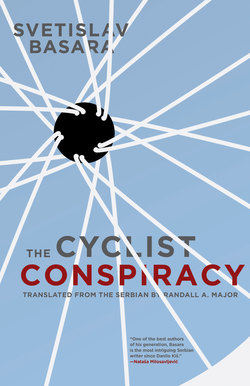

Читать книгу The Cyclist Conspiracy - Svetislav Basara - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

BY THE UnKNOWN COPYIST

At the end of 1898, crushed by inexplicable depression and fatigue, I left London, a lovely social position, a reputable name (that I will not mention here) and withdrew to the land of my ancestors in Western England, hoping that, far from the hustle and bustle of the city, I would find peace and dignity, and prepare for death. At the beginning, it seemed that nothing would come of my plan because, not far from my home, one of the nouveau riche had moved in, some sort of London private-eye, a detective who had been on the front pages of the scandalous chronicles for years; a chronic user of morphine and amateur violinist, who broke down at the very appearance of a velocipede because he had recently suffered a nervous breakdown. I do not know what related the velocipedes to his illness but, since that vehicle had attained a certain popularity amongst the young, his attacks occurred almost daily. I doubt that, in my life, I have met a man, and I have met plenty, who was more completely in love with himself. In truth, to be in love with anyone is a matter of the naïveté common to early youth, but to be in love with oneself, and therefore with the person we know best, means either to be an idiot or an evil man, and my neighbor was, I am convinced, both.

To make matters worse, this good-for-nothing, about whom people of dubious reputation had even written several trivial books for entertaining the masses, was constantly attempting to visit me, to give me gifts, to invite me to games of bridge and, worst of all, I tolerated these intrusions with a hypocrisy and patience that was amazing, if one considers my pitiful spiritual state. And yet, I am most thankful to him, that genius of shabby logic. And this is why: in order to defend myself from his onslaughts I began, using the excuse of my doctor’s advice, to take long walks to the shore of the ocean where I found a certain measure of peace in the silence, barely disturbed by the murmuring of waves and the whistle of the wind; by the way, I also learned, during a storm accompanied by roaring thunder, that the worst sort of noise is… the prattle of human voices in a closed room. If these words make me out to be a misanthropist to future readers, I will be satisfied. Was I not (like everyone else) a misanthropist who pretended to be a philanthropist in the tortuous farce of social life? Those walks helped me become aware that I had wasted my life in the constant presentation of myself as someone else, someone different than who I really am; that I put on the mask of a specter my whole life until finally, just as it says in the Caballah, I actually became a specter. I gave thanks to the Lord for mercifully doling out to me, near the end of my life, the flames of the worst suffering of the soul, for wracking my body with pain and insomnia; I was thankful for every suffering that opened my eyes, blinded before that by the trivial sparkle of worldly things.

During one such excursion, while the coachman waited for me in a nearby tavern, as I walked along the seastrand, I saw a shining object cast upon the beach by the high tide. I can be grateful to Providence and someone else that I descended the steep cliff, for I might well have broken my back or a leg. Far from it, that I feared for my life or my health; I was lethargic and fainthearted, and I would undertake such an effort for nothing – by earthly criteria – valuable. But the object sparkled mysteriously; that which greed could not do was done by curiosity, and I descended, wading knee-deep into the water, and I snatched it up. At first glance, it was just a common bottle of fine glass, carefully sealed with pitch. Immediately I called my driver and rode home. That evening, in the privacy of my study, I broke the bottle. Inside was a scroll of paper, the manuscript of Captain Adam Queensdale, dated 23 October 1761.

Although it had been well-protected, over the one hundred and twenty-five years the bottle had been carried by the ocean currents, the paper had suffered a degree of damage. I spent several exciting evenings copying the contents of the original which threatened to disintegrate into dust and ashes at any moment. The text contained a description of a shipwreck that only Captain Queensdale had survived; a description of the island, Ultima Thulae, north of Iceland, where the castaway was taken in by the inhabitants, members of the heretical sect of Two-Wheelers, exiled from Europe in the 14th century; a description of the life and rituals of the inhabitants, of their mythology and eschatology; and at the end, a copy of the holy text, The Purgatory of Sleep, the greater part of which, unfortunately, was so heavily damaged as to be unreadable.

Studying this tale, which had a healing effect on my soul, I decided to save it from oblivion, but also from the curiosity of the masses, from the quasi-scholars and sensationalists. The only way to do that was to act just as the bottle had acted toward me: I had to let the story find its readers by itself. Toward that end, I made six completely identical copies and inserted them into six expensive, but uninteresting, books. I sent the books to the addresses of reputable secondhand bookstores in London, Istanbul, Heidelberg, Reykjavik, Cairo and Bombay. They will, I am certain of it, know how to reach their readers. Everyone who comes to believe in their contents will do the same thing I did: he will make six copies of the text and find a way to release them into the world.

J. H. W.

4 July 1982