Читать книгу The Valley Beyond - T. A. Nichols - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter V

Lucía and Isabella were two girls who truly relished being with each other. Lucía was coeval with Isabella, and the two shared much in common. However, Isabella was a bit shyer, soft-spoken, and a noncomplainer; and her oval face and soft brown eyes, along with a small frame, which she covered with her long brown hair, gave the impression of a fragile and weak child.

As the two girls spent more time with each other, Yamina also became Isabella’s tutor on occasion. Yamina offered instruction and was very strict on matters that concerned courtesy and how to manage household staff. The girls learned to stand erect and not to slouch, how to properly curtsy, and the art of the dance, which the two girls enjoyed on their own.

Despite their chores and instruction, they did manage to spend time with each other; they talked and giggled in their shared bed until they fell asleep. However, their favorite pastime was climbing the steps of the tallest tower in Segoia to look out over the countryside. From the tower, they could see the city below and the sparsely wooded grassy plain that stretched to the mountains on the horizon. As they turned, they could also see the peasant village in the distance and to the left of the village, across the road, the family vineyard. As they looked down from the tower, they could see the cliff that the city rested upon and the long drop to the River Duero below.

On occasion, Lucía would spend time at the castle of Gustavo, the home of Isabella. The castle was much smaller than Lucía was accustomed to, as it had only one tower to the left of the castle wall and a thick oak door that led to the courtyard; it was high enough for a man who sat on a horse to pass through. Below, to the left, outside the living quarters, was a dry riverbed that meandered by the castle wall, which was filled with water in the late winter and spring but dry in the summer on the hot dry, dusty plain. Down the road beyond the castle lay the town village.

While at Gustavo, Doña Teresa, Isabella’s mother, would also instruct both Lucía and Isabella on how to properly manage a household staff and how to act as host to notables who attended court. She was a very kind soul with an easy disposition and, when time permitted, would laugh and play with the children, at which time her brown eyes would light up, along with a wide smile from ear to ear. Lucía loved Doña Teresa, who became like a surrogate mother and a wonderful role model for Lucía to follow. Lucía also discovered that Doña Teresa had been one of her mother’s best friends.

One day, Lucía and Isabella were seated, doing their lessons with Yamina, when a messenger from Gustavo presented Isabella with a message from her mother. Isabella broke the wax seal and, with Yamina’s help, read the message. The message instructed Isabella to pack her clothes and be ready to leave in two days as the family had received a personal invitation from King Sancho to visit her relatives in Portugal.

“Do you wish me to wait for a return message, mi señora?’” asked the messenger, who addressed Isabella.

“Tell Mama that I will be ready,” said Isabella sadly.

“Very well,” said the messenger, who then turned and left the room.

“How long will you be away?” asked Lucía, who pouted at the prospect of the loss of her friend for quite some time.

“I do not know. Mama did not say how long.” Isabella was sad at the prospect of having to leave her friend but was also heartened to be going on an adventure. “Don’t be sad, Lucía. I will be back in several fortnights, and then I will tell you all about my time in Portugal.”

Lucía was very concerned, as she had heard stories at court about the hazards of traveling and overheard her father tell a visiting knight to be careful, as trouble was beginning between Portugal and Castile.

Lucía helped Isabella pack her trunks, but she was still concerned about the hazards she might encounter en route to Portugal.

The day of dread finally arrived, when Isabella’s parents appeared with a long entourage of wagons loaded with supplies and servants. The entourage was accompanied by twelve soldiers who wore over their coat of chain mail a surcoat that displayed the coat of arms of Gustavo: three silver swords lying on top of one another on a dark-blue background. Each soldier was fully armed and carried a lance with a dark-blue pennant, which was flying in the breeze. Such an impressive display had not been seen in Segoia for quite some time.

Along with Lucía were Don Fernando, Captain Gómez, and Father Piña, all on hand to welcome Don Alfonso Coronado and Doña Teresa and to wish them well on their long trip to Portugal.

Isabella was torn between having an adventure and staying with Lucía but really had no choice in the matter. Lucía broke down in tears and found it difficult to say goodbye to her best friend and confidante, but Doña Teresa embraced Lucía, comforted her, and told her that they would only be gone for no more than six to eight fortnights. She promised Isabella would write to her about her adventures.

