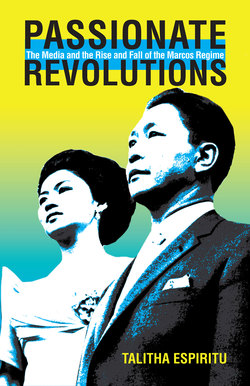

Читать книгу Passionate Revolutions - Talitha Espiritu - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

THE POWER OF POLITICAL EMOTIONS

The dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos came to an ignominious end on February 25, 1986. After twenty-one years in power, Marcos fled the Philippines following a four-day popular revolt dubbed people power. The euphoria in the streets was televised live around the globe. With the force of national allegory, these televised images conveyed a seemingly incontrovertible message: here is visible evidence that a people’s democratic aspirations can triumph over authoritarianism; here is proof of the utopian possibilities of political emotions.

The political spectacle of people power conjoins two stories, each one pivoting on the activation of emotion in the political sphere. On the one hand, there is the melodramatic story of how Marcos rose to power by creating a national family, a political fantasy that was both seductive and treacherous in its claims to transform the nation into a postcolonial utopia via a dictatorship of love. On the other hand, there is the story of how a sentimental culture of protest grew in close proximity to the “official” political sphere, an intimate public laboriously channeling the moral outrage of a people pained by the egregious excesses of the Marcos regime. The media figured prominently in both these stories. Marcos, after all, was a master of the political spectacle, and melodrama was both the mode and modus operandi of his statecraft. After the assassination of Marcos’s arch political rival, Benigno Aquino, Jr., in August 1983, however, the “freest press in Asia” came alive after a decade of state repression, galvanizing a “new politics” premised on affective displays of collective grief and concomitant demands for social justice. Meanwhile, the politicized auteurs of the so-called New Philippine Cinema engaged in unprecedented cultural activism both onscreen and in the streets. Combining melodrama’s proclivities for hyperemotionality with sentimentality’s faith in emotion as a direct conduit to affective truth, these forms of publicity were vital supports to the drama of emotional contestation that climaxed in people power.1

Marcos’s rise to power and the 1986 popular revolt bring into relief a problem perennially addressed in the “affective turn” in the field of social movement studies: the deeply entrenched fear of mass action as the irrational exercise of mob psychology.2 This fear turns on the normative split between the private and public spheres and the corollary pitting of feeling against thought. Emotions, according to this classic paradigm, belong in the intimate sphere. Their containment therein guarantees that the rule of reason will remain inviolate in the public sphere, understood as a scene of abstract debate. That these two “passionate revolutions” trafficked in ethico-emotional spectacles drawing heavily on melodramatic and the sentimental codes, points to what Lauren Berlant has described as the ascendance of a political culture of true feeling.3

Berlant sees an affective public taking the place of the mythical rational public imagined at the center of classic accounts of U.S. citizenship. Challenging the Enlightenment view of rationality as the distinguishing trait of the human subject, the culture of true feeling holds that what makes us human is our ability to empathize with the suffering of others. Elevating compassion to a civic duty, the culture of true feeling is premised on the notion that subjects are “emotionally identical in their pain and suffering and therefore imaginable by each other.” As the glue that holds an affective public together, an emotional humanism presumes that “to feel emotion x in response to injustice” morally authorizes one to participate in the political sphere. Paradoxically, however, this brand of visceral politics locates political agency in private emotional acts. It transforms citizenship into a form of spectatorship, in which the “citizen is moved rather than moving.” The culture of true feeling thus keys us to the consequences of a political epistemology that sees emotion as the “best material from which determinations about justice are made.”4

