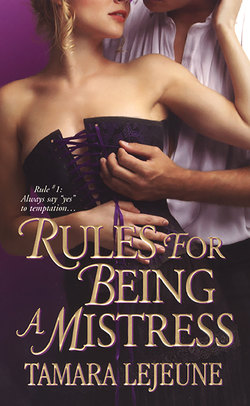

Читать книгу Rules For Being A Mistress - Tamara Lejeune - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1

ОглавлениеDespite all rumors to the contrary, Sir Benedict Wayborn had not been born with a cast-iron poker lodged up his bum. He simply had excellent posture. Even while traveling alone, as he was now, in a hired carriage miles away from his own county, the baronet sat up straight, as stiff and unyielding in private as he was in public. His face might have been carved from marble as he considered his lack of progress in securing a wife.

He was on his way to Bath. A hard rain continued to fall as night closed in, but Benedict ordered the coachman to drive on. From Chippenham they advanced at a snail’s pace until, about four miles from Bath, they stopped altogether. A vehicle was foundering in the road, its wheels lodged a foot deep in mud. As servants worked to move it, a gentleman and a young lady watched from beneath a single umbrella.

Having lost half of his right arm as a boy after being mauled by a dog, Benedict was never eager for the company of strangers, but he civilly instructed his driver to invite the Fitzwilliams to share his carriage for the rest of the journey.

Smelling strongly of cheap tobacco and French musk, the gentleman climbed into the carriage first. He scarcely looked old enough to be the uncle of the well-dressed young lady who jumped up after him, but that was his claim. Benedict kept his cynical suspicions to himself, and the carriage resumed its slow crawl toward Bath. The lady’s maid sat outside on the box with the driver, but the Fitzwilliams’ other servants were left to extract the gig from the mud.

Benedict had just begun to hope that his guests were as unsociable and taciturn as himself when the young man suddenly exclaimed, “Why, it’s Sir Benedict Wayborn! Forgive my silence, sir. I did not know you were anyone.”

If the baronet forgave, he did so silently.

“I daresay you don’t remember me; I’m Roger Fitzwilliam. My brother Henry is married to the Duke of Auckland’s sister. Now that your own charming sister is safely buckled to His Grace, you and I are brothers-in-law, are we not?” Having established this tenuous connection, Mr. Fitzwilliam ventured headlong into intimacy. “How is the dear duchess? Breeding, I trust?”

“I have not heard from my sister since she left England on her wedding trip,” Benedict replied, fumbling for his black silk handkerchief. He sneezed into it violently.

“Must you wear so much scent, Uncle?” hissed the young lady, embarrassed.

The Earl of Matlock’s daughter was a pretty girl of seventeen. Unfortunately, the purity of her skin was lost in the gloom, along with the brilliance of her dark eyes and the luster of her expertly curled chestnut hair. Her worst defect, however, was glaringly apparent: a wide space between her two front teeth. She looked as though she had not fared well in the boxing saloon.

“We waltzed together once at Almack’s, Sir Benedict, but you neglected to call on me the next day,” Rose accused. “All my other partners called in person, except my Lord Redfylde, but he at least sent tulips—and he is a marquess!”

Try as he might, Benedict could not remember dancing with her. She was just the sort of insipid, yet insufferably vain, debutante that had forced him to abandon London.

“Don’t annoy the gentleman,” Fitzwilliam admonished his niece. “As I was saying: what a good thing you were passing, Sir Benedict. We actually sank in the mud, by Jove! I blame Rose: five enormous trunks full of frills and furbelows!”

“It would be a very strange thing if I had fewer than five trunks,” Rose protested. “You men may wear the same thing three days running if it pleases you, but a lady must change her dress at least three times a day, and she must never be seen wearing the same thing twice.”

“Poor Rose! Only seven hundred pounds a year on clothes. How do you survive?”

Rose did not choose to respond to her uncle’s impertinence.

“I daresay we will have less competition in Bath,” Fitzwilliam went on. “Eh, Sir Benedict? Little Bath is not so crowded as mighty London. Cheaper, too, if that matters to you.”

Benedict merely eyed him with chilling scorn.

