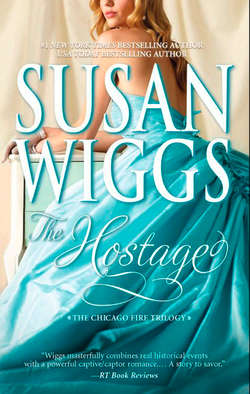

Читать книгу The Hostage - Сьюзен Виггс - Страница 8

Chapter One

Оглавление“What’s the matter with Deborah?” asked Phoebe Palmer, standing in the middle of a cluttered suite of rooms at Miss Emma Wade Boylan’s School for Young Ladies. Lacy petticoats and beribboned unmentionables littered the divans and ottomans of the fringed, beaded and brocaded salon. “She won’t even let her maid in to attend her,” Phoebe added.

“I’ll see what’s keeping her.” Lucy Hathaway pushed open the door to an adjoining chamber. Deborah’s dress, which she had worn to Aiken’s Opera House the previous night, lay slumped in a heap of tulle and silk on the floor. A mound of sheets lay scattered over the bed, while the smell of expensive perfume and despair hung in the air.

“Deborah, are you all right?” Lucy asked softly. She went to the window, parting the curtain to let in a bit of the waning evening light. In the distance, some of the taller buildings and steeples of distant Chicago stabbed the horizon. The sky was tinged dirty amber by the smoke and soot of industry. But closer to Amberley Grove, the genteel suburb where the school was located, the windswept evening promised to be a lovely one.

“Deborah, we’ve been pestering you for hours to get ready. Aren’t you coming with us tonight?” Lucy persisted. Though the engagement bore the humble name of an evangelical reading, everyone knew it was simply an excuse for the cream of society to get together on the Sabbath. Though weighty spiritual issues might be discussed, lighter matters such as gossip and romance would be attended to with appropriate religious fervor. Tonight’s particular social event had an added drama that had set tongues to wagging all week long. The intensely desired Dylan Kennedy was looking for a wife.

“Please, dear,” Lucy said. “You’re scaring me, and ordinarily nothing scares me.”

Huddled on the bed, Deborah couldn’t find the words to allay her friend’s concern. She was trying to remember what her life had been like just twenty-four hours ago. She was trying to recall just who she was, tallying up the pieces of herself like items in a ledger book. A cherished only daughter. Fiancée of the most eligible man in Chicago. A privileged young woman poised on the threshold of a charmed life.

Everything had fallen apart last night, and she had no idea how to put it all back together.

“Make her hurry, do,” Phoebe said, waltzing in from the next room with a polished silk evening dress pressed to her front. “Miss Boylan’s coach will call for us in half an hour. Imagine! Dylan Kennedy is finally going to settle on a wife.” She preened in front of a freestanding cheval glass, patting her glossy brown hair. “Isn’t that deliciously romantic?”

“It’s positively barbaric,” said Lucy. “Why should we be paraded in front of men like horses at auction?”

“Because,” Kathleen O’Leary said, joining them in Deborah’s chamber, “Miss Boylan promised you would all be there. Three perfect young ladies,” she added with a touch of Irish irony. She reached for the curtain that shrouded the bed. “Are you all right, then, miss?” she asked. “I’ve been trying like the very devil to attend to you all day.” The maid put out a pale, nervous hand and patted the miserable mound of blankets.

Deborah felt assaulted by her well-meaning friends. She wanted to yell at them, tell them to leave her alone, but she had no idea how to assert her own wishes. No one had ever taught her to behave in such a fashion; it was considered unladylike in the extreme. She shrank back into the covers and pretended not to hear.

“She doesn’t answer,” Lucy said, her voice rising with worry.

“Please, Deborah,” Phoebe said. “Talk to us. Are you ill?”

Deborah knew she would have no peace until she surrendered. With slow, painstaking movements, she made herself sit up, leaning against a bank of Belgian linen pillows. Three faces, as familiar as they were dear to her, peered into hers. They looked uncommonly beautiful, perhaps because they were all so different. Blackhaired Lucy, carrot-topped Kathleen and Phoebe with her light brown curls. Their faces held the winsome innocence and anticipation Deborah herself had felt only yesterday.

“I’m not ill,” she said softly, in a voice that barely sounded like her own.

