Читать книгу Adrift: A True Story of Love, Loss and Survival at Sea - Susea McGearhart - Страница 6

One On the Firing Line

ОглавлениеHearing the clank of the anchor shank as it hit the bow roller, I turned my attention to Richard. With a grand gesture, he waved to me—“Let’s go!” I shifted the engine into forward. As I nudged the throttle, Hazana gathered speed and we headed out of Papeete Harbor on the island of Tahiti. It was September 22, 1983, at 1330. In a month we’d be back in San Diego, California. If only I were more excited. I hated to leave the South Pacific. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to see my family and friends, it was just too soon. We’d only been gone from California for six months and had originally planned to cruise the South Pacific islands and New Zealand before visiting home again. This change in plan left me feeling ambivalent. But as Richard pointed out, this yacht-delivery job was a dream come true—too good to pass up.

Shouts from the shore drew my attention. Turning around, I saw some of our friends waving good-bye. I stood up on the helm seat and waved with both arms high in the air as I steered with my bare left foot. I felt a pinch on my big toe as Richard took the helm with one arm and put the other around my waist. I looked down into his China blue eyes. They were full of joy. He squeezed me close and kissed my pareu-covered stomach. I couldn’t help but smile, he was like a young boy in his excitement.

“Anchors aweigh, love.”

“Yep, anchors aweigh!” I chimed back.

My eyes teared as I gave one final wave to the friends on the wharf who now appeared as lampposts on the quay. The familiar knot in my throat was a reminder of how hard it always is to leave, the thought that you may never meet again. Even though we will be back soon, I reminded myself, our friends will probably not be there. Sailors don’t stay long in one place—they travel on.

I took the wheel as Richard hoisted the mainsail. Taking a deep breath I scanned the horizon. The island of Moorea stood out to the northwest. Oh, how I loved the sea! I steered the boat into the wind, and the mainsail cracked and flogged as Richard launched the canvas up the sail track. With the boat turned downwind, the roller-furling jib escaped as slickly as a raindrop on glass. Hazana comfortably heeled over. What a yacht this Trintella is, I thought. Forty-four feet of precision. So plush compared to our Mayaluga.

Watching Richard trim Hazana’s sails, I reflected on how hard it had been for him to say good-bye to Mayaluga. He had built her in South Africa and he named her after the Swazi word meaning “one who goes over the horizon.” She had been his home for many years, and he had sailed the thirty-six-foot ferro-cement cutter halfway around the world. Mayaluga’s lines were sleek and pleasing to the eye, her interior a craftsman’s dream, with laminated mahogany deck beams, gleaming from layers of velvety varnish, and a sole—floor—made of teak and holly.

To avoid thinking too much about what we would be leaving behind, we had both kept busy during our last days aboard Mayaluga. I was preoccupied with packing all the clothes and personal things we would need in the two hemispheres we’d be sailing through and visiting in during the next four months: T-shirts for fall in San Diego. Jackets for Christmas in England. Sweatshirts for early winter back in San Diego. Pareus and shorts for our return in late January to Tahiti. Richard had focused on preparing Mayaluga for the months ahead without us.

She’d be safe in Mataiea Bay. Our friend Haipade, who lives at the bay with his wife, Antoinette, and their three children, promised to run her engine for us once a week. We took special care to prop up all the cushions and boards so the humid air of Tahiti could circulate. We left the big awning up to help protect her brightwork from the intense sun and cracked open a hatch under the awning.

When we left Mayaluga my back was turned to her as Richard rowed us to shore. I could not see his eyes through his sunglasses, but I knew they were misty. “I know Haipade will take good care of her,” I assured him.

“Yeah, he will. This bay is completely protected.”

“Besides, we’ll be back in no time. Right-o?”

“Right-o.” He smiled at me for having mimicked his British accent.

Now, aboard the Hazana, the wind shifted and I altered our course 10 degrees. Richard leaned down in front of me, blocking my view. “You okay?”

“Sure.”

Going behind me, he uncleated the halyard to raise the mizzen sail. “Isn’t this great?”

It was great. Great weather, great wind, and great company. His optimism was contagious. Isn’t this what sailing’s all about? I thought. Adventure. Going for it. Hell—time would fly.

* * *

The log entry for our first day out read: “Perfect day. Tetiaroa abeam. Full moon. Making 5 kts. in calm sea under all plain sail.”

Day Two, we were making six knots under the mainsail and double headsails. Later in the day we had to sheet all the sails in hard to combat the north-northeast wind.

