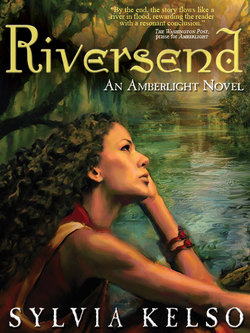

Читать книгу Riversend: An Amberlight Novel - Sylvia Kelso - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER I

The Diaspora. Week 1.

Tellurith’s Diary

However it feels, this is not a dream. I will not wake to my life’s remembered walls; to that Uphill view through wide glass windows, the House around me. The City beyond. I am already wide awake. Perched by a makeshift fire amid miles of dry rice paddies, in the heart of the Sahandan, with half a pilfered archive scroll and somebody’s old silverpoint; planning to make a record. Of where we are going. What we have begun.

But it is hard to begin this journal without turning it into a requiem. For how shall I go on without remembering all those who are gone? All my peers, my fellow House-heads: Damas and Eutharie and Ciruil, my rivals; Maeran and Denara and Sevitha, my enemies; Zhee and Ti’e and Averion, my allies; my friends. Averion above all, my lovely general.

And the women who followed them, the House and Craft-folk, the cutters and shapers and troublecrew; so many bringing their men as well. The Downhill clans, the workers and guilds and merchant folk. Even the guerilla raff who came for us or against us out of River Quarter. All the folk of Amberlight. All left, lost, gone.

But how shall I mourn the greatest loss of all? My dear, my darling, the surety under my heart, the life rising to my fingertips, the light in wall and statuette and mother-face, the voice to my silence, the measure to my song? The heart’s blood, the treasure, the bane of Amberlight. The city-killer, the king-maker. Pearl-rock. The qherrique.

Blown out of existence, with the armies that besieged us. Never to know, to feel, to share that unhuman answer’s mystery, ever again.

Yet who am I to complain? When I surrendered, at that mystery’s behest? When my—our—House survived, and relatively intact, after other Heads died with theirs? When most of my folk are here, to shape that House back round me? Safe out of Amberlight, bound for the Iskan marble quarry. Telluir House’s traditional holding; a fresh life, a new world. Above all, when I, unlike so many on either side, have brought both my men live out of the wreck?

Both of them. Ah. There begins the difference. We—I was used to sharing, yes, in old Amberlight. By House custom, four, five women take—took—a single husband, who dwelt modestly in the men’s tower, while we managed House and Crafts. Sharing a man, I am used to.

But not to two men sharing me.

If they will share. I am House-head still. I can command it. Will that make it happen? Two men together, not in the tower now, no rules laid down for them. Two such men as these?

Sarth, so much the pattern of Uphill Amberlight. I see him still, in those bronze silk trousers, gold-dusted muscles shaped in the tower gymnasium, bronze hair in waist-length lovelocks, gold-shaded eyelids, bronze-gold eyes in that perfect face. Tall, splendid, polished as his tower skills of music and conversation and love.

And the words, the delicate, drawling poison, that he could plant, surer than a Navy gunner, in my heart.

Jealousy, oh, yes. There is an abundance in Sarth of both bile and balm. Sweet work-Mother, how he could make me cringe in those days, after the boys—after I lost my children. After we lost our children; for a man in Uphill Amberlight, children are the only pride. And the worst disaster: a first-born son.

Bitter, deforming, hideous decorum: that only after a House woman’s first girl might her male children live. That cost me my first, and second, and third-born child; and with them my husband’s love.

Small wonder he compounded that poison on Alkhes. To Sarth, no doubt, in his very person as much insult as antithesis. Small and black-avised and wearing what comes handy. No polish, except in warfare. Outlander. Worse than outland; rankless, nameless, certainly spy, probably mercenary, possibly renegade. Taken in, street flotsam, to our infirmary, our men’s tower; named, by the qherrique itself, for the Dark, the holy quarter of the moon. Prisoner, sparring-partner, lover. House-head’s favorite, suave in silk and rubies. Troublecrew, lithe and lethal in killer’s black. In my bed, in my love; twined into my House.

Or was that Assandar? Before he lost his memory along with his money to that River Quarter gang? Coalition general, top-flight mercenary; imperial officer, caravan guardsman, with ties only to soldiery. Deadly in brawl or battle. Deadliest in his wits.

Resurrected with those memories, and locked in battle against me, the House, Amberlight. Is there any dividing them, troublecrew and mercenary, beloved and enemy, Alkhes and Assandar? Less one man than two at once.

And how will Sarth understand that?

Any more than he will understand Sarth?

But for the future, all our futures, that I glimpse—that I am trying to see—the men, these men, are the keystone. They have to understand. What do we have, if they cannot?

* * *

As I write this, it is quiet; camp pitched at last, after more hours of chaos with folk who never had to find a new home every night. Fireglow on the patched dun Dhasdeini tent wall behind me, on shadow and motion I know better than the rhythms of my heart: Hanni with the handful of slates and tallies she already calls Head’s records. Shia yet again stirring pots. Shapes that come and go, prowling our perimeter, Zuri, Azo, Verrith. Troublecrew at work. A snatch of acid voice out in the dust-light. Iatha, stewarding my House.

And the shadows that move inside my tent.

What are they doing? What do they say to each other? Twin shadows, one tall, one small; one with a stately elegance, one with a weapon’s tempered grace. If not now, with a slung arm and three ribs in a cincture of bandages, with bruises, grazes, contusions everywhere, from the huge black eye to the blisters in a stranger’s boots.

I tallied that damage this afternoon. All of it. When he caught us up. Obsessed lunatic, escaping, chased clear of the—catastrophe. Whatever the price. Salving, then abandoning his army, his conquest. Leaving a letter of resignation to the Emperor, before he cast himself, knowingly this time, on his enemies’ mercy. Riding, doubly outcast, incurably stubborn, after us.