The area in front of the palace became busy as servants hurried to bring down Isabella’s trunks from Lucía’s bedchamber. Once the trunks were packed onto a wagon, the entourage was ready to leave, but not before Father Piña gave a blessing for a safe journey. Isabella then gave her final embrace to a sniffling Lucía, who once again made Isabella promise to write. Isabella climbed into the wagon and waved goodbye. Then the entourage started to leave the palace grounds into the city, through the city gates, and to the horizon beyond. Lucía ran to the tower, where the two girls would often be found, and watched as the cortege disappeared into the horizon.

More than two fortnights had passed before Lucía received her first letter from Isabella. Lucía broke the seal and started to read the letter, proud of the fact that she could now read with only a little help from Yamina or her father.

“Papa,” yelled Lucía as she ran into her father’s study outside his bedchamber, “I have a letter from Isabella.” Lucía tried to catch her breath. “A messenger brought it from Coimbra, and I read it with only little help from Yamina.”

“Good for you, mi pequeño sol. What did Isabella say in the letter?” asked Don Fernando, seated in front of his worktable.

“Isabella said that the journey went smooth but had some difficulty in crossing the mountains, but everyone is okay. One night, several Knight Templars joined them for supper but left early the next morning for Jerusalem. When they arrived in Coimbra, they were greeted by family members and the next day met King Sancho. They had a large welcome banquet at an uncle’s castle outside of Coimbra. They will be going to visit another uncle and more cousins in Lisbon soon. She remembers us in her prayers at night and hopes all is well with us. The letter is signed Isabella.”

Despite the letter, Lucía still missed Isabella, as they had become very close and their friendship had run deep. Lucía would often lie awake at night in wonderment of what adventures Isabella might have had during the day, until sleep finally cloaked itself around her, like a thick mist that obscured all thought.

The days and weeks passed, and Lucía was kept busy with her studies until one day Don Fernando told Lucía that it was time to harvest grapes in the vineyard and asked if she would like to help pick them as her mother had done on many occasions. Lucía was excited and, as a surprise, was given her very own straw hat to protect her from the sun.

Yamina helped Lucía find suitable clothing to wear in the vineyard and found an old green undergarment and a matching green sleeveless surcoat to serve as an outer garment. Lucía put on her straw hat with the cord tight under her chin and walked down to the stable, where her father was waiting.

“Ah, are you ready, mi pequeño sol?”

“Sí, Papa,” said Lucía.

Don Fernando mounted his horse and, with one hand, lifted her onto the saddle. “Now you hold on to the horn tightly with both hands.”

“Sí, Papa. Can we go now?” inquired Lucía, who was very enthusiastic about the prospects of a new adventure.

Don Fernando held on to his daughter and the reins of the horse as they rode out of the palace gate, through the city, out into the countryside, down the long winding road, and to the vineyard below. Lucía noticed the peasant village across the road from the vineyard with its many white huts and the beautiful village church. In the middle of the village was the precious well of spring water from the mountains beyond.

Upon arrival at the vineyard, Lucía saw that it was indeed a busy place, with peasants who scurried about, picking grapes in the each of the rows. There were also several men who went up and down the rows with mule-driven carts and picked up the full woven baskets of grapes ready to be taken to the winery to be crushed into juice.

Before Don Fernando proceeded into the vineyard to help with the harvest, he decided to take advantage of Lucía’s eagerness to learn and show her around the complex. He realized that she was still quite young, but he felt this was a good time to introduce her to the family business and her future inheritance. He first took her to the winery, where wine was crushed into juice by a wine press and by peasant women who used their feet to crush the ripe grapes. Lucía was taken by the women who ran around in purple feet, and she wondered if the purple stain ever washed off. He then showed Lucía how the stems and other debris were filtered out and how the juice was stored in sealed wooden oak barrels for fermentation.

Finally, he took her to the cooper shed, where the oaken barrels were made. Once the wine in barrels was properly sealed, it was placed in the underground chamber by the winery for storage. Lucía was impressed by the dimensions of the underground chamber and the number of barrels contained inside it. Lucía was told that from the chamber, wine was delivered to all the inns, taverns, religious, and noble houses that were contracted. The remainder was for the palace.

Segoian wine making went back many centuries and had a superb reputation for quality and taste. Although Lucía seemed somewhat confused and bewildered by it all, Don Fernando reassured her that she would come to understand it all in time.

