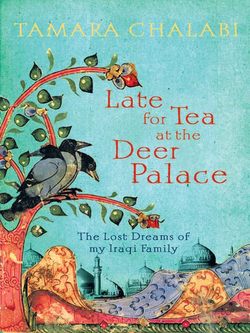

Читать книгу Late for Tea at the Deer Palace: The Lost Dreams of My Iraqi Family - Tamara Chalabi - Страница 13

Duty Calls

ОглавлениеA Busy Day for Abdul Hussein

(1913)

ABDUL HUSSEIN CHALABI rose early, performed his ablutions, uttered his prayers unto Allah and the Prophet, then sat down to a large breakfast of his favourite food in all the world: fresh gaymar, cream of buffalo milk, velvety-smooth in texture, spread over just-baked bread and crowned with amber honey from the Kurdish mountains.

He was still tired. He had slept poorly and his troubled dreams had been of his dead sister. In them, she had stood silently before him, her eyes burning with reproach. He had tried his best to appease her, to explain that the family’s decision had really been for the best. She had opened her mouth as if to speak, and then he had woken with a start. Alone in his bedroom, he had taken a few minutes to recollect himself before rising.

Feeling better for having eaten, he adjourned and sat with his head thrown back while his butler shaved his plump face. He could hear his mother, Khadja, barking orders at her servant across the long corridor that led to her quarters. Once shaved, he dressed as always after breakfast – never before – so that the belt of his cloak would not cramp his enjoyment of the best meal of the day. At the age of thirty-seven, Abdul Hussein remained very particular about his appearance, forever sending the servants into panic attacks with his complaints of poorly-ironed shirts and badly-polished boots.

He wore the typical attire of a sophisticated urbanite: a traditional robe tailored in Baghdad from sayah, a delicate striped cotton material bought in Damascus, over white drawstring trousers. On his head he wore a fez, decreed by the Sultan in Istanbul to be the appropriate headgear of the modern Ottoman Empire. Abdul Hussein not only embraced this symbol of modernity; he believed that it suited his full face rather better than the old-fashioned keshida still sported by his eldest son, Hadi. A cloth wrapped around a conical hat, the keshida was also much more cumbersome than this new headgear. As a final indulgence to vanity Abdul Hussein smoothed the hairs of his moustache with a small bone comb he had purchased in Istanbul.

Oil portrait of Abdul Hussein Chalabi.

As for any powerful and influential man, his day was ruled by a rigorous schedule. He barely had time to browse the morning papers before a servant came to inform him that at least ten people awaited his presence in the dawakhana, the formal drawing room in the men’s quarters of the large yet overrun house.

As a mark of his status it was Abdul Hussein’s lot to sit and receive men all morning in the dawakhana, a ritual chore inherited from his father and from the grandfather he had never known. Men came to him in need of services, favours and assistance. They presented him with their problems concerning their lands, the government, the tribes, the mullahs, the weather, even – on occasions – God Himself. Abdul Hussein would sit in a wooden armchair and listen carefully as the chaiqahwa, the tea-coffee boy, made his rounds of the assembled visitors.

Today, his enthusiasm for the job in hand was at a particularly low ebb. He was still unsettled by reports of the Ottomans’ latest defeat in the Balkan war and the subsequent loss of the majority of the Empire’s European provinces. At a meeting in Baghdad the previous day, the Governor had broken the bad news to the Mejlis-i-idare-i-Vilayet, the advisory council for the Baghdad Vilayet, of which Abdul Hussein was a member. The prognosis was dispiriting; the Ottoman Empire was in decline.

A servant interrupted his thoughts with a message from the house of his sister Munira. She was married to Agha Muhammad Nawab, a wealthy Indian Shi’a notable who, Abdul Hussein learned, had just returned from a long trip to India. Abdul Hussein read in the note that Munira had recently taken delivery of a new arrival, which, the Nawab promised, would interest him greatly. He sent his sister a reply to let her know to expect him for lunch. Today’s challenge would be to discharge his duties as swiftly and shrewdly as his wits would allow him so that he would be free to call on the Nawab in the afternoon.