And there was water in the last, bigger stream our ramshackle caravan labored over; an upstream pool, relatively clear of stagnance, sheltered by plumes of gold-tinged poplar and clumpy silver-gray hellien. A place to water a horse, and tie it up. And then, behind the shield of Zuri and her troublecrew, strip down my restored man; to purge away travel, battle, an old life.

I put the borrowed soap and towels on a tussock. He had halted, his back to me; trying to decide, forespent and one-handed, what to tackle first. But when I walked up and put both arms around him, he sighed, and leant back into my embrace.

His good hand covered mine. I locked the other over it. How to speak, in the body’s language, of joy beyond what had been mortal loss? I am too tall to burrow in his shoulder; he turned his face, burying it in my neck.

“Oh, Tel . . .”

Loss, and killing grief, and thankfulness, for what we had never thought to have again.

A long time after, he whispered, “I missed you so much . . .”

I started to undo the acrid, mud-smeared laborer’s shirt. Miss him, yes. What words can shape the truth of “miss”? The ache, the physical ache of it, like a cancer, night after night?

“All down the River—in Dhasdein—in the siege—all I could think was—I have to get back . . .”

He was fumbling, one-handed, with what had been an infantryman’s belt.

“Not just you—or this. I never understood what it meant, Tel. The—the House. I never had it before. Not belonging. Not like that.”

House-folk. Community, fellowship. Precious beyond all empathies. Except one.

The sword-ties had trapped his hand. I freed it. Pulled the heavy buckle loose. Undid the trouser strings beneath, found the hard, sunken belly muscles below that, and he caught his breath and pushed backward, twisting to find my mouth.

“Oh, gods, Tel—”

He was dirty and bristly as a porcupine, I could not even hold him tight. And when I let go he swayed, pressing a hand into his side.

“We better stop.” It was breathless as the shaky laugh. “Sorry—no good for any more. Not right now . . .”

I worked the shirt off, to bare the wad of soiled linen, wide as a packhorse’s surcingle, that girdled his ribs. He slid down on another tussock and scrabbled at the ties of the heavy, cross-laced cavalry boots. But when I knelt and set his hand aside he battled it, catching his breath. “No, don’t—Tellurith!”

The knots were solid. Drawing the boot-knife unearthed from some Verrainer’s tent-kit, I felt his hand brush my hair.

Breast-long, crinkle-curled, brandy-brown hair of Amberlight. He had undone it, releasing its mazes, that first night.

“I thought—you’d send me back . . .”

It was less than a whisper. I looked up. Our eyes locked. I could have stayed forever, his hand on my shoulder, my arm across his thigh, he bending over me, gathered between his knees.

“You should have known better than that.”

He lifted the hand to cup my cheek. I touched the splint’s edge, luckily not unseated by zealous handling, and murmured, “I’m sorry. Back on the road . . . Zuri was—upset.”

“I expected it.”

“Eh?”

“I thought they might kill me. Before I got to you.”

“Kill you! Sweet Mother—”

“They had the right.”

I let go the boot, half-off. He stared past me, mouth set, that silky black wing of hair, matted now, falling in his eyes.

“I was troublecrew.” He said it harshly. “One of them. I betrayed the trust.”

“And you’d have let them finish you. For that?”

“I betrayed the House.”

I worked one boot off. Started on the other. We both knew there was no reply to that.

“I had to go, Tel. Nothing could have stopped it. They’d made up their minds. All I could do was go back and try to get some say in it. Try to hold off the worst . . . Gods, do you have any idea what it took to get that command?”

I had to go back, he had said to me, at that first parley, after his troops sealed Amberlight. I had contracts, I had obligations. I couldn’t break them, and keep myself.

It made far more sense this time. Far harder, less noble, more likely sense, that our destruction was already destined, that Dhasdein and Verrain and Cataract had fixed on it, that he had indeed fought tooth and nail for the general’s command. Not to have his revenge on us. Simply, as he had tried, over and over, to protect his new loyalties. To save as much as he could of Amberlight.

I pulled the second boot off. Stood up and held out my hands. When he reached his feet again, I touched his cheek and said, “I can guess.”

Some of the strain went out of him, a long, soundless breath. Carefully, I worked the trousers down his hips. We were close beside the water. I gave him a hand down the stones.

It was evening, autumn, and a stream off the Iskans. He was out in two shaken gasps and I picked my way over him with the soap. When I took up the bucket he said, “I can get in again.”

“We’re upstream.”

“Yes, of course—”

He stopped.

In some ways that was the worst moment of all. Worse than losing him that first time, thinking myself betrayed. For this was the new life. I had taken him into it. And now I saw the gulf between us: that he, even he, who had begun as a foot soldier, who could feel a child-bereft woman’s grief, could so simply think—could just assume—it did not matter if we fouled the water.

With a camp of three hundred people downstream.

What woman of Amberlight could forget? Could act, were she the veriest stevedore, as if they were not part of her? Sweet work-Mother! I nearly shouted. You accused us of injustice! And you want to be part of us. Coming from a world like that: where even generals like you can’t see the people underneath.

“Tel. Tel. I’m sorry. I didn’t think. I’m not used—Tel, give me time. I’ll work at it. It won’t happen again.”

And he would work at it, fast as he had understood, it needed no pledge beyond those inimitable wits.

He was huddled over, clutching the bad arm, shivering as hard as his chattering teeth. I yanked the bucket over and sank it with one vehement swirl, heaved up and ran it to his side. “Hold on. I’ll be quick.”

When I had him dry, a pair of someone’s leggings, a Dhasdein infantry tunic and some cameleer’s coat on him, the shivering had almost stopped. He picked up the dirty clothes himself. It was true, he would work at it. Azo took the horse. Walking back into camp, I touched his cheek again. “I don’t have a razor, myself.”

“There’s one somewhere.” Meaning his own makeshift kit, slung in a knapsack at the saddlebow. “Only I can’t manage it . . .”