The vineyard was filled with peasants, who were engrossed in their work, and their assiduousness was seen not only in the woven baskets they filled but also in their sweat-laden faces. Lucía noticed that most of the workers were either wearing coifs or straw hats to protect them from the sun, and they wore their garments tucked into their belts so as not to interfere with their work.

Lucía was with her father when he spoke to the peasant leader of the village in charge of the vineyard. “Buenos días, Zito.”

“Buenos días to you as well, mi señor,” said Zito.

“This is my daughter, Doña Lucía, Zito.”

“Buenos días, mi señora. What a beautiful young daughter you have, Don Fernando. She is certainly worthy of a highborn rank.”

Lucía smiled with a slight bow of her head to acknowledge such a nice compliment.

“Gracias,” said Don Fernando, who beamed with pride.

While Don Fernando and Zito discussed the state of the vineyard, Lucía went over to a row to examine a cluster of grapes, pulled a grape off a cluster, wiped it off on her garment, and ate it.

“Did that taste sweet, Lucía?” asked Don Fernando, who surprised his daughter.

“Somewhat,” said Lucía.

“Good,” responded her father. “That is what we look for in checking whether grapes are ripe enough for picking.”

Don Fernando examined the grapes at hand and showed Lucía the color they should be when ripe, and then he gave one to Lucía and tasted one for himself. Lucía finished chewing on a grape but was curious as to whom Zito was.

“Papa?”

“Sí, mi pequeño sol,” said Don Fernando, who had bent down to examine another cluster of grapes.

“Who was that man you were speaking to?”

Don Fernando turned to his daughter and responded, “That was Zito, the peasant leader of the village.”

“What does he do?” asked Lucía, who was stuffing her face with another grape.

“His job is to maintain the vineyard and make sure the peasant workers are properly doing their job. He is responsible for the weeding, the grafting, and the picking of grapes, as well as the proper making and storing of the wine once it is made.”

“Why is the top of his head bald like Father Piña?”

“Because Zito was a former monk.”

“What is a monk, Papa?” asked Lucía.

“A monk lives in a monastery, gives his life to God, and helps the poor. They live in poverty and have very few possessions.”

Lucía bobbed her head and made a face that manifested understanding.

“Zito is very knowledgeable about the growing of grapes and the making of wine. I have deep respect for his judgment, which someday, perhaps, you will also have as well.”

“Papa?”

“Sí, Lucía,” answered Don Fernando, who was beginning to get annoyed at so many questions but felt it important to answer them.

“What does highborn mean? Was I born in the sky? I thought Mama was lying on a bed when I was born?” asked Lucía, who showed concern.

Don Fernando laughed. “Lucía, it is only an expression that means that you are of noble birth and destined for leadership someday as a condesa.”

Lucía nodded in understanding but made a face that indicated not completely. “Papa?”

Don Fernando interrupted her, “Lucía, why don’t you save your questions for later so we can concentrate on the matter at hand—the picking of grapes.”

Lucía agreed, and Don Fernando explained in detail the procedure of picking grapes by using a device called a pruning knife, which looked like a small scythe. He showed her how to cut the grape clusters and then put them in a woven basket next to him. Once the basket was filled, it was put at the head of the row, which was wide enough for a mule cart to come by to pick it up, and take it to the winery for crushing and to exchange it for an empty one.

Lucía was also introduced to several of the peasants who were working in the vineyard. They would curtsy or bow to Lucía and tell Don Fernando how absolutely beautiful she was and how much she resembled her mother, whom they all adored. Lucía was happy being compared to her mother.

After a while of helping her father pick grapes, she noticed several of the children who were her age playing across the road, rolling a cooper’s hoop with a stick down the hill. “Papa, may I play with the children across the road?”

“I see no reason why not. You have been quite helpful today putting the grape clusters in the basket. We’ll continue with this tomorrow,” said Don Fernando, who wiped his brow and stripped down to his untied white shirt.

“Gracias, Papa,” said Lucía, and she quickly ran off to join the group of children who were having races with their hoops.

“Lucía, make sure you remain in my view. Don’t wander off!” shouted Don Fernando.

“I won’t. I promise!” yelled Lucía on the run.

