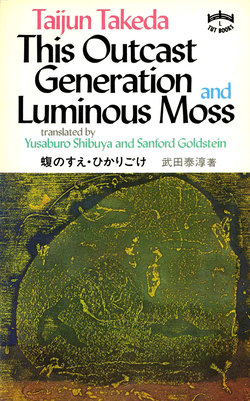

Читать книгу This Outcast Generation and Luminous Moss - Taijun Takeda - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHIS OUTCAST GENERATION

I

—PERHAPS it's easier to go on living than you think.

I had laid my pillow on the concrete platform used for drying laundry, and I was relaxing in the sun. I took a sunbath there every morning after coming out of my dim back room. In the corner, as usual, were two chickens pecking away at leftover rice and withered vegetables. From the alley below came the almost threatening voices of Chinese haggling over bargains from the Japanese. The voices of the Japanese were low, feeble, and confused, so their customers sounded even more overbearing in their abuse. Only the voices of Japanese children at play were full of energy and happiness. Oddly enough, those joyful cries made the parents even more irritable.

—Since everyone's apparently able to get along like this.

With my weak vision it looked to me as if the wall of a theatre beyond the house roofs stood out garishly white. It seemed to float radiantly white out of the blue winter sky.

—You can lose a war, see your country collapse. And still you can go on living.

Before I had realized it, the shop windows of even the Japanese were decorated with flags of Nationalist China and photographs of Chiang Kai-shek and his wife. I too had bought a small photograph from an old man peddling pictures of the couple. The snapshot had sold like hotcakes.

—All you need is a guardian angel.

To prepare for the inspection tours of the Chinese police, I had put the photograph between the pages of a notebook. When the Chinese national anthem was sung at the movies, the audience stood up and so did I, my eyes obediently on the flag and a framed picture of Sun Yat-sen, I had stood up apathetically, like a puppet, and then sat down, and the movie over, I had gone out through the crowds of Chinese teenagers pushing me around. I had merely listened indifferently as the agitated audience cried out simultaneously over a violently anti-Japanese film. Sometimes I had no expression on my face, sometimes I smiled reluctantly. Whatever the occasion, the only thing I really marveled at was my own ability to somehow continue living when I so easily might have been dead. At first, I believed that bearing the humiliation kept me going. But when I thought over the defeat and its aftermath, I felt no shame, nothing in fact. My blank face and reluctant smile were merely the mask by which-1 was simply living without any humiliation whatsoever.

I started to earn my keep by writing out documents in Chinese. There was no end of callers. Since my landlord was a broker, his customers of the past fifteen years came to me in a constant stream. They were so totally confused that they even talked respectfully to me! Even in defeat life marches on. As if to confirm this principle, clients came to me to lodge complaints of various kinds. A pale old man once asked me to help him after his employer had been robbed and kidnapped. Unless the police were notified immediately, his boss would be in for some real trouble. So urged, I had gone into my dark back room on the second floor. Even in broad daylight I turned on the electricity. I spread out my carbons on a tangerine crate. I sluggishly went about my task with the help of a Japanese-Chinese dictionary. And the job finished, I was paid off. I would hesitate in giving my fee. The currency of the puppet-government was still in circulation, and I had to figure out the price of four packs of cigarettes. The money I earned came out of human misery. Beautiful reflection that! It's a pity the thought lasted only two or three days after I had gone into my trade. I wanted my sake and rich food so that trouble and customers were an absolute prerequisite.

Someone would be evicted tomorrow. In one way or another, someone would have to move his belongings into the Japanese compound. A Japanese man desired Chinese citizenship in order to return to his family in Taiwan. A Japanese drafted to dive for salvage wanted to give written notice of illness—that was how eager he was to get home. Some Japanese wished to illegally convert the goods they had on hand into money, others to open street stalls. A Korean-born reporter came. A blind person came. A pregnant woman came. A Japanese merchant who promised to pay me anything I asked and a sick man hardly able to walk because of malnutrition, they came too. I undertook anything. I prepared documents audaciously. I wrote irresponsibly. All I cared about was getting my documents approved. Sometimes I chose expressions designed to move the heartstrings of officials in charge of us Japanese living in China. Sometimes I developed watertight arguments. I wrote grandiloquently. I wrote half-truths that favored my clients. I finally reached the point of writing barefaced lies. At the very least, however, what I did write was understood. That was why most of my documents got through. My customers came to offer their thanks. Before I realized it, I was gaining their confidence. Not only was I a popular transcriber. I began to be looked upon as a reliable guy!

