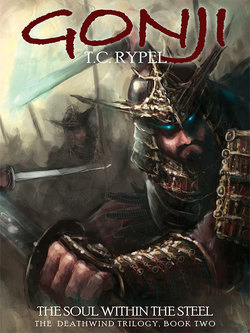

Читать книгу Gonji: The Soul Within the Steel - T. C. Rypel - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

Gonji Sabatake emerged from the tailor shop into the rain-slicked cobblestone lane, suppressing a grin of self-satisfaction. He was freshly scrubbed and shaven. His topknot was tied just so. And he sported the new sleeveless tunic and breeches he had recently commissioned, plus thick woolen socks for under his sandals to replace his worn tabi.

He adjusted his swords in his obi, the wide sash cinched about his waist, in such a way that they rode nearly horizontally, snug but comfortable as they always must be. He rubbed his stinging face pensively and glanced about in the humid morning air. The day would be hot and thick; murky clouds sagged from horizon to horizon. A good day for an indoor banquet.

He smiled and made off down the street, leading Tora by the reins the short distance to the tanner’s. His leather goods—the cuirass, pauldrons and vambraces, and riding boots he had ordered—were not ready; so he mounted and clopped off toward the marketplace at an easy gait. No hurry. Little to do this day until the banquet. But then—hah! A first-hand look at storied Castle Lenska! And at long last a meeting with the mystery king and his sorcerer.

This would be a day marked in memory; of that he was certain.

He had risen early to find Garth Gundersen already gone on some business at the foundry. Wilf had been pressed into service at the forge. Sullen and irritable, Gonji’s closest friend among the Gundersens was again brooding about the fate of his Genya at the castle; so the samurai had decided it was just as well to be free of his company this day. Strom, the shepherd son, and Lorenz, the Executor of the Exchequer, had been none too gracious in their invitation to breakfast. Gonji had eschewed it in favor of a short practice session in the hills.

Judging by the Gundersens’ mixed hospitality, he decided he’d best find lodgings elsewhere soon.

The marketplace was alive and healthy this misty morning, the moist air bearing the sundry sounds and scents of commerce. There was an aura of normality about Vedun, even the soldiers now unwittingly taking their place in the mundane order.

Gonji sated his empty belly with fish and ale, which he consumed languidly on a stone bench near the stalls. The bell tower sounded ten bells, and the shallower timbre of the chapel bell called some to a worship service.

A few of the people Gonji had met at Michael Benedetto’s house the night of the memorable boxing matches passed by and greeted him. Among these were Stefan Berenyi and Nikolai Nagy—he couldn’t recall which man was which, followed shortly by Monetto, the biller; and Gerhard, the hunter and fletcher, a longbow slung over his back. They carried between them a large sack of small game that evinced the latter’s prowess with the bow. Monetto steered them toward Gonji and began to make small talk, but they resumed their course to the stalls at Gerhard’s insistence. His concern over the freshness of the game precipitated the usual argument between them that could be heard long after they had departed.

Then Gonji thought he spotted a blonde head that might have belonged to Lydia Benedetto. He craned his neck to peer into the crowd, but from the spot he watched there emerged two Llorm footmen, who suspiciously returned his gaze. He rose then, his thoughts turning to military concerns...in a manner of speaking.

Let’s see what’s on their minds.

He took Tora by the reins and walked down an alley. Turning into the first intersection, he waited. The pack that followed him approached his vantage a minute later, whispering and muting their stealthy steps.

“Eeyah!” Gonji cried, leaping out at them, his scabbarded Sagami’s pommel pointing into their midst.

The children screamed as one and stumbled backward. Then they laughed with relief, and Eduardo, their leader, came forward, flashing a hand in greeting.

“All right, you scamps,” Gonji said sternly, “what do you want with me?”

A tiny girl clung to the back of Eduardo’s breeches, regarding Gonji with big terrified eyes as the boy spoke.