The dawakhana began with the usual exchange of greetings. Ibrahim, the wiry manager of one of Abdul Hussein’s estates, was waiting to give him his weekly report on the progress of the crop in one of his citrus and pomegranate orchards, which lay north by the river. Although Abdul Hussein had visited the land only a few days earlier, he could always rely on Ibrahim to show up with something fresh to complain about – any excuse to visit the dawakhana. Addressing Abdul Hussein as hadji in reference to his recent pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibrahim began to explain the reason for his presence.

He complained that the Bedouins were cutting the telegraph lines again – he had even caught one them using the lines to tie goods to his donkey – and that his men were having to waste their time throwing the nomads off the land, while the authorities did nothing to tackle them.

Abdul Hussein knew his manager was right – that over the past few decades the area’s administrators had fallen into slipshod ways; the vandalism of the telegraph lines was only part of an ongoing problem which the Ottoman Governor had not been able to resolve. Whenever there was a lull in security, the desert tribes attacked the towns. Lying a few miles to the north-west of Baghdad, across the River Tigris, Abdul Hussein’s home town of Kazimiya’s proximity to the open desert to the north made it vulnerable even though, like Baghdad, it had walls and gates that were meant to protect it.

Abdul Hussein felt frustrated that he could not do more himself to maintain public order. But the grand old days when his family had been Kazimiya’s rulers had passed. The family surname, Chalabi, was an honorific title that came from the Turkish Çelebi, a term which had several meanings, amongst them ‘sage’, ‘gentleman’ and even ‘prince’. It had been bestowed on the family when they had administered the region for the Ottomans. As direct rule had been imposed on these parts by Istanbul some decades earlier, the Chalabis no longer performed those duties, although they remained at the heart of Kazimiya’s political and social life.

Ibrahim’s father had worked for Abdul Hussein’s powerful father Ali Chalabi, and Ibrahim had grown up hearing stories of the latter’s iron fist and courage. Ali had been feared in Kazimiya, even hated by some, but he was admired by Ibrahim: this much Abdul Hussein knew. And so Abdul Hussein could hardly object when Ibrahim decided to share with the dawakhana a story he had heard concerning Ali’s ingenuity.

Abdul Hussein’s younger brother Abdul Ghani joined them as Ibrahim began to tell their guests how, one day many years ago, news reached Kazimiya of a plague of locusts that was approaching the city from the north. The sight was terrifying: a cloud of dark green insects rolling towards them at startling speed. No force on earth could push them back, making the townsfolk panic as they prepared to ride out the attack behind locked doors. Many had already resigned themselves to losing their crops, and with them their annual profit, but not Ali effendi. That year he had decided to plant a new crop of tomatoes. Determined to save them, he summoned the farmers to discuss what could be done. Then he threw his camel-hair cloak, his abaya, to one side and paced up and down his land for two days in his muddy boots. His guards followed him, their rifles on their backs. Shaking his head, Ibrahim said, ‘None of his employees had ever seen him behave like this.’

The rumour spread around Kazimiya that the great Ali Chalabi had gone mad. Witnesses described how he would stop in his tracks, scratch his dark beard, look up to the sky, turn around and resume his pacing. By the second day, his guards were wilting in the heat and gave up marching after him, yet Ali was so distracted he didn’t even notice. Suddenly, they heard him shout, ‘I’ve got it! I’ve got it!’

Ali Chalabi, seated centre, holding his youngest daughter, surrounded by family and friends.

He ordered his men to go to all the markets and buy every single mud pot they could find. ‘And don’t you dare tell anyone what you’re buying the pots for!’ he added. Intimidated, his men scoured every market in Baghdad. As soon as one returned with a batch of pots, Ali would send him off to buy more. When he had laid his hands on every pot in the area, he ordered the farmers to take them and cover every single tomato plant, hiding them from the locusts and making his fields look like a pockmarked sheet of baked mud. No one else in Kazimiya had thought of the idea, and when the locusts arrived the next day all the crops were ruined except for Ali’s tomatoes. He made a fortune.