My only thought was to get paid. I never felt I was working for the benefit of Japanese residents. Those that depended on me in this way I pitied. I found the world ridiculous in which a person as irresponsible, as incompetent as I, could still be useful. The world was too flimsy, too dissatisfying. Formerly, before coming to Shanghai and even later, I had studied hard, worked hard, thought hard. At that time not a soul had trusted me. After the end of the war I didn't study, didn't work, didn't think. But in people's eyes I was changing into a man of integrity, at least to the extent that I had never before been considered for the role. No longer did I have any ideals, any faith. I was merely breathing, and that, apparently, was what people expected of me. I fell into the habit of looking sober as a judge. No matter what the proposition, I wasn't surprised. That was the kind of person my customers were seeking advice from about their personal affairs. A man married to a Chinese woman wanted to know if he ought to get a divorce or not. A Japanese wife about to run off to her sweetheart just before her repatriation told me her scheme. Occasionally, therefore, I reached the position of the Catholic priest who lends an ear to confessions and vows.

One morning I was drinking some sake left over from the night before. I gulped down a cup. Though the wine was beginning to sour a little, I was in a hurry to get drunk. Then I intended to write a poem I had called "The Man Shot to Death." The execution of a German war criminal I had seen in a newsreel had made quite an impression on me... Shots. Inside the white smoke the upper part of the bound body jerked forward. With that it was over. It had really been simple. As plain as day. So truthful as to be intensely satisfying. In it was something beyond logic. It had pleased me immensely.

Upper torso in a forward fall—

Why?

Gravity's law.

As I was jotting down these expressions in bold strokes, my landlady called up to me that I had a visitor, a young lady who had come a few days before.

I put a padded robe over my wrinkled workclothes and went down. Young? Probably her, I said to myself, remembering one of my clients.

Her husband was an invalid, but the real estate company that owned their house had demanded they vacate in three days. There wasn't a thing she could do by herself, so she had asked me to write a petition to the authorities.

My visitors always waited inside the front door. The sunlight through the seven or eight sheets of glazed glass in the roof made the doorway brighter than my room. When I had first seen that woman in winter clothing standing in the pale light, a shudder had gone through me. What had impressed me was her tall, slim body, her white face, like some flower at evening, her attitude, shy in a lovely sort of way yet seductively coquettish. I had felt as if something I had forgotten over a long period of time had suddenly turned up, a fantasy I had once believed in when I hadn't lost my aim in life.

"I'll do it."

In an efficient businesslike way, I had learned the essentials from her and had gone upstairs and composed a beautiful piece of prose. I had handed her the document I was so proud of, and without smiling, I deliberately demanded twice my usual fee. My business was the writing of documents, and I had long ago become contemptuous of romantic sentimentality. I had given up any feelings of anxiety about matters not related to my trade.

"Is that enough?" she had said, taking some bills out of her patent leather bag and putting them down on the mats. "It's probably been very hard on you since you started doing this kind of work," she had said, her eyes large and friendly as she looked up at me standing there.

"I've often read your poems. My husband likes them too. He's always asking about you." It had seemed to me she was reminiscing.

"What's that?" I had said, embarrassed, as if the flow of blood in my body had suddenly reversed itself. Why, just as I was about to receive my fee, had she started talking about my earlier poems, those terrible sentimental pieces?

—Always asking about me, did she say? Listen to that! "Take this to the Board and have them sign it," I had said roughly, gathering up the money.

She had thanked me, and when her beautiful legs were no longer in view beyond the dark door, I had tramped up the narrow staircase. I was so excited I felt dizzy. I had even bruised my right ankle as I missed a step.

Luckily I was drunk when she came again. After all, wasn't she a young wife, and even after the war, with plenty of money, was she really in need of anything?

