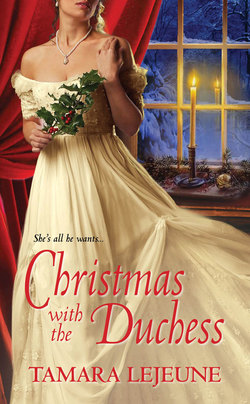

Читать книгу Christmas With The Duchess - Tamara Lejeune - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеSunday, December 11, 1814

Nicholas St. Austell sat in the swaying carriage, squeezed between Lord Hugh and Lady Anne Fitzroy, while five young ladies, daughters of Lord Hugh and Lady Anne, sat packed together on the opposite seat. Wearing a brown George wig and a greatcoat with half a dozen capes, Lord Hugh looked the prosperous, well-fed gentleman. His wife, by comparison, was a thin, faded lady with frightened, watery blue eyes. More often than not, she seemed bewildered by the world around her. They were as unlikely a couple, Nicholas supposed, as the brilliantly colored peacock and his lackluster peahen.

Until very recently, the young naval officer had not been aware of the existence of the Fitzroys at all, but now he was to understand that Lord Hugh and Lady Anne were his uncle and aunt—the lady being the elder sister of Nicholas’s dead father—and the five young ladies, whom he could scarcely tell apart, were his cousins. Together, they comprised all the family he had in the world, or so they claimed.

All seven of these Fitzroys had been waiting for him on the dock at Plymouth on the day his ship arrived in the harbor. They had been searching the world over for him, they said, and they seemed genuinely delighted to have found him, safe and sound, aboard the H.M.S. Gorgon. Before Nicholas quite knew what was happening, his aunt and uncle had claimed him, and he was in a carriage on his way to someplace called Warwick Palace.

It felt like he was being kidnapped. They are my family, he often had to remind himself. They are not kidnaping me. They simply are taking me home with them for Christmas.

Their delight in him continued unabated, but two days of travel had been more than enough to weary Nicholas of his companions. Lord Hugh—or Uncle Hugh, as he demanded to be called—had quickly revealed himself as a blustering bully. He shouted and snarled at his wife and daughters continuously, while Nicholas never received anything but smiles and platitudes from the man. As for the young ladies, they seemed to do little more than preen and giggle. Nicholas did his best to ignore them, but he was sure that their inane giggling would haunt his dreams for years to come. Lady Anne—Aunt Anne—was the only one among them for whom Nicholas had any feelings, and her he merely pitied.

As darkness fell around them on the third day, the carriage fell silent. Lord Hugh’s head fell onto Nicholas’s shoulder, and he began to snore, eliciting sleepy giggles from some one or other of his daughters. Suddenly, the carriage ground to a halt. Lord Hugh was pitched forward, his wig falling into Nicholas’s lap. Cursing, Lord Hugh let down the window and barked at the driver.

“We are at the gates,” Lord Hugh announced presently, closing the window against the cold night air. “Thank you, Nephew,” he added gruffly as Nicholas passed him his wig. “We will be at the house in two shakes,” he went on, clapping the hairpiece to his skull. “I’ve sent word ahead to my sister, and the keepers are holding the dogs.”

“If we had not stopped to help those stranded people, we would be there now,” one of the girls said resentfully. “I’ve missed my dinner!”

“We have all missed dinner,” one of the older girls told her sharply.

“A broken axle on a lonely road is no joke,” Nicholas said, nettled by the girls’ lack of charity. “It was our Christian duty to help the vicar and his wife.”

“Oh, someone else would have come along to help them,” said Lord Hugh. “I suppose at sea one is obliged to help all sorts of people clinging to shipwreck and all that sort of thing, but it’s really not necessary in a civilized country. You’re not in the Royal Navy anymore, you know.”

“But, sir, the lady was with child!” Nicholas protested.

“Shameless the way these clergyman breed,” said Lord Hugh, shaking his head. “Ah, well! What’s done is done. We’ll be in our beds soon enough.”

“I’m so tired! I’m cold! I’m hungry!” the girls complained.

“Then you should have eaten the sandwiches that were offered you,” Nicholas told them curtly. “And I can’t imagine why you’d be tired,” he went on angrily. “You’ve done nothing but sleep and giggle for three days. If there’s any work to be done, you fob it off on your mama.”

Lady Anne’s hand crept to touch his arm. “Do forgive them, Nicholas,” she pleaded. “They’re just tired and cross, that’s all. They don’t mean to complain. There’s no complaining in the Royal Navy, I’m sure,” she added.