Don Fernando wanted Lucía to get to know the people of the village, and interacting with them was a good way of doing so. Yet he was very mindful of Queen Leonor always reminding him that Lucía was the granddaughter of a king and should not be allowed to take such liberties with peasants.

Don Fernando watched with a smile as Lucía fit in with the other children and, within a short time, was happily rolling a hoop down the hill with a stick, along with the other young peasants.

Don Fernando, as his father and grandfather once did, took pride in the hands-on approach in maintaining a vineyard, and he hoped to encourage Lucía to do the same.

As the weeks passed, Don Fernando each day would interrupt her studies and would show Lucía a different part of the operation to help reinforce her knowledge of the family business that one day she would inherit. Lucía also enjoyed her excursions with her father and, after a while, began to show some knowledge of what needed to be done. Such was the intellect of a bright young lady.

Lucía awakened before dawn and looked forward in going to the vineyard to help her father with the harvest. Most of the vineyard had been picked; only the last quarter remained. Lucía, with the help of Yamina and a couple of servants, got dressed, and then it was off to the chapel for morning prayers, after which downstairs to the great hall for breakfast. Lucía had a simple breakfast of toasted bread with honey, an orange, and her favorite, warm almond milk.

When Lucía arrived at the stables, her father was talking to Captain Gómez and overheard a small part of the conversation about a Moorish raid that had taken place at a small village ten miles to the south of Segoia. “Send out a couple of scouts to the south and see if they can locate the raiding party. Also notify the Grandmaster of the Order of the Christian Knights of Segoia to be prepared for any action that may arise. Be sure to send aid to the village. If you need me, I’ll be in the vineyard with Lucía.”

Captain Gómez nodded to Don Fernando, turned, and noticed Lucía, to whom he gave a polite bow of his head; he then went back to his room in the stable, where he spent little time due to his responsibilities.

Captain Gómez was the military commander of the army of Segoia. He was in charge of the one hundred soldiers who guarded the city and the palace, which also entailed training men on how to fight in battle in case the need arose, either by order of Don Fernando or the king.

Personality wise, Captain Gómez was always stern and disciplined and not much in the way of socializing; he did not marry, as he had little time for a family and found children to be an annoyance.

“Papa, why doesn’t Captain Gómez ever smile? And why is he always so grouchy?” asked Lucía to her father, who was getting ready to mount his horse.

Don Fernando smiled as he mounted his horse and reached down for Lucía.

“He has a lot on his mind. He has a big responsibility to protect not only us but also the rest of the condado.”

“Papa?” asked Lucía as they were riding out of the stable. “I have another question.”

“No doubt,” responded Don Fernando, who snickered.

“Does Captain García own any other garments beside that stinky mess of metal he is always wearing?”

Don Fernando let out with a roar of laughter. “That stinky mess of metal, Lucía, is called a suit of chain mail and is worn as protection in battle. I also have a suit.”

“But, Papa, you don’t wear it all the time as he does.”

“Remember, Lucía, he is a professional soldier, and he has to be prepared to fight at a moment’s notice.”

“Ah,” responded Lucía, who was satisfied with the answer, and then she fell silent for the rest of the ride to the vineyard.

Once at the vineyard, Don Fernando stopped at the winery with Lucía to check on the wine production. There he met Zito, who was examining the newly made oak wine barrels for leakage, and then they were off to the underground chamber, where the wine was stored and where Don Fernando took a count on the number of stored barrels.

Lucía noticed the darkness of the wine cellar if not for torches on the wall, which lit the way. The barrels were three high, and each barrel was carefully rolled in place. Each barrel was tapped with a spigot for tasting, as the wine was aged a month before delivery. Either Don Fernando or Zito would taste the wine to ensure quality of the barrel. When ready for delivery, a barrel would be marked with an x in charcoal. The barrels left over, and usually there were plenty, would be either for the use of the palace or used for gifts. Lucía was given a small sip from a couple of barrels and asked her opinion, under the guidance of her father, and was even allowed to mark several barrels with an x, which were taken out and placed in a horse-driven cart for delivery. Each shipment was accompanied by three soldiers to safeguard delivery and payment.

The sun was now only a few hours old in the sky, as Don Fernando rode around the remainder of the vineyard to inspect the grapes yet to be picked. Then he grabbed a basket and, with Lucía’s help, loaded it full with grapes. Lucía became a hit with the working peasants, as she politely engaged in conversation with the people she met in the field and sometimes played with the village children that she encountered. But today it was all business, for the last quarter of the vineyard had to be picked before the weather changed.