“We just wanted to see what you were getting into. My papa says that where you go trouble will follow. I didn’t want to miss anything.”

“So?” Gonji replied, affecting petulance. “And he was right, neh? Look what’s followed me.” He waved a hand over them, and they tittered.

“You look molto buono with your new clothes,” Eduardo said, appending a hand gesture that Gonji took to mean youthful approval.

“Arigato,” Gonji replied. “Now that I have your seal I can proceed with confidence.” He watched with raised eyebrows and folded arms as the boy walked around him appraisingly, the little girl traipsing behind like a shadow.

“Is that your sister?”

“No, that’s Tiva. She has no mother, and I get paid for watching her.”

“Do you do a good job?” Gonji bent toward the girl and spoke gently. “Does Eduardo watch out for you?”

The boys all laughed. “She doesn’t speak Italian,” someone said.

She was the most adorable child in Gonji’s recent memory and could scarcely have been more than four. When he reached down to lift her up, her large brown eyes seemed to engulf her face. She held a half-eaten roll in one sticky fist.

Eduardo translated what Gonji had asked.

“Nah!” she said in a tiny, piping voice. The boys laughed again.

“He doesn’t, eh?” Gonji said. “Well, we’ll see about that.”

“She says no to everything,” Eduardo explained.

Tiva offered Gonji a bite of the roll, and he pantomimed a full belly, but she persisted. He bowed and smiled, taking a small mouthful. “Domo, little blossom.”

He set her down. “You boys take care of her or—” He raised a threatening fist. “Now be off with you.”

“When are you going to teach me the sword? You promised,” Eduardo pleaded.

“I did no such thing,” Gonji said. “I said we’d have to take it up with your father sometime. What would a ragamuffin like you do with a sword anyway?”

“Kill the soldiers who killed Signor Koski,” Eduardo said matter-of-factly, bending to lace a shoe.

The simple poignancy of the statement stung Gonji. “Why would you do that?”

“Because Signora Koski’s been crying all the time since he died.”

Gonji worked his lower jaw thoughtfully, recalling the dead man, struck down by mercenaries on the day of the city’s occupation. “Doesn’t your father teach you that killing is evil?”

“Usually. But he’s not sure anymore.”

Gonji snapped his fingers. “Begone with you now. And watch out for the little one, hear?”

Eduardo bowed, too fast and too deeply, like a bird pecking at seed, and the other boys snickered. Gonji shook his head, corrected him, and sent them packing with a wink to Tiva, who waved her fingers.

He thought about the boy’s words as he watched them run down the lane. He’s not sure.... Indecision and lack of resolve would be a crippling problem if these people wound up in an armed revolt. Klann wouldn’t be shackled by Christian principles. He shook his head. Ah well, the mercenaries have backed off considerably since Ben-Draba was beaten to death by...hai.... He smiled thinly. Our other mystery man....

He leapt astride Tora and rode back into the main street, resolving to check in with Flavio.

Gonji was determined to treat his position as bodyguard to Council Elder Flavio with dignity and seriousness, although he knew that the hiring had been prompted by his own cajoling and Flavio’s desire to dispense the city’s debt to the samurai for having retrieved the body of Mark Benedetto. Yet bodyguard he was, and he would deport himself as a bodyguard. He had promised not to dog the Elder’s steps but had made a point of checking on his well-being from time to time.

He was clattering along easily toward the Ministry building on the Street of Hope when he was halted by the cry of a pedestrian on his left.

“Ho, there! A word with you, monsieur!” came the stentorian voice in ringing French.

Gonji pulled up and looked over. It was Alain Paille, the flamboyant and eccentric artist-poet whose revolutionary pronouncements since Klann’s arrival had caused the city no end of discomfiture and the occupying troops no little amusement. He was thin, dark, and willowy, with piercing blue eyes, a sketchy shadow of beard, and an unruly mane that no comb had furrowed in recent days. His paint-stained apron evidenced his current commission: an illustration in progress on the ceiling of Vedun’s chapel. In his hand he carried a furled paper.