But someone else could. I pushed his hair back, clean now, if not so finely scented as once. “Will you let Azo take you wherever they’ve put me? I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

I had been Head when he first knew me. When did he not have to compete for my time? He moved the right arm to put it round me; winced. Tried to smile. “I won’t be going anywhere.”

* * *

After four nights on the road I could hope my target would be at his self-appointed work; hence out of my camp, and handily open to approach. I caught him just walking from the pair of Dhasdein five-man infantry shelters that had become Ahio the shaper’s tents.

“Sarth?”

He broke stride; swung round, mallet dangling. He smelt of cow dung and sweat instead of hyacinths, there was grease on his green and brown troublecrew shirt, his beautiful hair was tied back in a tail under yet another rascally straw hat. His features looked naked, without the men’s house-veil, his exquisite skin was sunburnt. But he could still make my pulse jump with that smile.

“What brings me this honor, Tellurith?”

Once it would have slid malice like a stiletto, straight between your ribs. How can I say what it was, to hear honest amusement instead?

“I need you for something, of course.” I smiled too, putting my hand on his arm. No hardship in either move. He was still so splendidly tall. And to him, fresh from the tower, there could be no greater compliment.

“A double honor. Might one ask . . . ?”

It had all come so happily, it was so logical, so apt. But now, of a sudden, there was a constriction in my breath.

“I just wanted you to—ah—”

He was waiting, brows up, that lovely new, open smile.

“Ah—”

Trust, warmth, love renewed. And I was going to smash it. With my own two hands.

“What is it, Tellurith?”

The voice had changed. In his own way he was as redoubtably shrewd as Alkhes. Just trained in a different field.

I looked up the five inches to those topaz eyes. So warm, so kind, so wholly concerned with me; the way he had used to ask, when nothing mattered more than solacing my woes.

“It’s Alkhes.”

I said it baldly. There was no other way.

“I see.”

“No, you don’t, Sarth, wait!” He had not moved. It was in himself he was going away from me, the warmth running like blood. “He didn’t get killed, he came after us, he—”

“He’s in your tent.”

“Sarth . . .”

How much explanation, how much plea, can you put in a single word?

“I’ll get my things out, now.”

“No! Listen to me! That’s not what I want!”

He stood there. Stone to the very eyes.

“You’re my husband—”

“Just temporary.”

The stiletto never cut so deep. I actually put a hand to my side. His muscles flexed to turn.

“Blast it, wait! It’s not temporary! That’s what I’m saying!”

It stopped him dead. All he could do was stare.

“He’s your lover—”

“I told you—!”

“Your favorite.”

I actually shook him. “Sarth, will you listen? This is not the tower and it’s not Amberlight. We can do what we want now. I can do what I want. You’re my husband and I’ve got you back. And I’m keeping you. I’m marrying him as well!”

For a while I thought he really had died. But eventually his face shifted. He started breathing again.

Looked down, and then, one by one, loosened my fingers from his arm.

“Tellurith.” He actually sounded groggy. “Even for you, this is—”

“For me it’s just good sense.” I had not meant to break it this way, but there was no going back.

“But you can’t—”

“We’re on our own now, and I can!”

He shook his head. “I don’t—”

“Do you want to go?”

People and beasts squirmed by us in the alleyway, children skirmished round our legs. The sky had gone ice-pink and lavender between the silhouettes of tent. I knew there were people, a whole camp’s routine waiting on me. But for that moment, we were alone.

And at last, so slowly, he shook his head.

I felt my breath go out. “I know it won’t be easy. I know I’m asking far too much. But if you could try . . .”

He was still looking at me. Those topaz eyes had darkened with the twilight, but he could not seem to blink. Then, once more, he shook his head.

My heart stopped. But he let the mallet drop. Groped for my hands. Held them, a clumsy blend of schooled grace and pure feeling, against himself.

“You want the craziest things.” He was trying, like a man trying to walk with a broken leg, to smile. “And I can’t imagine how to—but I’ll try.”

“Oh, Sarth.” What sweet thankfulness, to come into his arms as Alkhes had into mine, to rest in safety, however briefly, my head on his chest.

“Oh, Tellurith.” He smoothed my hair. “And now; what is it you want me to do?”

“I just thought—it was just an idea—”

“Just thought what?”

“We had this problem—”

“What problem?”

“I, ah— Tell me, can you shave someone else?”

“Naturally, we all learnt.” The hidden smile was dying. Too much like recall to that frivolous, pointless life. Then his voice changed. “You don’t mean—”

“Sarth, he’s broken an arm and three ribs and he’s been riding after us four days— Somebody has to do it! And I don’t know how and outlanders are funny about depending on women at the best of times, and I thought—I thought—it would be a start . . .”

His muscles jerked and I nearly cringed. I had feared Sarth in malice. I had never felt him approach rage.

“Forget it, it was stupid, I’ll think of something else . . .”

“No.” The anger checked. Then he sighed and let me release myself. “I’ll do it. You have enough to think about.”

I kissed him. He held me gently, but close. When I stood back this time, the bystanders read it as conclusion, and moved in from all directions. I did not see him walk away.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 1.

Journal kept by Sarth

He was so blasted small. I stamped into that tent ready to bite him in half and spit out the bits, and he was huddled up on the floor against a saddlebag. Like a twelve-year-old bridegroom, just brought into the Tower. So blasted small . . . .

He must have been half asleep. He felt me come in, jumped up, hit his arm—or the ribs—and doubled up. I grabbed him, down on my knees, before I thought. I’ve seen so many children come into the Tower. Little. Uprooted. Afraid.

“Steady,” I think I said. “It’s all right.”

We were staring, a foot apart. He has these enormous eyes. Far too big for a grown man. Black as pitch. A whole night sky, in one human face.

He knew me, without a doubt. He tried to straighten—or stand up, outland soldiers have pride but absolutely no wits. “Whoa,” I said. I had been prodding draught-bullocks all day. “I’ve seen Tellurith.”