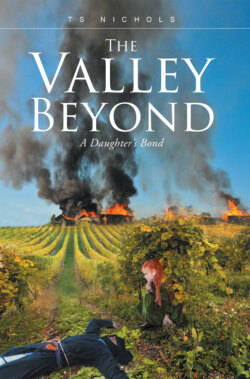

The vineyard was running with incessant energy when suddenly Don Fernando thought he heard screams and smelled smoke. He stood straight up and quickly ran out from the row where he had been working and saw about a mile away down the road in front of the vineyard what appeared to be a Moorish raid. His quick movements scared Lucía, who started to tremble in fear.

“Papa!” she yelled. “What’s happening?”

Don Fernando rushed back, quickly had Lucía lie on the ground, and covered her with all sorts of debris that he could find. “Lucía, I want you to stay here and not move or make a sound until I come back. Do you understand me?”

“Sí, Papa, but what is going on?” asked Lucía, who was visibly upset.

“It will be all right, I promise, but you must do as I tell you. Do you understand?”

Lucía nodded.

“That’s mi pequeño sol,” said Don Fernando, and he ran out to the road. To his horror, Don Fernando saw a raiding party of twelve Moorish soldiers, who wore black garments and black turbans wrapped around their necks and covered their faces. With only his white shirt, which was unlaced, a pair of green breeches, and a dagger, he ran toward the commotion. Suddenly, the village church bells rang and sounded the alarm. He could see from a distance that several huts were on fire and several peasants had been cut down and lay strewn across the landscape. Several women and children of the village had been kidnapped and hung over the saddles horns of their captors.

The small army in single file started to leave the premises and headed in Don Fernando’s direction, carrying their captives, but the enemy line maintained a good distance between each soldier. The first soldier came by swinging his scimitar. Don Fernando braced himself as he saw a soldier poised for the kill with eyes dark and foreboding. He quickly jumped on the back of his horse, pulled his dagger, and slit his throat. As he threw the dead soldier off this horse, he retrieved his scimitar.

The next soldier rode by, but a young girl who had been kidnapped was so busy trying to fight off her captor he couldn’t pull his scimitar. When he saw Don Fernando, he quickly dropped the girl, who ran off, and pulled his sword, but he quickly fell under the blow of Don Fernando’s scimitar. Two more arrived and fought Don Fernando on horseback, but they lost the fight with one losing another captive. The eight surviving soldiers rode off with several young women from the village.

A few minutes after the raid, Captain Gómez arrived with a contingent of twelve well-armed men ready for battle. Captain Gómez noticed Don Fernando still on the enemy horse and halted his contingent. “I see that you have been busy, Don Fernando,” said Gómez after he perused the bodies of the four dead soldiers, and found Don Fernando apparently unscathed. “Well, thanks be to God that you were not harmed.”

“You surprise me, Gómez. I never took you for a man of religion,” said Don Fernando with a smile.

“You know me, Don Fernando, always straight in the saddle.”

Don Fernando laughed at the comment and then became serious. “Eight escaped, carrying several women, and headed south on the Madrid road.”

“Most likely they are heading back to al-Andulus. Well, we’ll find them and bring back the women and whatever else they stole. Adiós, my friend.” With that parting comment, Captain Gómez led his contingent south toward the direction of the enemy.

“Good hunting as always, Gómez,” said Don Fernando as he hurried back for Lucía. “Lucía! Lucía!” cried Don Fernando.

“Over here, Papa!” cried Lucía, who stood up and wiped her garment off from the clinging debris of the ground.

“Are you okay, mi pequeño sol?” asked Don Fernando, holding onto her tightly.

“Sí, Papa, but I was very worried.”

“Well, it’s all right now.” After an embrace, Don Fernando started to walk down the road in front of the vineyard with Lucía. To his surprise, Yamina came riding on a horse. After having heard of the raid, she had hoped to find Lucía.

“You certainly came at the right time, Yamina. Take Lucía back to the palace and have her cleaned up. Avoid the village. It’s no place for her right now.”

“Of course, Don Fernando,” said Yamina.

Don Fernando bent down and told Lucía, “I want you to go back with Yamina. I will be back later.”