Berlant’s concept of “true feeling” is a productive starting point for thinking about the power—as well as the pitfalls—of political emotions in the two stories that I trace in this book. These stories are due for a critical reappraisal in light of a renewed interest in affect and emotion in the study of political cultures. Recent work on the Marcos dictatorship has indeed begun to explore the affective and emotional dynamics of political repression and dissent. Joyce Arriola’s work on print culture and Rolando Tolentino’s prolific writings on the cinema similarly see the conflict between Marcos and his critics in terms of a binary struggle between “official” and “popular” forms of nationalism, eliciting hegemonic and abject political feelings, respectively.5 With a much broader purview that explores the relations between Philippine visuality and the visual economy of an emergent world media system, Jonathan Beller’s analysis of the protest aesthetic of anti-Marcos filmmakers draws attention to the revolutionary potential of a social realism based on emotional excess.6 And engaging the cultural legacy of the Marcos regime from the perspective of queer cultural politics, Bobby Benedicto’s study of Marcos-era architecture productively highlights how the physical ruins of the regime’s film culture constitute an affective environment that articulates a “lost sense of progress, optimism and globalism,” while simultaneously bringing to light the indeterminacy of national identity.7 Passionate Revolutions builds on these important developments in the field. As a focused study of the role of the press and the cinema in the rise and fall of the Marcos regime, it seeks to explain how political emotions operate in official and popular forms of nationalism, and how these two affective realms intersect in the interfaces between national allegory, melodramatic politics and sentimental publicity.

National Allegory, Melodrama, and Popular Struggle

What is the relationship between nationalist movements and their symbolic forms? Berlant has coined the term “national symbolic” to refer to the range of discursive resources—icons, rituals, metaphors, and narratives—that constitute a culture’s shared language for constructing a collective consciousness.8 The national symbolic is what gives “official” nationalism its “heart”—and in the postcolonial world, its importance cannot be understated. In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon emphasizes the psychoaffective dimensions of this process that hinges on using national culture to “make the totality of the nation a reality to each citizen” and to “make the history of the nation part of the personal experience of each of its citizens.”9 The national symbolic, in other words, activates public subjectivity in the realm of fantasy. Here, the fractured and depersonalized colonized subject is restored to state of wholeness by an affective act of identification with an imagined national body.

Marcos’s many tracts on national culture echo Fanon’s polemic in Wretched of the Earth. Like Fanon, Marcos saw the importance of addressing the psychic wounds of the colonized subject, whose self-worth can be restored only via a program of cultural rehabilitation. This basic precept was the animus behind the regime’s cultural policy (see chapter 2). Let me signpost the affective dimensions of this policy here. Briefly put, it is not enough to have a cultivated mind; the task of national regeneration requires the citizen to have a reeducated heart. It is up to the state, then, to create a national culture that would provide a space of emotional contact, recognition, and reflection for its citizens. As a dramaturgical mirror designed to reflect back to the citizen an image of her best self, this national culture will transform the citizen into a subject of feeling: someone with affective commitments to the regime and its fantasy of a national family.

It has become a truism that Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos ruled the nation via a conjugal dictatorship that drew on the family form to secure its legitimacy.10 But much work still remains to be done to explain the complex relationship between the Marcos romance—the love plot that organizes the regime’s national symbolic—and the political and economic realities subtending the conjugal dictatorship. Two separate spheres, the intimate and the public, appear to be at work here, calling to mind related dichotomies: emotion vs. reason, representation vs. politics, and melodrama vs. documentary realism. On the face of things, these dichotomies appear to correspond with our habituated ways of organizing the disparate materials in the Marcos archive: films, literary works, and the ephemera of everyday life (what we in the humanities call texts) are studied with the interpretive approaches appropriate to the humanities, while the “hard facts” of state policy, political economy, and social movements are left up to social scientists to collect and narrate using the empirical methods of the social sciences. But if we were to take seriously the salience of “true feeling” in the political sphere, and if we were to take just as seriously the ways in which political-economic structures impinge on the national symbolic, we would see the necessity of rejecting these dichotomies in favor of a more interdisciplinary approach that blends fact and interpretation. Considering the Marcos romance as a national allegory is an important first step.