“Behold the Liberator!” he shouted, wide-eyed, stopping in front of Tora. “He of whom ballades will be sung!”

Gonji glanced about self-consciously. Few had taken special notice of Paille, from whom such outbursts had long been expected. He was, as it happened, Vedun’s best-known tippler. Those who had heard now watched Gonji for a reaction.

Gonji cleared his throat. “Ja, well—what can I do for you?” He had ignored the French, spoke instead in High German.

“I’ve been seeking you. We must speak. I believe we share a dream. You do speak French, don’t you?”

“I speak French...of a sort,” Gonji replied. “But it gives me trouble. It’s a language I—” He groped for an appropriate word, came up with one.

“‘Disdain?’” Paille repeated with surprise. “But you mustn’t! All men of intellect and breeding speak French! I’ve been inquiring after you, and I believe you are such a man. Yours is simply a problem of pronunciation. But be at ease—we shall correct that. Do speak French, s’il vous plait.”

“I don’t please,” Gonji said with a wry look, “but I’ll speak it. What’s your business?”

“I think a drink is in order first. Shall we hie us to the auberge?” Paille pointed the paper toward the nearest inn, Wojcik’s Haven.

“Not now. I’ve business at the Ministry.”

“Wonderful! So have I,” Paille said, waving the handbill. “We can talk as we walk, oui?”

“Oui...wonderful,” Gonji said softly, glancing at passersby who were listening in on the conversation.

He dismounted and led Tora by the reins. He had been in a mood to ride alone, frankly hoping to encounter the swaggering Captain Julian Kel’Tekeli, to show him that Gonji was just as capable as he of affecting a display of cleanliness, polish, and poise. But now he stoically accepted the way karma had of laying low the proud....

“I am Alain Paille,” the artist boomed, “a painter, poet, and balladeer, chronicler of the times and tides of men, and soldier of freedom par excellence. And you are—no-no, don’t tell me—you are Gonji Sabatake, master of fighting arts from the fabled orient, dispossessed son of Japan’s mightiest warlord—”

Gonji winced and rubbed an itching eye, blew a long, impatient breath. Behind him, Tora nickered and bobbed his head.

“—champion of égalité and freedom, fated participant in the coming battle that will secure democracy from the strangling grip of monarchy and aristocracy—”

“Whoa, whoa,” Gonji groaned. They were tramping through a steep-walled lane, and Paille’s words echoed from one end to the other of its tunneling course. “Hold on, monsieur poète. Very sorry, but that’s a terribly mixed bag of facts and fancies. And listen, don’t you ever speak in anything but that blaring herald’s voice?”

Paille looked wounded. “Anger, pain, frustration, humiliation—these things are ne’er articulated by the calm and soft voice! But you are right, of course; we must be circumspect. The ears of the enemy are all about us.”

He leaned close and laid a finger across his lips with a conspiratorial suspiration, and Gonji caught a full blast of the artist’s midday pick-me-up. Wine. And a humble vintage.

“Oui, that’s best,” Gonji agreed, relieved. “Now...I’m not sure I understood all this—May we have continued in Spanish?” Gonji stumbled over the words.

“May we continue, not ‘May we have continued’,” Paille corrected. He sighed. “But, sí, Spanish then, the cutthroats’ language.... Such a shame. French is so elegant. My brother Guy, he always said that it sings to the ear, and Guy should know—he has only one ear, or still had the last I heard. But no matter—”

“Your brother Guy, who has only one ear...,” Gonji repeated blankly. But Paille had already launched into a summation of what he had said before.

Gonji shook his head. “Equality? Democracy? Peasants aren’t fit to rule themselves. There must always be a ruling class to guide them. And a soldiering class to preserve order.”

