête-à-têtes, or did they just not happen? Year after year, from Lake Mohonk to Lake Lugano, from the Appalachians to Zermatt, we tacked and backpacked, rappelled and pedaled. Yet in all that time I can’t say he ever showed himself to me. He seemed to be permanently undercover, behind a wall of his own construction, watching from behind that one-way mirror in his head. It was not, at least to a teenager craving privacy, a friendly surveillance. I sometimes regarded him as a spy, intent on blending into our domestic circle, prepared to do whatever it took to evade detection. For all of his aggressive domination, he remained somehow invisible. “It’s like he never lived here,” my mother said to me on the day after the night he left our house for good, twenty years into their marriage.

When I was fourteen, two years before my parents’ separation, I joined the junior varsity track team. Girls’ sports in 1973 was a faintly ridiculous notion, and the high school track coach, who was first and foremost the coach of the boys’ team, mostly ignored his distaff charges. I designed my own training regimen, leaving the house before dawn and loping the side streets to Mohansic State Park, a manicured recreation area that used to be the grounds for a state insane asylum, where I ran a long circuit around the landscaped terrain, alone. By then, I had developed a preference for solo sports.

Early one August morning I was lacing my sneakers in the front hall when I sensed a subtle atmospheric change, like the drop in barometric pressure as a cold front approaches or the prodromal thrumming before a migraine, which signaled to my aggrieved adolescent mind the arrival of my father. I reluctantly turned and made out his pale, thin frame emerging from the gloom at the bend of the stairs. He was wearing jogging shorts and tennis sneakers.

He paused on the last step and inspected the situation with his peculiar remove, as if peering through a keyhole. After a while, he said, “I am running also,” his thick Hungarian accent stretching out the first syllable, “aaaalso.” It was an insistence, not an offer. I didn’t want company. A bit of doggerel, picked up who knows where, spooled in my head.

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away …

I pushed through the screen door, my father shadowing my heels. The air was fat with humidity. Tar bubbles blistered the blacktop. I poked them with the toe of one sneaker while my father deliberated, turning first to his old VW camper, then to the lime-green Fiat convertible he had recently purchased, used, “for your mother.” My mother didn’t drive. “Waaall,” he said after a while. “We’ll take the Fiat.”

We drove the five-minute route in silence. He wheeled into the lot of the IBM Research Center, a block from our destination. Prominent signs made clear that parking was for employees only. My father paid them no mind. He took a certain pride in pulling off small scams, which he called “getting awaaay with things,” a predilection that led him to swap price tags on items at the local shopping center. He acquired a camping cooker in this manner, at a savings of $25.

“Did you lock your door?” my father asked as we headed across the lot, and, when I said I had, he looked at me doubtfully, then turned and went back to check. The flip side of my father’s petty transgressions was an obsession with security.

We hoofed it down the treeless corporate drive to Route 202, the thoroughfare that runs along the north edge of the park. We dodged between speeding cars to the far side, and climbed over the metal divider, jumping down into the depression beyond it. My father paused. “It happened there,” he said. He often talked this way, without antecedents, as if mid-conversation, a conversation with himself. I understood what “it” was: some months earlier, after midnight, teenagers returning from a party had run the stop sign on Strang Boulevard and collided with another car. Both vehicles had hurtled over the divider and landed on their roofs. No one survived. A passenger was decapitated. My father had been witness not to the accident itself but to its immediate aftermath. He was on call that night with the Yorktown Heights Ambulance Corps.

My father’s eagerness to volunteer for the local emergency medical service had seemed out of character, at least the character I thought I knew. He shrank from community affairs, from social encounters in general. On the occasions when my parents had guests, my father would either sit mum in his armchair or take cover behind his slide projector, working his way through tray after tray of Kodachrome transparencies of our hiking expeditions, naming each and every mountain peak in each and every frame, recounting every twist and turn in the trail, until our visitors, wild with boredom, fled into the night.