“You look like hell,” Lucy said with her customary bluntness.

Because I have been there.

“I’ll send for the doctor.” Kathleen started toward the door.

“No!” Deborah’s sharp voice stopped the maid in her tracks. A doctor was unthinkable. “That is,” she forced herself to say, “I assure you, I am not in the least bit ill.” To prove her point, she forced herself out of bed and stood barefoot in the middle of the room.

“Well, that’s a relief.” With brisk bossiness, Phoebe took her hand and gave it a friendly, aggressive tug. Deborah stumbled along behind her and stepped into the brightly lit salon.

“I imagine you’re simply overcome because you’ll be a married woman a fortnight from now.” Phoebe dropped her hand and smiled dreamily. “You are so fabulously lucky. How can you keep to your bed at such a magical time? If I were engaged to the likes of Philip Ascot, I should be pacing the carpets with excitement. The week before my sister married Mr. Vanderbilt, my mother used to joke that she needed an anchor to keep her feet on the ground.”

Deborah knew Phoebe didn’t mean for the words to hurt. Deborah was a motherless daughter, the saddest sort of creature on earth, and at a time like this the sense of loss gaped like an unhealed wound. She wondered what a young woman with a mother would do in this situation.

“So,” Lucy said, “let’s hurry along. We don’t want to be late.”

Through a fog of indifference, Deborah surveyed the suite cluttered with combs, atomizers, lacy underclothes, ribbons, masses of petticoats—a veritable explosion of femininity. It was the sort of scene that used to delight her, but everything was different now. Suddenly these things meant nothing to her. She had the strangest notion of being encased in ice, watching her friends through a wavy, frozen wall. The sense of detachment and distance hardened with each passing moment. She used to be one of the young ladies of Miss Boylan’s famous finishing school, merry and certain of her place in the glittering world of Chicago’s debutantes. It all seemed so artificial now, so pointless. She felt alienated from her friends and from the contented, foolish girl she used to be.

“And what about you, dear Kathleen?” Phoebe asked, aiming a pointed glance at the red-haired maid. Phoebe took every chance to remind Kathleen that she was merely the hired help, there at the sufferance of more privileged young women like herself. “What do you plan to do tonight?”

Kathleen O’Leary’s face turned crimson. She had the pale almost translucent skin of her Irish heritage, and it betrayed every emotion. “You’ve left me a fine mess to be tidying up, miss. And won’t that keep me busy ‘til cock-crow.” Saucy as ever, she exaggerated her brogue on purpose.

“You should come with us, Kathleen.” Lucy, whose family had raised her to be a free thinker, didn’t care a fig for social posturing, but she knew that important people would be attending. The politicians, industrialists and social reformers were valuable contacts for her cause—rights for women.

“Really, Lucy,” scolded Phoebe. “Only the best people in town are invited. Dr. Moody’s readings are strictly for—”

“The invitation was extended to every young lady at Miss Boylan’s,” Lucy, who was both wealthy and naive enough to be an egalitarian, reminded her.

“Stuff and nonsense,” Kathleen said, her blush deepening.

“Perhaps you should attend,” Phoebe said, a calculating gleam in her eye. “It might be fun to surprise everyone with a lady of mystery.”

The old Deborah would have joined in the ruse with pleasure. Lively, intelligent Kathleen always added a sense of fun to the sometimes tedious routine of social climbing. But it was all too much to think about now, and she passed a shaking hand over her forehead. The celluloid hairpins she hadn’t bothered to remove last night exaggerated the headache that made her grit her teeth. The pain hammered so hard at her temples that the pins seemed to pulse with a life of their own.

“Phoebe’s right, Kathleen,” Lucy was saying. “It’ll be such fun. Please come.”

“I’ve not a stitch to wear that wouldn’t mark me as an imposter,” Kathleen said, but the protest failed to mask the yearning in her voice. She had always harbored an endless fascination with high society.

“Yes, you have.” Deborah forced herself out of her torpor. “You shall wear my new dress. I won’t be needing it.”

“Your Worth gown?” Phoebe demanded. At her father’s insistence, Deborah’s gowns all came from the Salon de Lumière in Paris. “For mercy’s sake, you’ve never even worn it yourself.”

