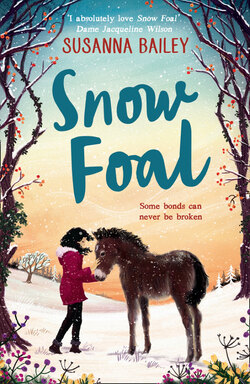

Читать книгу Snow Foal - Susanna Bailey - Страница 10

Оглавление

Addie crawled to the end of her bed and pulled one of the curtains aside. She leaned a hand against the windowpane, tried to see outside. It left its shape there when she moved, a ghost hand among stars of frost on the cold glass.

It wasn’t really morning yet. Just fingers of pale light in the yard below. But Addie could see that more snow had fallen overnight. Much more. Not the sleety mess that fell in the town, slippery and slimy in the streets, grey and dirty in the gutters. Proper snow. Snow you could build things with. Perfect snow, glistening silvery white as far as Addie could see: like the snow in the paintings Mam did. Before.

Would the snow stop Penny coming back for her? Ruth had said something about the difficult roads near the farm. Addie closed the curtain again and got down from her bed. Pretty as it was, it had better stop falling soon.

She found yesterday’s jeans and jumper on the chair by her bed, and put them on over her pyjamas. She tiptoed past Sunni’s bed, the wooden floor smooth and cold under her bare feet.

One of the floorboards near the door creaked as Addie stepped on it. Sunni stirred, flung one arm out of her covers and over the edge of the bed. There was a gentle clinking sound. Addie stood still. She held her breath. She waited. Watched. Something sparkled on Sunni’s wrist: she was still wearing her bracelets.

Sunni didn’t move again, so Addie edged out of the room and along the dim landing in the direction she remembered the bathroom to be. Her heart pounded as she passed two closed doors on her right-hand side. Which was Ruth and Sam’s room? Addie couldn’t remember.

Would they mind that she was up?

The door next to the bathroom was partly open, blue light spilling from inside on to the floor in front of Addie. The bathroom was on the other side of it, so Addie would have to go past to get a drink. She glanced inside the room as she did so, fingers crossed behind her back. A small child was sitting bolt upright in bed, pale hair gleaming like a halo in the watery blue light. He or she, Addie couldn’t tell, was staring straight at her.

Addie stared back as she passed, willing whoever it was to keep quiet. They did.

There was a stack of coloured plastic cups by the bathroom sink. Addie filled a green one with water from the tap. It tasted different from the water at home. Cleaner. Nicer. She drained the cup, filled it again. She could take it back to her room.

When she passed the open door again, the child was huddled under the bedclothes. Addie heard soft, thin sounds, like a kitten crying for its mother.

Sunni had switched on the light and was sitting up in bed, brushing her hair. She gave Addie a small, quick smile. Perhaps she didn’t mind that Addie had woken her. Addie tried to smile back, but her mouth felt stiff. Should she tell Sunni about the child? Would whoever it was want anyone to know they were upset? Maybe not. She drank her water, wondered what to do next.

A door slammed downstairs. Somebody whistled in the yard outside the window. Someone else was up then.

‘That’s Gabe,’ Sunni said, straightening her bed covers. ‘And Flo. They’re off to see to the cows.’

Addie stared at her. ‘In the dark?’

Sunni rolled her eyes, as if Addie had said something really stupid.

‘Who’s Gabe?’ Addie said quickly.

‘Ruth and Sam’s son. He’s fourteen. He’s got a guitar and he lets me play it.’ She looked at Addie, stared into her eyes. ‘I’m the only one that’s allowed.’

Addie turned away. She peeped out through the curtains again. She couldn’t see anyone. She still couldn’t see much at all, except the snow, and patches of orange light from two downstairs windows.

‘Is Flo Gabe’s sister, then?’ she asked.

‘She’s a sheepdog,’ said Sunni, shoving her feet into fleecy slippers. ‘She goes everywhere with Gabe. She’s a bit bonkers. Like him.’ She pulled a scarlet dressing gown round her shoulders. She looked Addie up and down. ‘We don’t get dressed for breakfast,’ she said. ‘We go down in our nightclothes.’

‘I don’t,’ said Addie. ‘Except at home.’

‘Well, this is a foster home. It’s the same.’

Addie shook her head. ‘It isn’t. And anyway, my social worker’s coming back this morning. Early. So I’m ready. And I’m not having breakfast.’

‘She’s not taking you home, if that’s what you think,’ Sunni said. ‘And you have to have breakfast. That’s the rule. Come on . . . before Jude eats all the toast.’ Sunni flounced to the door, her dressing gown floating behind her like a cape. ‘Oh, and that’s Jude’s cup you’ve got there,’ she said over her shoulder. ‘He’ll go nuts.’

Was Jude the child in the other bedroom? Addie didn’t like the sound of him. She put the green cup down on Sunni’s shelf, among her collection of elephants. ‘Wait a minute,’ she shouted, ‘I’ve got bare feet.’

But Sunni was gone.

Addie’s feet were freezing. She looked around for the bag Penny had made her pack. Her favourite socks were in there. The rainbow ones Mam chose.

The bag was at the foot of the bed. It was empty. Where were her things?

‘Addie, sweetheart. Good morning! I wondered if it was you I heard up and about just now.’ Ruth was in the doorway, wiping her hands on her apron. Addie turned away, pretended to search in the front pocket of her bag.

Ruth perched on the end of Sunni’s bed. ‘I put your clean things in the drawers for you, love. The ones with the blue handles. Breakfast’s ready, so pop something on your feet and we’ll go down together, shall we?’

Addie’s fists tightened. ‘I like my things in my bag,’ she said.

‘That’s OK, Addie. Put them back for now then. I understand.’

It wasn’t OK. Nothing was. And Ruth didn’t understand anything. Addie pulled on her trainers. She would do without socks.

And she would do without Ruth’s breakfast. Whatever the stupid rule was.