As a critical concept and political methodology, national allegory has become a prominent fixture in postcolonial discourse, particularly in Latin America. Ismail Xavier’s pathbreaking study of Brazilian cinema fruitfully traces the rise of national allegory as a militant cultural practice in the 1960s and 1970s, a time “when the movement in world history seemed to elect the so-called Third World as the epicenter of change.” In Brazil, this convulsive moment resulted in films that sought to “present a totalizing view of the country,” with a clear “preference for allegory.”11 As both a “source of knowledge” and the “embodiment of a critical view of history,” national allegory encapsulated an aesthetic and political predisposition toward creating social texts with a totalizing rhetoric anchored in a specific ideological-political conjuncture—one in which “the issues of class, race and gender were subordinate to the national question,” and the notion of “underdevelopment was the nucleus of national thinking.”12 National allegory, in other words, became the medium for analyzing—and intervening in—the postcolonial condition and the failure of the national dream.

The notion of underdevelopment resonated in the Philippines in the early 1970s, when Marcos and his critics were locked in a power struggle that culminated in his declaration of martial law, in September 1972. At the time, the dominant framework for apprehending the “national question” in the Philippines was the neocolonial, or dependency, model.13 Leftist nationalists argued that the economic practices of transnational corporations instantiated the indirect colonial rule of the United States over the Philippines, which was reinforced by the military pacts between the two countries. The nation’s dependent status vis-à-vis an external military and economic power consigned it to a condition of underdevelopment that could be corrected only by radical social transformation.

When Marcos became dictator, he assumed the position of the nation’s “official writer,” as Arriola puts it, “mix[ing] state policy with ideology and propaganda to rally the people toward a ‘nation.’”14 Marcos went so far as to “author” Tadhana: The History of the Filipino People, a multivolume series that was touted to be the definitive history of the Philippines. In it, Marcos answered his critics’ gloomy prognosis with a self-affirming narrative of a postcolonial nation overcoming all odds.15 Tadhana’s “official history” resonated with Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos’s own biographies, which were meant to be read as autobiographies of collective experience. Complementing Tadhana’s affirmative narrative, they present Ferdinand and Imelda’s dreams, struggles and triumphs as allegories of the nation’s colonial past, unstable present and optimistic future. They present the couple’s intimate union and political partnership as a rule of love, the social solution to the nation’s condition of underdevelopment.

In the Marcos regime’s political lexicon, love is a euphemism for modes of social control secured in and through cultural policy. It bears noting that cultural policy straddles the intimate and public spheres: insofar as it is primarily concerned with the normalization of tastes and the regimentation of social conduct, cultural policy requires the alignment of the intimate sphere of domesticity with the public culture of the state. The two spheres are assumed to work in tandem, inculcating a drive toward self-improvement in the cultural citizen. And as Jürgen Habermas reminds us, it is in the domestic sphere where citizens are prepared for their critical social function in the public sphere, where the public’s role as critic is guided and made possible by the ideal of collective intimacy.16 Cultural policy indeed turns on what Berlant, after Habermas, calls “the migration of intimacy expectations between the public and the domestic.”17 Simply put, it assumes that the cultivation of good taste in the intimate sphere leads to good citizenship in the public sphere. What is striking about the cultural policy of the Marcos regime is its allegorization of this classic model of the ethico-aesthetic in the person of Imelda Marcos, who, as “mother of the Filipino people,” was the primary civilizing agent of the national family. This book unpacks Imelda’s complex and highly ambivalent role as the melodramatic heroine of the Marcos romance whose desire for the good life encapsulates the melodramatic imaginary of the regime’s cultural policy.

Melodrama is a constitutive feature of the allegorical impulse to narrate “the truth” of a nation. Indeed, the overlap between national allegory and melodrama is of central concern to my project, and a brief explication of their mutually reinforcing dynamic is in order.

As a critical concept, melodrama is a notoriously slippery term. Since the 1960s and 1970s, when melodrama emerged as a major topic in film studies, scholars have tried to pin down its essential qualities. But so many inconsistencies abound in the usage of the term, and so many mutations have surfaced in its cross-media adaptations that no consensus has been reached on whether melodrama constitutes a coherent genre or a more elusive “mode” of expression.18 Recent scholarship has shifted the terms of debate from what melodrama is to what it does.19 Whether scholars approach it as a specific genre, or engage it as a pervasive mode of popular culture narrative, all agree that it is particularly responsive to experiences of dislocation and trauma.20 All agree, furthermore, that its key features—strong pathos, moral legibility, and sensational expressionism—resonate with subaltern audiences, or those among us whose material vulnerability and experiences of social marginalization have been most acute.