Nicholas instantly felt ashamed. In the navy, malcontents routinely were flogged, but, he realized, young ladies ought not to be treated so harshly. “It is I who am cross, Aunt Anne,” he said contritely. “Forgive me, ladies. I am not used to traveling in a closed carriage. I am used to the open seas. I am used to dealing with men. I’m afraid my temper got the better of me. I apologize.”

“We forgive you, Cousin Nicholas,” they said in unison, reminding him, rather horribly of the verse from the Gospel of Mark: “My name is Legion, for we are many.”

“You see, Nicholas?” said Lady Anne. “They are good girls.”

“I hope we are not inconveniencing your sister too much, Lord Hugh,” said Nicholas, after a short pause. “It is very late. Why, it must be past midnight.”

“But Harriet is a spinster,” Lord Hugh said, dismissing Nicholas’s concerns.

The drive from the gate to the house was surprisingly long. From time to time, Nicholas caught glimpses of shadowy figures outside, men with broken guns moving in the torchlight, men holding back huge, vicious-looking mastiffs. Their breath hanging in visible clouds around their muzzles.

At last the carriage came to a stop.

A sleepy footman opened the door and let down the steps. Lord Hugh climbed out first. “This is not how I wanted to show Warwick to you,” he told Nicholas, as the young ladies left the carriage. “But you can get an idea of the size and the grandeur of the place. I will give you the grand tour tomorrow personally.”

Nicholas did not reply. Lady Anne remained in the carriage, and he was shocked to see how little her family respected her. Her daughters seemed to think no more of her than the carriage rug they had left lying on the seat. When he was not bullying her, her husband ignored her completely. Nicholas’s protective instincts were aroused. Climbing out of the carriage, he offered Lady Anne his arm.

The door was opened briefly to admit them. Nicholas guided his aunt into the hall. Two footmen were lighting candles, but the room still seemed vast and dark. The sharp, fresh scent of balsam hung in the cool air.

“There was no one outside to greet us, Sister,” Lord Hugh was complaining to a tall, elderly lady in a nightgown and lace cap.

“Everyone is asleep, Hugh,” Lady Harriet told her younger brother. “I was asleep.”

“A poor excuse!” said Hugh, sneezing. “What is that smell?” he demanded, sneezing again. “It stinks of the outdoors.”

“It’s balsam,” Nicholas said happily, “and holly. It’s all over the room. It smells like a forest. It smells like Christmas.”

Holding aloft a branch of candles, Lady Harriet looked at Nicholas curiously. He was a good-looking young man with brown skin and bright blue eyes. His features were strong and clear-cut. His sun-bleached hair grew in a good line. He wore it long, but tied back neatly in a queue.

Lord Hugh, meanwhile, glared around him, squinting into the dimly lit corners of the great hall. The beautiful wreaths and garlands ornamented with gilded fruits and velvet ribbon that had been hung about the room did not meet with his approval. “By God, you’re right! It does smell like a bloody forest in here. What is the meaning of this, Harriet?” he demanded, pulling a handkerchief from his pocket to block another sneeze. “Have you run mad in your old age? Are the servants conducting pagan rites in the small hours? Have all this damned shrubbery cleared off at once!”

“It was the duchess’s doing, not mine,” Lady Harriet replied evenly. “It is the custom in her mother’s native Germany. You will have to bring your complaint to her, I’m afraid.”

Lord Hugh grunted. “She’s here, is she? Good. I will deal with her tomorrow. In the meantime, clear this rubbish away. ’Tis pagan nonsense, and ’twas confined to the nursery when her husband was alive. I’m sorry you had to see this, Nicholas.”

“But I think it’s charming,” Nicholas protested.

Lord Hugh blinked at him. “You do?”

“Yes. It reminds me of the Christmases I had in Portsmouth when I was a child, when my parents were still alive. But, of course,” Nicholas added sheepishly, “our little cottage was nothing at all compared to this place, and we only had bits of holly and mistletoe. No balsam.”

“I suppose, if it does not offend you, it can stay,” Lord Hugh said reluctantly. Covering his nose and mouth with his handkerchief, he hurried upstairs.

Lady Harriet smiled at Nicholas. “I am Lady Harriet Fitzroy. You must be Lord Camford,” she said pleasantly, “the very fortunate young man who recently inherited the title and estates of Lady Anne’s brother.”

Nicholas blushed. “That is what everyone keeps telling me, ma’am,” he said. “I have yet to believe it.”