“I’m not going.” Deborah kept her voice as calm as she could even though she felt like screaming. “I must go into the city to see my father.” She wasn’t sure when she had made the decision, but there it was. She had a matter of utmost importance to discuss with him, and she could not put it off any longer.

“You can’t go into the city tonight,” Phoebe said. “Don’t be silly. Who would chaperone you?”

“Just come with us,” Lucy said, her voice gentle. “Come to the reading, and we’ll take you to see your father afterward. Philip Ascot will be in attendance, won’t he? He’ll be expecting you. What on earth shall we tell him?”

The name of her fiancé rushed over Deborah like a chill wind. “I’ll send my regrets.”

“You aren’t yourself at all.” Lucy touched her arm, her light brush of concern almost powerful enough to shatter Deborah. “We shall go mad with worry if you don’t tell us what’s wrong.”

Phoebe stuck out her foot so Kathleen could button her kid leather boot. “Was it last night’s opera? You were fine when you left, but you stayed in bed all day long. Didn’t you like Don Giovanni?”

Deborah turned away, a wave of nausea rolling over her. The notes of the Mozart masterpiece were forever burned into her.

“It’s your bloody flux, isn’t it?” Kathleen whispered, ignoring Phoebe’s boot. “You’ve always suffered with the heavy pains. Let me stay behind and fix you a posset.”

“It’s not the flux,” Deborah said.

Lucy planted her palm flat against the door. “This isn’t like you. If something’s wrong, you should tell us, dear.”

Nothing’s wrong. She tried to eke out the words, but they wouldn’t come, because they were a lie. Everything was wrong and nothing could ever be the same. But how did she explain that, even to her best friends?

“It’s of a private nature,” she said faintly. “Please. I’ll explain it all when I return.”

“Oh, so you’re going to be mysterious, are you?” Phoebe sputtered. “You’re just trying to make yourself the center of attention, if you ask me.”

“No one asked you,” Lucy said wearily.

Phoebe sputtered some more, but no one was listening. Though she had come up through school with the rest of them, Phoebe had set herself apart from the others. Nearly as rich as Deborah and nearly as blue-blooded as Lucy, she had concluded that the two “nearlys” added up to much loftier status than her friends enjoyed. She was a terrible and unrepentant snob, generally benign, though her remarks to Kathleen O’Leary sometimes brandished the sharp edge of malice. Phoebe alone understood that one did not simply abandon an exclusive social event. But this merely proved the inferiority of a girl like Deborah Sinclair. New-money people simply didn’t understand the importance of attending the right sort of functions with the right sort of people.

“I’d best go ring for my driver,” Deborah said.

Lucy moved away from the door. “It won’t be the same without you.”

Deborah bit her lip, afraid that the sympathy from her best friend would break through the icy barrier she had painstakingly erected between control and madness. “Help Kathleen with the gown,” she said, hoping to divert everyone’s attention to the masquerade.

After sending for her coach, Deborah buttoned on a simple blue serge dress and tugged a shawl around her shoulders. Pushing her feet into Italian kid leather boots, she didn’t bother with the buttoning. Instead, she wound the ribbons haphazardly around her ankles and then jammed on a hat.

In the main salon, the others dressed more carefully. Eyes shining with forbidden pleasure, Kathleen stepped into the French gown, her homespun bloomers disappearing beneath layers of fancy petticoats. The gown of emerald silk and her Irish coloring gave her the look of a Celtic princess, and her face glowed with an excitement Deborah could no longer share.

Before leaving, Deborah stepped back and surveyed the scene, seeing it for the first time through the eyes of an outsider. Over her father’s protests she had left his opulent, gilded mansion for the solid gothic halls of Miss Boylan’s. Her father believed the very best young ladies were educated at home. But once he learned a Hathaway and a Palmer would be in attendance, he had relented and allowed Deborah to complete her education with finishing school. She looked with fondness upon Lucy, Kathleen and Phoebe, who were her closest companions and sometimes, she thought, her only friends. The four of them had shared everything—their hopes and dreams, their broken hearts and romantic triumphs.

Finally Deborah had encountered something she could not share with her friends. She could not. It was too devastating. Besides, she must tell her father. She must. Please God, she prayed silently. Let him understand. Just this once.