Emerging in the wake of the Enlightenment, melodrama, Peter Brooks argues, seeks above all to make moral principles legible in a secular world, where “the traditional patterns of moral order no longer provide the necessary social glue.” It has long been the job of melodrama to serve a compensatory, quasi-religious function, defusing social anxieties with stories enacting the “eventual victory of virtue.”21 But as Linda Williams has more recently argued, the force of melodrama’s ameliorative function rests not so much on a drama of the defeat of evil by good but on the “all important recognition of a good or evil that was previously obscure.” Indeed, what melodrama really does is to allow us to see “a previously unrecognized problem or contradiction within modernity” and to “generate outrage against realities that could and should be changed.”22

These insights allow us to apprehend melodrama as a discursive practice that is also mode of social activism: it is a means of “[making] truth and justice legible by demanding a clear binary between right and wrong.”23 Melodrama does not simply reflect a mode of consciousness in a postsacred world; it acts upon that consciousness by supplying a “dominant language on the modern conduct of public life and politics.”24 This book contends that melodrama fundamentally structures the key operation at the heart of all national allegories: the impetus to reveal the “truth” of the nation in a mode that appeals to the affective reason of the citizen.

Discussions of melodrama’s aesthetic force often turn on the notion of excess. In melodrama, exaggerated emotionality and a predilection for spectacle combine to produce an overwrought drama that “produces and foments psychic energies and emotions.”25 Ultimately, melodramatic excess constitutes a sensational economy that activates a complex process of psychological identification for the viewer.

Central to the discursive practice of melodrama is the presentation of victimization. Almost without exception, moral virtue is signified by pathos and suffering. Melodrama’s sensational economy triggers two interrelated processes: a heightened perception of moral injustice (against an undeserving victim) and the cathartic transformation of raw emotions (of distress and moral outrage). The audience feels strong pathos, “a sort of pain at an evident evil of a destructive or painful kind . . . the evil being one which we imagine to happen to ourselves.”26 The pathos that accompanies melodramatic identification, in short, is a form of self-pity.

The psychoaffective processes of melodrama have a powerful ideological effect. As many critics have noted, melodrama has a conservative social vision: the suffering of the victim must be vindicated through acts of redemptive violence, which then restores a community to its lost “space of innocence.”27 But as Matthew Buckley has recently pointed out, the critical tendency to privilege melodrama’s redemptive social vision obscures the genre’s complicated affective conditioning. Melodrama, he reminds us, initially invites sympathetic attachment to victimized heroes and heroines. However, opposing emotions of hatred and fear ultimately supersede feelings of sympathy, as negative affects are “projected or ‘dumped’ outward . . . upon some clear other, through angry and often violent action.”28 A radical disconnect thus emerges between the consoling vision of melodrama’s moral structure and the violent projections of its affective structure. The latter, to borrow Buckley’s terms, encourages “infantile processes of defensive withdrawal,” substituting “the passive consumption of sensational fantasy for the more complex and demanding performance of collective identification and communal action and identity.”29

A fundamental tension exists, then, between melodrama’s two core operations: the imperative to move audiences to feel moral outrage against social contradictions, and the validation of traditional figures of political authority, who ultimately emerge as the real agents of moral retribution. While the former registers melodrama’s implicit drive toward social activism, the latter speaks to melodrama’s opposing tendency to reduce political action to the spectatorial pleasures of mass entertainment. The push-pull between these two melodramatic operations was amply in evidence in Marcos’s rise to power and in the 1986 popular revolt.

