Читать книгу The Goodbye Quilt - Сьюзен Виггс, Susan Wiggs - Страница 12

Chapter Three

Оглавление“Remember this one?” I ask, angling part of the quilt into Molly’s line of vision.

“I guess.”

“I bet you don’t remember it.”

“Then why did you ask? You always do that, Mom.”

“Do I? I never noticed.”

“You’re always quizzing me about stuff you think should be important to me.”

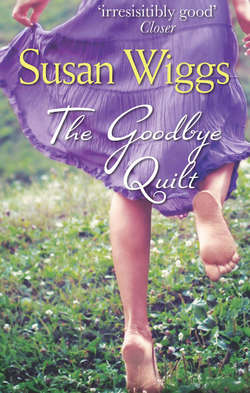

“Really? Yikes.” I brush my hand over the piece of purple cotton, covered by lace.

“So what about that one?” She is instantly suspicious. All summer long, little “do-you-remembers” and “last times” have sneaked in—the last time we drove to the lake at the county line to set off fireworks, the last time Dan and I attended one of her piano recitals, the last time she went for a haircut at the Twirl & Curl.

“It’s from a dress your father bought you,” I say, needle pushing in and out, running a line of stitches to spell out Daddy’s girl.

“Dad bought me a dress? No way.”

“He did, at the Mexican Marketplace. I can’t believe you forgot.”

“Mom. What was I, three or four years old?”

“Four, I think.”

“I rest my case.”

In my mind’s eye, I can still see her turning in front of the hall mirror, showing off the absurd confection of purple cotton and cheap lace. “It swirls,” Molly had shouted, spinning madly. “It swirls!” I was less charmed when she insisted on wearing it to church for the next nine weeks. The dress fell apart years ago, but there was enough fabric left to work into the quilt.

Memories flow past in a swift smear of color, like the warehouses and billboards lining the interstate. When I shut my eyes, I can picture so many moments, frozen in time. So many details, sharp as a captured image—the wisp of my newborn baby’s hair, the sweet curve of her cheek as she nurses. I can still imagine the drape of her christening gown, which is wrapped in tissue now, stored in the bottom of the painted cedar chest in the guestroom. I can clearly see myself poking a spoonful of white cereal into a round little birdlike mouth. I see Molly spring forward on chubby legs off the side of the pool, into my outstretched arms.

All those firsts. The first day of kindergarten: Molly wore her hair in two tight pigtails, her plaid jumper ironed in crisp pleats, her backpack filled with waxy-smelling new crayons, sharpened pencils, lined paper, a lunch I’d spent forty-five minutes preparing.

“Do you remember your first day of school?” I ask her now, flourishing the part of the quilt made of the uniform blouse.

“Sure. My teacher was Miss Robinson, and I carried a Mulan lunch box.” Molly changes lanes and eases past a poky hybrid car. “You put a note in my lunch. I always liked it when you did that.”

I don’t recall the teacher or the lunch box, but I definitely remember the note, the first of many I would tuck into Molly’s lunch over the years. I always tried to write a few words on a paper napkin with a little smiling cartoon mommy, with squiggles to represent my hair, and the message “I LOVE.png U. Love, Mommy.”

I tried to upgrade my wardrobe for the occasion, wearing slacks, Weejuns and coral lip gloss from a department store counter. I felt important, compelled by mission and duty, as Molly chattered gleefully in the back of my station wagon.

Stopping at the tree-shaded curb of the school, I pretended to be calm and cheerful as I kissed Molly’s cheek, stroked her head and then smilingly waved goodbye. She met up with her friends Amber and Rani. The girls went inside together, giggling and skipping the whole way, into the redbrick institution that suddenly looked huge and forbidding to me.

There was a New Mothers’ coffee in the library. At the meeting, we moms worked out party plans and carpool arrangements with the sober attention of battle commanders. I felt secretly intimidated—not by the working moms in their power suits and high heels. On some level I understood they were as scared and uncertain as I was, even with their advanced degrees and job titles.

No, I was overawed by the stay-at-home moms. They were the gold standard we all aspired to. They seemed so organized and poised, in khakis with earth-tone sweaters looped negligently over their shoulders, datebooks open in front of them, monogrammed pens poised to make notes. Independent yet obviously supported by the unseen infrastructure of husbands and homeowners’ associations, they were eminently comfortable in their own skin.