“Hmm. You’re allowing your politics and training to stand in the way of your destiny. But it is a fact, señor, that divine right of kings and governing power by virtue of birth to a privileged class are dying concepts. And it is a further truth that men are equals at birth and as such must be free to choose their own political order.”

Gonji kicked a stone out of his path. “Is that so? And who has discerned these ‘truths’?”

Paille looked surprised. “Why, I have, of course!”

Gonji smiled. “Ah, so you are another prophet, like this Tralayn?”

“Nooo! I am a visionary, not a soothsayer,” Paille qualified. “My vision is of an ideal, an earthly, temporal one. Not an ideal muddled by vague religious sentiment—oh! thank heaven my brother can’t hear me speak like this—”

“Your brother Guy, the one with only one ear—?”

“No-no, my brother David, the one who smiles like a nibbling rabbit—he’s a writer, an apologist of Holy Mother Church—”

Gonji looked confused. “Your brother David who—”

“No, I’m not a sleepy Christian like most who live here,” the artist continued. “They choose to cower in wait of a divine Deliverer and wouldn’t recognize one unless he came in a blinding light and on wings of a dove. I think they expect that the Christ has reserved His second coming for the plight of Vedun.”

“You don’t believe in Iasu, then—the Christ, the god of the West?” Gonji asked.

“Oh, He is there—somewhere, I suppose,” Paille replied. “He seems to play a hide-and-seek game with humanity, and currently it is His turn to hide. That’s why it is my duty as a visionary to shake these people out of their apathy and fatalism. But I fear my esprit and panache are misinterpreted. They believe me to be....” He shrugged.

“A madman,” Gonji finished.

Paille scowled. “The ugly lot of genius,” he snarled. “You understand the Christian doctrines? Those that would proscribe violence even when one’s way of life is threatened?”

“That, I have trouble understanding,” Gonji replied thoughtfully. “But I’ve traveled in the West a long time, and before that I was a student of Christian priests in Dai Nihon—in Japan. I have found that their beliefs are as reasonable as any other in explaining some of the horrors I’ve encountered...the supernatural things....”

“Hah! I’ve yet to encounter anything that can’t be explained by reason,” Paille asserted. “The natural employed perversely—illusion—the uneducated are easily baffled—these are the ways that—”

Gonji was shaking his head. “So sorry, señor, but I only partly agree. There are things in the world that confound moral explanation even as they demand it. I believe that nothing natural can be wrong—although like you I know that the natural can certainly be put to wrongful use. I feel no compulsion to explain the wonders and mysteries of nature, uh—” He rubbed his forehead, trying to remember something. Then he smiled, remembering, and translated the poem into Latin, in which language it best retained the beauty of the Japanese:

‘Unknown to me what dwelleth here:

Tears flow from my sense of unworthiness and gratitude’

“That best sums up my attitude toward the unknowable wonders of nature,” Gonji said.

“That’s quite lovely,” Paille observed. “Did you compose it?”

“No, I’m not that profound a poet. It’s ancient. My father taught it to me, and his father to him—”

“But—” Paille began.

“But,” Gonji interjected, stopping his disagreement short of utterance, “there are those things that demand explanation by their, um, un-nature.”

“Unnatural quality, you mean.”

“Hai, arigato—yes, thank you. What do you make of this flying dragon, the wyvern? What possible purpose could it serve in any natural order?”

“It exists,” Paille said, “and so we must conclude that it does serve some presently unknown function in the order of the cosmos. Or, quite probably, it is at least part illusion, or the product of natural power as yet harnessed only by the rare few adepts among us. There must be a natural explanation, else all rational order crumbles and there is chaos. Nothing of the sane and mundane in the world could be counted on, even as it has been for untold ages.”

Gonji pondered this. Illusion.... He thought of the fantastic events he had lived through. Of vampires and dragons and beasts of fable that had crossed his path these many years. Can I have imagined that these things were what they were? Have I been self-deluded, misinterpreting every frightful event, recasting every gnome as a giant in flawed memory, even as shadow casts the shapes of things as they are not?