‘Allah Yirahamah, may he rest in peace. We need men like him today to guide us through these changing times,’ Ibrahim concluded. Abdul Hussein had never approved of his father’s severe nature, but he knew what Ibrahim meant. The teetering Ottoman government had been radically transformed in 1908, when a group of nationalist Turkish army generals – the ‘Young Turks’ – had seized the reins of power from the Sultan in Istanbul, limiting his role and facilitating a new constitutional era. The events of 1908 had at first brought with them a new energy, promising freedom and equality for the many multi-ethnic communities of the Empire. But gradually it became clear that the Young Turks were promoting a European-style nationalism, with Turkishness as its main identity. The Arab people of the Ottoman Empire had begun to feel increasingly marginalized and disadvantaged as swathes of secular modernity swept through the Empire to the west of them.

Abdul Hussein had entertained certain hopes for the modernizing projects proposed by Istanbul. On paper, the proposed German-engineered Berlin-to-Baghdad railway had been more exciting than anything the locals had dreamed of … but now, what of it? The Germans were still viewed positively as an advanced industrial people who had come to help develop Mesopotamia, yet very little track had actually been laid since the project’s inception a year ago. Many pieces of machinery already lay abandoned, surrounded by rubble, collecting dust or rusting. To Abdul Hussein it was a source of bewilderment that even deepest Anatolia had already been linked up to the rest of the world by rail. Why not us? he wondered.

He could see that new ideas did not grow as freely or as quickly in Baghdad as in Istanbul, for all the new cafés, newspapers and government schools that were now springing up. Kazimiya was even slower to embrace change, partly because it was a Shi’a shrine town and therefore more religious in outlook. Abdul Hussein felt as many did that this backwardness was enforced from above, as a consequence of the town’s predominantly Shi’a character: under an Ottoman system dominated by the Sunnis the Shi’a were never going to receive their proper due. Politically they were weak, and everybody knew it.

He sensed a haughtiness and disregard among Ottoman officials when it came to his people and this land. Midhat Pasha had been the only governor to do anything for Baghdad, but he had left the area in 1873, three years before Abdul Hussein was born. The new constitutional reforms, with their accompanying bureaucratic language, threatened to alienate Abdul Hussein from his own heritage. And now he had to shed his claim to it, because in the eyes of central government he was an Arab from Kazimiya. Yet he considered himself every bit as Ottoman as any Istanbuli, whether they liked it or not.

Next, an anxious young man introduced himself as coming from Baghdad and explained that he was visiting the dawakhana with a common acquaintance. Clearly upset and frustrated, he said that he had been attacked earlier that morning by some robbers in Agarguf, an archaeological site located in the desert outside Kazimiya. Like Ibrahim, he blamed the government, and complained to the dawakhana about poor security, poor governance … Abdul Hussein soothed the man, and called one of the servants to attend to him and, when he had rested, to hail a rabbil, a carriage, for him from the station down the road.

No sooner had Abdul Hussein turned around than another man raised his voice to air his grievances. His brother had broken his shoulder in an accident the previous week, and he wanted to claim compensation from the trammai company, in which Abdul Hussein and his family were major shareholders. The tram tracks were now more than thirty years old, and – like all else in the locality – suffering from government neglect. ‘May God heal your brother!’ he reassured the claimant. ‘We will give him compensation, don’t worry.’

Over the next couple of hours Abdul Hussein listened carefully to a torrent of requests and concerns, at times instructing his clerk to note down information for him to follow up. His visitors were more than living up to the locals’ reputation for cool nerves and slow conversation. The Kazmawis, the townsfolk of Kazimiya, were not nicknamed ‘cucumbers’ for nothing.

Finally his steward Sattar burst into the room to tell him that he was awaited at the shrine, where he had promised to be by noon. Abdul Hussein apologized to the remaining men in the dawakhana. All nodded knowingly; when the shrine called, everyone heeded. The men rose in unison to say their goodbyes.

The Baghdad–Kazimiya tram, circa 1910.