This book unpacks the melodramatic politics inhering in the national allegories created by Marcos and his critics. It locates these allegories in press reports, magazine features, campaign biographies, propaganda films, biopics, and studio films that serve as melodramatic transcripts of the rise and fall of the Marcos regime. These allegories bring to the fore the continuing salience of a fundamental question, first broached by Ana Lopez, that continues to inform studies of melodrama in non-Western contexts: “Is it possible that this form, the product and instrument of the dominant classes and the servant of dominant ideologies, can be utilized and read as a positive force for socio-cultural change in dependent societies?”30

Media scholars and practitioners have routinely attacked melodrama as a retrograde cultural form, “helping to produce the ‘perfect’ subject of political and economic dependence in the Third World.” But as Lopez cogently argues, these naysayers are blindsided by melodrama’s special affinity with the popular classes. Exactly how these melodramas “meet the real desires and needs of real people” is the crux of the problem.31 Uncover that and we might begin to analyze melodrama’s critical potential as a site of resistance in Third World societies. More recently, Sheetal Majithia has problematized the implicit privileging of reason over emotion, the secular over the sacred and the West over the non-West in melodrama studies. Postcolonial melodramas, Majithia argues, show how powerful political attachments are formed through the affective reason activated by melodrama: the way it illuminates “our power to affect the world around us and our power to be affected by it.”32 Susan Dever also sees the democratic potential of melodramas, which may “provide a means for newly-enfranchised subjects to reflect—both cognitively and affectively—on the significance of their participation in nation-states whose sacred legitimacy revolution has called into question.”33 Building on these insights, this book examines how melodrama can channel the desires of disempowered groups to articulate a popular democratic politics in resistance to the elitist and paternalistic discourses that dominate “Philippine-style” democracy.

As Reynaldo Ileto argues, the history of political struggle in the Philippines has been characterized by the coexistence of two competing notions of politics: pulitika, the deficient formal democracy of the elite, and the more “meaningful politics” of the oppressed. Dismissed by elites as mere “emotional outpourings,” the latter produced numerous popular uprisings galvanized by such concepts as awa (pity) and damay (empathy) for an aggrieved person or community.34 Popular forces, in short, have understood political struggle as melodrama. And here, the social and the political become legible only “as they touch on the moral identities and relationships of individuals.”35 As I demonstrate in this book, the national allegories of the oppositional media engaged the audience’s visceral capacity to recognize the pain of the popular forces as proof of virtue. They denigrated the civic ardor of those still invested in pulitika as the chicanery of a debased democracy. Such denigration of “official” politics is a clear indicator of the sentimental ethos animating the anti-Marcos movement. But despite its concerted efforts to distance itself from Marcos, the movement shared with the dictator an unwavering faith in the logic of true feeling. As we shall see, a sentimental politics based on compassion is not qualitatively different from Marcos’s own claim to govern the nation with love.

National Sentimentality: Once More, with Feeling

What is the place of painful feeling in the making of political worlds? Berlant’s work on “national sentimentality” centers on this question, which resonates in my reading of the national allegories documented in this book. Let me briefly outline the central premises of the concept and explain how they inform my methodology.

Berlant describes national sentimentality as a mode of political rhetoric that makes a captivating promise to its public. Simply put, it promises that the social injustices fracturing a nation will be put to right through the power of empathy and identification. This promise comes out of the long-standing contest between two models of citizenship that roughly correspond to the above description of pulitika and the “meaningful” politics of the oppressed. On the one hand, there is the classic model of citizenship that sees the value of each citizen to lie in their juridical status as an abstract person before the law. On the other hand, there is a sentimental model of citizenship that Berlant traces back to the labor, feminist, and antiracist struggles in the United States in the nineteenth century. These social movements imagined a nation peopled not by abstract persons but by “suffering citizens and noncitizens” structurally excluded from the “American dreamscape.”36 Lest we forget, the U.S. Constitution constructed the person as the unit of political membership in the American nation, but in practice, this privilege really only belonged to white, property-owning males. The notion of national identity thus serves to protect the implied whiteness and maleness of the original American citizen, whose privilege it was “to appear to be without notable qualities.” Indeed, the notion of abstract personhood so dear to the classic model of citizenship presupposes a white male body as the relay to legitimation. And the power to suppress this body becomes the measure of one’s authority in the public sphere.37