To this day, I don’t remember driving home after handing my child over to a new phase of life. All I remember is bursting into the house, sitting down at the breakfast counter with the view of the jungle gym Dan had built in the backyard, and shaking with a sense of emptiness I hadn’t expected to feel. Even Hoover, huddled in confusion at my feet, couldn’t cheer me up. But back then, hope had glimmered at the end of the day. Molly would come home, she’d eat pecan sandies and drink a glass of milk while chattering on about kindergarten, and all would be well.

Although years have passed since that bright August morning, I never quite mastered the put-together look or the air of confidence I observed in my peers. I didn’t really fit in with the stay-at-homes, but I wasn’t a career woman, either. A scattershot woman, you might call me, aiming myself in different directions, my only true calling that of loving my family.

I kept meaning to find something—a vocation, a passion, a marketable way to spend my time. But after Molly was born, the quest simply didn’t seem to matter so much. Unconcerned with a career trajectory, I bounced around to a few different jobs, never quite finding the right fit. This didn’t bother me, because without really planning it, I had lucked into a life I loved so much I never wanted it to change. The quilt shop became my second home. I loved the creative energy of the shop, the dry smell of the fabric, the crisp metallic bite of my super-sharp scissors on the cutting table. Working at Minerva’s shop became more than a part-time job during the school year. It was a place of refuge from the empty hours of the school day.

Molly glances over; I see her watching my busy hands.

“What?” I ask.

“Did you know Athena is the goddess of quilting?”

“She’s the Warrior Woman,” I correct her. “It’s one of the few things I remember from mythology.”

“Most people don’t know she’s also the goddess of arts and crafts,” Molly says, full of authority, the way she gets sometimes. “Domestic crafts require planning and strategy, too. That’s how the logic goes, anyway.”

“Athena was superwoman, then. Waging war and weaving baskets.” I settle back with the quilt draped over my lap and try to focus on feeling like a goddess. My stitches meander into overlapping spirals. These will be a reminder of the cyclical nature of families, the comings and goings of generations. They say a child leaves home in phases. She is weaned: Molly weaned herself as soon as she learned to walk, preferring a binky she could carry around in her pocket. Then she starts school. Goes on her first sleepover. To sleep-away camp. A field trip to the state capitol. She learns to drive, and each time she heads out the door, it takes her out of reach, on her own. This is simply the next step in the process. She’ll be fine. I’ll be fine.

I swear.

“I spotted an A,” Molly says abruptly, bringing me back to the present. “The Aladdin Motel. And there’s a B—Uncle Porky’s Burger Barn….”

The hunt is on—an old alphabet game we used to play on long car trips. We quickly find our way through to the letter J, calling out names of towns and cafés, cribbed from highway signs, billboards and truck stops. The town of Jasper keeps the game moving. The Q is found on a hand-lettered roadside “Bar-B-Q,” and we are grateful for colloquial spelling habits. We never get stuck on X, thanks to the freeway exit signs, and Z is found on a radio station billboard, KIZZ: Downhome Country for Uptown Folks.

In a Big Boy restaurant in Franklin, a young mother is trying to work the newspaper Sudoku puzzle while her toddler, strapped into a little wooden high chair, makes monkeyshines to get her attention. He leans as far sideways as the high chair permits, makes a sound like a cat, bangs his fork on the table, crams dry Cheerios into his mouth and uses a chicken nugget to smear ketchup on his tray like a baby Jackson Pollock. The young mother tucks her hair behind her ear and fills in another blank space on the puzzle.

I want to rush across the dining room and shake the woman. Can’t you see he needs you to look at him? Play with him, will you, already? It’ll be over before you know it.

It’s easy to recognize a little of myself in the weary, distracted young mother. I used to be like her—preoccupied with matters of no importance, never seeing the secretive, invisible passage of time slip by until it was gone. Yet if someone had deigned to point this out, I would have been baffled, maybe even indignant. Disregard my child? What do you take me for?

However, when you’re with a toddler who takes forty-five minutes to eat a chicken nugget, the moments drag. Or when your baby has the croup at 3:00 a.m. and you’re sitting in the bathroom with the steam on full blast, crying right along with her because you’re both so tired and miserable—those nights seem to have no end.

