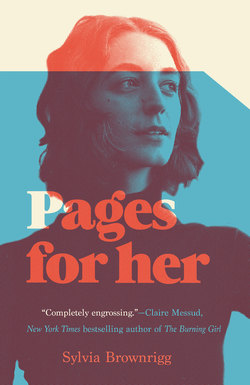

Читать книгу Pages For Her - Sylvia Brownrigg - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеDear Ms. Jansen

– the email began in its bland, black on gray tones.

It was the kind of missive you should read walking slowly up from the mailbox to your home (if your home weren’t so fraught), shaking the letter free from its envelope, which drifted down to the stone steps without your even noticing. The city’s distinctive mist would lend its drama to the occasion as you inhaled sharply, aware that your life was about to take an important turn.

Instead, here was Flannery at the bustling brown coffee shop with the punning name (Bean There, Done That, though it could as easily have been Common Grounds, or Café Olé), where entitled customers broadcast their coffee requests with precise specifications, and selected the worthiest scone from a windowed display of candidates. Seated at a counter, a suited professional spoke angrily into her cell phone, castigating someone about the delay in her insurance reimbursements; at a table near Flannery a young white man sat, styled in the studied casual of tech workers, his hands folded in the supplicant position, as he awaited an older Indian man for what looked like a job interview.

I’m writing from the Alumni Association. Recently we’ve been organizing more events on campus focused on women graduates, to inspire current students. I apologize for the late notice here but we have been putting together a three-day conference in October (19–21) called ‘Women Write the World’ and we are hoping you might be able to join us. Professor Margaret Carter of the English Department will be chairing the conference. We’ve got a great line-up of participants already, including . . .

A woman in her twenties who had recently had a hot flush of success with a sexually adventurous novel set in Thailand. (Li Mayer.) The well-heeled Bostonian who produced exquisite sentences and had won honors and plaudits. (Bishop. Flannery had worked hard not to envy her.) A television comedy writer (Chatterjee); the nation’s Poet Laureate (Jefferson); one brainy journalist who had produced the definitive work on Stalin’s gulags, and another who wrote a weekly political column for the New York Times. (Kessler, Green.) Yes, yes, yes. Flannery knew this roster, the gist if not every particular. It had been that kind of university. The great and the good attended it – winners of races, climbers of ladders, tappers up against the glass ceiling. Yes, those too. Women undergraduates had been permitted through Yale’s gates since 1969, though still struggled to have the faculty representation and fat slices of power that the institution’s men had. Hence, of course, this conference. Here we are: us girls! See how we’ve done!

Such politics were not central to Flannery these days. As an agitating twenty-something she had carried placards along the National Mall, protesting about women’s rights and freedom of choice, but lately the collective she poured her time into was made up of just three – and was mixed, in age and gender. From where she sat now, in Bean There, Done That, Flannery saw her younger activist self through a backward telescope, tiny and out of scale. The idea of appearing professionally, in a guise other than as the driver attached to her daughter or a softening embellishment to her husband, appealed to Flannery, and she was flattered to be asked, but her first reaction on reading the dates and location focused on logistics: how could she get there? Who would look after Willa? And what kind of resistance should Flannery expect from Charles to the prospect of her flying across the country for a gathering called Women Write the World? (‘Do they?’ she could imagine her husband challenging, with mock solemnity. ‘It’s a big world. That’s a lot to write.’)

Such were the dreary cogs that started turning in her mind, before another item stopped all the machinery cold. Then warm.

At the last name she saw on the list.

Moderating the proceedings . . .

There followed a name so vibrant to Flannery that it appeared to pulse in some foreign color on her screen, pomegranate red or a sleek jade green, not the black on gray of the others.

Professor Anne Arden.

A woman she once knew.