Day Three, we were still pounding into the wind. Hazana held up well, but we felt fatigued. A thirty-five-knot squall hit later in the day. We rolled in the genny, dropped the mainsail, and sailed under staysail and mizzen.

The clap of a wave against Hazana’s port bow startled me. I ducked my head to block the spray. There was no way we’d be easing the sheets—spilling the wind from the sails to make the ride more comfortable—for we had committed to deliver Hazana, and it was San Diego or bust.

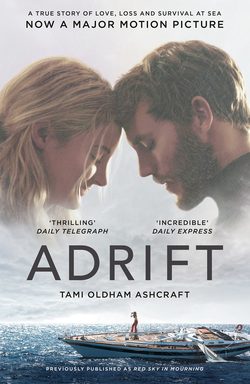

Richard and me aboard Mayaluga

Courtesy of the author

I watched the aqua and teal ocean colors commingle and dissolve into the deeper seas’ midnight blue. San Diego or bust, I mused. I always return to San Diego—home sweet home. It seemed so long ago that I had worked in the health food store and graduated from Pt. Loma High. I remembered how I grabbed that diploma and split—cut every cord keeping me grounded. All I wanted to do was cross the border into Mexico and surf its fantastic waves. Back then, it was Mexico or bust. I smiled, remembering how important it was for me to be free, on my own. I bought a 1969 VW bus, named her Buela, and talked my friend Michelle into taking off with me. We threw our surfboards on the roof rack and breezed through customs for Todos Santos with its promise of great waves to surf and adventures to be had. That was fall 1978.

Yacht Hazana, a Trintella 44'

Courtesy of Trintella Yachts, Holland

Michelle and I made camp on the beach at Todos Santos with other American surfers. For a month, all we did was surf, eat, party, and sleep. But, when Michelle couldn’t shake the obligations she had waiting for her back home any longer, she reluctantly left, hitching a ride north.

I made friends with a local family, the Jimenezes. I learned enough Spanish to get by and had fun teaching their five kids English. They lived and farmed on leased land. I’d help them pick tomatoes and cilantro, and in exchange, they’d allow me to keep the overripe tomatoes to make salsa to sell to the gringos on the beach. My little business was lucrative enough to subsist on, so I didn’t have to dip into my savings.

With so many Americans coming and going I never felt lonely and I never felt scared just being alone. Every week or so I would drive into Cabo San Lucas or La Paz for supplies. In Cabo there was a little sidewalk greasy spoon that served up a great Mexican breakfast. Lots of the gringos off cruising boats hung out there. The restaurant was a funky cinder-block building with a take-out window on the side. All of the seating was outside. There was a menu near the window and next to that was a huge bulletin board the size of a sheet of plywood. All kinds of messages and announcements were pinned onto this board.

One morning I saw an ad that caught my attention. “Crew wanted. Sailing experience not necessary. Cooking a must. Departing for French Polynesia at the end of the month.” I didn’t even know where French Polynesia was, but the sound of it lured me. “Contact Fred S/V Tangaroa.”

“Hey,” I yelled to Drew, a cruiser I’d met, “what does S-slash-V mean?”

“S-slash-V? It means sailing vessel, babe.”

“Thanks, babe.”

Ah, so the Tangaroa was a sailing vessel. Not having a VHF radio to hail Tangaroa, I walked to the beach and studied the many sailboats at anchor. As they swung with the current I could read their names, and soon I spotted Tangaroa. Its dinghy was tied to the stern, so I knew its owner was still on board. I kicked back on the warm sand and waited for someone to row ashore. After some time had passed, I saw an older man get into the dinghy and row in.

After he had secured the skiff on the beach, I approached him.

“Are you Fred?”

“Yes,” he said, quickly looking me over.

“I saw your want ad for crew and I’m interested.”

He invited me to have a cold cerveza up at the Muy Hambre cabana. Over the cerveza I told Fred the only boat I had ever sailed was my dad’s Hobie Cat in San Diego Bay, so I didn’t know a thing about sailing, let alone sailing across the ocean to a foreign port. Fred told me his boat was a custom-built Dreadnought 32. We discussed what my responsibilities would be on board, namely cooking and taking watches. I said that if what he really wanted was a “partner” I wasn’t interested. He told me he was recovering from a Tabasco-laden divorce and the last thing in the world he wanted or needed right then was a partner. All I would need to do was cook and stand watch.