Abdul Hussein went to the shrine with Sattar on foot. The ten-minute journey would have been difficult to negotiate in his preferred mode of transport, his Landau carriage. Instead, the two men manoeuvred their way through dark unpaved alleyways until they reached the first fruit and vegetable stalls on the fringes of the main square. An old woman was selling baklava, struggling to bat away the flies that buzzed around her tray of wares. The overpowering smell of the market assailed them, the stench of the dirt on the ground mixing with that of the running water in the open culverts.

There were a good many foreigners in the vicinity, and a medley of languages filled the air. Many Persians were milling around, others sitting on the ground to sell their goods, mostly foodstuffs. The locals relied on the steady influx of these visitors, who sold important supplies of Persian specialities, particularly the much prized saffron. The market was also busy with Indians dressed in their salwar kamizes, Afghans in heavy coats and curly-moustachioed Iranians. There were as many types and styles of hat as there were people – the charawiya, the yashmak, the arakchinn, the keshida, the saydiya, the fina, the ’igal. There were even a few travellers from as far away as Rangoon. The horse-drawn tram had just made its final stop at Kazimiya station, which lay close to the shrine, and people were pouring out of the double-decker carriage, old women complaining loudly as they were jostled by young boys.

The shrine of Imam Musa al-Kazim and Imam Muhammad Jawad in Kazimiya was renowned for its two domes and four minarets.

In Kazimiya, the courtyard of the shrine was the first port of call for anyone wanting to find out the business of the day, from crop prices to political intrigues, to the state of the river. It was, therefore, an indispensable meeting place for any influential man in the town. As with the other shrine cities of Mesopotamia, there was a strong Persian influence in Kazimiya, and the beauty of the shrine owed much to the piety of the Iranian and Indian Shi’a, whose financial and artistic contributions had flowed into it through the ages. Unlike other Shi’a shrines in Mesopotamia, Kazimiya’s boasted four golden minarets on the outer side of the larger square complex that contained it, and two golden domes. They gave a dramatic dressing to the building, dominating the skyline.

The shrine housed the bodies of Imam Musa Ibn Ja’afar, the seventh Imam, and of his grandson Muhammad Jawad, the ninth Imam, who were direct descendants of the Prophet through his daughter Fatima. The seventh Imam had lived during the golden age of Baghdad, before being poisoned by the Caliph, Harun al-Rashid, the notorious figure mentioned in the Thousand and One Nights.

Abdul Hussein and Sattar entered the shrine through the silver-gilded main gate, the Bab al-Qibla, which opened onto a vast white square courtyard. Immediately they veered right under the arcaded, turquoise-and-yellow-tiled gallery. They were recognized by one of the many children who virtually lived at the shrine, and the boys dashed over to them, tugging at their robes. It was well known that Abdul Hussein always carried numihilu, lemon-flavoured sweets. He didn’t disappoint them, but reached deep into his pockets and gave each child a sweet. They tended to know better than his adult friends inside what the news of the day was, and they never hesitated to repeat what they had heard that morning.

In turn, Abdul Hussein took pleasure in gently scolding them. ‘You again? I thought I told you to go to school, ya razil, you rascal! What will loafing about here with your friends do for you when you grow up?’ He would hold up his hands in mock horror. ‘Yalla, don’t come back to me for a sweet if you don’t go to school!’ Part of him knew such chastisement was futile. These children had no compass in life. It wasn’t their fault – their parents were no better – and there weren’t enough schools in the locality to take on all these children.

Leaving the clamouring children in their wake, Abdul Hussein and Sattar crossed the courtyard. The shrine was half-empty. It was late morning, and the seminary students who occupied several of the alcoves in the arcade galleries were sitting, legs crossed, listening to their teachers. Their black and white turbans, indicating their lineage, or lack thereof, to the Prophet, moved up and down as they looked from their books to their teacher and back again.

Abdul Hussein’s friend the Kelidar, the shrine’s hereditary overseer, was standing with a group of men near the main entrance to the tomb room. Several old ladies in thin black abayas were seated nearby on the tiled floor. They leaned against the outer wall of the tomb room, chatting. Against the yellow brick, the patterned tiles shone turquoise, white and navy in the sun.