Iye. No, I have seen truly. Even if it is only I who have seen the truth, whatever that truth might ultimately mean.

The thought vaguely pleased his sense of unfulfilled destiny.

Gonji laughed breathily and changed Tora’s reins to his other hand. “Excuse me, por favor, but...knowing alone what I know of the wyvern, I must say that to call him illusion is fully the most ridiculous thing I’ve heard all week.” Paille looked offended but said nothing. The samurai then recalled Lydia Benedetto’s similar reduction of the supernatural to the inexplicably natural. What a difference a change in speakers made.

They were nearing the Llorm garrison, and soldiers passing by sneered to see the familiar artist, some jeering openly at him.

“Now don’t be starting any trouble,” Gonji found himself advising in a curious reversal of his usual position. He halted Paille halfway through the delivery of an obscene gesture. “So you don’t believe in the existence of things that are purely of evil use, yet you ply your craft in churches—I’ve seen your work, by the way, and it’s very good.”

Paille brightened. “You think so? Merci, monsieur le samurai! But, oh, since these paintings of chapel ceilings became all the rage they’ve cost artists nothing but stiff necks and aching shoulders and arms. Then one must work under poor light and with inadequate equipment—Ah, but I see that I’ve slipped back into French again. Eh, may I continue?”

“Oui,” said Gonji patiently. “As Guy’s ear would have it.”

“Merci beaucoup. But I was saying that there are more portentous matters to concern myself with now than chapel ceilings. Oh, yes indeed, for here in this place, at this time, begins the struggle that will make men forever free of the yoke of monarchy. And you shall be the one to lead it.”

“Now wait a moment, Paille,” Gonji said, stopping and facing the Frenchman. Tora nudged his shoulder as he spoke. “Don’t be including me in any of your dreams. I’ve already explained how I feel about your...politicals—”

“Politics.”

“—whatever, and I make my own decisions about what I become involved in. Besides, this talk is madness, out here in the open like this. You’re every bit as crazy as they say.”

Paille’s eyes shone. “Oui, crazy enough to recognize destiny’s beckoning call, to see the coming jacquérie—the peasant revolution—that will begin in this insignificant place, among these humble mountains, and will echo down the corridors of time. And men will hail these days, for I shall record their moment, and they shall not be forgotten.”

Gonji rubbed the back of his neck, and a gurgling sound rumbled in his throat. They began walking again.

“You’ve taken up your predestined place already, you know,” Paille said in a quiet voice.

“How so?”

“Well, the fight at the square, for one. Quite an inspiration to the people. And now you’ve become Flavio’s bodyguard. A stranger, no? Bodyguard to the chief magistrate? And then I’ve heard other things...whispered.”

Gonji’s skin prickled. “Such as?”

Paille moved closer and said out of the corner of his mouth: “They’re saying you killed several bandits single-handedly while trying to rescue Michael’s brother. You’ve become the hero of the masses in a span of days.”

Gonji bridled. “Simply not true,” he lied. “Nonsense cooked up to produce just the effect it has. Those bandits were dead already when I arrived. And I’ll thank you to whisper that back to the whisperers next time, neh?”

He deeply regretted the prideful notion that had caused him to reveal how he had slain the boy’s killers. Damn that chirruping Strom Gundersen!

“Too late,” Paille said, grinning, “you’re already included in both my chronicle and in-progress epic! Epic poetry—that’s my current aesthetic passion. Ah, the glory of days past!”

“Don’t worry. I’ll have a look at it before long, and I’ll have my blades with me,” Gonji advised, tapping the hilt of his killing sword.