With all the cards on the table, we agreed to go on a shakedown cruise—a trip to see how I took to sailing. We sailed to La Paz, 170 miles away.

It was a fabulous, two-day trip. Fred was the gentleman he promised to be and I took to sailing like a fish to water. I signed on the Tangaroa. My mom was more apprehensive about my sailing off into the wild blue yonder than my dad, but she knew she couldn’t stop me, just like she hadn’t been able to stop me from coming to Mexico nine months earlier.

When I returned to Todos Santos, the Jimenezes said it would be okay for me to leave my bus parked there. Years later I learned it had become a livestock feeder. They’d dump food into the sunroof and open the side doors so it could spill out, conveniently feeding the pigs.

Fred and I left Cabo in March 1979. The passage down to the Marquesas was a wonderful learning experience for me. I spent a lot of time at the wheel learning the feel of maneuvering a vessel through the dense sea. The only bummer was that Fred and I were like oil and water. He, in his mid-fifties, liked classical music. I, nineteen, liked rock ’n’ roll. He liked gourmet cuisine, I liked vegetarian meals. He was disciplined. I was carefree. He was an impressive man—posture perfect, body perfect, tan perfect. But all that was way too perfect for me.

One day, the horizon gave birth to volcanic peaks. I was breathless, seeing land after being surrounded for thirty-two days by nothing but blue seas and blue sky. Dense peaks split what had been a monotonous horizon line. It was a mystical sight that brought tears to my eyes. I wondered if this was how Christopher Columbus felt when he first saw land. Fred and I were barely speaking to each other by this time. I could hardly wait to get off Tangaroa, although I knew my desire to sail and explore had just begun.

Fred had told me we’d need to post an $850 bond upon checking into customs at Nuku Hiva, one of the Marquesan Islands of French Polynesia. But, being a novice traveler, I never dreamed my money, which was in pesos, was something the Marquesans wouldn’t recognize as a trading currency. Fred posted the bond for me, but it meant I had to keep crewing and cooking for him. I mailed all my pesos to my mom in San Diego, who said via telephone that she’d convert them to American dollars and mail the exchange back to me in care of General Delivery, Papeete, Tahiti.

During that time, I met Darla and Joey, who were also crewing on a yacht. We became fast friends. A small group of us crewmates, all about the same age, ended up fraternizing, and to keep us from committing mutiny, our captains decided to buddy-boat together through the Marquesan Island group.

Fred and I were the first boat in our group to leave the Marquesas and head for the Tuamotu Archipelago. It would be a three-day trip, and we deliberately timed it to arrive on a full moon, which would give us the most available light at night to navigate the atolls in case we arrived later than planned. Atolls are low-lying, ring-shaped coral reefs enclosing a lagoon. Because atolls are not easily seen and are surrounded by underwater coral reefs, they are dangerous to the mariner. Going aground on one can ravage the underside of a hull and sink a boat in minutes. The highest points on an atoll are the forty-foot palm trees swaying in the tradewinds. Due to the curvature of the earth and the fact that you are in a boat rolling with the sea, forty feet is not as obvious as a four-story building. Palm trees are the first indication to a mariner that solid ground is near.

It had been suggested that Fred and I look for certain ships and boats that had gone aground on these atolls, and to use the old hulks as points of navigation. Sailing past the wrecks on the reefs made me realize how important it is that everyone on board a boat be aware of the dangers and know how to navigate through hazardous areas. This was something I thought Fred knew.

Our first port of call was to be Manihi. Fred calculated it would be early morning before we spotted the atoll, giving us plenty of time and good light to find the lagoon entrance. When late morning came and we still hadn’t seen anything, I started to get worried. It wasn’t until one o’clock in the afternoon—when we saw the tips of palm trees blowing in the distance—that I could finally sigh in relief. Before long we were close enough to try to locate the entrance shown on the chart. We looked for a lull in the streams of white water, but all we saw was one long breaker. Fred explained that often waves break on either side of a lagoon’s channel, making it hard to distinguish the cut in the coral polyps.

Fred and I took turns looking through the binoculars, voraciously scanning the breakers along the shoreline. Finally I climbed up the mast steps to the spreaders—the crossbars on the mast—and wrapped my legs and one arm around the mast, surveying the tropical isle through the binoculars. The land appeared continuous, with no cut. We sailed completely around the atoll and still did not find an entrance. My nerves were taut and Fred refused to admit we were lost. The sun was quickly setting.