Lady Harriet’s eyebrows went up. “Indeed? But I read all about it in the London Times.”

Nicholas smiled. “In that case, it must be true.”

“I think we must accept that it is.”

Lord Hugh stopped at the top of the stairs to bellow at Lady Anne. “Madam wife! Take the girls up to their rooms at once. Octavia looks a fright, and Augusta is jumping up and down as though her bladder is fit to burst.”

“Oh!” cried Lady Anne. “But Nicholas—”

“Harriet will look after my nephew,” he told her. “Step lively, woman! How will you ever find husbands for these wretched girls if you let them go about looking like a pack of wet hens? What kind of mother are you?”

Lady Anne jumped. “Come, girls,” she cried breathlessly, hurrying her daughters from the room.

“Now, then,” said Lady Harriet, holding her candlestick up to get a better look at the young man in front of her. “Let’s have a look at you. My goodness! You are a beauty, aren’t you?”

Nicholas gaped at the old lady in astonishment.

“You must take after your mother,” she stated. “As a rule, the St. Austells are small, ugly, tedious creatures. But you’re like a big, bronzed Nordic god, aren’t you?”

“I—I don’t think so,” he said, blushing. “But thank you, ma’am.”

Her dark eyes twinkled at him. “Come, my lord, I will show you to your room.”

“I wish you would call me Nicholas,” he said. “I don’t feel like a lord. Any moment now, I feel like I’m going to wake up from a dream and find myself back in the navy,” he confessed.

Lady Harriet glanced back at him in surprise. “Since I am old enough to be your grandmother, I don’t see why not. And you may call me Aunt Harriet, if you like. That’s what the young people call me.”

Nicholas followed her through a maze of corridors to a large, beautifully appointed chamber. A cheerful fire crackled in the fireplace.

“Well, Nicholas! I hope you will be comfortable here in Westphalia,” Lady Harriet said. “It is not one of our best rooms, I’m sorry to say, but that is what happens when you are late. All the good rooms are taken.”

The young man looked at the huge, four-poster bed in amusement. “I was put to sea, ma’am, when I was but nine years old,” he told her.

“That explains it, then,” said Lady Harriet.

“Explains what, ma’am?”

“Why you seem to have absolutely no idea just how attractive you are,” said the old lady. “But, if you were put to sea when you were nine; if you have been in the company of men, for the most part, since that age, that would explain this strange case of modesty. Most young men with your good looks are vainglorious, insufferable peacocks.”

“I hope I am not a peacock,” said Nicholas. “I was going to say, ma’am, that, in the Royal Navy, we are used to sleeping in our own coffins. When one of us dies at sea, he is simply nailed inside his bed and lowered overboard into Davy Jones’s Locker.”

“Good God,” said Lady Harriet.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” he said quickly. “That is not fit conversation for delicate ladies.”

“I am not so delicate as I appear,” Lady Harriet said dryly. “If you would prefer to sleep in a coffin, we will, of course, have one brought in!”

“No, ma’am, I thank you. The room is more comfortable than any I have ever had the pleasure of seeing.”

“Did your valet arrive earlier in the day, my lord? I will try to find him.”

“Oh, we don’t have such things as valets in the Royal Navy,” he told her, chuckling. “I was not the captain, ma’am, merely a lowly lieutenant! And a second lieutenant at that. I can look after myself. I always have.”

Lady Harriet inclined her head. “In that case, my lord, I bid you good night.”

“Good night, Aunt Harriet.”

My God, they’ll eat him alive, Lady Harriet thought sadly as she left him. She had not expected him to be so nice.

Emma’s French maid roused her very early the next morning. Emma sat up, rubbing her eyes as Yvette fired streams of French at her.

“What?” Emma cried, jumping out of bed. “When?”

Pulling on her dressing gown, she ran to the door. Carstairs, the dignified old butler, stood there. “When did Lord Hugh arrive?” the duchess demanded.

“Very late last night, your grace. After everyone had gone to bed. My subordinates did not make me aware of it until this morning.”

“I’m sure they wanted to let you sleep, Carstairs. My sons were not with him, I understand.”

“No, your grace,” Carstairs answered in his funereal voice.

“You have not received any instructions regarding their arrival?” she asked hopefully.

“No, your grace. Lord Hugh has asked me to inform your grace that he will see you this afternoon at three o’clock in the Carolina Room—if he is not too busy. You are to wait for him there?”

Emma bit back a curse. “Is that so? Is there anything Lord Hugh desires?”

“No, your grace.”