The last time we met he had seemed twice my size. An avenger, a demon with a dagger who filled Tellurith’s rooms to the roof. And he threw me out. It should have been pleasant, to know we had exchanged boots.

I felt the bones in his shoulder move. Below its padding the faded roan infantry tunic bulked awry; the bandage round his ribs. His fingers clamped the bad arm’s wrist.

“What did she say . . . to you?”

The ribs had pinched his breath. It came out ragged. Masking the intonation. Telling me more about damage, and exhaustion, and being here alone, an exile, than Tellurith had explained.

I could have retorted, I imagine you know, or even, Don’t you know? I could have said, Another of Tellurith’s crazy ideas. She wants to marry us both. Or, She expects me to open gates with you. Somehow. But the first two were war-signals, and the next friends’ talk. And the last was franker than I could manage. Then.

We were still staring, all but nose to nose. The eyes had got bigger. Or the face had shrunk, under the beard-shadow, the bruise. A scrap of a man, hurt, tired, hunted into a corner. Cold. Afraid.

I had moved before I knew it, too. As if he were just another new, unkempt boy. I pushed the hair out of his eyes and drew my palm on down the black bristle on his jaw.

“She asked,” I said, “if someone could help you shave.”

He froze solid. I should think his very heart stopped. And in that moment, I understood.

Just as he took a great breath, and clutched his ribs and got out through it, “ . . . never know—how m-much . . .”

The ribs pinched him on the stammer, that came from his chattering teeth. The sense was clear as a flag. Relief; apology; thankfulness; gratitude, decently controlled.

I found the cameleer’s jacket they had given him, and put it round his shoulders. Outside it was quite dark, and the sound of Shia’s pots said supper was close. “It’s warmer out there,” I said, “though you may not believe it. And I could do with supper first.”

We did not wait for Tellurith. He was past keeping a House-head’s schedule, whose one certainty is Late. Azo, of all people, dour scar-cheeked troublecrew, cut up what meat Shia missed, so he fed himself. My own razor was in the camp gear. Imported ivory handle, chased Dhasdein steel. Shia let me thieve hot water. We went back inside, for the steadier light, he splashed water and worked up a lather one-handed. I took the razor, and gathered myself up.

And he shut his eyes and lifted his face like a child ready to be washed. Offering me, offering the razor, his unprotected throat.

* * *

Tellurith was back before we finished. A shadow against the coals, head tilted from the papers in her lap. Bronze-crinkle Craft plait, every hair etched by firelight, the high cheekbones and arrogant jaw. Features I can shape from memory, in the dark, in my sleep. Like the question, the anxiety, the dawning, vindicated, once more successful gleam in those narrow chestnut eyes.

“There you are.” Scrambling up to meet us, a hand on my chest, on his intact arm. A smile for me. For him a scrutiny, then a butterfly, multiply significant touch on the cheek.

And then to me, “Do you want the last hot water, before we turn down?”

Old House usage. Dim the qherrique, that was both light and heat, for the night. Not so subtle reminder that they had bathed, as I had not. Horrifying signal that she was going to throw us all in bed together. Right now.

I think I managed not to gulp. Hot water? I wanted a full, hour-long bath. I wanted skin softener and hair wash and perfume, a manicure, my eye make-up, a face-veil and jewelry, sheets on my bed. Not to wash and shave by guess behind a wagon in the cold and dark, then fall into dirty blankets with my hair still stinking of sweat. And not, Mother save us, with another man!

One is grateful, at times, for the discipline of the Tower. I was thankful, at least, that she waited for me by the coals rather than give him first possession of the tent. Even if she waited in his arms.

The tent was a Verrain subaltern’s, built for one man and his servant, and that only while he dressed. It was actually an honor that Tellurith had one, technically, to herself. Otherwise we would have bedded down in the big infantry shelter. Figure such antics under the eyes of Shia and Azo and Hanni and her husband, and the Mother knows who else.

The Tower taught me, long ago, the dance of entry and apportion in shared territory, but it is always so delicate. This one was damnably delicate. And I was so tired. So tired I sat down like a peasant on a pack-bag and left arrangements to Tellurith.

So it was my own fault we wound up with a blanket on the ground canvas under us, and two beneath the Dhasdein officer’s cloak atop. And Tellurith nearest the door—“in case there’s trouble in the night”—and me against the wind-side wall. And the third between us: on his side to protect his broken ribs, and his bad arm, if you please, pillowed on my chest. “Because you’re the right size, Sarth. And you don’t thrash about.”

It is true, she sleeps like a net-cork in a gale. And true too, though she does not know, that I have learnt to tender fragile bed-mates in my sleep. How many times, in the Tower, has a boy with homesickness or some direr fever ended in my bed?

Outside the Tower, rumor has some nasty words for it. And sometimes, they are true, whether from lust or loneliness—too often you sleep solitary, even with five wives—or from honest love.

Perhaps such shadow territory stretches beyond the Tower. Certainly, no boy inside it ever made such a fuss.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 1.

Meditations. Alkhes-Assandar

He was so damned big. I’d dropped off when they left me alone. Three nights huddled in ditches with the bridle over my arm . . . I was still on hunt alert. So I jumped up the minute the shadow moved and there he was, right on top of me. Ten feet tall.

And so damned handsome. Built big, but perfect shape. Long legs, broad shoulders, narrow hips. Face like a temple sculpture. Not pretty. A man’s model. And those cursed lion’s eyes.

I remember him from Amberlight, got up like an artist’s whore, all gold-dust and jewels and paint. The sod’s better-looking without. Even with his nails broken and his hair uncurled and axle grease all over his shirt.

I expected him to hit me. Or to snipe. He’s got a tongue like a Heartland poison dart. I don’t know why he shut up. Or why he touched me, but it scared me dumb. If I’d been less cold, and less damaged, and less—daunted—I would have hit out myself. There are plenty of those around the court. In Dhasdein. Even in Cataract, sometimes. And they seem to like my looks.

And then Tellurith had to put me in bed with him. Like a damned woman, plastered all over his chest.