Through heated words we both conceded that we must have been set—that is, pushed—to the west, and that we had circumnavigated the atoll Ahe instead of Manihi. So we agreed to sail on through the night to Rangiroa.

Both of us were on edge that night. We stayed awake, watching and listening for any waves that might be breaking across a reef. It was that night, in my fear, that I realized I never wanted to be in such a position again. I needed to learn to navigate.

At first light we saw our destination. It was like the palms were waving a special hello to me. Around midmorning, we located the pass. This time it was easy to see where the white water petered out and then churned up again. The shift in color along the shoreline made the channel obvious. We could see a yacht flying an American flag tied to the village loading dock. We maneuvered into the dock, with help from the couple off the other boat. I jumped onto the dock and exhaustedly said to the woman: “Man, am I glad to be here in Rangiroa.”

“Rangiroa? You’re not in Rangiroa. You’re in Apataki!”

I was shocked. I leaped back on Tangaroa and went below to look at the chart. We had been set over a hundred miles southeast. What we had thought was the atoll of Ahe had actually been the atoll Takapoto, one of the atolls with no entrance.

I had now lost all confidence in Fred. I endured the five-day passage to Tahiti seething with anger toward him. My bags were packed two days before we arrived. I was eager to jump ship and leave the Tangaroa far behind me.

In Tahiti, I saw my friend Joey at an outside café; he told me he had signed on the schooner Sofia as a cook. I asked about Sofia. She wasn’t a luxury liner by any means, he said, having been built in 1921, but she was awesome: a 123-foot, three-masted topsail schooner that was cooperatively owned. He added that the accommodations were rugged: The head, for example, was a toilet seat mounted on a metal bowl located on the aft deck, rigged to dump overboard. The galley had four kerosene burners and one large diesel stove, and the sink pumped only saltwater. Fresh water was allowed for drinking and cooking only, not to be wasted on such frivolous things as rinsing saltwater off the dishes.

The membership fee to join the sailing cooperative was three thousand dollars. The cooks had to pay only fifteen hundred dollars. Joey set the hook when he told me the crew of Sofia was looking for someone to fill the other part-time cook’s position. The next day I went to the schooner, applied, and got the position, becoming a permanent crewmember.

Though primitive, Sofia did have character. She carried a crew of ten to sixteen people. Her ribs creaked of history and adventure. She was heading for New Zealand via all the South Pacific island groups. Those days on Sofia were some of the best imaginable. The freedom of being on crystal blue water while sailing a square-rigger in glorious sunshine was magic. The camaraderie of the crew was well balanced. I was able to learn my sailing and boson skills and the basics of navigation, as well as cooking and how to help organize and instruct people on the art of sailing. It was like being in one of Southern California’s greatest colleges: Sofia—U.S. “Sea.”

Once in New Zealand we headed for a little town called Nelson, located on the northern tip of the South Island in Cook Strait.

While our Sofia was set to stay in Nelson for more than a year for repair work, I was offered a fishing job on a boat named Pandora. She was owned and operated by a former Sofia crewmember who stopped by the ship looking for crew. I signed on for an albacore season and ended up fishing two albacore seasons and a grouper season. The money was good, and I loved the challenging life of fishing—the sea popping like popcorn, with fish on every line.

While I was fishing, Sofia received a movie offer and the producer wanted the ship in Auckland for the filming. I had left most of my things—photos, letters, and clothes—on board, as I planned to reunite with Sofia in Auckland when the albacore season was over.

Sofia never made it. She sank in a bad storm off the northernmost tip of the North Island of New Zealand—Cape Reinga. One woman drowned when the ship went down. The sixteen survivors were at sea in two life rafts for five days. They were finally rescued by a passing Russian freighter, which located them thanks to their last flare.

I was at sea fishing when notified of the sinking. The boat I was on took me back to shore, and I flew to meet the Sofia crew in Wellington. All my plans had just sunk, along with an innocent young woman and a beautiful ship, with the snap of a finger. I wasn’t sure what to do next. My visa, along with other Sofia crewmembers’, had expired. I had nothing left but the clothes I had taken fishing and a few odds and ends. Even then my roots reached back to San Diego—only way back then, I had been out of the country for three years, not a mere six months, like now.

Richard poked his head out from below and said, “ETA thirty days, love.”

I smiled broadly, for after having looked back on my inauspicious beginnings as a professional sailor, I was comforted by the faith I felt in Richard. Richard made it worthwhile being anywhere, even in the midst of this churning sea.