“Have a wonderful time this evening,” she said, her hand on the door handle. “I shall want to hear all about Kathleen’s debut when I return.” She forced the words past a throat gone suddenly tight with terror.

Kathleen rushed to the door. “Miss Deborah, are you certain that—”

“Absolutely.” The word was a mere gust of air.

“Let the poor thing go,” Phoebe said in a distracted voice. She lifted her arm with the sinuous grace of a ballerina and drew on a silken glove. “If you stand around arguing all evening, we’ll be late.”

She and Lucy launched into a squabble over how Kathleen should wear her hair, and Deborah took the opportunity to slip out into the tall, cavernous hall and down to the foyer, where her driver waited. Outside, she saw the school’s large, cumbersome rockaway carriage being hitched to four muscular horses. The school crest adorned the black enamel doors.

Deborah’s private Bismarck-brown clarence, with its gleaming glass panes front and rear, waited at the curb. Thanks to her father’s habit of flaunting his wealth, the expensive vehicle, with its experienced driver and Spanish coach horse, was always at her disposal. Within a few minutes, she was under way.

She gripped a leather strap at the side of the interior of the coach, bracing herself against the rocking motion. As they pulled away from the school, with its ponderous, pretentious turrets and wrought iron gates, she felt like Rapunzel escaping her tower prison. Small farms sped past, squat houses hugged low against the prairie landscape of withered orchards and wind-torn cornfields. Lights glimmered in windows and the sight of them pierced her. She pictured the families within, gathering around the table for supper. She had only seen such families from afar, but imagined they shared an easy intimate warmth she had never felt growing up in the cold formality of her father’s house.

She cast away the yearning. All her life she had enjoyed the advantages most women never dared to dream about. Arthur Sinclair had crafted and aligned his daughter’s future with the same precise attention to detail with which he put together his business transactions. His rivals vilified him for his aggression and ambition, but Deborah knew little of commerce. Her father preferred it that way.

The drive into Chicago was swift. Jeremy, who had served as her personal driver since she was three years old, drove expertly through the long, straight roads that crisscrossed the city. Jeremy lived in a garden cottage along the north branch of the Chicago River. He had a plump wife and a grown daughter who had recently wed. Deborah wondered what Jeremy did when he returned home to them, late at night. Did he touch his sleeping wife or just light a lamp and look at her for a moment? Did she awaken, or sigh in her sleep and turn toward the wall?

Deborah knew she was using her meandering thoughts to keep her mind off the ordeal to come. She shifted restlessly on the seat and cupped her hands around her eyes to see through the glass as Chicago came into view. Ordinarily, the air was cool closer to the lake, but this evening, the day’s heat hung well past sundown.

The whitish fuzz of gaslight illuminated the long, straight main thoroughfares. The coach crossed the river, rolling past the elegant hotel where the reading party was to take place. Well-dressed people were already gathering. Liveried doormen rushed to and fro beneath a scalloped canvas awning that flapped in a violent wind. Huge potted shrubs flanked the gilt-and-glass doorway, and inside, a massive chandelier glowed like the sun. The gilded cage of high society was the only world Deborah had ever known, yet it was a world in which she no longer felt safe. She couldn’t imagine herself walking into the hotel now.

Traditionally set for the second Sunday of the month, the lively readings and discussions ordinarily held a delicious appeal for her. She loved seeing people dressed in their finery, happily sipping cordials as they laughed and conversed. She loved the easy pleasures of glib talk and gossip. But last night the magic had been stolen from Deborah.

No matter. Tonight she vowed to reclaim her soul.

She shivered, knowing that skipping the social engagement was only the first act of defiance she would commit tonight. She had never before carried out a rebellion, and she didn’t know if she could accomplish it.

As the carriage wended its way up Michigan Avenue, Jeremy had to slow down before an onslaught of pedestrians, drays, teams and whole family groups. They seemed to be heading for the Rush Street bridge that spanned the river. Despite the lateness of the hour, crowds had gathered at the small stadium of the Chicago White Stockings.

Rapping on the curved windshield, Deborah called out, “Is everything all right, Jeremy?”