I have been in bed with men before. Not at court. In the field, on picket, or a retreat, you can get caught without blankets. Or even a cloak. When a raid hits the caravan, and you wind up on a sandhill with your gear on a camel thirty miles away, in one of those freezing Verrain desert nights. Or you can have wounded, and sometimes, to keep warm’s their only chance.

But I do not, not, not expect to wind up beside a man who looks like the River-lord’s statue, with the woman I’m supposed to have married on my other side.

May I be hung if he doesn’t look better in bed than Tellurith as well. All that hair—longer than hers, and thicker—spread out over the saddlebags like black-bronze silk. Profile like a cursed—statue. Plenty of muscle to fill out the blankets. And of course he’d never dribble or break wind. I doubt the bastard so much as snores.

Not that I had a chance to find out. If the rest hadn’t done for me, Tellurith did. Dropped sleep-syrup in the last tea we had, waiting for—Sarth—to wash. I knew by my next morning mouth. But after that, I hardly got past, “I can’t sleep in there, wait, listen, Tellurith . . .”

And part of it, gods know, was the relief. Oh, gods, to have that pain stop. To rest a broken bone on something not too hard, not too soft, just the right height. And not have to move again. To know yourself back in friendly lines. Safe.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Tellurith’s Diary

The old poet was right, when she said that leaving your City is only to take it with you somewhere else. But even with it half a moon dead behind you, on what else do you pattern your life?

Which may be why, along with grief, and loss’s aftermath, and remembered ruin, not to mention wrestling these Mother-forsaken bullocks and more forsaken wagons along this most forsaken mule-track, I have had to break up a war tonight.

Two women. Two cutters. Cousins of Charras, my senior power-Crafter, married amiably ten years to the same man. Coming to blows, to woken cutter blades, over who should bed him first.

It must be memory that terrifies me so, to see a cutter woken like that. Memory of the great light-guns, that I designed, that Diaman and Keranshah built along with us, shearing through wood and metal and flesh and bone on the glacis of Amberlight. Of that sick jerk as the blade in my own hand met naked flesh. But to see those white beams clash in the twilight, and know they threatened my own kind . . .

I broke it up, of course. House-head skills, ingrained House discipline. A couple of bellows, and Azo and Zuri were there to back me. If they had not stopped.

If they had not stopped . . . Azo or Zuri with an arm gone, a thigh slagged, a foot cut off. If they had not stopped . . .

It will be better once we arrive. When we can shed the nightmare of pursuit, of fresh massacre along this pestilent bog-rut. When we can settle into the new life.

A relief to know we are expected; that it is all right—or as all right as three hundred strange mouths at the heel of autumn may be. The light signal came back today. I sent Iatha, House steward, with Hayras and Quetho, the closest I have to Craft-heads, and Desis: troublecrew, sometime raider, scout. All well, the signal said. Report follows. Desis will be riding back with it, firsthand information, right now.

* * *

A tidy enough village, it sounds. Forty to fifty permanent houses, perhaps four hundred souls. Mother bless, room to spare; quarters for the summer quarrymen. And a negotiable ascent. Better than this pig-wallow where we have had to shore every bridge; Desis is developing an engineer’s eye.

I could have sent a genuine one, but Alkhes is still not fit to sit a horse. And to judge from Desis’ words, I was wise.

“The Ruand, ah.” Hunkered on her heels, sipping the last tea by my fire. “Reckon she’s a bit of a character.” A pause. A shake of her alert, cropped, troublecrew head. “They stick to the old ways, up there.”

Troublecrew, so she will not warn me outright: Ruand, we are headed for the backwoods, where they make myths of Dhasdein and an ogre of Cataract. Where men’s rule has not merely never been threatened, but is still undreamt. Where newfangled revolutions might be more danger than they are worth.

I was considering that . . .

No. I was still refusing to consider that when, behind me, someone spoke.

“That water’s getting cold.”

The last hot water of the night. Saved with love’s care, with steely determination. Offered in Sarth’s dark velvet voice.

With Sarth himself hunched at my back, one hand thistledown-soft on my shoulder point.

From Alkhes it would have been nothing, but from Sarth? Bred and trained in the tower, in Amberlight, where men are taught from birth not to ask?

Six nights I had been sleeping with them both, too tired and too tense to think of anything more. After this news it would be worse. As he, with the remnants of that men’s gossip-net, would know.

The bath would warm me, the other would help me sleep. That too, he had long known.

The rest had to begin some time.

I got up, and offered him a hand. When he took it, I said, “You can come and scrub my back.”

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Meditations. Alkhes-Assandar

The bastard! The scurvy, sneaking, double-crossing whore!

I should have thought. Should have expected it. She said, Both of us. She took him back. He fought for her. She was with him while I—was blowing up, tearing down her life. She even loves the bastard. I can tell that. She has a right. She has every right!

But oh, gods, it hurts.

I thought I could manage it. Whatever happened, I have to wait. You can’t please yourself, let alone a woman, when every stray move folds you up like a busted tent. And I’m so tired. Not just the damage. Trying to stay on my horse, trying to make these stubborn, lamebrain, deaf-and-blind women do some things right—gods, with two pentarchs and some discipline, I could cut five days off this march. If I even had a sapper who’d pay attention at the creeks! But Zuri’s are the only ones who listen. Most are shapers or power-crew. They don’t know me, they don’t trust me, they damn well don’t like me. I betrayed their Head and wrecked their House. And blew up Amberlight.

And Tellurith, I could shake her, leaves me stuck with—him. Not enough he has to help me dress and shave and even eat. He heaves me on the blasted wagon. When things go wrong and I try to swing a pick for them—if the ribs catch, he has to pick me up!

I can bear with that. I can bear his nursemaiding. I can bear to sleep with him. But gods above, how dare the dung-eating bastard slip in and sleep with her!

I could swipe his head off. I could cut his guts out. I could kill him. One good kick in the throat.