On the fifth day out of Tahiti, Hazana plowed the seas under genny and mizzen, making six knots. A deck fitting came loose and saltwater leaked onto the single-side band radio, shorting it out. The constant rolling from the northeast winds robbed us of our sleep. Our bodies were tense from deck gear clattering, the sails snapping and the rough ride.

The next day brought a reprieve. The wind came around to our beam and pushed us easterly, which is exactly what we needed. Richard wrote “Bliss” in the logbook. We decided to ease the sails and run off a little.

Basking in the sun, I twirled the lover’s knot ring Richard had made me. Looking across the cockpit, I let my eyes wander over his muscular body. I admired his topaz-colored hair, wavy like the sea, and his short-cropped, full beard, bleached gold from the sun.

Richard wrote in Hazana’s logbook the next day: “I have now given up any illusions that the SE trades will ever do better than E! Now under 2nd reefed main, staysail, rolled up genny (½) & mizzen—flying 6 kts.”

The Brooks & Gatehouse wind indicator gave out on Day Eight.

“I hope no more of this bloody equipment breaks down,” Richard exclaimed to me.

“Could it be corrosion, or . . . ?”

“Sod corrosion. It’s bloody high-tech electronics. The sun may not shine every day, but when it does, at least it will tell you exactly where you are.”

“Then sod bloody high-tech electronics!” I teased, slapping my palm on the seat locker.

For the next three days Hazana flew. The full sails reflected the salmon-colored sun, and we enjoyed reading and relaxing, and getting some much-needed sleep.

* * *

Sunday, October 2, Day Eleven on Hazana, was special for Richard and me. At dusk, phosphorescence sparkled in the turquoise sea. We opened a bottle of wine and toasted our crossing the equator that day and entering the northern hemisphere.

Ahead of us shot a geyser of silver and translucent green spray: A large pod of pilot whales was coming to play with Hazana. We connected the self-steering vane and went to the bow to watch them leap and sing their high-pitched greeting. Grasping the stainless steel pulpit, Richard leaned against my back, his bearded cheek next to mine as the whales created beautiful crisscrossing streamers of chartreuse in front of us.

“Aren’t the whales magical, love?” he asked, fascinated.

“Look how they surface and dive,” he said as he slowly started undulating against my backside. As Hazana rose over the next swell, he whispered in my ear, “Surface . . .” And as the bow plunged into the trough, he said, “Dive.”

“You could be a whale, Richard,” I teased.

“I am a whale, love. See, I’m surfacing”—he nudged me forward, the rhythm of the whales sparking something amorous in him—“and now I’m going to dive.”

As Hazana glided down into the trough, Richard reached around and untied my pareu as he clung onto me with his knees. He knotted the material onto the pulpit with a ring knot and cupped my breasts with his warm hands. I let go of the bow pulpit and stretched my arms out wide, Hazana’s fair figurehead.

“Ummm,” I hummed.

“I want to dive with you, Tami,” Richard murmured in my ear. “I want to surface and dive as these wild mammals do.” I reached back and undid his shorts. They fell onto the teak deck.

With growing momentum we surfaced and dived, surfaced and dived, wild and free like the whales, before God, and heaven, and sky. Hazana, the queen whale, set the rolling rhythm we matched.

I later wrote in the logbook: “Bliss!”

* * *

Day Twelve: We hoisted the multipurpose sail, the MPS, which is very lightweight, and made four knots with the southeast trades finally catching us. The trades stayed with us for a number of days, pushing us to the east. We often saw whales, and now dolphins were showing their cheerful faces.

* * *

Dawn of October 8 broke gray, rainy, and miserable. The winds were unpredictable. They gusted from southeast to southwest and back around from the north. We were up near the bow checking the rig when a small land bird crashed onto the foredeck. The poor thing panted, unsteady on its short toothpick legs. Richard got a towel and dropped it over the bird. Scooping it up, he brought the bird to the cockpit, out of the rain and wind. Behind the windscreen, on top of the roof of the cabin, it squatted low, ruffling its wet feathers to warm its tired body. I crumbled a piece of bread, but the bird appeared too afraid to eat. The absurd winds must have blown the tiny bird far offshore. Richard later scribbled, “Cyclonic?” in the logbook.

As I read the word “Cyclonic?” in his log entry, I wondered what that meant to him. Could it be that we were sailing through some rogue whirlwinds? Is that possible? Had the little bird gotten trapped in the clocking wind without the strength or wherewithal to break free? Did Richard fear our getting trapped too? I’d been in plenty of clocking winds in the past few years and never considered them cyclonic. Richard didn’t appear overly concerned, so I took it in stride too.