“I’m afraid three o’clock is not convenient,” said Emma. “Where is Lord Hugh now?” she asked, forcing herself to speak calmly.

“He’s been placed in the Dresden Suite, your grace.”

Emma frowned. “And where the devil is that?” she wanted to know. The house was so large, and she visited it so seldom that she did not know all the rooms. “No, don’t bother trying to tell me. You’ll have to take me to him, Carstairs,” she said decisively. “The house is full of strangers. It would never do if I went to the wrong room.”

“No, your grace,” he agreed.

“Wait here while I get dressed.”

The duchess’s toilette usually took three quarters of an hour, but this morning her maid’s perfectionism had to be balanced with Emma’s desire to be done quickly. In the end, it took fifteen minutes, and neither woman was satisfied. The maid ran after her mistress, putting the finishing touches to Emma’s hair until she could keep up with the duchess’s pace no longer.

“Is he awake, do you know?” Emma asked Carstairs. “If he’s gone down to breakfast already, I shall miss him.”

“I do not know, your grace. I felt it best to come to you, directly. But it is not Lord Hugh’s habit to wake early.”

“He brings his sad little wife with him, of course, and all their daughters,” Emma murmured as she followed the butler through the house. “I’m surprised he didn’t invite all his friends, too! But, perhaps, he has no friends.”

“His lordship did bring one young man with him,” said Carstairs.

“Only one?” Emma snapped angrily. “But why should he not invite anyone he likes to my son’s house? This young man is attached to one of the girls, I suppose,” she sniffed. “Do we hear wedding bells, Carstairs?”

“The night footman informs me that the young man is Lady Anne’s nephew, your grace.”

“Anne’s nephew?” Emma repeated, frowning. “If Anne has got herself a nephew, why, he must be the new Earl of Camford! The one they’ve been looking for all these years.”

“Yes, your grace.”

Emma gave a short laugh. “I’d heard they were scouring the globe for some long-lost heir, but I had always assumed he was entirely fictitious. I suspect this young man is nothing more than an artful impostor. His discovery—just as the Crown was about to take possession—! well, it’s too convenient for belief. Has the Crown conceded?”

“There was an announcement in the Times of London some weeks ago. Your grace was in Paris.”

“Oh, I see,” Emma said, making a face. “It must be true, then. Well! Hugh and Anne must be delighted that Camford won’t be reverting to the Crown, after all.”

Carstairs prudently offered no comment.

“I wonder they do not spend Christmas at Camford,” Emma said after a moment. “But then again, why shouldn’t they entertain his lordship here instead, with little trouble and no expense to themselves? The earl must be a single man.”

“I believe so, your grace,” Carstairs replied evenly. “At least, his lordship does not bring his wife with him.”

“Of course he’s single. They would not bother with him if he were married already; he would be quite safe from the Miss Fitzroys. He will be expected to marry one of them, of course. I suppose he is to be pitied.”

Emma fell silent, mentally preparing herself for the coming interview with her husband’s uncle. She wondered if, in her battle with Hugh, Lord Camford could be an ally, or, at least, a useful tool.

As they passed through the long gallery that separated the east wing from the west wing, a young man suddenly stepped from behind one of the marble columns, stopping directly in Carstairs’s path. Emma looked at him curiously. She was sure she had never seen him before, but, then Warwick Palace was always full of strangers at this time of year. He was too brown to be a gentleman, she decided, and his ill-fitting clothes, she noted with some amusement, were of poor quality. His coat was so tight that it all but pinned his arms to his sides. Though he was tall, much taller than she, his shoulders were pulled forward by his tight coat, giving him a round back, and causing him to stoop a little. She didn’t like his long hair.

He looked distinctly out of place amid the incredible grandeur of Warwick, where even the servants were splendidly and immaculately dressed. He reminded her, oddly, of poor Cecily, who could never get it right, no matter how much she spent on clothes. Unlike Lady Harriet, Emma could not look past his flaws to see that he was actually quite good-looking. She did not see a bronzed Nordic god. She saw a scruffy-looking, badly dressed, overgrown boy.

“May I be of assistance to you, sir?” Carstairs said smoothly.

“Please! I’m completely lost, I’m afraid,” the young man confessed. “One needs a compass and a map in a place like this! Would you be so kind as to direct me to the breakfast parlor? I think it’s around here somewhere.”

“Which breakfast parlor would that be, sir?” Carstairs asked.

The young man’s eyes widened. “Which breakfast parlor?” he echoed in disbelief. “You have more than one, then?”