“I did not get on at all,” Fitzwilliam complained. “London ladies all think themselves too smart to be vicars’ wives, I can tell you! If the Marquess of Redfylde would only make up his mind, we poor bachelors might get on, but, as it is, all the girls have set their caps at him.”

“We are not all mercenary, Uncle,” Rose said hotly.

Fitzwilliam’s smile was pained. “You must understand, Sir Benedict, that my niece’s season has been scrapped for a complete disaster. I am conducting her to her mama in disgrace. Lady Matlock will be able to puff her off in Bath, I daresay. The place is full of gouty old men on the lookout for something young and warm. Present company excluded, of course, Sir Benedict,” he added unctuously as Rose fought back sudden tears.

Fitzwilliam patted her hand. “There, there, pet. It was not your fault Westlands did not propose. You did everything you could. What did his lordship mean, taking her out driving in the park every day, waltzing with her at Almack’s, and then haring off to Derbyshire without proposing?” he demanded, apparently of Benedict. “You know Westlands, of course, Sir Benedict: Lord Wayborn’s son. Why, you must be cousins.”

“The connection is very distant, I assure you,” Benedict said coolly.

“She might have had Redfylde himself, poor child, if Lord Westlands’s attentions had not been so marked. She might as well be used goods! I’ve a mind to call him out, the rascal.”

Rose said maliciously, “You forget, Uncle, that Westlands is an excellent shot.”

“So am I an excellent shot!” cried Fitzwilliam, and the pair fell to arguing over which gentleman would most likely be killed in the hypothetical duel: the viscount or the vicar.

Benedict took the opportunity to blow his nose. Perhaps it was selfish, but he did not care if Lady Rose Fitzwilliam died an old maid. He did not care if his distant cousin Lord Westlands had behaved like a cad. He did not care if Westlands and Fitzwilliam killed one another in a pointless duel. He wished he could set the Fitzwilliams down in the road and leave them to their fate, but, sadly, one was bound by a code of civility.

He pretended to fall asleep. Fitzwilliam soon slept in earnest, but Rose, bored, drummed on her jewel box with her gloved fingertips. “You can stop pretending now, Sir Benedict,” she said, pouncing onto the seat next to him. “We must have some conversation, or I shall go mad!”

He opened his eyes. “Kindly return to your seat, Lady Rose.”

“You’re only number fifty-six on my aunt’s list of eligible bachelors,” she sniffed angrily. “Aunt Maria says you’re too stuffy and dignified to run after girls half your age, but I’ve noticed that you dye your hair black in an effort to appear younger.”

Benedict could not be goaded so easily. He simply closed his eyes again. To his relief, Rose returned to her seat and did not speak again until they reached her mother’s house in the Royal Crescent of Bath, and there she only thanked him haughtily as she quit his carriage.

Lord Matlock had not joined his countess in Bath. Therefore, his lordship’s youngest brother was obliged to put up in the York House Hotel in George Street. Fitzwilliam jumped out into the hotel yard, grumbling about the expense, and releasing such potent waves of French musk that Benedict was obliged to step out of the carriage until he stopped sneezing. Reluctant to return to the noisome, confined space, the baronet paid the coachman and dismissed him.

The house he had leased from Lord Skeldings stood at a distance from York House, but Benedict had strong legs and an excellent umbrella. For sixpence a boy from the hotel agreed to carry his valise. Declining both Fitzwilliam’s offer of a late supper, and the landlord’s offer of a sedan chair, he gave the boy the address, and they set off on foot. The rain, which had almost stopped, seemed to pick up again as they climbed up Lansdown Road to Camden Place.

By no means as famed as the Royal Crescent or the Circus, Camden Place was still one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in Bath. Benedict had chosen it for its remoteness. The long, steep walk up Lansdown Road did not trouble him in the least. He liked to walk.

On a night like this, Benedict’s valet would usually greet his master at the door with a hot brandy, but, oddly, there was no sign of Pickering as they walked up to No. 6 Camden Place. More puzzled than annoyed by his manservant’s absence, Benedict paid the boy from the hotel his sixpence and rang the bell. When no one answered, Benedict became concerned.