"Well?" I asked rudely. "Did it get through?"

"Thanks to you, they made an immediate inquiry. We don't have to leave."

Her red and white checked sweater caused her white face to look even more dazzling. "Someone gave these to me," she said, holding out a pack of imported cigarettes. There was no sign she intended to return.

"Are you free now? I'd like to talk something over with you."

"Well? What is it?"

"It's difficult to talk here."

"In my room then?"

I took the cigarettes, worth several times my fee, and went upstairs. What a beautiful, graceful animal she seemed as she sat near me in my small dark room with its walls barren except for an electric light and a gas meter. Instantly my wretched back room was filled with scent and warmth, with something like the radiance of women. I spread out a dirty blanket and had her sit at the same time I did. Again I poured some wine into my cup from the half-gallon bottle.

"You men are lucky you're able to drink. You can forget everything."

I felt oppressed each time she moved her lovely legs in their silk stockings. I swore at myself, resisting, getting malicious even.

"We go on living, putting up with the humiliation. We're miserable. It's almost impossible to talk about."

"You don't say," I said with deliberate sarcasm.

"All we have is pain and humiliation." Suddenly her expression changed. She looked down, crying, her shoulders shaking. It annoyed me, yet I found her weeping charming enough. She was so gentle, so luscious, I couldn't help feeling sympathetic. Still, I wasn't going to let it get the better of me. She wasn't the only one that wanted to cry. If I could have, I might have tried a tear or two myself.

Yet her last remark, confirmed by her tears, had certainly turned out to be painful and humiliating for me too. I was drunk, but the pain I felt in her words refused to go away. I might reject them, ignore them, but I did feel their significance.

"I guess you know about Karajima. He was my husband's employer. What do you think of him, Mr. Sugi?"

Of course I knew how influential Karajima had been as a propagandist for the Japanese army. I had even seen him once, a handsome, well-built, fair-complected man. He was quite adept in his role as hero and gentleman. He wore tasteful ties, the best of clothes. In spite of myself, I could still accept his absolute self-confidence in treating others as subhuman. But I detested the way he played the sophisticate that knows every thought and emotion of the man he's with. It was stupid and depressing to be governed by such men of power. I had listened to his ranting voice and polished speeches, and even after spitting, I had been left with an aftertaste of something dirty. But when the war ended, I had forgotten him. I had forgotten his nastiness too. Once you started talking about nastiness, everything, yourself included, seemed nasty.

Her husband had worked in Karajima's printing division and later had been sent to Hankow. She had to remain alone in Shanghai. Karajima had offered to find her a room, and on the day they were to inspect it, she had gone to Karajima's office. When he had closed the door after her, he told her he had liked her from the first and violently threw his arms around her.

"Some of his workers ought to have been in the next room. I struggled and cried out, but no one came."

Though she might have been upset, she easily told me everything. Sometimes she stole a glance at me with those beautiful eyes of hers. Apparently she wanted to see if I was disturbed. I didn't let on that I was.

"He was like an animal," she said. Her words and look seemed to point an accusing finger at all men. I began thinking that if I had the power, I too—I even imagined that I was the one, not Karajima, who had those arms around her. What it had amounted to, at any rate, was that she had let him have her. She had lived on without even a thought of suicide.

"He had me every night after that." I kept staring at her body, and that searing pain I so patiently endured was possibly not unpleasant.

Out went a Karajima directive to Hankow, so her husband was stationed there until the end of the war. For the duration she had been Karajima's possession. Try as she might to hide from him, up he drove in his car. All the neighbors and her husband's friends knew about it, but no one stopped Karajima. When her husband had finally returned to Shanghai, he was totally emaciated from a terrible case of diarrhea. He was bedridden from the moment they had carried him off the truck. She was still kept by Karajima. He was generous with money and supplies. And sometimes he summoned her from the bedside of her stricken husband.

Her husband knew about their relationship and kept abusing her with it.