Before he could join the Kelidar Abdul Hussein felt his attention drawn to a well-dressed older man sitting alone in a corner, weeping. Puzzled by this distressing sight, he walked towards the man. ‘Assalamu alaikum – peace be upon you, my friend,’ he said courteously.

‘Wa alaikum assalam – and upon you,’ the man replied, brushing tears from his eyes with the heel of his hand.

‘Khair, what is the matter with you? Why are you crying?’

‘What can I tell you, ammi? Life has dealt me a cruel blow,’ the man said, pulling himself upright. He cleared his throat and explained: ‘God blessed me with a good fortune and I decided to divide it between my three sons. And now their mother has died and they don’t want to see me. I go to my eldest son and he barely offers me tea, the second one is always travelling and the third one is too scared of his wife, who doesn’t like me.’ He shook his head sadly. ‘I’ve always been a good Muslim, praying, fasting and giving alms – and I can’t believe this has happened to me. I’ve been left all alone. What kind of children are these?’ he asked in despair.

Abdul Hussein nodded gravely. ‘Don’t worry, my friend; there is a solution for everything.’ He promised to discuss the matter further with him once he had concluded his business with the Kelidar. Politely, he took his leave and crossed the courtyard.

‘Hadji, good that God brought you!’ the Kelidar exclaimed. The two men greeted each other warmly. ‘And how is the child?’ the Kelidar asked. Earlier that week Abdul Hussein’s son Hadi had given refuge to a little lost soul who had been haunting the shrine. The small boy had been found sitting in a corner of the shrine, crying and refusing all offers of help, even turning away a glass of water. But Hadi had broken through the boy’s misery, established that his name was Ni’mati, and offered him a place to stay under his father’s roof. Abdul Hussein assured the Kelidar that the child was settling in well.

‘That’s wonderful news, I can’t thank you enough!’ The Kelidar then proceeded to business. He explained that the town was organizing a welcoming committee to accept the gift of some new carpets which were arriving from Iran the following week, having been purchased through the Oudh Bequest. The result of a complex diplomatic agreement, the Oudh Bequest involved the political authorities of the Indian Raj and the Shi’a religious powers of Mesopotamia, and benefited the shrines in the region with regular improvements and maintenance. However, the mayor of Kazimiya had fallen out with the Nawab family, the Indian Shi’a notables who were in charge of administrating the bequest. One of them, Agha Muhammad Nawab, was Abdul Hussein’s brother-in-law, and the Kelidar hoped that Abdul Hussein could smooth the way for the ceremony.

For Abdul Hussein the request was a godsend; it meant that he could safely ignore the many other matters that the Kelidar hoped to raise with him, on the pretext of hastening to undertake this vital errand. He brushed his moustache with his thumb and index fingers, and said, ‘Zain – fine. I’ll undertake this without further delay.’ He excused himself and made his exit from the shrine, sending Sattar home ahead of him to prepare the landau for the short journey to the Nawab’s house. Following on Sattar’s heels as fast as he could, he huffed his way through the heat to the stables next to the house. ‘Bring me some water, quickly!’ he called out into the courtyard.

His son Hadi’s new friend, Ni’mati, came out carrying an engraved copper pitcher of water and a matching copper cup on a tray. Abdul Hussein smiled at the boy and rested his fez on one knee while he mopped the sweat from his brow. Then he drank deeply while his carriage was readied. Refreshed, he took his place on the left-hand side of the carriage seat. Accompanied by the steadfast Sattar, who never left his side outside the house, Abdul Hussein was soon on his way.

The palatial home of Agha Muhammad Nawab, Abdul Hussein’s brother-in-law, lay outside Kazimiya, south towards Baghdad. Abdul Hussein liked to take the picturesque route to it that ran closest to the river. There was one field in particular that he adored because of its wheat and reed sheafs, which stood nearly as tall as him. Their golden hue when the sun shone upon them was one of his favourite colours, and a momentary sadness always surfaced in him when the time came to cut them down.