He could not possibly have guessed that the storm had played a cruel trick on him. This was not No. 6 at all. It was No. 9. The violent storm had pulled the brass number loose at the top, spinning it around and around until it finally came to rest upside down. Pickering was waiting up for his master across the street. In fact, had it not been for the long, narrow park that ran down the middle of Camden Place, Pickering would have been able to see his master from where he stood looking out of the window, and Benedict would have been able to see him.

Benedict took out the key that his landlord, Lord Skeldings, had given him. His handicap obliged him to close his umbrella and wedge it between his knees first, which made it a wet and awkward operation. To make matters worse, a sudden gust of wind sheered his hat from his head and tossed it over the iron railings of the park. Benedict scarcely noticed the loss, having just discovered a greater calamity: his latchkey did not fit.

“Perfect!” he muttered. Now he was annoyed. Cursing under his breath, he began to bang on the door with his umbrella.

Miss Cosy Vaughn gasped as her naked feet slapped the floor of her bedroom. The bare floorboards were so cold that, for a moment, she forgot why she was getting out of bed in the middle of the night. A rhythmic banging from downstairs soon restored her memory, however: some nameless fool was pounding on the front door, and if she didn’t put a stop to it, the noise would wake up her mother, if it hadn’t already. Fumbling for the candle on her bedside table, she lit it, savoring its warmth as she pulled on her dressing gown.

There was no fire in her room because the coal was running out, and the collier, who could roast in the hot coals of hell for all she cared, had declined to extend the Vaughns any more credit. Cosy had gone to bed bundled in a shawl, with woolly socks on her feet. The socks had itched so badly that she had peeled them off in the dark, but now, still half asleep, she searched for them, her teeth chattering.

The windows of her bedroom faced the street, but with the rain coming down in sheets, she could see nothing when she looked through the dark glass. As the knocking continued, she hurried to check on her mother and sister, who were sharing a bed in the next room to conserve fuel. Warmed by “logs” painstakingly crafted from tightly rolled overdue bills, the room was blazing hot. Lady Agatha, propped in a sitting position so as not to disturb the cold cream on her pockmarked face, snored peacefully while nine-year-old Allegra had flung the bedclothes off and was hanging half out of her mother’s bed, her mop of pale, straight hair almost grazing the floor.

“Who is he at all, Miss Cosy? Sure he knocks like a bailiff.”

Nora Murphy had come down from the attic with a shawl thrown over her nightgown, scraping her wiry, grizzled hair into a bun as she hurried down the hall.

“A bailiff wouldn’t trouble himself in such weather,” Cosy shrewdly pointed out. “It must be a messenger,” she added, crossing herself in a quick prayer.

Nora’s beady eyes bulged in terror. “Is it our Dan?”

Dan was Cosy’s brother. Lieutenant Dante Vaughn had recently sailed out of Tilbury on his way to join their father, Colonel Vaughn, who was stationed with his regiment in India.

Fearing everything from shipwreck to cannibals, Cosy ran back to her own room with Nora at her heels. Opening the window, Cosy leaned out. Rain blurred her vision, but she could just make out the shape of a man. “He’s left-handed,” she reported, having absorbed in childhood the Irish superstition that left-handed people are an unlucky breed.

“A ciotog,” Nora cried, crossing herself. “Sure the left-handed are the Devil’s own.”

Ashamed that she had yielded even briefly to a silly old superstition, Cosy pushed her head out of the window again. “What is your message, sir?” she called down, shouting over the roar of the streaming gutters. Her voice was instantly carried off by the wind, and she was obliged to scream at the top of her voice: “WHAT DO YOU WANT?”

Benedict had rented a house complete with staff. “Let me in!” he roared, incensed that one he took for a servant was not already downstairs waiting on him hand and foot.

“WHAT?” Cosy shrieked, shielding her face from the rain with one arm.

“LET ME IN. I AM SIR BENEDICT. I’VE BEEN GIVEN THE WRONG KEY.”

“It’s not a messenger, thanks be to God!” said Cosy, pulling her head in out of the rain. “He says he’s Sir Benedict. He’s locked out of his house, poor man.”

“I don’t care if it’s Saint Benedict he is,” Nora declared stoutly. “You can’t be letting in strange men in the middle of the night, Miss Cosy. You’re not in Ireland anymore.”