“Sí, Papa,” said Lucía. Don Fernando mounted her on Yamina’s saddle, and they both rode back to the palace.

As Yamina rode away with Lucía, Don Fernando traveled to the village to see the devastation. Smoke filled the air and masked the confusion that was taking place. The men of the village had formed a fire brigade with the help of several soldiers to put out the fires. A line extended from the well to the huts that were still ablaze. Another group of men were putting out the fire that had destroyed several rows of the vineyard. Peasants were milling about in confusion and disbelief. Father Piña was already praying over the bodies of the dead.

Zito met Don Fernando as soon as he dismounted.

“How many are dead, Zito?”

“Three here in the village and two more in the vineyard, where the men were cleaning up the debris from the harvest.”

Don Fernando stood in stunned silence. The attack had been a complete surprise. This had been the first raid as long as Don Fernando could remember.

Don Fernando turned to Zito after he had examined the area from the spot where he was standing. “I would have thought the Duero Valley to be safe from the Moors, but they seem to be growing bolder. But I never thought they would be so bold as to attack here.”

“There was no defense, Don Fernando. They struck in complete surprise from nowhere.”

“There is no such place as nowhere, Zito, and that was my first mistake. But I do wonder what happened to the scouts I sent out several days ago. They should have been back by now and could have warned us about a possible attack.”

Father Piña interrupted his conversation, “Don Fernando, it’s good to see you here. The village people are frightened and need reassurances from you. There are already five dead and several wounded.”

“I understand, Padre,” said Don Fernando, and he called one of the soldiers who had helped in the fire brigade.

“Mi señor,” responded the soldier.

“Go fetch my physician to help with the wounded.” With the order, the soldier mounted his horse and rode off quickly to Segoia.

After several hours, Don Fernando was able to access the final damage, and it wasn’t pleasant. Five huts had been burned to the ground and several more were damaged, six people had died from the attack, and three more were wounded but not severely. Three young women were missing, and three rows of the vineyard had been burned. Fortunately, the grapes had already been picked from those rows.

Don Fernando was able to assemble all the village occupants in the village church to reassure them that they were safe and that the possibility of the Moors returning was unlikely. He further promised he would get carpenters to rebuild the huts that were destroyed and arrangements would be made for the homeless to have lodging in the city. He would replant the rows of the vineyard that were burned and that Captain Gómez was currently seeking the missing girls. He also would send six well-armed soldiers to guard the village. The village people were pleased with Don Fernando’s assurances, which now allowed him to go back to the palace to see to his daughter.

The weeks passed, and Lucía was having nightmares about the events of that dreadful day. Unfortunately, while Lucía was hiding from the Moors during the attack, she had caught a glimpse of one of the saboteurs who had kidnapped a girl about her age and had held her tightly by his side. She was afraid that if he had lost his grip on her, she would have fallen and been trampled by his horse. She had also witnessed a soldier who had been struck down by her father fall to the ground not far from where she was hiding, with his eyes still open in death. Also, between the smell of the smoke, the noise, and confusion of the peasants, all drew images that she could not escape and were seared on her mind forever.

Don Fernando and Yamina tried to comfort Lucía as much as possible and told her that the kidnapped girls were all rescued and returned safe and all personal property stolen returned to its owners. The remaining Moors who had invaded the village would never hurt anyone again. These events were good news to Lucía, who had worried about the girls who were kidnapped.

The events of the past weeks had overshadowed the concerns that Yamina had concerning her future as Lucía’s tutor. She was getting on in age and did not feel up to teaching the advanced subject matter that Lucía was capable of learning, but she was willing to stay on for a short while as her nurse.

Don Fernando complimented her for her years of service in teaching Lucía basic subject matter and said that he would speak to the king about a future tutor for Lucía. She would be welcomed to stay on in the capacity of a nurse.

Within days, Don Fernando addressed this issue with the king and queen.

An idea was suggested that Lucía be tutored by Berenguela’s instructor at the royal palace. However, it was decided that it would be best that Lucía remain in Segoia. Therefore, a new tutor would have to be found, and only the best in Europe would be considered. The question remained where such a tutor could be found. Perhaps one could be found at the University of Paris or Bologna? It was decided that they would write to His Holiness, Pope Clement, for his ideas on this matter.