The next day the weather channel WWV informed us the storm they had been tracking off the coast of Central America was now being classified as Tropical Depression Sonia. They said it was centered at 13° N by 136° W and traveling west at seven knots. That put her over a hundred miles west of us.

WWV also warned of a different tropical storm brewing off the coast of Central America. They were referring to it as Raymond. In comparing our course, 11° N and 129° W heading north-northeast, to the course Raymond was traveling, 12° N and 107° W and heading west at twelve knots, Richard wrote, “Watch this one.”

“Watch this one?” Storms come and go, I thought, often petering out. I had learned that while fishing in New Zealand. Making note of it was Richard’s way of staying on top of things. Unfazed, I just kept up with the odds and ends of our daily routine like cooking, cleaning, steering, and reading. It was especially joyful to sit in the cockpit writing a letter or two to friends left in Tahiti that I would later post in San Diego.

Near midnight the wind dropped. Then it came around to the east-northeast, which fueled Raymond’s fury. We got hit with squalls and rain.

* * *

Monday, October 10, the wind veered to the north. At five in the morning, we changed our heading to north-northwest to gain speed. Our goal was to get as far north of Raymond’s track as possible.

The wind died down to one to two knots, and we ended up motoring for four hours. But by noon, when the wind started screaming, we shut down the engine and put two reefs in the main. It was the smallest we could make the sail without taking it down, and we needed all the speed we could get. We had the staysail up and the genny was reefed also. We were plowing away at five knots to the north-northwest. Tropical Storm Raymond was now at 12° N and 111° W, heading due west. The bird was gone; it had flown the coop.

We decided to fly more sail in an attempt to run north of the oncoming storm. Taut lines, also known as jack lines, ran along each side of the boat from the bow to the stern. This gave us something to clip our safety harness tethers onto while working on the deck. We pushed Hazana to her max. There was no choice—we had to get out of the path of the storm. This storm was quickly surpassing the two horrendous storms I had experienced in the Pacific before I met Richard. I knew Richard had had his ass kicked while crossing the Gulf of Tehuantepec in Mexico on his way to San Diego. But this storm was rapidly turning into the worst conditions we had ever experienced together.

Richard and I got busy clearing the decks, just in case the conditions continued to worsen; we didn’t need heavy objects flying around. We hauled the extra five-gallon jury-jugs of diesel down below and secured them in the head. They were heavy and it was difficult to move them in the rough seas.

At 0200 the next morning, the genny blew out. The ripped material thrashed violently in the wind; its staccato cracks and snaps were deafening. Turning on the engine and engaging the autopilot, Richard and I cautiously worked our way up to the mainmast, clipping our safety harness tethers onto the jack line as we went forward. “You slack the . . .”

“WHAT?” I yelled over the wailing wind.

“YOU SLACK THE HALYARD WHEN I GET UP THERE, AND I’LL PULL HER DOWN.”

“OKAY,” I shouted back, loosening the line.

Richard fought his way to the bow. I was terrified watching him slither forward. Gallons of cold water exploded over the bow on top of him, drenching me too. Hazana reared over the rising swells. The ruined sail whipped violently and dangerously in the wind.

Richard couldn’t get the sail down. Finally he came back to me.

“SHE WON’T BUDGE. CLEAT OFF THE END OF THE HALYARD, AND COME UP AND HELP ME PULL HER DOWN.”

I did as he said and slowly worked myself forward on all fours, ducking my head with each dousing of saltwater. We tugged and pulled on the sail as it volleyed madly in the wind. Finally, after my fingers were blistered from trying to grip the wet sailcloth, the sail came down with a thud, half burying us. We gathered it up quickly and sloppily lashed it down. We then slid the number-one jib into the foil, and I tied the sheet—the line—onto the sail’s clew. I made my way back to the cockpit making sure the line was not tangled—fouled—on anything.

Richard went to the mainmast, wrapped the halyard around the winch, and raised as much of the sail as he could by hand. I crawled up to the mainmast and pulled in the excess line while he cranked on the winch, raising the sail the rest of the way. It flogged furiously, like laundry left on a line in a sudden summer squall. We were afraid this sail would rip too. Once the sail was almost completely hoisted, I slithered as fast as I could back to the cockpit while Richard secured the halyard. I cranked like hell on the winch to bring the sail in. Richard came back to the cockpit and gave me a hand getting the sail trimmed. This sail change took us almost two hours. Richard and I were spent and wet, and we needed to eat. In between a set of swells, I slid open the hatch and quickly went down into the cabin before cold ocean spray could follow me in.