He referred to his service with the ambulance corps as “my job saaaaving people.” Which I also didn’t understand. Our town was a place of non-events, the 911 summons a suburban emergency: a treed cat, a housewife having an anxiety attack, an occasional kitchen-stove fire. The crash in Mohansic State Park was an exception, although again there was no one to save. When my father arrived, the police were covering the bodies. The ambulance driver grabbed his arm. “Steve, don’t look,” my father recalled him saying. “You don’t want that in your memory.” The driver had no way of knowing the wreckage already lodged in my father’s memory, and of how hard he had worked to erase it.

Leaving the old accident site behind, the two of us took off running along the paved road and into the picnic area, past rows of empty parking lots. The route began on a dull flat stretch of baseball diamonds and basketball courts, then looped around the giant public pool (where I worked summers at the snack stand) and along Mohansic Lake, finishing up a long hill. By the lake, we picked up a narrow footpath. We ran without speaking, single file.

At the final climb, the path gave way to wider pavement, and we began jogging side by side. Minutes into the ascent, he picked up his pace. I sped up. He ran faster. So did I. He pulled ahead again, then I did. We both gasped for breath. I looked over at him, but he didn’t return my gaze. His skin was scarlet, shiny with sweat. He stared straight ahead, intent on an invisible finish line. All the way up the hill, the fierce mute maneuvering maintained. When the pavement flattened, I ached to ease the pace. My stomach was heaving and my vision had blurred. My father broke into a furious stride. I tried to match it. It was, after all, the early ’70s; “I Am Woman (Hear Me Roar)” played on the mental sound track of my morning jogs. But neither my ardor for women’s lib nor my youth nor all my training could compete with his determination.

Something about my father became palpable in that moment, but what? Was I witnessing raw aggression or a performance of it? Was he competing with his daughter or outracing someone, or something, else? These weren’t questions I’d have formulated that morning. At the time, I was trying not to retch. But I remember the thought, troubling to my budding feminism, that flickered through my mind in the final minutes of the run: It’s easier to be a woman. And with it, I let my legs slow. My father’s back receded down the road.

At home in those years, my father was a paragon of the Popular Mechanics weekend man, always laboring on his latest home craft project: a stereo and entertainment cabinet, a floor-to-ceiling shelving system, a dog house and pen (for Jání, our Hungarian vizsla), a shortwave radio, a jungle gym, a “Japanese” goldfish pond with recycling fountain. After dinner he would absent himself from our living quarters—our suburban tract home had one of those living-dining open-floor plans, designed for minimal privacy—and descend the steps to his Black & Decker workshop in the basement. I did my homework in the room directly above, feeling through the floorboards the vibration of his DeWalt radial arm saw slicing through lumber. On occasion, he’d invite me to assist in his efforts. Together we assembled an educational anatomy model that was popular at the time: “The Visible Woman.” Her clear plastic body came with removable parts, a complete skeleton, “all vital organs,” and a plastic display stand. For much of my childhood she stood in my bedroom—on the vanity dresser that my father also built, a metal base with a wood-planked top, over which he’d staple-gunned a frilled fabric with a rosebud pattern.

From his domain in the basement, my father designed the stage sets he desired for his family. There was the sewing-machine table with a retractable top he built for my mother (who didn’t like to sew). There was the to-scale train set that filled most of a room (its Nordic landscape elaborately detailed with half-timbered cottages, shops, churches, inns, and villagers toting groceries and hanging laundry on a filament clothesline) and the fully accessorized Mobil filling station (hand-painted Pegasus sign, auto repair lift, working garage doors, tiny Coke machine). His two children played with them with caution; a broken part could be grounds for a tirade. And then there was one of my father’s more extravagant creations, a marionette theater—a triptych construction with red curtains that opened and closed with pulleys and ropes, two built-in marquees to announce the latest production, and a backstage elevated bridge upon which the puppeteer paced the boards and pulled the strings, unseen. This was for me. My father and I painted the storybook backdrops on large sheets of canvas. He chose the scenes: a dark forest, a cottage in a clearing surrounded by a crumbling stone wall, the shadowy interior of a bedroom. And he chose the cast (wooden Pelham marionettes from FAO Schwarz): Hunter, Wolf, Grandmother, Little Red Riding Hood. I put on shows for my brother and, for a penny a ticket, neighborhood children. If my father ever attended a performance, I don’t remember it.