Sentimental politics turns the classic model of citizenship on its head, positing the pain of subaltern subjects—those who have never had the privilege to suppress the event of the body—as the true core of national collectivity. It insists that a utopian society can be achieved by identification with their pain. Note, however, that a power imbalance supports this transaction of pain and recognition, which is focalized from the perspective of the culturally privileged. The pain of African-Americans, women, and the poor “burns into the conscience of classically privileged national subjects, such that they feel the pain of flawed or denied citizenship as their pain.”38 Sentimentality, in short, assumes that structural social change is possible, provided that a bond of compassion—“an affective and redemptive linkage”—can be forged “between the privileged and the socially abject.”39

What creates the bond of compassion? The short answer: sentimental publicity. Sentimental citizenship abhors the “official” institutions of politics. It locates its interventions not in the political domain but “near it, against it, above it,” in the “juxtapolitical” space of everyday life, whenever and wherever an intimate public forms around scenes and stories of social injustice. Books, newspapers, films, TV, and all other forms of popular narrative are the diverse media of sentimental publicity. They provide the material infrastructure for circulating sentimental narratives and for gathering an intimate public together—whether physically, as in the case of the gregarious communitas of cinema spectatorship, or imaginatively, as in the case of the solitary reader/viewer who imagines a shared horizon of experience with other readers/viewers of sentimental texts.

But it is a sentimental aesthetic that allows sentimental narratives and their representations of social wrongs to gain political traction within this intimate public. And this aesthetic is defined by the use of personal suffering to “express or exemplify conflicts in national life.” In sentimental narratives, stereotypes and clichés imbue a “local drama of compassionate attachment with a sense of import beyond the scene of its animation.” The struggle of an individual thereby takes on the expansive and totalizing logic of national allegory. And when crises of the heart are resolved, the “emotional justice achieved on the small scale figures its resolution on the larger.”40

The sentimental aesthetic seeks to transform its privileged public. It elevates reading to a powerful act of compassionate cosmopolitanism: to read a sentimental text is to enter a space of dis-interpellation insofar as one is compelled to identify with someone else’s pain. Identification with suffering is indeed the only ethical response to a sentimental plot. Liberal empathy—the idea that you will never be the same—is thus the “radical threat and great promise” of the sentimental aesthetic. It embodies the ethico-aesthetic project of cultural policy writ large: the idea that “proper reading will lead to more virtuous, compassionate feeling and therefore to a better self.”41

Again: sentimental publicity locates compassionate citizenship in the transactions of pain and recognition that bind the members of an intimate public. But resting primarily on an aesthetic activity, sentimental publicity generates a mode of citizenship that does not easily map onto the political sphere, if we understand the latter as a “place of acts oriented towards publicness.” What we get instead is a “world of private thoughts” projected outward. This, in essence, is what a sentimental public is: “private individuals inhabiting their own affective changes.”42 This brings us to the “unfinished business” of national sentimentality as Berlant sees it: how do changes in feeling, even on a mass scale, bring about structural social change?

This book seeks to weigh in on this question from the postcolonial perspective of the Philippines during the historically significant period of the Marcos dictatorship. A critical feature of my methodology is to draw attention to the process of rough translation that has accompanied the transplantation of U.S. models of democracy and cultural policy to the former colony. These rough translations attest to what Majithia describes as the “coeval but uneven conditions that characterize postcolonial and global conditions.”43 Taking a relational perspective indeed allows one to appreciate how the sentimental political culture described by Berlant also inheres in a nation-state conceived in the image of the United States. It allows us to see how political attachments in these two distinct—but profoundly interconnected—national contexts often “derive from visceral and inchoate fears, resentments, anxieties, desires, aspirations, senses of belonging or non-belonging that an individual (or an ideal, or an organization) somehow stirs up and addresses.” It also allows us to see how the structurally oppressed and the socially abject in both countries “often have strongly conflicted sentiments about themselves and the society that has made them ‘other.’”44