She admitted the affair and asked him to forgive her. He refused to take the medicine purchased with Karajima's money, but without these funds they wouldn't have been able to afford electricity, water, even the sheets the invalid was lying on. He was tormented by the thought that his friends had so contemptuously forsaken him. It was even more painful to have her consoling him. He often kept telling her how detestable she was, yet he said she deserved pity.

"He's good. And so like a child."

She rolled her tear-drenched handkerchief into a ball, and opening her compact, she began putting on some make-up. She colored her slightly opened lips a fresh red, and as she powdered her face, her cheeks kept expanding and contracting. She was skillful, thorough.

"Well, how about now? Karajima I mean."

"I've definitely left him. I'm determined to hate him until I die. He'll be caught soon since he's a war criminal."

A cold, blunt expression was on her face. When she finished speaking, I picked up my cup. I felt my grim smile had somehow distorted my face. I couldn't explain why I felt only suspicious then.

Did she really despise Karajima? Wasn't there more pleasure than misfortune in having given herself to him? Her resolutions to the contrary, she had, however half-heartedly, kept up the relationship so that some desire other than monetary might have been behind it. In her eagerness to live comfortably, or if not that at least adequately, I doubted if there was any self-accusation or humiliation behind the affair.

I imagined she had the same detestable human instinct to survive by merely living, by forgetting all about pain and humiliation, especially when I was so well aware of that same instinct in me. The simple assault of her charm made me feel even more convinced of the truth of my observation. I felt sick, depressed.

"I believe in you. That's why I've gone into all of this."

She poured me some wine.

"But I really came on my husband's orders. He doesn't want to see any of his former friends. He's read your poems and believes in you. He wants to talk to you. Can you come just once as a favor to him? He'll be overjoyed. We're so miserable all the time! How about tomorrow? It's best to come early. The past few days he's been quite ill."

She had returned after making me promise to visit the next day. At the same time I was worrying about the dust blowing all over the concrete platform I was lying on, the particles sticking to my skin, which hadn't been exposed to a bath for a month, I kept wondering if I ought to go. It made little difference if I did or not. Of course, there was plenty to interest me. Yet whether I went or not didn't really matter. There wasn't a soul to accuse me of not doing something to help them out of their situation.

As I walked along, a youngster selling candy kept pestering me. I find these kids annoying except when I'm drunk. At a street corner I saw a Japanese having his hat stolen by a young delinquent. That troubled, weak-looking face should have evoked some sympathy in me, but all the same I couldn't help finding it disagreeable. He had run a few steps after the thief and had stopped, relinquishing his hat, stealing a glance at me. I couldn't help feeling disgusted by the sight of his helpless eyes.

I reached the woman's apartment, the Indian gate-keeper opening the iron gate for me. He looked sharply at my Japanese-resident armband. I rang the doorbell three doors beyond.

She seemed quite delighted as she ran down the stairs. It made me feel good to have caused that happiness in her. But I sensed the contradiction. She was too lively, quite out of keeping with the daily depression she had talked about.

As I took off my shoes at the threshold of the third floor apartment, I saw the signs of a sick person in the next room. He must have been lying in bed waiting for me. I felt the tension with which he must have waited. Perhaps it was a momentous interview for him. To me it shouldn't have meant a thing. I would have been disgusted with myself had I made it momentous when it was nothing of the sort.

She offered me a cushion to sit on, a colorful one.

The invalid was so very thin that the flatness of his covers made it seem as if his body wasn't under them. At first he turned sideways to look at me, but he glanced back up at the ceiling right away. At that very moment heavy wrinkles, like a monkey's or a baby's just after its birth, formed on his face. He was crying. It was embarrassing to see his neck and shoulders shaking as he tried to stop himself. His forehead and cheeks were an ugly red.

The tears made it difficult for him to speak. His voice often grew weak, gave out.

"At first he had only diarrhea, but then a bad case of pleurisy set in. The fluid's been accumulating, so his heart is slightly out of place."

Her own voice was clear and crisp as she handed her husband a handkerchief and forced him to take some water. I was surprised by the speed and energy of each of her actions. How conspicuously youthful the color of her arms, the roundness of her calves!

"I have no friends to confide in, so I thought... you... you would do me the favor of listening. It's... such a humiliating story... So humiliating I can't tell it to just anyone."