“Yes, sir,” Carstairs said gravely. “There are four: the summer breakfast parlor, the spring breakfast parlor, the autumn breakfast parlor; and the winter breakfast parlor.”

“Perhaps it would be simpler to ring for a footman,” Emma suggested, out of patience.

At the sound of her voice, the young man’s eyes flew to her face. He blushed, staring. His mouth did not hang open, but it might as well have. Emma guessed he could not be more than nineteen. She promptly dismissed him as a mooncalf.

“I beg your pardon, ma’am!” he exclaimed, stuttering and bowing. “I did not see you there.”

“Do you see me now, sir?” Emma asked him tartly.

“Oh, yes, ma’am!” he answered, shy and eager at the same time. Emma did not find his lack of sophistication refreshing. She could almost imagine that he had never lain with a woman before. He behaved almost as if he had never seen a woman before.

“Oh, excellent. What you want to do is find a bell and ring it,” Emma told him. “Do you think you can manage that, sir?”

“Yes, ma’am! Thank you, ma’am!” he said gratefully. “I don’t know why I didn’t think of that. I’m not used to servants, you see.”

Emma caught sight of a footman at the end of the hall. She beckoned to him, and he hurried over. “Would you be good enough to take this young man to the nearest breakfast parlor, with my compliments.”

“Yes, your grace. This way, my lord, if you please.”

Emma started in surprise. “Did you hear that, Carstairs?” she said in amazement, when the young man was out of earshot. “Arthur milorded him. Does he know something we don’t?”

Carstairs looked aggrieved. “He must be Lord Camford. Now that I think of it, he does meet the description.”

“What!” Emma exclaimed in astonishment. “That—that cub who gawped at me like a country bumpkin? That is the Earl of Camford? Where in God’s name did they find him?” she went on, beginning to laugh. “In a Hertfordshire hayrick?”

Carstairs was still suffering from the mortification of having incorrectly addressed a Peer of the Realm as “sir.” But he set aside his pain to answer the duchess.

“I understand his lordship was a lieutenant in the Royal Navy.”

“The navy?” Emma echoed in surprise. While the younger sons of the aristocracy routinely served as officers in the army, the navy was considered quite beneath them. Naval officers typically were drawn from the gentry. Emma laughed lightly. “Well, that explains it, I suppose! What a fine thing for the Miss Fitzroys!”

A short while later, Lord Hugh was shrieking in terror as Emma threw open the door to his bathing closet. Without his corset he was fat, and without his wig he was bald. Boiled pink by the hot water, he was not a pretty sight.

“Oh, good, you’re awake,” said Emma, in a tone of dire boredom.

“You!” he sputtered, his round, black eyes staring from his bald head. “How dare you! I am naked!” he cried. “Have you no shame?”

“Of course not,” Emma replied. “Don’t you read the gossip columns? Shame is exactly what I do not have.”

Lord Hugh’s heavy face turned almost purple. Veins stood out in his forehead. Quickly, he snatched the corners of the bathing sheet that lined the big copper tub, wrapping himself up like a package. All the while, he screamed for his manservant.

“Don’t worry, Uncle,” said Emma, as Lord Hugh’s valet came into the room, fluttering his hands ineffectively. “I did not come to gaze upon your crudites. You know why I’m here. I want to see my sons. Where are they?”

“Don’t just stand there, you idiot!” Hugh screeched at his valet. “Get this woman out of here! Throw her out, you imbecile!”

“Touch me, and I’ll have you killed,” Emma calmly told the valet, securing his immediate withdrawal. “Now then,” she said, turning back to Hugh with a wide smile. “You were just about to tell me where my children are.”

Lord Hugh sank down in the tub, scowling at her. “I do not have to tell you where they are,” he said petulantly. “There is nothing you can do. You are only a woman.”

“I am their mother!” Emma protested.

“But I am their guardian.”

“You stupid man!” said Emma, reduced by frustration to petty insults. “Where are they?”

He sniffed. She had caught him off guard, but he was back in control now. “I thought you were in Paris,” he said conversationally.

“I always come home for Christmas. You know that,” she said coldly.

“I could have saved you the trouble. Did you not get my letter? But I suppose,” he went on contemptuously, “you were much too busy entertaining your French lovers to bother about your children.”

“I received no letter,” Emma snapped. “And my children were perfectly safe and content at school, along with all the other children of the nobility. You took it upon yourself to interrupt their education, take them out of Harrow, and put them God knows where! Where did you put them? Are they even at a school?”