He didn’t answer for a few moments as he negotiated the curve toward River Street, heading for the next bridge to the west. They encountered more crowds, bobbing along in the scant illumination of the coach lamps. Deborah twisted around on the cushioned bench to look through the rear window. The pedestrians were, for the most part, a well-dressed crowd, and though no one dawdled, no one hurried, either. They resembled a dining party or a group coming out of the theater. Yet it seemed unusual to see so many people out on a Sunday night.

“They say there’s a big fire in the West Division,” Jeremy reported through the speaking tube. “Plenty of folks had to evacuate. I’ll have you home in a trice, miss.”

She knew Kathleen’s family lived in the West Division, where they kept cows for milking. She prayed the O’Learys would be all right. Poor Kathleen. This was supposed to be an evening of pranks, pretenses and fun, but a big fire could change all that.

She wondered if Dr. Moody’s lecture would be canceled because of the fire. Probably not. The Chicago Board of Fire boasted the latest in fire control, including hydrants, steam pump engines and an intricate system of alarms and substations. Many of the stone and steel downtown buildings were considered fireproof. The city’s elite would probably gather in the North Division to gossip the night away as the engineers and pumpers brought the distant blaze under control.

She stared out at the unnatural bloom of light in the west. Her breath caught—not with fear but with wonder at the impressive sight. In the distance, the horizon burned bright as morning. Yet the sky lacked the innocent quality of daylight, and in the area beyond the river, brands of flame fell from the sky, thick as snow in a blizzard.

Apprehension flashed through her, but she put aside the feeling. The fire would stop when it reached the river. It always did. The greater problem, in Deborah’s mind, was getting her father to understand and accept her decision.

The coach rolled to a halt in front of the stone edifice of her father’s house. Surrounded by yards and gardens, the residence and its attendant outbuildings took up nearly a whole block. There was a trout pond that was used in the winter for skating. The mansion had soaring Greek revival columns and a mansard roof, fashionably French. A grand cupola with a slender lightning rod rose against the sky. A graceful porch, trimmed with painted woodwork, wrapped around the front of the house, with a wide staircase reaching down to the curved drive.

“You’re home, miss,” Jeremy announced, his footsteps crunching on the gravel drive as he came to help her down.

Not even in a moment of whimsy had Deborah ever thought of the house on Huron Avenue as a home. The huge, imposing place more closely resembled an institution, like a library or perhaps a hospital. Or an insane asylum.

Squelching the disloyal thought, she sat in the still swaying carriage while Jeremy lowered the steps, opened the door and held out his hand toward her. Wild gusts of wind pushed dead leaves along the gutters and walkways.

Even through her glove she could feel that Jeremy’s fingers were icy cold, and she regarded him with surprise. Despite a studiously dispassionate expression, a subtle tension tightened his jaw and his eyes darted toward the firelit sky.

“You’d best hurry home to your wife,” she said. “You’ll want to make certain she’s all right.”

“Are you sure, miss?” Jeremy opened the iron gate. “It’s my duty to stay and—”

“Nonsense.” It was the one decision she could make tonight that was unequivocal. “Your first duty is to your family. Go. I would do nothing but worry all night if you didn’t.”

He sent her a grateful bob of his head, and as he swept open the huge, heavy front door for her, the braid on his livery cap gleamed in the false and faraway light. Deborah walked alone into the vestibule of the house, feeling its formidable presence. Staff members hastened to greet her—three maids in black and white, two house-men in navy livery, the housekeeper tall and imposing, the butler impeccably dignified. As she walked through the formal gauntlet of servants, their greetings were painstakingly respectful—eyes averted, mouths unsmiling.

Arthur Sinclair’s servants had always been well-fed and -clothed, and most were wise enough to understand that not every domestic in Chicago enjoyed even these minor privileges. To his eternal pain and shame, Arthur Sinclair had once been a member of their low ranks. So, though he never spoke of it, he understood all too well the plight of the unfortunate.

She prayed he would be as understanding with his own daughter. She needed that now.

“Is my father at home?” she inquired.

“Certainly, miss. Upstairs in his study,” the butler said. “Would you like Edgar to announce you?”

“That won’t be necessary, Mr. Marlowe. I’ll go right up.” She walked between the ranks of silent servants, surrendering her hat and gloves to a maid as she passed. She sensed their unspoken questions about her plain dress and shawl, the disheveled state of the hair she had not bothered to comb. The stiff, relentless formality was customary, yet Deborah had never enjoyed being the object of the staff’s scrutiny. “Thank you,” she said. “That will be all.”