This ambivalence was certainly a concern for Marcos, who often referred to the shame and self-hatred of the colonized subject. But he was also wont to invoke the rage of the oppressed, stressing how this protorevolutionary emotion could have dire consequences for the republic. The containment of this terrible rage was indeed Marcos’s pretext for declaring martial law. Meanwhile, there were limits to the anti-Marcos movement’s sentimental will to correct social wrongs. From the earliest days of the dictatorship, the various “pain alliances” that comprised the anti-Marcos coalition were internally torn between those who sought radical social change and those seeking the more moderate solution of a regime change. These factions, however, stood united—however briefly and tenuously—in the belief that a compassionate public feeling was a necessary first step toward social transformation. But the deciding factor was the popular classes: Marcos and his critics routinely invoked their rage and pain and sought to control it. Both sides sought to create a sentimental bargain with the popular classes. To borrow Berlant’s terms, this involved “substituting for representations of pain and violence representations of its sublime self-overcoming.”45 Both sides however, evinced a profound lack of knowledge—distrust, even—of the popular classes. In recreating the story of Marcos’s rise and fall, I emphasize the double representation of the popular classes—as simultaneously abject and politically volatile—as a case study of how, as Deborah Gould puts it, the ambivalence of the abject and the marginalized “shapes a sense of political (im)possibilities,” and can have “tremendous influence on political action and inaction.”46

The above discussion of sentimental publicity makes clear the importance of engaging the aesthetic dimension of sentimental texts. The sentimental ideal of liberal empathy indeed grounds the various national allegories that I analyze in this book. I explicate how these texts imagine social transformation not as a structural event, but as an emotional one: how the ability to feel for the subordinate other is presented as something that progressively grows into a desire for the emancipation of that person, and by extension, the community. However, as Berlant warns, an overinvestment in the emotional event of the reader’s psychological transformation, at the expense of tracking what is needed for structural change, confines sentimental politics to the business of “delivering virtue to the privileged.”47 It thus behooves us to analyze these sentimental texts alongside the “official texts” of government (presidential decrees, congressional speeches, white papers, conference proceedings, etc.), and to place them in their proper historical and social contexts. For indeed, the “pain politics” of sentimental culture “falsely promises a sharp picture of structural violence.”48 It is necessary, therefore, to bring the political economy of the regime to bear on our discussion of the sentimental politics of the anti-Marcos movement. Lest we forget, feeling is a powerful but unreliable measure of justice.

With a historical sweep that spans twenty-one years of the Marcos era, this book presents the stories of two “passionate revolutions.” Chapters 1 through 3 examine Marcos’s so-called “democratic revolution,” while chapters 4 through 6 trace the story of people power. Chapter 1 examines the protest culture of the Philippines on the eve of martial law. I reconstruct the volatile political climate generated by the so-called First Quarter Storm, the violent street protests that rocked the nation in early 1970. I read the national allegories on display in these protests, as memorialized in Jose F. Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage. Consisting of Lacaba’s first-person accounts of the protests for the Philippines Free Press, the iconic text captures the visceral performance of moral clarity at the heart of sentimental politics.49 But the sentimental publicity that enabled Marcos’s critics to become an intimate public finds a counterpart in his command of political spectacle. I examine a rare propaganda film, The Threat—Communism, which draws on the U.S. tradition of “political demonology” to contain the revolutionary sentiments then sweeping the nation. The film is a perfect illustration of the affective conditioning that constitutes melodrama’s negative pole, and constitutes a hermeneutic key for making sense of Marcos’s pivotal declaration of martial law, in 1972.

Chapter 2 examines the cultural policy of the Marcos regime. I tease out how Marcos’s cultural liberation program mimicked the paternalistic rhetoric of the colonial policy of benevolent assimilation: both decreed the ethico-aesthetic training of cultural subjects as a prerequisite to the exercise of the rights and duties of citizenship. But Marcos’s cultural liberation program also echoed Fanon’s theorization of cultural rehabilitation in The Wretched of the Earth: the cultural imperative to correct the “self-contempt, resignation and abjuration” of the colonized and thereby effect the psychoaffective creation of “new men.”50 Marcos’s New Society was indeed an ambitious cultural-policy endeavor that sought to create the New Filipino by synthesizing the paternalist, U.S.-centric and neocolonialist discourse of modernization with the populist, nationalist, and anticolonial cultural politics of an emergent Third World consciousness. The chapter revisits the Marcos romance, showing how this love plot underpins the regime’s national symbolic and its double-speaking cultural policy.