“Ah, but those swords of yours will figure prominently in the epic. Of that I’m confident. I wish I had my manuscripts with me—oh! I do have something, the work of a friend—” He fished inside his tunic and produced a crumpled parchment. “—arrived last week—all the way from England. You’re a man of intellect. You possess discerning critical faculties. Tell me what you think—”

“Well, I’m no great critic of poetry—”

“Just listen,” Paille ordered, holding a hand in front of Gonji’s face. “It’s a sonnet—tacky, sloppily sentimental form—mercifully dying out, I think, but it goes:

‘No longer mourn for me when I am dead

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Giving warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world, with vilest worms to—’

“What’s the matter?” Paille asked in annoyance, finally seeing Gonji’s head shaking.

“I don’t understand English,” Gonji said.

“Oh—well—let’s see—” Paille did a hasty translation of the sonnet into French, which Gonji strove to follow.

After a second reading, Gonji stroked his chin reflectively, then said, “Well...I think it’s quite good, although I’m sure the language suffers in the translation.” Paille made a small squeaking sound. “But is he saying that he should be forgotten when his present life has ended? No life should be forgotten.”

“No, of course not. This fellow should forget this sonnet business and apply himself to the stage. My brother tells me he’s quite an accomplished actor.”

“Your brother—Guy, with the one ear, or David, who smiles like a rabbit?”

“No-no, Gaston, the big strong one, who chose the stage against all advice.”

“Gaston,” Gonji repeated, rolling his eyeballs.

He recalled something he hadn’t thought of in years: his twelfth summer—the song of a lark—an indiscretion—the certainty of young death—

Gonji smiled. “Listen to this—

‘The soft white blossom—

Her eyes, markers of my grave.

My heart yearns for time

As shadows stretch and move:

The lark remembers my duty.’”

“That’s very interesting,” Paille declared. “What does it mean?”

“It is waka poetry,” Gonji replied proudly. “And that was my death poem—composed a bit prematurely, as it happens.”

As they neared the Ministry Paille questioned Gonji about his origin and background. The samurai spoke wistfully of Japan, of his father, the daimyo Sabatake Todohiro-no-Sadowara; of bushido and its seven basic principles: justice, courage, benevolence, politeness, veracity, honor and loyalty; of the samurai’s profound sense of duty; of Gonji’s repudiated heritage—but not the details of the duel over star-crossed love fought with his rival half-brother....

“This code of bushido is marvelously clean and simple,” Paille said. “But it can never be espoused here in eclectic Europe. Oh, no indeed. I’m afraid you’ll have to exempt yourself from its precepts here if you’re to retain your sanity. And as for duty—” he chortled “—as I’ve said, you’ve found it. You’re destined to be the great warrior-liberator who will help end monarchic tyranny. Your Western half has caused you to come here seeking fulfillment of that destiny.”

“No, monsieur wild-eyed poet, I’ve not come to find death in a radical social...upheaval—”

“Oh, good word, oui, your French is improving already—”

“—but,” Gonji continued, drowning him out, “but to seek a thing of legend called the Deathwind.” He explained the quest he had been set by a dying Shinto priest.

“Mmm,” Paille mused. “The Deathwind....”

“You’ve heard the legend?”

“Indeed, I know it well. Look about you. The Deathwind is our ever-present companion, the whispering breeze that serenades us when we’re alone in the dead of night, reminding us of our helpless, teeth-gnashing mortality.” Paille ended with a great theatrical flourish and flutter.

Gonji sighed. “What I need is a concrete explanation, something I can touch. Not more of your airy poetry.”

“If you have to ask what the Deathwind is, then perhaps you’ll never know—oooh!” Paille felt his tender jaw, which yet bore the bruise of Gonji’s punch on the night of the wyvern battle, when the fleeing samurai had tripped over the drunken artist.

“What happened there?” Gonji asked in amusement.

“Oh, the brigands jumped me the other night. Must have been three or four of them, but I escaped with only this souvenir.”

Gonji suppressed a laugh. “So you’re a fighting poet, then?”