But the look on her face. When they finally came in. Hand in hand. With that whore smirking from ear to ear. And Tellurith—not worried for once. That smile. That look.

Oh, gods, it hurts.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Journal kept by Sarth

In the Mother’s name, if I must endure exile, have I to suffer barbarity as well? Am I not perpetually unbalanced by a man who acts like a House-head and looks like an injured boy? Have I not the right, after shepherding him from every piece of mischief in the day’s march, to offer comfort to my own wife? And if, for the opulence of an upper level Tower room, with its cushions and rugs and drapes, the elegant artistry, the leisured music and conversation, all by the glow of the qherrique, I can substitute only a quick cold tumble in the dark, must I bear a ruffian’s tantrums at its end?

Bad enough when he refused to sleep between us that night. No explanation. No manners about it either. Mother, he could use a spell in the Tower. Worse when Tellurith went off early, without a word, so I had to help him dress. And when I offered it, he tore the shirt out of my hands.

I am Tower-bred. I said only, “What is it, Alkhes?”

“You slime!”

“What?”

“Bed her while I can’t—slip off with her—you cheating thief!”

No time for bewilderment, less for shock. Had he been whole, I would already have died. As he started for me, I said, “So predictable. Your only art.”

“You—!”

“And for me, one hand will be enough.”

It stopped him like a fist. Tellurith says I have a stiletto tongue.

“You might consider,” I was less angry but just as ashamed of myself, “what Tellurith wants.”

He was trying to get his breath. As if I had struck him in good truth.

“Will it please her, if you kick my face in? If we go brawling like a pair of dogs? Do you ever think about what she feels? Did you consider how she felt, last night?”

His lips moved, and nothing came out. If those eyes get any bigger, I was thinking, I will drown.

Blessed Mother, why did you curse me with Tower training? Why do I lack a soldier’s cruelty? A soldier’s callousness?

I took the long step forward to grasp his shoulder and said, “I mean the news Desis brought.”

There must be discipline in soldiery after all. He was still linen-white, but the lips, however stiffly, could move.

“What news?”

“The Iskans. The village. They’re traditionalists.”

“What?”

“That means women rule. There’ll be a matriarch.”

I might as well have told him camels could fly.

“So,” I said patiently, “she may well doubt folk who’ve decided to pull the Tower down. To let the men out. And put two of them in the Ruand’s tent.”

The lips moved. Maybe it was, “Oh.”

“Don’t you think, last night, Tellurith might have been a little—concerned—about that?”

The eyes had got bigger. Too big, far too black. I am a total fool as well as Tower-bred. I put both hands on his shoulders as if he were a compatriot, a cousin, a new young bridegroom. A friend.

“I didn’t mean to distress you.” At that moment, it was the truth. “I was thinking about her.”

He put the good hand to his side. There are times I have seen Tellurith do that. With just such a look on her face.

“I’m sorry.” Sometimes it is easier than you would imagine. “Now and then my words are sharp.”

His breath jerked, almost as if shaken into a laugh. Then he took the hand away. Looked up in my eyes and said, “No. You were right.”

I tightened my grip. Fine-twisted muscle, slender bones, steely tendons. Frail as his soldier’s pride. His exile’s confidence.

“I have to—”

He stopped. Took another sip of breath.

“We have to—sort this out.”

I let go. Sort what out? I wanted to say. You are an outlander, a killer, a barbarian. In Amberlight, no decent woman would put you in her Tower.

But we were not in Amberlight.

And you, said another, more accusing voice, have Tower skills, if he does not.

And you promised Tellurith: I’ll try.

“You are there for the woman,” I said. “That is what I learned. What she wants, when she wants. Be ready, be waiting. Be patient. Learn to read her wish. Learn about her friends, her work. Remember that they matter more to her. Never ask. Never importune. Always, put the woman first.”

Teach to learn, Sethar used to say, wisest of men, in my own youth. I seemed only to have struck this one dumb.

I picked up the shirt. He caught and checked my hand. The eyes were alive now. Enormous, but no longer dazed, sparking like midnight qherrique.

“You’re telling me this—you’re not telling me this because it’s what you want. But to explain how it was. Because you don’t understand me. But you do understand yourself.”

“No,” he read my eyes, “let me try . . . I was raised outside Amberlight. It’s—the quickest way to say it is: men come first.”

He produced a bleak little smile. “Yes, reverse everything you said. Well, almost everything. Women out here do have more freedom than you. But men . . .”

He paused, and frowned. “It doesn’t reverse properly. Because Tellurith’s always shared. But men out here—don’t share.”

I let the shirt fall. He gave a quick, jerky nod.

“I didn’t expect—I didn’t think I’d feel like that. I never meant to—unload it on you. On anyone. It just—hurt too much.”

He thought she was his property. No, he had been taught she was his property. His sole property. So his response, instilled as mine, had been the opposite.

“I thought I could handle it. But . . .”

I put a finger to his lips. Warmth, breath, the soul of him, alive under my touch.

“Let me try. It was a knee-kick, both sides.” The jerk the physicians tap out to test if your nerves are sound. “We were both at fault.”

His eyes spoke. I pressed the finger tight. Now, something within me said. You took one step to save yourself and another to rescue him. Take a third, for us both. For us all.

“I don’t understand you, yet. But I promised Tellurith. I will try.”

I took my hand away. He blinked.

“Try?”

“To make this—us—work.”

Something happened to his face. Then he put his own hand up, as if to feel my touch, on his mouth.

But he was still the outlander, the soldier. Among whom, I find, treaty terms and boundaries must be spelt out.

“So can we agree,” for an instant he shut his eyes, “that whatever—whoever—she wants, she gets?”

She has never, I did not say, operated on any other terms.

“And that we—let her make the choice?”

What would be different?

“And,” he swallowed, “that we don’t—compete?”

There I finally woke to sense.

“We can agree whatever we like. The question is, what does she think?”