Cosy stuck her head back out and howled, “I’LL COME DOWN.”

“You’re too kind,” Benedict muttered, shivering, as she slammed the window shut.

Wet to the waist, Cosy ran to her wardrobe and opened the doors, her teeth chattering. “You’d not want to be left out in the rain yourself, Nora Murphy,” she snapped in response to Nora’s silent disapproval. “I daresay none of his English neighbors would let him in.”

“I’ll wake Jackson,” said Nora, naming the only other servant in the house.

“You will not,” Cosy said, toweling her hair into a damp, tangled mess. “He’s stocious, and I’ll not have Sir Benedict thinking all Irishmen are drunkards! Go and let his lordship in while I get dressed.” She threw off her dressing gown and pawed through the clothes in the wardrobe in search of something warm and modest to put on.

“I’ll not be seen by an Englishman in me shift,” Nora declared, shocked. “And a ciotog on top of it! He’ll be apt to make an atrocity out of me. You’d better go yourself, Miss Cosy.”

Cosy gurgled with laughter. “Ha! And be made an atrocity of?”

“Sure they never interfere with the gentlewomen,” Nora explained, pulling her shawl tightly around her crooked, spare body. “But he’d ravish me quick enough, and I am only a servant.”

Cosy grabbed an old riding skirt and pulled it on over her nightgown. The nightgown was of the finest French silk, but the skirt was of cheap green baize, the felt-like material used to cover gaming tables. Hardly fashionable; she usually wore it with a matching jacket when she cleaned house. “Let him in, you old wagon,” she insisted, hastily tucking her nightgown inside the skirt, “or I’ll tell Father Mallone of your un-Christianlike behavior!”

The threat had its effect on Nora. “I will, Miss Cosy,” she intoned in her sepulchral voice, her ropy limbs taut with offended dignity. “But when the ciotog murders us all, don’t come crying to me.”

Nora swept out, leaving her young lady to finish dressing in the dark. Downstairs, she opened the door so suddenly that she almost received a rap on the nose from the gentleman’s umbrella. “Good evening,” he said with crushing dignity. “How awfully kind of you to let me in. I do hope it wasn’t too much trouble.”

He held out his umbrella to the little hunchback, but, to his astonishment, she let out a shriek and ran away. “Sure Miss Cosy will be down in a squeeze, your honor!” she squeaked as she ran. “’Tis only after jumping into her clothes she is!”

She took the candle with her.

Presumably, “Miss Cosy” was the housekeeper, probably the woman who had shouted at him from the window. Benedict disliked her already. Needless to say, he was not accustomed to being kept waiting in a cold, dark hall while the housekeeper jumped into her clothes. And why was she a Miss Cosy, anyway? Married or not, most housekeepers assumed the honorific of “Mrs.” when they achieved the rank of an upper servant. Obviously, Miss Cosy wanted every man she met to think of her as marriageable!

After pushing his valise inside the house with his foot, the baronet closed the door against the wind and the rain and wiped his wet face with his sleeve.

Where the devil was Pickering? he thought angrily.

Since losing his right hand, he had learned to do everything with his left. Taking out his silver cheroot case, he lit a match, striking it on the underside of the hall table. After lighting the candles in a nearby sconce, he was able to see his surroundings a little better. The damask-covered walls and gilded sconces were in keeping with the elegance one expected from a Camden Place address, but the cheap tallow candles in the sconces cast a dirty, orange stain over everything. Benedict preferred the clean, white light of beeswax, a fact well-known to Pickering. Seriously displeased, he placed his umbrella in the stand just as a figure in skirts appeared at the top of the stairs. “Ah. Miss Cosy, I presume?”

Her Christian name was Cosima, but, as no one but her mother had ever called her that in her life, she saw nothing odd in this form of address. “Aye,” she answered, coming down the steps. “You said you were given the wrong key, Sir Benedict? You’re locked out?”

Miss Cosy was Irish, but, although she was obviously more genteel than the other servant, she made no attempt to speak with an English accent. “I rang the bell,” he complained.

“Ah, sure, we disconnected that jangly old bell,” she explained cheerfully.