“My purpose is to inspire others in the fight for freedom, but when the occasion warrants I can take care of myself.” He looked about cautiously. Then he produced a dagger from inside his tunic, winking at Gonji.

They stopped before the Ministry of Government and Finance, an imposing stone edifice with huge granite columns guarding its portals, which housed the Chancellery of the Exchequer and sundry bureaucratic offices. Children played on the steps without, waiting for parents on business. The Ministry was the nexus of commerce in Vedun, a short distance from the square and the bell tower and chapel, whose twin peaks fingered the steely sky. A large banner bearing Klann’s coat-of-arms now hung limply against the Ministry’s facade.

Gonji wondered at the curious appointments: the beast of fable and seven interlocked circles, two of which were blackened out. And as if the thought had spurred him, Paille began to blazon the crest aloud:

“Per bend sinister, Azure and Argent; in dexter, a basilisk (or something still less wholesome, perhaps) rampant-regardant, Or; in sinister, seven interlocked circles, two of the same Purpure; motto...incomprehensible.”

“You can blazon such devices, eh?” Gonji said, eyes sparkling with interest. He remembered the other coat-of-arms he had seen several days past. “Listen, Paille, do you know another from these parts, a green-and-red field, with a gold cross at the bottom—”

“Indeed I do,” the poet answered with arched eyebrows, “as do all in these environs. Of late it hung here in this very spot. The Rorka crest....” He set one foot on a hitching rail and puffed up his chest, then with eyes closed recited rapidly: “Per fess engrailed, Verd and Gules; in chief a lion, Argent, passant-guardant; in base a cross, Or (a hideously garish coloration, that); motto: ‘In Vita Sicut in Morte’—‘In Life as in Death.’ That is, presumably, at the breast of the Lord. ‘In Life as in Death’ indeed...,” Paille scowled.

Gonji shook his head sadly, for he had been sure it would be so: It was a patrol of Baron Rorka’s troops he had helped slay while in the employ of Klann’s 3rd Free Company.

“What do you suppose those blacked out, or purpled out, circles mean on the Klann crest?”

“Hard to say,” Paille replied. “Purpure is the royal hue, so it doubtless represents Klann. But two of the seven filled, the others not...?” He shrugged and turned his palms up.

A little boy brushed past them as Gonji tethered Tora, another child following quickly in yelping pursuit.

“The enfants perdus,” Paille muttered, watching them.

“Eh?”

“The children of forlorn hope,” the artist explained. “These are the ones who are trampled under the hooves of royal ambitions. They look to you for deliverance, monsieur le samurai—will you fail them?”

Gonji frowned, but deep within he was warmed by the pride born of the champion’s mantle. His nickname swam on the eddies of his thoughts, that name he had earned farther west.

“Listen, Paille, you’re knowledgeable on lore and legend. Ever hear of the Red Blade from the East?”

“Mmm. Let me think...oui, I do know it. It speaks of a fabled warrior—a cossack, I think—who carries a saber of ruddy metal. Never bested in battle. Some say the blade is colored by the many—what’s wrong?”

“Forget it.” Gonji’s brow furrowed as he mounted the steps to the Ministry, resolving to carefully consider anything the glib Frenchman told him in the future before lending it any credence.

Paille stared after him a moment, wondering what he had said to alter the oriental’s mood. They were certainly a touchy lot. He shrugged and loped up the steps after him.

* * * *

Phlegor, the craft leader, signed the last bill of lading acknowledging receipt of the guild’s materials.

“You’re sure it’s all there?”

“Quite sure, Phlegor,” Lorenz Gundersen said with weary indulgence.

“You remember what happened last time the Jew brought the Viennese order.”

“And you were credited and sent a premium when the shipment was corrected,” Lorenz replied without looking up from the sheafs that now occupied his attention. He dearly hoped the discourtesy would send the feisty guildsman packing.