The carriage drew up in front of the house and Abdul Hussein dismounted. Standing placidly in the waters of the rectangular pool was the new addition to the estate: a life-size stone statue of a deer. Abdul Hussein clapped his hands and repeated ‘Ayaba, ayaba’ in admiration as he walked back and forth around the pool, studying the stag from all angles.

Some of the garden staff and stable boys drifted over to watch, amused by his uncustomary excitement. They explained to him that the deer had arrived yesterday as a surprise gift for their master’s wife. Praising it, Abdul Hussein supposed that the Nawab had bought the statue to remind him of Hyderabad; there, deer hunting was a noble sport often portrayed in exquisite Mughal miniatures. In giving Munira the stag as a gift, the Nawab was also bringing a little of his home country to Baghdad.

A gardener told him that the stone deer had made the journey in a large wooden crate, travelling from Bombay to Basra by boat; then by steamer to Baghdad, with many stops along the way, until it had been conveyed by a small vessel to the jetty at the bottom of the Nawab’s garden, and finally installed in the middle of the pool.

The deer statue through the gates of the Deer Palace, circa 1925.

As absorbed as he was in the deer, Abdul Hussein was nevertheless looking forward to lunch, although not particularly to the company of his sister Munira, whose long face had tested his patience of late. Yet he hoped that she had prepared the food herself, as she sometimes did, because her culinary skills were superior to those of any of her servants. Her turshi pickles were legendary and, like a good bottle of wine, only improved the longer she kept them. Many years ago she had pickled an exceptionally fine batch of cucumbers, storing them in jars, one of which remained in Abdul Hussein’s pantry, where it was coveted by all.

When Abdul Hussein crossed the threshold he learned from a servant that the ageing Agha Muhammad Nawab was already taking his afternoon nap, recovering from his long trip. The dining room was empty, except for a servant girl who was laying out the dishes on the table. Munira was nowhere to be seen, but Abdul Hussein could hear her voice issuing faintly from the kitchen, where she was supervising some final touches. That was a good sign, he thought; she must have done the cooking.

As he sat down, Abdul Hussein automatically reached for the pickles, stuffing one into his mouth. He had barely begun crunching on it when his sister appeared and sat down in silence across the table from him.

Greeting her, he said, ‘What a wonderful deer the Nawab has brought for you! Your husband has really outdone himself this time!’

‘Yes,’ Munira replied dully. Her eyes with their deep shadows remained fixed on her hands.

Abdul Hussein held his plate out to be served another favourite dish: aromatic basmati rice infused with dried lime and saffron-flavoured chicken. He tried another tack. ‘Have you heard about the little boy Hadi found by the shrine, crying?’ Munira raised her head and glared across the steaming dishes at him. This time Abdul Hussein avoided her gaze.

He knew in his heart that she wouldn’t want to hear about children; that she blamed him for her childless marriage to the man she held responsible for their sister’s death. Their sister Burhan, the Nawab’s first wife, had been subjected to all the same rumours of barrenness and inadequacy that taunted her now. True, Abdul Hussein had thought that the match would be a good idea; the Nawab was a rich and influential man who could give Munira a good life. When Burhan had died and Munira had been married to him, nobody had known for certain that he wouldn’t be able to sire a family.

‘He doesn’t speak a word of Arabic,’ continued Abdul Hussein. ‘Probably from Hamadan or somewhere around there.’ When Munira sniffed unsympathetically, he snapped, ‘Not every fifteen-year-old would have done what Hadi did, and brought him home. You could at least be proud of your nephew!’

Munira glowered, but Abdul Hussein persevered: ‘Anyway, he seems to have taken well to the horses in the stables. We’ll sort him out. His name is Ni’mati.’

Munira leaned forward, her face covered with one hand, her elbow propped on the table-top. Abdul Hussein abandoned any further effort to enjoy his lunch. ‘What is wrong now, sister? Speak!’ he exclaimed. ‘You have everything you could possibly want – this palace, a respected and rich husband. A beautiful garden, that wonderful deer. All these servants … What on earth is wrong?’