“Visiting family?” my seatmate asked. We were in an airplane crossing the Alps. He was a florid midwestern retiree on his way with his wife to a cruise on the Danube. My assent prompted the inevitable follow-up. While I deliberated how to answer, I studied the overhead monitor, where the Malév Air entertainment system was playing animated shorts for the brief second leg of the flight, from Frankfurt to Budapest. Bugs Bunny sashayed across the screen in a bikini and heels, befuddling a slack-jawed Elmer Fudd.

“A relative,” I said. With a pronoun to be determined, I thought.

In September 2004, I boarded a plane to Hungary. It was my first visit since my father had moved there a decade and a half earlier. After the fall of Communism in 1989, Steven Faludi had declared his repatriation and returned to the country of his birth, abandoning the life he had built in the United States since the mid-’50s.

“How nice,” the retiree in 16B said after a while. “How nice to know someone in the country.”

Know? The person I was going to see was a phantom out of a remote past. I was largely ignorant of the life my father had led since my parents’ divorce in 1977, when he’d moved to a loft in Manhattan that doubled as his commercial photo studio. In the subsequent two and a half decades, I’d seen him only occasionally, once at a graduation, again at a family wedding, and once when my father was passing through the West Coast, where I was living at the time. The encounters were brief, and in each instance he was behind a viewfinder, a camera affixed to his eye. A frustrated filmmaker who had spent most of his professional life working in darkrooms, my father was intent on capturing what he called “family pictures,” of the family he no longer had. When my boyfriend had asked him to put the camcorder down while we were eating dinner, my father blew up, then retreated into smoldering silence. It seemed to me that was how he’d always been, a simultaneously inscrutable and volatile presence, a black box and a detonator, distant and intrusive by turns.

Could his psychological tempests have been protests against a miscast existence, a life led severely out of alignment with her inner being, with the very fundaments of her identity? “This could be a breakthrough,” a friend suggested, a few weeks before I boarded the plane. “Finally you get to see the real Steven.” Whatever that meant: I’d never been clear what it meant to have an “identity,” real or otherwise.

In Malév’s economy cabin, the TV monitors had moved on to a Looney Tunes twist on Little Red Riding Hood. The wolf had disguised himself as the Good Fairy, in pink tutu, toe shoes, and chiffon wings. Suspended from a wire hanging off a treetop, he flapped his angel wings and pretended to fly, luring Red Riding Hood out on a limb to take a closer look. Her branch began to crack, and then the entire top half of the tree came crashing down, hurtling the wolf in drag into a heap of chiffon on the ground. I watched with a nameless unease. Was I afraid of how changed I’d find my father? Or of the possibility that she wouldn’t have changed at all, that he would still be there, skulking beneath the dress.

Grandmother, what big arms you have! All the better to hug you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big ears you have! All the better to hear you with, my dear.

Grandmother, what big teeth you have! All the better to eat you with, my dear!

And the Wicked Wolf ate Little Red Riding Hood all up …

Malév Air #521 landed right on time at Budapest Ferihegy International Airport. As I dawdled by the baggage carousel, listening to the impenetrable language (my father had never spoken Hungarian at home, and I had never learned it), I considered whether my father’s recent life represented a return or a departure. He had come back here, after more than four decades, to his birthplace—only to have an irreversible surgery that denied a basic fact of that birth. In the first instance, he seemed to be heeding the call of an old identity that, no matter how hard he’d run, he’d failed to leave behind. In the second, she’d devised a new one, of her own choice or discovery.

I rolled my suitcase through the nothing-to-declare exit and toward the arrivals hall where “a relative,” of uncertain relation to me, and maybe to herself, was waiting.