It was hot inside Hazana with all the hatches shut. She was moving like a raft in rapids. What would be simple to prepare, I questioned myself, instant chicken soup? As I set the pot of water on the propane stove to boil, I secured the pot clamps to hold it. I peeled off my dripping foul weather gear and sat down exhausted on the quarter berth.

* * *

Seven hours later, after the horrendous sail change, Raymond was still traveling west at latitude 12° N. Richard scribbled in the logbook: “We’re OK.” Obviously our northerly heading was taking us away from Raymond’s westerly path, so we seemed to be getting out of harm’s way.

All through the rest of the day, the wind and the size of the swells steadily increased. White water blew off the crests of the waves, creating a constant shower of saltwater spray. The ocean appeared powdered, as if white feathers had burst out of a down pillow. Tropical Storm Raymond was now being classified as Hurricane Raymond. That meant the wind was a minimum of 75 miles an hour.

At 0930 October 11, the present forecast put Hurricane Raymond at 12° N and spinning along a west-northwest course. Richard screamed at the radio, “WHY THE BLOODY HELL ARE YOU TACKING TO THE NORTH? STAY THE HELL AWAY FROM US!” He had let down his stiff upper lip, and more than anger exploded—it was fear, raw bloody fear. My ribs constricted—an instinct to protect my heart and soul. Richard hurriedly recorded: “We’re on the firing line.” We flew every sail to its maximum capacity. I silently lamented over the useless torn genny; it was a sail we could have really used now because it was larger than the number-one jib. Richard told me to alter course to the southwest. If we couldn’t situate ourselves above Raymond, maybe within the next twenty-four hours we could sneak to the south of the center and reach the navigable semicircle—the safer quadrant that would push us out of the spinning vortex instead of sucking us in. There weren’t many options; we had to do something. It would be pointless to start the engine, for by now we were sailing way beyond hull speed as it was. Richard’s nervousness and fear were obvious. I had never seen him like this. He mumbled a lot to himself, and when I asked what he said, he’d shake his head and say, “Nothing love, nothing.”

But how could I ignore the way he scanned the sea to our east and repeatedly adjusted the sails, desperate to gain even a smidgen of a knot away from the forging Raymond? Adrenaline surged through me—fight or flight. There was no way to fly out of this mess, so it was fight. Fight, fight, fight.

At three o’clock that afternoon the updated weather report told us Raymond had altered its direction from west-northwest to due west with gusts to 140 knots. The afternoon sun sight gave us a second line of position. This indicated we would collide with Raymond if we continued on our southwest heading. We immediately came about and headed northeast again, trying to get as far away from Raymond as possible. The conditions were already rough enough. But to get clobbered by a hurricane would mean that we could lose the rig and really be disabled out here in the middle of nowhere. We did not fear for our lives, as we knew Trintellas were built to withstand the strongest of sea conditions, but the fact that one of us could get seriously hurt loomed unexpressed in both of our minds. With a shaky hand Richard inscribed, “All we can do is pray.”

Later that night, the spinnaker pole’s top fitting broke loose from the mainmast and the pole came crashing down, trailing sideways in the water. Richard and I scrambled to the mainmast trying to save the spinnaker pole. He grabbed it before the force of the water could break the bottom fitting and suck the pole overboard. It took both of us to lash all of its fifteen feet down on the deck. Creeping back to the cockpit we saw that a portion of the mizzen sail had escaped from its slides and was now whipping frantically in the wind.

“JESUS CHRIST, WHAT’S NEXT?” Richard roared. He stepped out of the cockpit, clipped his safety harness onto the mizzenmast, and released the mizzen halyard. Once the mizzen was down, he lashed it onto the mizzen boom.

As he came back to me at the wheel, I noticed how dark the shadows were under his eyes. He tried not to sound sarcastic as he said, “Not much else can go wrong.”

“We’ll be okay. We’ll be okay, love,” I said, trying to convince both of us.

In the darkness, the ocean was highlighted with thick white caps of foam—a boiling cauldron. The barometer had dropped way down the scale as the wind’s wail steadily increased, the seas becoming even steeper, angrier, more aggressive. We were terrified Raymond was catching us, but there wasn’t a damn thing we could do about it but sail and motor as fast and as hard as possible.