“As you wish.” Marlowe bowed and stepped back.

With a flick of her hand and a jingle of the keys tied at her waist, the housekeeper led the others away. Through the doors that quickly opened and shut, Deborah could see that valuables were being packed away into trunks and crates. A precaution, she supposed, because of the fire.

Standing alone in the soaring vestibule, with its domed skylight three storeys up, Deborah immediately and unaccountably felt cold. The house spread out in an endless maze of rooms—salons and seasonal parlors, the music room, picture gallery, dining room, ballroom, conservatory, guest suites she had never counted. This was, in every sense of the word, a monument to a merchant prince; its sole purpose to proclaim to the world that Arthur Sinclair had arrived.

Dear God, thought Deborah. When did I grow so cynical?

Actually, she knew the precise moment it had happened. But that was not something she would reveal to anyone but herself.

Misty gaslight fell across the black-and-white checkered marble floor. An alabaster statue of Narcissus, eternally pouring water into a huge white marble basin situated in the extravagant curve of the grand staircase, greeted her with a blank-eyed stare.

Beside the staircase was something rather new—a mechanical lift. In principle it worked like the great grain elevators at the railroad yards and lakefront. A system of pulleys caused the small car to rise or lower. Her father had a lame leg, having been injured in the war a decade ago, and he had a hard time getting up and down the stairs.

To Deborah, the lift resembled a giant bird cage. Though costly gold-leaf gilding covered the bars, they were bars nonetheless. The first time she stood within the gilded cage, she had felt an unreasoning jolt of panic, as if she were a prisoner. The sensation of being lifted by the huge thick cables made her stomach lurch. After that first unsettling ride, she always chose to take the stairs.

The hand-carved rail of the soaring staircase was waxed and buffed to a high sheen. Her hand glided over its satisfying smoothness, and she remembered how expert she had been at sliding down this banister. It was her one act of defiance. No matter how many times her nanny or her tutor, or even her father, reprimanded her, she had persisted in her banister acrobatics. It was simply too irresistible to prop her hip on the rail, balance just so at the top, then let the speed gather as she slid down. Her landings had never been graceful, and she’d borne the bruises to prove it, but the minor bumps had always seemed a small price to pay in exchange for a few crazy moments of a wild ride.

Unlike so many other things, her father had never been able to break her of the habit. He governed her sternly in all matters, but within her dwelt a stubborn spark of exuberance he had never been able to snuff.

Deborah started up the stairs. The study housed Arthur Sinclair’s estate offices, and he worked there until late each night, devoting the same fervor to his business as a monk to his spiritual meditations. He regarded the accumulation of wealth and status as his means to salvation. But there was one thing all his money and influence could not buy—the sense of belonging to the elite society that looked down on his kind. Acquiring that elusive quality would take more than money. For that he needed Deborah.

She shuddered, though the house was overly warm, and took the steps slowly. She passed beautifully rendered oil portraits in gaudily expensive gold-leafed frames. The paintings depicted venerable ancestors, some dating back to the Mayflower and further. But the pictures were of strangers plucked from someone else’s family tree. She used to make up stories about the stern-faced aristocrats who stared, eternally frozen, from the gleaming frames. One was an adventurer, another a sailor, yet another a great diplomat. They were all men who had done something with their lives rather than living off the bounty of their forebears.

She would never understand why her father considered it less honorable to have earned rather than inherited a fortune. She had asked him once, but hadn’t understood his reply. “I wish to have a feeling of permanence in the world,” he had said. “A feeling that I have acquired the very best of everything. I want to achieve something that will last well beyond my own span of years.”

It was a mad quest, using money to obtain the things other families took generations to collect and amass, but he regarded it as his sacred duty.

She reached the top of the stairs and paused, her hand on the carved newel post. She glanced back, her gaze following the luxurious curve of the banister. Through the inlaid glass dome over the entryway, an eerie glow flickered in the sky. The fire. She hoped the engineers would get it under control soon.

But she forgot all about the fire on the other side of the river as she started down the hall toward her father’s study. A chill rippled through her again, carrying an inner warning: One did not contradict the wishes of Arthur Sinclair.