“Indeed! Help me out of my coat,” he commanded brusquely, putting his back to her. As he turned, Cosy caught sight of his right side. His right arm ended abruptly at the elbow, and his coat sleeve had been pinned up. Poor man! He really was a ciotog. He must be a war hero, thought the colonel’s daughter, instantly claiming the stranger for the Army.

“I will, sir,” she said in a tone of great respect. Descending on him in a rush, she peeled the fine black wool from his shoulders. Wet through, the fabric stank of tobacco and perfume, which could only remind her of her own father, except that, being an incorrigible drunkard as well as a remorseless philanderer, Colonel Vaughn usually stank of whiskey, too. “I’ll hang it to dry in the kitchen, Sir Benedict,” she offered courteously.

“Certainly not,” he said harshly. “I won’t have my coat smelling of cooking.”

Cosy thought the smell of her cooking would have improved his musky coat, but she held her tongue. “I’ll hang it here so,” she said cheerfully, finding a hook for it above his umbrella.

“You will give my coat to Pickering, of course. Where in damnation is he, anyway?” Reserved with his own class, the baronet gave his irritation full reign with her. “I sent him ahead of me. I hate being looked after by strangers. This is an unforgivable lapse.”

A sheltered young lady might have been shocked and intimidated by his anger, but Cosy was used to the rough ways of fighting men. Her father and brothers all drank and smoked and swore routinely in her presence. Compared to them, Sir Benedict was the consummate gentleman. She went to the table and fumbled in the drawer for matches. “That’s the trouble with sending a man ahead of you,” she said in her creamy Irish voice. “Sure they don’t always wait for you to catch up.”

Benedict preferred to be served in silent awe by his subordinates. “I sent my valet ahead of me to Bath with my baggage,” he explained coldly and ponderously, as if addressing an idiot. “I take it he has not yet arrived in Camden Place. He must have been delayed by the weather.”

Miss Cosy’s cheekiness was not quelled in the least. “You weren’t delayed yourself,” she pointed out as she lit the three candles in a branched candlestick. “If he left before you, and he’s going at the same rate, I’d say your man is in Bristol this night.”

She held the candlestick up and, for the first time, he saw her face.

His worst fear was confirmed in spades. Miss Cosy was a stunning beauty. How men must fawn over you, he thought. In the dull, orange light he could not tell the true color of her eyes or hair, but there was no denying that satiny smooth skin, that heart-shaped face, that cupid’s bow mouth. True, her nose was a trifle short, but this only served to take the edge off a beauty that might otherwise have been intimidating.

Benedict searched in vain for some other flaw that might give him a disgust for her. Her impertinent little chin had a hint of a cleft in it, but he liked that. Her breasts were small, but, unfortunately, he had always preferred females with light, youthful figures, while at the same time deploring the light, youthful minds that usually went with such females. In desperation, he noted that her hair was a tangled mess, carroty in the candlelight, but who knew what color in the sunlight; her clothes were ugly, cheap, and wrinkled and she looked like an unmade bed.

Ah, bed…What would it be like to share the bed of a beautiful young woman? To kiss that plump, saucy, little mouth, to feel those long silken legs wrapped around one’s waist, and to hear that soft, creamy voice sighing exquisite nothings in one’s ear?

One was appalled by one’s thoughts. One savagely set them aside.

Housekeeper, my arse, he thought. She looks more like a homewrecker.

Miss Cosy, if that was her real name, would have to be dismissed, of course. His sole purpose in coming to Bath was to make a respectable marriage. There could be no convincing the rude minds of the polite world that the ravishing Miss Cosy was not warming his bed as well as ordering his coal, and the inevitable gossip could only have a dampening effect on his marital aspirations, to say the least.

She would have to go, but how the devil was he supposed to get rid of her? Technically, she was Lord Skeldings’s servant, and his lordship now lived in London.

During this prolonged scrutiny, Cosy had been staring at him with ever-widening eyes. Finally, it was too much. “I’m sorry, sir,” she cried, fighting back a disrespectful giggle. “But your hair tonic is running down your face in black bars. You look like you’re in gaol.”

Humiliated, Benedict allowed her to lead him to the cupboard under the stairs.