Chapter 3 examines the impact of the regime’s cultural policy directives on the cinema, beginning with a “national sexuality” campaign against a bomba (sex-and-violence) film culture that mirrored the irrational and libidinous excesses of Philippine politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I trace how a dual policy of strict censorship and artistic promotion—and Imelda’s “internationalist” aspirations for the cinema—would ironically lead to the consolidation of a cinema vanguard committed to raising awareness of political repression in the New Society among a world audience. Their antiauthoritarian cultural politics bore a striking affinity with the protest culture of the First Quarter Storm. I tease out the resonances of the First Quarter Storm and the bomba film culture in Lino Brocka’s Tinimbang ka ngunit kulang (Weighed and found wanting, 1974), a sentimental text that allegorizes social cleansing in the New Society.

Chapter 4 traces the various fronts of the anti-Marcos struggle from the earliest days of martial law to just before the Aquino assassination. I situate the movement’s pain alliances against the political-economic backdrop of the Marcos regime’s disastrous development initiatives. I read Behn Cervantes’s Sakada (1976) as a sentimental text that self-reflexively reveals the paternalism of both radical and moderate factions of the anti-Marcos movement toward the oppressed groups in whose name the struggle against dictatorship was being waged. The film begs to be read against the real-world activism of the popular classes. I thus examine two cases instantiating “democracy from below” in the New Society: the struggle of the Kalinga and Bontoc mountain peoples against militarization and the struggle of urban squatters against their forced displacement from Imelda’s so-called City of Man. With only the New Cinema, the Catholic media, and a handful of defiant journalists in the controlled media to publicize their causes, these communities fought at a disadvantage for the very ideals that Nathan Gilbert Quimpo identifies as the salient goals of democracy from below: “popular empowerment, a more equitable distribution of wealth, and a more participatory democracy.”51

Chapter 5 examines the “quiet revolt” of the establishment press, the return of the bomba film, and the sentimental publicity occasioned by the Aquino assassination, in 1983. Marcos’s failing health and a succession struggle within the national family had emboldened journalists within the controlled press to expose the military’s human-rights abuses. Meanwhile, the sensation stirred by the screening of pornographic films at the 1983 Manila International Film Festival brought into relief the growing fault lines in Marcos’s “household” and propelled cultural workers to organize against the regime. I reconstruct the Aquino assassination as the melodramatic event that compelled the various factions of the anti-Marcos struggle to close ranks. I show how national grief transformed the elite politician into the martyr of a new sentimental politics.

Chapter 6 examines the dramatic escalation of protest activity after the assassination. I show how the melodramatic mass-action strategies of the movement hinged on stoking the class hostilities of the popular classes—and, crucially, transforming mass anger into a politically viable expression of resistance. I examine the activism of New Cinema filmmaker Lino Brocka and present a close reading of Bayan ko: Kapit sa patalim (My country: Seize the blade, 1985), his homage to the new politics. As a bellwether of the 1986 popular revolt, this national allegory offers valuable insights into the often-overlooked role of the popular forces in the unfolding of people power.

Contrary to the dominant interpretation of the 1986 revolt as a middle-class phenomenon, people power was in fact the culmination of the long popular struggle against the regime. Various grassroots struggles from the earliest days of martial law created both a melodramatic imaginary and an infrastructure of resistance that allowed millions of disempowered Filipinos to stage an awesome public drama bearing the full force of twenty-one years of resistance against a repressive and corrupt regime. The mobilizing efforts of an alternative press and the New Cinema were crucial supports in this drama. But at bottom it was the overwhelming presence of the popular classes and their melodramatic performances of their democratic aspirations that were on display. It was, in short, the force of national allegory that toppled the dictator.