‘This deer will be a curse,’ Munira said sullenly. ‘There has already been a crowd outside, staring at it. And they’ve started calling our house “the Deer Palace”.’

‘What rubbish!’ Abdul Hussein erupted. ‘Let the people talk – they talk anyway, and now at least they’ll have something pleasant to gossip about.’ He rose to his feet, threw his napkin on the table and curtly took his leave of her.

Munira remained in her seat. Her fingers clenched her water glass, which she suddenly hurled at the wall. She watched as the liquid dribbled down to the floor. The servants could clean up the broken shards later.

Abdul Hussein called for Sattar and the carriage driver, but they were nowhere to be found. He was so angry that he forgot to leave the Nawab a message about the important business of the shrine and the carpets. He tucked his fez under his arm, squashing it with the sheer force of his irritation, and started to march out of the garden, eyes fixed on the ground. Belatedly, he shouted back at a gardener, ‘Tell those imbeciles to follow me now!’

He crossed the grounds that faced the newly-named Deer Palace and walked down towards the riverbank, where he waved at a boatman to bring his guffa over. Guided by the expertise of such boatmen, round-bottomed guffas had been whirling their way down the Tigris for thousands of years. As the little boat transported Abdul Hussein towards Baghdad, the soft breeze calmed his heated temper a little. He could see boys flying homemade kites from the rooftops that lined the river. On the other side, he spotted one of the steamers of the British Lynch company heading south to Basra. It was time for his siesta, but he was still too agitated to rest.

A guffa on the Tigris in Baghdad, circa 1914.

He decided to cross to the eastern bank near the old city, where he could sit in one of the cafés near Maidan Square and smoke a nargilleh – a water pipe. Many cafés had sprung up there in the last few years, havens of music and liveliness, and Abdul Hussein was sure a visit to one would lighten his mood. But as the small boat neared the bank, he remembered the weeping old man back at the shrine, saddened by the behaviour of his three errant sons … An idea came to him, and he told the boatman to turn around and take him to the pontoon bridge at Kazimiya.

The pontoon bridge consisted of wooden boats tied together. As Abdul Hussein approached it, it gently rocked from side to side. Observed from a distance, the crowds of women in their black abayas who were crossing the bridge formed a single swaying mass.

Disembarking nearby, Abdul Hussein paid the boatman and made his way back home. There he found Sattar, and asked him to send one of the servants to fetch a builder and his tools. He ordered another member of his staff to find a huge metal cooking pot. The boy returned with the household’s largest pot, which could hold enough rice for fifty people. The boy must have thought his master had gone mad when he told him to fill it with soil and then cover it carefully so its contents were not visible.

Next, Abdul Hussein sent Sattar to visit the weeping man’s eldest son and invite him and his brothers to come to his house straight away. Surprised, the young men returned with Sattar to find the large covered pot waiting for them in Abdul Hussein’s courtyard. Abdul Hussein grinned at his guests and gestured to the pot: ‘Your father has left this pot and its contents with me in safekeeping for you. I’m instructed to give it to you once he has passed away.’

Presumably concluding that their father had even more money than they had imagined, the three brothers obediently followed Sattar and the other two servants into Abdul Hussein’s house. There, Abdul Hussein introduced them to the builder he had summoned, and explained, ‘I am going to store the pot here in this corner of my stables. This builder will construct a small box to cover it so that no one can tamper with the contents until it’s time. I want you to witness his work now.’

Some weeks later the old man came to visit Abdul Hussein, looking very much happier. ‘I don’t know what you’ve done,’ he exclaimed, ‘but my boys have come back to me! They’re completely changed, and now each one takes his turn to look after me. I’m so relieved.’

‘That is good news,’ Abdul Hussein said warmly. ‘I simply reminded them of the Holy Book’s recommendation that we care for our parents.’

‘Allah yikhalik – may God protect you. They seem to have heeded your advice. I don’t know how to thank you.’

Abdul Hussein smiled. He was quite sure those sons deserved the eventual disappointment of discovering that the pot was filled with mud. The important principle, as always, was that until then good order and harmonious relations be restored within the family.