He clapped his hand back over his face. I caught at it in alarm, and he lowered it, with another long, shaken breath.

“I keep forgetting. I keep fouling it up.” He looked up at me with eyes where rage and jealousy were weirdly entangled with guilt. “And I used to think you were a—a—”

“Clothes-horse?” Whatever was in my smile, he winced. “That you’re outland doesn’t make you a fool.”

He started to speak. Stopped. Then he shook his head.

“And the code you talk . . . I’ll try to remember that as well.”

Then he thrust out the good hand and looked me straight in the eye.

“We let her make the rules, then. We try—I’ll try—not to fight over her. Not to—lose my head again. Not to,” a wry, bitter smile, “put it off on you.”

What use to recall the Tower, where he would have learnt to manage all this, or to let it out mannerly, from birth? I took his hand. When he let go, I decided he was chastened enough for the risk. I picked up the shirt for the third time and enquired, “And now, would you consider getting dressed?”

Mother be blessed, he laughed.

* * *

Wits, then, despite being outlander. Sharp enough to learn, perhaps. Certainly to encourage me in idiocy. So at the first hold-up that day, when half a bridge-span’s edge caved in under Zariah’s bullock-cart, and he scampered down to embroil himself in the uproar, I dared to touch his arm.

“What the—!” He had spun so fast I jumped back myself. “Oh . . . Gods, be careful doing that!”

It takes no troublecrew to know a killer’s reflex. But he was past that already. “What is it—uh—”

A fresh cascade of diggers and riggers poured round us, halfway down the flattening track past the bridge bastion. Good solid Iskan stone, with dry grass, and shadow, at its foot.

Following me into that, wary, almost suspicious, he repeated, “What is it—ah—Sarth?”

Another giant step. One, pest on him, I could only match.

“Uh—Alkhes. May I suggest something?”

The eyes focused. The eyebrows flicked. A gesture down into the creek, where they were wading about, disputing and quarrelling, around the debris. “About that?”

“Um. Yes.”

He waited. He was going to listen. More than you can say for Zuri’s lot, whose best response is a courteous pat on the rump.

“Just let them get on with it. It may take time, but it’s what they need.”

The eyes sharpened. “Need?”

I was far outside decorum. Far beyond my place, to explain women to an outside man. “Ask Tellurith. I have to get back—”

“Wait just one moment!” He actually caught my sleeve. The eyes skewered me. “Need what?”

“Ask her. I can’t explain it. It’s not my place—”

“What do they need?”

“It’s not my business, Alkhes!”

“All right, I’m sorry.” He came the step back with me. I have never seen the general, or the outlander, or the Mother-forsaken, terrifying wits of him, so clear. “I’ll ask Tellurith. I’ll think about it. They need their way. And,” the eyes sharpened, “it isn’t mine.”

He came with me up the bank, back to Charras’ bullocks, which I was trying to help drive that day. He held cups when I heaved the water-jar down for her three children; boiled water, to keep them from disease as well as the creek. He listened as we talked. Settled beside me, quiet, and willing, attentive as any novice, and terrifying as a leashed tiger-cub, in the shade where we decided to wait.

He would have been an ornament to a Tower after all. He does not learn by questions. He listens, and looks.

And thinks.

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Tellurith’s Diary

“Tel, what is it that you—your folk—need to do, that I can’t help?”

He had waited for that precious after-dinner lull, with last reports made, trouble sorted, Iatha and even Hanni gone; the space before baths and men’s time, the time I have kept for myself. He sat on his heels, a slight, lithe shadow in the ember-glow; the falling wing of hair crossed his eyes with paler night. I slid a hand through it, living silk under my fingers, while I thought.

“Why do you ask?”

Darkness folded. A frown.

“When the bridge collapsed today. He . . .” An almost audible gulp. “ . . . Sarth—said I should stay out of it. That they ‘needed’ it.”

I did not exclaim, Sarth? Probably I will never know what happened this morning. But a truce was miracle enough.

“Alkhes . . . Caissyl.” Incongruous to love-name this one Sweetness, yes. Unwise to say, You’ve been talking. I’m so glad.

“You’re a soldier. A general. You’ve probably forgotten more about marches—and road-making—than we’ll ever know.” He did not trouble to nod. “You think I ought to use that; and I would. Except . . . do you remember the soap?”

The black brows came together. A moment’s pause. And then a softly indrawn breath.

“If a general wants to spoil the water, he can. No question. But you thought—remembered—considered—everyone else.”

Never, yet, have his wits failed me. Never, yet, have they failed to exceed my aim. But when I nodded, I felt the renewed frown.

“So what’s wrong with considering—trying to help?”

“Two things. First . . .” I held out a hand. He eeled closer, into my arm.

“First. You still try to help like a general. You want to—go in from the top. Give orders, arrange, direct things. Do it as clean and fast as anyone can.”

The hurt was clear as a cry. He had been so sure he was doing better, paying attention, thinking of other people. I gave his shoulder a little shake.

“The second thing . . . I’ve pulled them out of the City. Out of places, and crafts, and ranks that were settled, fixed, longer than their lives. And I’ve pulled down the towers. They have to fit the men in now, some way—altogether new. And the men have to fit. Do you know what Sarth’s gone through, just learning to swing a mallet? Have you seen his hands? And do you notice the way the women still have trouble hearing him? When he does have something to say?”

His head was bent, his eyes on the fire. After a moment he said very quietly, “Damn, how much more have I missed?”

“I doubt you could have helped that. Even with Zuri’s crew. Not yet. But . . .”

He turned to me this time. Swinging on his heels to put the good hand, light, if without its usual feather deftness, to the haft of my plait. But he did not urge, Go on.

“And there are all the—people who—died.”

Craft-heads, Navy captains, clan leaders. Mothers, sisters, daughters. All the gaps in the great web of kin and craft and custom that had been the House.

“They have to—put the House back together. Most of all . . . most of all, they have to do it from the bottom. You can’t tell them, even if it’s a better way. They have to do it for themselves.”