The Ministry was at the peak business hour. Stools and tables were twisted askew in the lobby. Voices chattered incessantly. Stale food and beverage smells clung in the informal air of the heavy late summer caravan trade season. Overworked secretaries argued with traveling chapmen and locals alike in small booths lining the walls. Flavio, the august Council Elder and his snowy-bearded adviser, Milorad Vargo, could be seen huddled over a desk through the doorway of a rear chamber. Boris Kamarovsky, the ferretlike woodworker, leaned against a foyer window, gazing about him dimly as he waited for his boss to finish signing for the recent trade goods shipment. It was humid after the recent rains, and the atmosphere lent itself well to an epidemic outbreak of irritability and headaches.

Phlegor seemed to thrive on such tense circumstances.

“Listen, Lorenz,” Phlegor said, leaning forward over the counter, “is that Jap still staying with you Gundersens?”

“Ja, for now,” Lorenz responded casually, applying the Seal of the Exchequer to a pile of documents.

“I don’t like the way he swaggers around here like he’s master of the city.”

Lorenz cocked an eyebrow. “Oh? I understand you were quite taken with him the night of that ridiculous brawl on the rostrum.”

“That was then. Sure, it was amusing to see Klann’s bandits take their licks. And he showed he could fight, even if it was only with his feet, like some damned fighting cock. But what’s he done since then, except strut around town eyeing up the women? You people haven’t mentioned the council meeting to him, have you?”

Lorenz stopped in his work. His lips perked, and he eyed the craftsman sidelong. “I’ll just pretend you never said that.”

“Hey, no offense! I just don’t trust strangers, that’s all. Especially heathens and infidels.”

“That’s your privilege.”

“I understand Flavio’s taken him on as a bodyguard,” Phlegor said loud enough to turn nearby heads from their business.

“That’s his privilege,” Lorenz said at length.

“Pretty rash, if you ask me.”

Lorenz bit his tongue. Then he said, “Weren’t you in favor of the hiring?”

Phlegor thought a moment. “Ja, I suppose...but that was the other night. I’ve had time to think about it since. Is he really going along to the castle banquet?”

“So I understand.”

Phlegor shook his head. He leaned close again. “What about that wildman who killed the big soldier and then jumped over the wall? Anyone know who he was yet? God, that was something!” Phlegor breathed an awe.

The Executor of the Exchequer exhaled deeply and flung down the Seal. Leaning back in his chair, he smoothed the wrinkles out of his doublet and peered up at the insistent craft leader.

“No, Phlegor, no one knows. But I’m sure you’ll be the first to find out, and then you can tell us all.” Lorenz’s voice reeked of the haughty sarcasm that was his trademark.

“Well ten-to-one he’s a friend of the monkey-man, and I’d like to know what they’re planning. As far as I’m concerned they’re just two more invaders trying to make a reputation at Vedun’s expense.”

Boris snapped to attention at the window. “Phlegor—here he comes now!”

“The Jap?”

“Da.” Boris smirked. “Still got his hair tied up on top of his head like a turnip. And guess who’s with him?”

“Who?”

“That crazy Paille!”

“Oh, Jesu Christi!”

Lorenz’s face dropped into a cupped hand, the elbow resting on the chair arm. “Oh no,” he grated in a low voice.

When Gonji entered the foyer and bowed to those in the lobby, Boris scrambled over to stand next to Phlegor without a look in the samurai’s direction. Several people returned Gonji’s bow nervously, the babble of voices diminishing to sporadic whispers.

Gonji spotted Flavio in the rear chamber, and the Elder waved him over. He removed his sashed swords with a slow, elegant motion and carried them, sheathed, in his right hand to Flavio’s office.

Then came Paille.

“Gundersen! My paints! Did they arrive with Neriah’s caravan?” The artist waved his order form over his head.

Lorenz gathered himself to fend the coming storm. “Not this time, Paille. Can’t you just begin on another section with the colors you still have—?”

Then the storm broke in all its aesthetic fury.