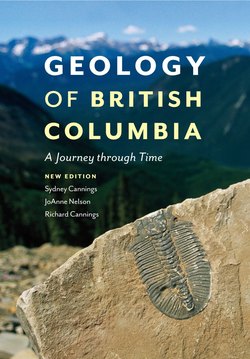

Читать книгу Geology of British Columbia - Sydney Cannings - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

AS BOYS WE poked into a lot of natural history—we looked at birds, we caught trout in small creeks, we helped our older brother make a butterfly collection, and—for a short time at least—we kept a leaf collection. But we poked a bit into geology, too. As small boys we looked wide-eyed at the perfect twigs of a dawn redwood from the White Lake fossil beds, marvelling when we were told they were millions of years old. And the cliffs nearby were made of lava, meaning that there were volcanoes here once, too. Our father had read Hugh Nasmith’s late glacial history of the Okanagan, so we learned that the Big Hollow of our toboggan runs was a glacial kettle, that the silt cliffs we clambered over were bottom sediments of Glacial Lake Penticton and that an ice dam at McIntyre Bluff south of Vaseux Lake had dammed the Okanagan drainage, sending the water north instead of south. One of our favourite spots was Coyote Rock, a giant boulder perched atop a tower of unconsolidated rock and silt. How did it get there? Geology is history, and every landscape is full of fascinating geological stories.

The Okanagan has a complex geological history, and in that respect it is a characteristic corner of British Columbia. The original gentle shores of this province have been squeezed, melted, broken, piled and sheared by collisions with offshore terranes, or pieces of the earth’s crust. The foreign rocks of the terranes added to the confusion of local rocks, and then glaciers came and piled immense quantities of rubble on top of the whole tableau.

But while all this was going on, animals and plants lived here—on land, in fresh water and in the Pacific. What did it look like back then? And how did the flora and fauna of British Columbia move, adapt and evolve with the changing landscape?

Our landscape is still changing. Vancouver Island is being squeezed narrower and higher as you read this. Many earthquakes shake the land and sea each year. The climate is warming and glaciers are receding further, for the moment. And trees, flowers, birds, bugs, bears and fish continue to move across the landscape, testing and altering ecosystems as they go. These are the stories told in the following pages. The link among them all is change, for they are stories of transformation.

The deciduous dawn redwood was a dominant tree of swampy areas in the B.C. Interior 45 million years ago. These fossil twiglets are from beds in the White Lake area near Penticton.