Meanwhile, it was Lucía’s birthday, and Don Fernando had a special surprise for his daughter. Lucía was told to meet her father in the stable. Lucía ran down to the stable, but when she arrived, there was no one in sight, not even José, the stable keeper.

“Papa, are you here?” asked Lucía, not sure what was happening.

“Over here, mi pequeño sol,” said Don Fernando.

Lucía followed her father’s voice around a stall. When she found him, he was in another stall with a beautiful white horse, along with José. “Happy birthday, Lucía,” said Don Fernando, who stepped back to let Lucía examine her birthday gift.

“This is my horse?” asked Lucía as she raised both of her hands to her face in an expression of amazement and disbelief.

“Sí, mi pequeño sol, and ride it in good health,” responded Don Fernando.

“Gracias, Papa.” Lucía went over and embraced her father with tears of joy.

“This is a two-year-old white Arabian stallion, purchased at great expense from a trusted horse dealer who was recommended by your Uncle Alfonso.” Lucía approached the horse, petted his face, and then embraced it wholeheartedly.

After a period of time, Don Fernando asked, “What are you going to name him?”

Having had the opportunity to examine him for several minutes, Lucía announced with a big smile, “I shall call him…” After a slight pause, she said, “Rodrigo after El Cid, Papa, from the stories Yamina told me about him and what a great hero he was to Castile.”

Fernando smiled. “I could not think of a more appropriate name. I’m sure that Don Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar would be more than pleased.” Lucía could now follow her father to the vineyard with her own steed.

While the days passed, Lucía had become accustomed to riding Rodrigo. Then news arrived that Isabella and her entourage were approaching Segoia. Lucía could hardly wait to see her friend again. So much had happened that Lucía could not wait to tell her stories, and yet what about Isabella? She had not heard from Isabella since the first letter sent to her some time ago.

Within a couple of hours, the day that Lucía had been waiting for finally arrived. She and her father awaited for the entourage to arrive on the palace grounds. Upon arrival, Lucía watched carefully as Don Alfonso Coronado stepped out of the wagon first and then helped Isabella out next. Lucía was waiting for Isabella’s mother to also disembark, but that was not the case.

After a pause, the two walked over to greet Don Fernando and Lucía. Lucía could tell something was horribly wrong, as Isabella had red eyes and tears were streaming down her face. Lucía escorted Isabella into the antechamber of the great hall, followed by her father and Don Alfonso Coronado. However, Isabella did not stay in the anteroom. She went immediately out to the garden and sat down on a bench in front of the fountain, where she could seek comfort, with Lucía in close pursuit.

Once both were seated next to each other and Isabella had time to quiet down, Lucía asked, “Why are you so sad, Isabella, and where is your mother?”

Isabella started to grieve again and choked back tears in an attempt to speak and be understood. “Mama is dead, Lucía,” cried Isabella as she wiped away her tears with a piece of linen.

“Dead! Did you say dead, Isabella?”

Isabella nodded. “Sí.”

“But how did she die?”

“Lucía, didn’t you receive the second letter I sent you?”

“No, I only received the first,” said Lucía as her eyes started to water.

“Well, we never left Coimbra. The day before we were to leave, Mama said that she felt ill and retired to the bedchamber. That night, a court physician came to examine her, bled her, and then administered some sort of herb concoction that she had a hard time drinking. I stayed next to her all night. The next morning, when I awoke, I noticed that Mama was even worse than the night before. Again, the court physician was called. After he examined her, he said that she was in God’s hands now. I’ll never forget how he said that.

“Shortly, after the physician left, Mama, who was very weak, whispered for me to come close to her. I rose from my chair and put my ear to her lips, and she again softly whispered to me. She told me not to be afraid, that death came to everyone, to be brave for Papa, and to always keep the faith. Then I saw her smile, after which she took her last breath.” Isabella could not hold back her tears any longer, but she continued on with her story, barely understood. “Lucía, I wept and wept for several days after her death until I had no tears left.”

“And then what happened, Isabella?” asked Lucía, who was also weeping.

“The family had a funeral. My uncle and Papa both agreed to have her buried next to my grandparents in the church crypt at the family estate outside of Coimbra.”

“How awful, Isabella. I am so sorry,” said Lucía, who wiped away her tears, and they both embraced.

That night, Lucía went to the palace chapel and said a special prayer for the kind and gentle person that Doña Teresa had been and the mother she had never known.