“If you had read my letter, madam, you would know where they were,” he told her. “You would also know that I have many debts of honor.”

Emma stared at him. “And why should I be interested in your gambling debts, sir?”

“Because you must pay them, of course,” he answered as if she were a simpleton.

“Indeed! Why is that?” she asked.

“Because I cannot pay them, and you are rich,” Lord Hugh explained, apparently amazed by Emma’s stupidity. “When he was alive, my nephew Warwick always paid my debts. I explained all this to you in my letter,” he added petulantly.

Emma controlled her temper with difficulty. “Even if my husband did pay your debts—which I do not believe—what has it to do with me?” she demanded. “I am no relation to you, except by marriage. Why should I pay your debts?”

He sighed. “In a perfect world, madam, your son would pay my debts. But his grace is still a minor. If I could borrow the money from the duke’s estate, I would, but these damned lawyers are very tightfisted. I can’t squeeze so much as a farthing out of them! Nay, madam, it will have to come from you. My debts are very pressing. Let me be blunt. If you do not pay my debts, you will not see your children. Is that simple enough for you to understand?”

“You expect me to pay to see my own children?” Emma said incredulously.

“Money is nothing to you,” he stated resentfully. “That German mother of yours left you millions, didn’t she? Seven thousand pounds would clear me entirely.”

“Then you must raise the money, sir,” she said coldly.

“I am a Fitzroy. We are descended of King Henry the Eighth. A Fitzroy does not go to Jews,” he said indignantly.

Emma laughed angrily. “No! He blackmails women, using their children as pawns!”

Hugh grew red in the face. “Will you pay or not, madam?” he snarled at her.

“No, I shan’t!” she said.

“Then you will not see your children,” he huffed, “if that matters to you.”

“You are bluffing,” Emma said confidently. “The war is over. Michael will be coming home any day now. He will expect to see his brother’s children. How will you explain to Lord Michael Fitzroy that you have kidnaped his nephews and are holding them for ransom?”

“There will be nothing to explain because you will pay me, madam,” he answered. “I came up with the plan myself. Therefore, it is bound to succeed.”

She scoffed at his sheer stupidity. “You would not dare prevent the Duke of Warwick and his brother from returning to their own home for Christmas. You would be reviled by everyone you know. You would be blackballed from your clubs. And, if it comes to it, do you think Lord Camford would marry the daughter of such a man?”

Lord Hugh started up in his bath, the color draining from his face. “What do you know of Camford?” he demanded, but his voice was hollow.

Emma saw at once that she had struck a nerve. “I know you would like him to marry one of your daughters,” she said, pressing her advantage. “When I expose your character, he will not be able to get away fast enough!”

“You speak to me of character?” he cried furiously. “Harlot! Jade! If my judgment is questioned, I will simply say that, as their guardian, it is my sacred duty to keep the boys away from the poisonous influence of their mother, a known wanton. Your beauty may blind others to the impurities of your own character, but I know all, madam. I know all about your little bastard, and the provisions you made for her.”

Shocked, Emma trembled, her face white. “What?” she gasped.

Seeing her tremble, Hugh smiled. “It was the one thing I did not bring out in court. When my poor nephew died so suddenly, I knew it was my duty to take his private papers into safekeeping. One doesn’t want such things to fall into the wrong hands, after all.”

“You have my letter,” Emma said dully.

He smiled. “I have your letter, madam. I always thought my nephew indulged you too much, but it is to his credit that he refused to let you pass your bastard off as one of his lawful children.”

“I will kill you,” Emma whispered, her nails digging deep into the palms of her hands.

He laughed harshly. “I have thought of that, madam. If anything happens to me, your letter will be made public. Your little bastard—what is her name? Althea? Athena? Attila? Unless you heed me, she will learn that her aunt is really her mother. Her little life will be ruined. As for your legitimate children, they will repudiate you, and despise you, too, if they don’t already. I could make your letter public now, of course, if that is what you prefer?”

Blind panic seized hold of Emma. She struggled to keep her head clear. “No,” she said, biting her lip. “Don’t. Please.”

The last word was forced from between frozen lips.

He smiled horribly. “Oh! You’re prepared to be reasonable then? Good. Pay my debts, and I will be reasonable, too. There is no need for your little Agatha to ever know the truth.”

Emma went rigid with contempt. Helpless hatred poured from her eyes. “You shall have a banknote for seven thousand pounds,” she said icily.

His fleshy lips curved in a grotesque smile. “Could you find it in your heart to make it ten thousand?” he asked. “One is always so strapped this time of year.”