I forced myself to look at his face, which was too weak and dried up to convey the violence of his emotions. It wasn't a pretty sight, yet I was reminded of my own good health. It caused me to feel self-confident, even superior.

"I'm no saint. And I'm not a person you tell secrets to. But I thought I'd better come up to see you. It was rude of me just to drop in," I said.

"I... I don't expect you to do... anything in particular for me. I just wanted to talk to someone like you. It's unbearable to be lonely," he said.

He looked much younger than me. He had been good-looking. Those clear, nervous, agitated eyes seemed to be anticipating my thoughts way ahead of time. The slightest change in my face caused a shadow of fright to skirt across his eyes. For a fraction of a second a bright trace of insanity was glittering in that shadow.

"Lately my wife keeps saying she wants to die. Not me. I've... things I want to do."

"You have? I envy you. There's not a single thing I care to do."

"You're wrong. You don't realize... you're doing something already. I will too. I'll do... what I couldn't do during the war. I must do it! I've been totally useless... up to now. This time at least... I'll do what I want! I'll get strong! I'll do something... to destroy men like Karajima! If I can't... then I'm going to be a thousand times more evil than he is!"

The feverish and excited invalid had been overexerting himself by speaking. I knew he'd die soon. It was strongly foreshadowed by his yellow skin, by the bridge of his thin nose. It was obvious he'd never achieve any of his goals. I felt no pity, only oppression.

"I've no contact with anyone... any longer. They all... hate me. She's cheated on me, and... I'm living off the money she gets from him. It's not right... to let this pass! It's terrible... to be buried with such shame. Without wiping out even a small portion of it!"

Her husband's remarks about her made her glance at me, her beautiful eyebrows shaped into a frown.

"It's terrible... to be hated," he said, stopping momentarily to regulate his breathing. Then he recounted the dream he had the night before.

He had become a leper. The offensive odor given off by his mouth and body made him unbearable to his wife. Seeing her frightened face fill with hatred, he felt he was losing his mind. She ran away and he pursued her, catching her, holding her tight, that terrible odor coming out of his mouth and from his body so that he had finally become aware of his own stench. She spat at him, cursing him, then fled. His loneliness had made him cry out.

"When I woke up and found I'd only been dreaming, I felt I was lucky not to have leprosy. I really felt relieved my sickness was just ordinary."

"That's all you dream about, isn't it?" she said. She looked tense as she prepared our tea. She was trying to smile but couldn't.

"My dream's about Karajima. I murder him in my dream."

She spoke casually, but her words sounded theatrical, melodramatic. They had the false ring of something feminine. Her husband's eyes became even more dismal.

"Mr. Sugi!" he suddenly cried out in a high thin voice. "I can't believe her! While Karajima's alive, I can't believe anything she says!"

Again he began crying. This time he didn't try to stifle it, crying openly, strange sounds in his throat mixed in with his words.

"You shouldn't talk like that in front of Mr. Sugi! It's too cruel! It's too much!"

"You keep on lying, that's why!"

"No matter what I say, you take it as a lie! I can't go on living like that!"

"You're living, aren't you? Aren't you living without a care in the world?"

His crying, staccato-like voice was a sick man's. But her tearful voice, even as she tried to suppress it, was bursting with the vigor of youth. Those two sobbing voices continued, sometimes intermingling, sometimes separating.

I took out one of the imported cigarettes I had received the day before. I had no matches, and she quickly pulled out a box of foreign-make from her pocket. She smiled, embarrassed by the tears on her cheeks.

"Oh, your tea's cold! Well, I'll serve you a nice lunch!"

I begged off since I wasn't feeling well. "It's my stomach."

"You're not going home!"

Her husband stopped crying, his expression changed, I imagined, since he thought I was about to leave at that moment. The look of sadness in his eyes seemed to indicate he didn't know what to do. It was as if I had suddenly struck him.

"I guess it's unpleasant to see something like this. But please stay. Just a little longer. We've no one to rely on. You're the only one we can trust."