When he came out with a clean face and neatly combed black hair, Cosy was pleasantly surprised. He was younger and better looking than she had expected. Naturally, she would have preferred a younger man with a spectacular physique, but he was taller than herself in an age when few men were. ’Tis always easier, she thought forgivingly, to fatten a man up than it is to slim him down. She didn’t mind the scars on his right cheek at all and the cold, penetrating unfriendliness of his light gray eyes actually sent a pleasurable shiver down her spine. Of course! He was a battle-hardened officer. Her pulse quickened as she imagined him, gray-eyed and black-haired, mounted on a white steed, in the midst of an internecine battle, issuing his commands no one would dare disobey with cold, ruthless precision.

She had fetched his valise while he was in the cupboard washing up.

“Is there no manservant to take my bag?” he inquired angrily.

She looked surprised. Evidently, men were supposed to take one look at her and turn into spineless jellies. That most men probably did just that was completely beside the point.

“There’s Jackson,” she answered, “but I gave him leave to attend a funeral this morning, and the result is, he’s no use to anyone tonight. It’s nice and warm in the kitchen, though, if you’ll follow me.”

“No, indeed! Be good enough to light a fire in the drawing-room.” Benedict brushed past her toward the stairs. Startled, Cosy dropped his bag and caught at his arm without thinking, taking hold of his empty right sleeve. Instantly, he pulled away from her, and, instantly, she released his sleeve.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” she stammered, truly horrified. “I meant no offense. There’s not enough coal for a fire in the drawing-room, I’m sorry to say.”

“Nonsense, Miss Cosy,” he said sharply. “I’m a member of Parliament. If there were a shortage of coal, I would have heard of it.”

It occurred to her that his severity might be masking a dry sense of humor. “I didn’t think to report it to the government, sir,” she said. “I didn’t think Lord Liverpool would be interested in the state of my coal scuttle,” she added, naming the prime minister.

Miss Cosy would have few options when she lost her position here, he was thinking. She belonged to the class meant to scurry about in the background, silent and invisible. She could never be invisible, not with that outlandishly lovely face. No sensible lady would hire her, and, if a gentleman lost his head and did so, the result would be only misery and disgrace, for what man could resist the constant temptation of sharing a house with such a beauty?

It would be wrong to dismiss her simply because she was young and beautiful.

And yet, she could not remain under his roof because she was young and beautiful.

Only one reasonable solution to this ethical dilemma presented itself. He could, of course, move her to a furnished apartment in London in the usual way, thereby averting any hint of scandal here in Bath. A charming mistress could only be an asset to him in his political career. In fact, if he meant to get on in politics, a charming mistress would be quite as necessary to him as a dull, respectable wife.

“You mean you failed to order enough coal,” he said aloud.

“I suppose I did bungle it,” she said. “I’m used to the turf we have at home, you see.”

“Home?” he repeated absently. “Oh, yes, of course; you’re Irish.”

“Don’t worry, sir,” she told him impishly. “I haven’t come to blow up Parliament.”

“I am glad to hear it,” he replied without a trace of humor.

Cosy gave him up as a lost cause. On the battlefield, he might well be a hero, but as a ladies’ man, he was a pure failure. “Will you come down to the kitchen, sir? It’s where the cat sleeps,” she added persuasively. “So you know it’s nice and warm.”

She started down the hall with his bag in one hand, the candlestick in the other.

As he followed her, Benedict could not help observing that her undergarments were of very fine silk, in marked contrast to the cheap baize of her skirt and jacket. He was able to make this observation because the back of her skirt had been tucked into its waistband. Giving her the benefit of the doubt, he chose to believe this had happened accidentally, no doubt while she was jumping into her clothes. Rather than call the faux pas to her attention, which would have embarrassed them both, he reached out and corrected the problem with a sharp, decisive tug.

Cosy whirled around. “What do you think you’re doing?” she demanded.

Benedict showed her only boredom and a slight, puzzled frown. “I beg your pardon?”

His unruffled calm succeeded in confusing her. “I thought—I thought I felt something brushing against me,” she said uncertainly.

“Oh? I daresay it was a draft.”

Evidently judging it best to keep an eye on him, she backed through the swinging door that led into the servants’ part of the house. After a short flight of stairs leading down, Benedict found himself, for the first time in his life, standing in a kitchen.