We stayed on watch, taking turns going below to get whatever rest we could. Our muscles ached from fighting the wheel while trying to negotiate the pounding, erratic seas. Night had never lasted so long.

The next morning broke cinder gray with spotty sunlight shedding an overcast hue on brothy seas. Ocean spray slapped us constantly in the face. Wind was a steady forty knots. We reefed all sails and galloped with a handkerchief of a jib and mainsail. At least it helped steady the boat.

About 1000 the seas arched into skyscrapers, looming over our boat. The anemometer—the wind speed gauge—now read a steady sixty knots and we were forced to take down all sails and maintain our position under bare poles with the engine running. By noon the wind was a sustained one hundred knots. The churning spray was ceaseless. Richard came topside and handed me the EPIRB (emergency position-indicating radio device), as he took the wheel. “HERE, I WANT YOU TO PUT THIS ON.”

“WHAT ABOUT YOU?”

“TAMI, IF WE HAD TWO I’D PUT ONE ON. JUST MAKE ME FEEL BETTER, AND PUT THE BLOODY THING ON.”

So, I did. I fastened my safety harness tether to the binnacle and steered while Richard went below to try to figure out our location now and get an updated position of the hurricane. All he could hear between the pounding and screech of the wind was static. There was no way he could risk bringing the radio outside with the sea constantly cascading over the boat.

Richard came topside, fastened his safety harness, and took the wheel. I sat huddled against the cockpit coaming, holding on with all my strength to the cleat where my tether was fastened. We were helpless while staring at the raging scene around us. The sound of the screaming wind was unnerving. The hull raised to dizzying heights and dove into chasms. Could the seas swallow us? The ascent of the boat over the monstrous waves sent the hull airborne into a free fall that smashed down with a shudder. I was horrified Hazana would split wide open. Finally I shouted to Richard, “IS THIS IT? CAN IT GET ANY WORSE?”

“NO. HANG ON, LOVE; BE MY BRAVE GIRL. SOMEDAY WE’LL TELL OUR GRANDCHILDREN HOW WE SURVIVED HURRICANE RAYMOND.”

“IF WE SURVIVE,” I hollered back.

“WE WILL. GO BELOW AND TRY TO REST.”

“WHAT HAPPENS IF WE ROLL OVER? I DON’T WANT TO LEAVE YOU ALONE.”

“THE BOAT WOULD RIGHT ITSELF. LOOK, I’M SECURE,” he said, giving a sharp tug on his tether. “I’D COME RIGHT BACK UP WITH IT.”

I looked at his tether secured to the cleat on the cockpit coaming.

“GO BELOW,” he urged. “KEEP YOUR EYE ON THE BAROMETER. LET ME KNOW THE MINUTE IT STARTS RISING.”

Reluctantly I got up, leaned out, and squeezed the back of Richard’s hand. The wind sounded like jet engines being thrown in reverse. I looked at the anemometer and gasped when I read 140 knots. With my mouth agape, I looked at Richard and followed his eyes up the mainmast in time to see the anemometer’s transducer fly into outer space.

“HOLD ON,” he yelled and cranked the wheel. I tumbled sideways as the hull was knocked down. I fell against the cockpit coaming. An avalanche of white water hit us. The boat ominously shuddered from bow to stern.

Richard anxiously glanced at me, water dripping down his face, fear jumping out of his intense blue eyes. Behind him rose sheer cliffs of white water, the tops blown into cyclones of spray by the ferocious wind. My eyes questioned his—I couldn’t hide my terror. He faltered, and then winked at me, thrusting his chin up, a signal for me to go below. His forced grin and lingering eye contact disappeared as I slammed the hatch shut.

I clung to the grab rail of the companionway ladder as I made my way down to the cabin below. The frenzied cadence of Hazana’s motion prevented me from doing anything but collapsing into the sea hammock rigged to the table, and I automatically secured the tether of my safety harness around the table’s post. I looked up at the ship’s clock: It was 1300 hours. My eyes dropped to the barometer: It was terrifyingly low—below the twenty-eight-inch mark. Dread engulfed me. I hugged the musty blanket to my chest as I was flung side to side in the hammock. No sooner had I closed my eyes when all motion stopped. Something felt very wrong, it became too quiet—this trough too deep.

“OHMIGOD!” I heard Richard scream.

My eyes popped open.

WHOMP!

I covered my head as I sailed into oblivion.