"Oh, it hasn't been that unpleasant. It's just that I—" I wanted to say I couldn't stand being trusted. But I stopped for that would have sounded phony. In a situation of this sort, no matter how seriously I might have used such words, they would have been superficial. I had long stopped being in dead earnest about anything.

The couple recovered their composure and reverted to small talk. I sat ten more minutes before standing up.

"Can I join you for lunch next time? Frankly, the oysters I ate last night didn't agree with me."

The invalid was resigned, yet satisfied. A gentle expression was on his face.

"Please come again. I'll be waiting."

"I will. I'm glad I came. I like you both, more than I thought I would. I've really felt close to you."

That was true. I had sensed that they had been ashamed of themselves, that they were grappling, however hopelessly, with life in all seriousness. They had suffered between themselves long enough. After my words I saw a genuine look of pleasure light up the man's eyes. It wasn't an exaggeration to call it that. For quite a while I hadn't seen anything that simple and straightforward. He automatically offered me his thin hand, but he pulled it back fearfully.

She came with me when I was going downstairs. As she went alongside me, she was almost touching me.

"I was delighted you came today," she said, turning at once to face me before opening the downstairs door.

It seemed odd to hear her say, "Don't desert us, please. If you do, we won't forgive you! My husband will hold a grudge against you, and so will I!" Her words didn't sound that flippant, for apparently she had really given some thought to not being taken lightly. In fact, I found her words strangely profound.

"Don't be disgusted with me. Please protect me. Lend me some of your strength, and I'll come back to life again." She suddenly lowered her voice. "He may even die tomorrow. Understand?" Her eyelids narrowed over her eyes, which, ablaze with fever, were riveted on me.

As I went out the iron gate, firecrackers were going off everywhere, ringing in my ears. The next day would be the old calendar New Year. Red streamers were posted on the pillars and doors of every house. Some of the streamers had already been torn to shreds and were fluttering in the dust along the streets. Those fluttering scraps looked strangely vivid among the withered leaves and trash. A mother with her baby bundled up in a red cloth rode by on a rickshaw. Somehow those red colors seemed warm, mystical. As I walked back, I saw only the vivid reds of the festival. Men and women sat or walked or gathered in groups, their hands and faces dirty, their blue clothing worn out, filthy. Those men and women were trying to greet the New Year in some small way. For the first time apparently, I discovered that all these Chinese were living together, indifferent to me and other Japanese.

When I knocked at the back door, my landlady opened it. She smiled and then brought out a bottle of sake for me. If was a gift from the Japanese Self-Governing Council.

"You can celebrate the New Year," she said.

I took the bottle and went up to my room. The sake was sweet and thick. That night I had to finish a detailed report on a confiscated Japanese factory. I had to write in English or Chinese the name, serial number, and value of at least two hundred different kinds of precision machines. A catalogue and dictionary were on my crate. I made up my mind to buy some navel oranges with part of my fee. I would bring them as a gift when I visited the invalid.

By evening I was half-finished. I was drunk and tired. I felt a pain in my side, and my fingers could hardly move. My eyes kept getting weaker. Some men came into the alley to sell bread. A few came with pastry. All of them were Japanese reduced to becoming peddlers. No one bought anything from them.

Aoki dropped in. He wrote editorials for a Japanese newspaper.

"Why haven't you been to the Art Association meetings?"

"I haven't felt like it."

"The day after tomorrow the Cultural Division of the Chinese Control Office is calling everyone together. How about coming with me?"

"Can't. I've got documents to do." I couldn't help feeling how superficial the word "culture" was. Aoki kept on talking about the Chinese People's Court and other topics. They didn't interest me either. All I could think about were those yellow oranges I had seen, lustreless, piled high.

When Aoki left, I crawled into bed and tried to doze off. It was windy out, and someone kept knocking at the back door. I had a hunch it was for me. It was annoying to be plagued with callers. I heard a woman's voice. The thought rushing through me that she had come drove away my heavy, uncomfortable drowsiness. I sat up in bed. She was coming, coming! I was drunk. There was no telling how callous or even violent I would become.