From my perspective at the other end of childhood, I want to tell the young mother what I know now—that when a child is little, the days roll by at a leaden pace, blurring together. You’re like a cartoon character, blithely oblivious while crossing a precarious wooden bridge, never knowing it’s on fire behind you, burning away as you go. Sure, everybody says to enjoy your kids while they’re little, because they’ll be grown before you know it, but nobody ever really believes it. The woman at the next table simply wouldn’t see the bridge, see time eating up the moments like a fire-breathing dragon.

Fortunately for everyone involved, even I’m not crazy enough to intrude. For all I know, she’s got a load of worries on her mind, or maybe she just needs ten minutes to dream her own dreams. Maybe she craves the neat, precise order of a Sudoku puzzle as a reminder that everything has a solution. By the time she finishes her puzzle, the kid has given up on her and finished his Cheerios and nugget. She wipes his face and hands, scoops him up and plants a perfunctory kiss on his head as she goes to the register.

Molly has missed the exchange entirely. She is absorbed in paging through the college’s glossy catalog. The booklet depicts an idyllic world where the grass is preternaturally green and weedless, buildings stand the test of time and students are eternally young, sitting around in earnest groups or laughing together over lattes. Professors look appropriately smart, many of them cultivating a kind of bohemian quirkiness that, in our hometown, would probably cause them to fall under suspicion.

“See anything you like?” I ask as she pauses on a page of course descriptions.

“Everything,” she states, her eyes dancing. “There’s a whole course called ‘Special Topics in Women’s Suffrage Music.’ And ‘Transgender Native American Art.’ ‘The Progressive Pottery Experience: Ideas in Transition.”’“ She struggles to keep a straight face. “I want it all.”

We have a laugh, and I can feel her excitement. The catalog is a treasure trove of possibilities, new things for her to learn, ways to think, ideas about life, maybe even a way to change the world.

Though I’m thrilled for her, I feel a silly twinge of envy. There are matters Dan and I can’t begin to teach her, I remind myself. That’s what college is for.

“I have no clue how I’m going to pick,” she says, her hand smoothing the pages.

“I wouldn’t know where to begin.” The admission masks an old ambivalence. I had always meant to finish college and even had a plan. For many people, this didn’t seem particularly bold, but in my family, it was a big step. Neither of my parents had gone to college; their own parents were immigrants and higher education was simply out of reach for them. My folks regarded college as an unnecessary frill, an expensive four-year procrastination before you get to the real part of life.

My dad worked as a shift supervisor at the tile plant. My mom stayed home with us and ironed. Really, she did. She took in ironing. We saw nothing unusual about this. There was never any shame, no judgment. It was who we were, and we were perfectly happy together. The house often smelled of the dry warmth of a heated iron and spray starch. There was a little rate sheet posted behind the kitchen door. People would leave their stuff in a basket by the milk box on the back stoop in the morning; Mom would iron it and the next day, my big brother Jonas would deliver the items—crisply pressed dress shirts and knife-pleated slacks for the plant executives, party dresses and St. Cecilia’s uniform blouses for their wives and kids.

I never really thought about what went through my mom’s mind as she stood at the ironing board, perfecting the details of other people’s clothing while Dire Straits played on the radio. Now I wonder if she was hot. Uncomfortable. Resigned. Or maybe she liked ironing and the work made her happy.

I wish I’d asked her. I wish she was still around, so I could ask her now.

Instead, eager for my independence, I planned my future. My dreams were nurtured by hours and hours in the library, reading books about women who created amazing lives for themselves, studying music and painting, science and business. I swore one day when I was a mother, I would instill these dreams in my children. I would be the mother I wanted my mother to be. And so I made a plan.

After high school, I would spend the summer working to save up money for tuition. Both my parents shook their heads, unable to fathom the idea of putting off work and life and independence for another four years, at the end of which there would be a massive debt and no guarantee of success. Besides, the closest university was nearly two hours away.

It was a powerful dream—maybe too powerful, because to someone raised the way I was, it seemed more like a fantasy. Particularly when I tallied up the cost of living without income for four years. Particularly when reality came crashing down on me, first semester. For monetary reasons, I had to live at home and quickly found the commute in my second-hand Gremlin to be almost unbearable. Later, I shared an apartment near campus with some friends, returning home each weekend with a sack of laundry. Worse, my classes were boring, keeping my grades decent was a struggle and dealing with a couple of bad professors nearly broke me.