The coals spat. A palpably more bitter wind skirled round the tent. Elsewhere in camp people talked, cattle bawled, a baby cried.

“So your way of organizing—is to let them organize.”

He read my relaxation. His fingers flicked my plait, a tactile smile. “With a few gentle prods, and arrangements when they’re asked for. And godforsaken—endless—waits.”

Never have his wits failed me. And never have they failed to reach beyond my aim.

“But, Tel—if they—we—put it all back together, the old way—what will change?”

I could not help the little laughing gasp. “What!” Nor the yank on his hair. “Just why do you suppose, dangle, that you’re here at all?”

“Ouch! Tyrant . . . you mean it’ll shift, just having men out of the tower?”

“Hasn’t it?”

This time the silence was arrested. To break on a jerk half upright, a grunt. “The cursed—slime!”

“Eh?”

“Tel, this is—past crude. But who asked who, last night?”

My own muscles set. Then I said, “The woman comes first?”

His back transmitted the little, shaky sigh. “You are so quick . . .”

“Did you,” yet more indecent, but it had to be said, “did you two—argue?”

“I never got a chance.” A sharp little snort. “ I was ready to kill him, and he put five words between my ribs.” A more difficult breath. “And then he told me—his way—what you’ve been saying tonight.”

“You think he lied?”

“I didn’t think —I thought—the way he explained, it all made sense.” Now there was bitterness. The taste of betrayal. “And all the time—”

“No.” It was clear now as the ground-plan of Telluir House. “Not by intent. He knew I was upset. Worried. It was the one way he could help. To him, asking me . . .”

When I stopped, he finished for me. “Men never ask.”

However they are needed. I had been astonished, I recalled. And thought again, and shook my head.

“He’s changing too. He just hasn’t realized; hasn’t admitted it, yet.”

Silence, longer this time. Easier. Then a shift of position. A hand slid down my back; a silent, impudent, envisagable smile.

“If he can ask—so can I.”

* * *

The Diaspora. Week 2.

Journal kept by Sarth

Lucky, as outlanders do not say, that there are more ways of making love than one, and that Amberlight women know—expect—to use them all. So I daresay she made him happy, whatever he did for her. I do know I gave them time for it, fool that I am, trying to look busy, and easy, and dodge Azo’s eye, cowering over the deadened embers. Trying to guess, without prying indecency, when it would be safe to go inside.

Trying, harder than I have ever tried, not to let jealousy eat my heart in coals hotter than eternal fire.

I thought I could handle it, he said. So did I. I thought I was used to sharing. So I am. But not of my wives.

No doubt Outlanders would consider it barbaric, barbaric as the female harems they keep in Cataract. In fact, three of my five were dead: Sfina, head-Shaper, Wyen, second in the power shops, Khira, Captain on the Navy vessel Wasp. Lost in the River battles, killed defending the House. And Phatha, head of a Telluir sub-clan, chose to stay in Amberlight. And yes, now I can admit it, that though they shared my bed and my marriage, and I—worked—as hard to cushion and tend and pleasure each of them—

Even so, even when she left me, there was only one who mattered. Only one whose step I knew a stair away, only one I was ever waiting for.

At first it was the honor. Fourteen years old, fresh from flute and dancing school, crammed with the economics and politics of the River as of Amberlight, all the knowledge a man must carry, to understand, to sustain the woman’s talk, and never, never flourish for yourself—and Sethar walked in, that bright, sharp spring morning, with grandmother Zhee in person, upright and keen-edged as a blade in her plain leggings, the eccentric silver-worked black coat. The eyes, keener than any stiletto point, running over me as I stand, just dismounted from the vaulting horse, heart plunging, ribs heaving, but instinctively, reflexively, struggling for the perfect pose. Her slow, yet far sharper drawl. “You think he’ll do us grace.”

To me, as ever, unreadable. But for all his skill, Sethar cannot hide from me. My heart too leaps into my throat.

“Ma’am.” So calm, so deferent, so perfectly disciplined, the model of my life. “This is our best.”

She prickles me with that stare again. Then puts up the stiletto points, and frightens all excitement out of me. “We have a marriage offer,” she says. “From Telluir House.”

Not merely from Telluir House, ally, neighbor, glamorous, notorious, the Thirteen’s scandal and cynosure. From the Head of Telluir House.

How many nights was it that Sethar had, like a homesick baby, to sing me to sleep? How many mornings, like a woman pregnant, did I spend throwing up? Mother, when they brought me in the great House doors, double-swathed in the silk trousers, the gem-embroidered coat and shirts and face-veil and the great diaphanous outer cloak that took the summer breeze like a huge saffron flame—how did I keep my legs straight, and my heart unburst, and breath in my throat? When we reached the courtyard. And there at the Tower foot, she took my hand. And smiled at me. Tellurith. Brilliant as a star in gold-worked ivory, in the heirloom jewels of the House. My dream. My terror. My wife.

Of course, as Sethar had drummed into me, I did not have to finish the ordeal by fire that night. At fourteen, barely two years younger than she, I was not expected to play the man for another year or two. Time to learn my place, my House, my Tower. To be confident and calm. So the night she did come, I could offer my Ruand her husband’s suite, and a light supper, and music, and some intelligent comments, and even, fore-warned by the Steward at mid-afternoon, manage to look my best.

And later, to do my best. And best of all, to meet, to match—to be her heart’s desire.

The good times—no, I cannot think of them. I will not think of the bad times. I will not remember how it felt, when they told me about him. Mother preserve me, do you know how it is to hold your face still, while dogs eat out your bowels? While every fiber of you cries, Oh, Mother, only let me die?

But I will write this down, as I never could, never would have dared before. Men’s trivial records, men’s paltry thoughts. Huddled here by the coals with an old slate and Hanni’s chalk-end, where no-one would look for such a thing. I will set it down, to cement the vow.

I survived all that. I can—I will—survive this.

* * *