She opened the door, and I heard her brown raincoat rustling, her outer clothing visible through it. Small drops of water sparkled minutely on her coat. "Just a second!" she said. She stepped over my bedding on the mats, unfastened the window, and quietly opened it. The dark grating was drenched with rain. "It's all right. He didn't follow me." She closed the window after peering down into the alley. "I bumped into Karajima on the street. I told him I was going to your place, and he said he'd come with me. I broke away from him and ran here."

Her wet cheeks were pale. She looked tired.

"Is he still hanging around?"

"Yes. I even met him the last time I was here." Her face was quite strained.

"He can't forget me. He said so himself. Strange, isn't it?—I brought you a snack. Have it with your sake."

"You came out just for that?"

"Yes. I really wanted you to have it." She took some teabiscuits from a black box. They were fried brown and looked homemade.

"Tomorrow's the New Year. I wonder if I can come see you?" she said.

I hadn't mentioned her sick husband, nor had she made the slightest reference to him.

"Quite free and easy, am I not?"

"Yes, free and easy." "Perhaps I'm slightly insane."

"A little," I said.

But I had my mind on Karajima. I wanted a detailed account of him. In spite of her reluctance he was what fascinated me.

"He's really all steamed up about you after all." "It looks that way." She showed her annoyance at my having mentioned it. "That conceited thing went so far as to ask me to save him! I was dumbfounded. It's too late for jokes like that. With the war crimes he's going to be charged with, he's really losing his mind."

"You mean he asked you to help him?"

"Odd, isn't it? A man asking a woman to help him out!"

That surprised me too. My only impression of Karajima was as the man of power you can't help despising. I had thought of him as an annoying insect, not as a man with feelings similar to my own. I didn't really loathe him—that is, I didn't really think about him. So I wasn't quite ready to accept her words at face value.

"It's not even a question of saving him. Since it's absolutely impossible for me to. Even if I could, I don't want to be dragged into the mess he's in. I definitely left him, you know, when the war ended."

She sounded phony to me. That was what she had said at our last meeting. I suspected her words were false, but she probably hoped they didn't sound that way.

"It strikes me he's not the type to scream for help. It's just that he needs you."

"I don't know about that. At any rate, I'm afraid. While he's alive, I can't sleep." She gave me the same look she had used at the door of her apartment. "Will you protect me? Will you love me? I love you."

"You mean—?" I might have felt overjoyed, but even then I wanted to equivocate. It was all so new. In contrast to me, she looked absolutely certain.

"I'm really in a difficult situation. You see that, don't you? So I'm quite serious. Don't lie. If you love me, say so. A half-hearted reply won't settle anything. I'm honestly in love with you."

"I love you. Of course I do. But maybe I can't protect you. I can't protect anyone."

"You love me then?"

"Yes."

"That's enough for me. That's fine. If only you do. Well, perhaps it's difficult for you to protect me." There was no malice in her smile. "You do seem lazy."

"I haven't had any experience along that line."

She grabbed my shoulders and stood up and kissed me. Her lips were quite soft. When she was about to move away, I put my arms around her and gave her a fairly hard kiss.

I felt she had planned this scene. I was certain she was following a script. But that didn't upset me. I didn't even feel I was being taken in. In fact, the thought that she was precious to me kept steadily increasing.

"But can you love me? Can you love a woman Karajima had?" Her eyes were riveted on me, her face oddly static, almost blank, because of her own passion.

"Love me! Think of me with pity! Oh, I want him killed! I wish someone would kill him now, right away!" Clinging to me and drawing her face close and sobbing quietly, she blurted out her threat. Apparently she couldn't control her feelings. All the while I continued holding her against me, I clearly recalled Karajima's face. He was no longer unrelated to me. Through her I was conscious of his body. He came so surprisingly close I could actually smell his breath.

"Before you said Karajima acted like he was coming here, didn't you?"

"Yes." She seemed caught up in some dark thought. "That's been his intention for a long time, I think. I'm sure of it."

"Alone? Why?"

"Probably to talk something over with you."

"But I don't know him that well."

"I didn't know you either, did I? Isn't that true? He suspects I'm relying on you. He's quite desperate. We have no time to lose."

"Is it that bad?"

"Yes. You've never had your life hanging in the balance, have you?"