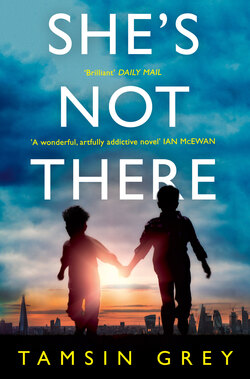

Читать книгу She’s Not There - Tamsin Grey - Страница 10

3

ОглавлениеThe car repair yard was silent, its gates padlocked, but there was that same oniony whiff from the warehouse. Same weather, of course, and the creature was moving again. Funny how, when it was asleep – and it was mostly asleep these days – he could forget it was there; that it had ever existed. He stopped at the bend in Wanless Road, setting his trumpet case down and wiping his palms on his trousers. Their house was still hidden from view, but he could see, across the road, the four shops. The Green Shop, the Betting Shop, the Knocking Shop, and London Kebabs. London Kebabs and the Betting Shop had their blinds down, and the Green Shop was all boarded up, but the Knocking Shop, on the face of it a hairdresser’s, looked open.

‘Why is it called the Knocking Shop, Mayo?’

‘Because of all Leonie’s visitors.’

‘But they don’t knock, they ring the buzzer, Mayo, so it should be the Buzzing Shop, shouldn’t it?’

She had laughed and kissed him, and he had beamed with pride. He had loved making her laugh. Standing there, looking at Leonie’s shop, he realised that the memory had brought the same grin to his fourteen-year-old face. He used to talk to her in his head when he wasn’t with her, he remembered; tell her jokes and see her laughing face. He picked up the case and walked on.

After five years, it was a huge amount to take in at once. First, there was a new building where the Broken House had been. Scaffolding still, and no windows, just the empty squares for them to go in. Running in front of it, a new fence, higher and more solid than the old one, with proper ‘Keep Out’ signs. A gap, and then the corner house, half on Wanless Road, half on Southway Street, the end of the Southway Street terrace; a strange, wedge-shaped house, which had once been a shop, and had been through many conversions. Their house.

Apart from it wasn’t their house. He stared, his eyes blurring. The same shape, and same size, but it had been all tidied and prettied, with pale blue walls and window boxes full of lavender.

Stupid idiot … He wiped his eyes on his sleeve. The house had sold very quickly, while he was still in hospital. It had been someone else’s house for five years. He walked round into Southway Street and looked at the shiny new front door, wanting to kneel and peer through the letter box. He turned away instead and looked up Wanless Road, towards the flats where his friend Harold had lived, and where he and Raff had had the run-in with the bigger boys. Then he looked back the way he had come. The passionflowers had survived, their gaudy, sulky faces tumbling over the new fence.

‘They look like Bad Granny.’ Raff’s six-year-old voice. He stepped forward and examined one in detail. Passiflora, a South American vine, named after the passion of Jesus Christ. He touched the crown of thorns, very lightly.

‘Jonah?’ A real voice, strident, familiar and – straightaway in his head, Raff again: ‘Let’s run!’ He gathered himself and turned. Her head was sticking out of the doorway. He gave a little wave, and she trailed out onto the pavement like a dilapidated peacock.

‘Hello, Leonie!’

‘Jonah! I knew it was you! Pat, look who’s here!’ She leant back into her shop, then turned, beckoning. He crossed the road and stopped with a bit of distance between them, but she stepped forward and took hold of his elbows, her bulgy eyes staring at him with a child’s frankness. Resisting the old urge to lift his good hand to cover the scarring, he tried to return her raking gaze. ‘Hench’. Raff’s word for her, because of her scary, weightlifter’s body, towering above them. Now, she only came up to his chin. Same brawniness, though; and same breasts, jostling to escape from their blue satin casing. He quickly looked back at her face. ‘Hello, Leonie,’ he repeated, aware of the awkwardness of his smile.

‘Mended good.’ The tang of her breath. Same hairstyle, with the beads on the braids, but fewer braids now and silvery threads in them. Same plastic, sequinned fingernails; she brushed one along the scarring. ‘Adds character. And you grown nice and tall. How long is it? Must be four, five years.’

‘It’s five.’

Leonie nodded. ‘Near enough to the day.’ She looked past him, at their old house. ‘What you doing here? This the first time you been back?’

‘Yes. I mean, I’ve been a few times, to visit friends, but not here …’ They’d never come this way, in the car; they’d always stayed on the main road and taken the turning by the park.

‘Pat!’ She called into the shop again, her ornate hand on the door. ‘She don’t hear me. You by yourself? Where’s your folks?’

‘I’m meeting them at our friends’ house. I came on the train, and they’re coming in the car.’

‘Pat! Where that dumb-arse woman got to.’ She shouldered the door wide open. ‘You better come in.’

He looked at his watch, hearing Raff’s voice echoing through time: ‘No way! She is HENCH and her sweets are RANK!’

‘Just five minutes. Have a cold drink. If she don’t get to see you, my life won’t be worth living.’ She ushered him over the threshold, and there was that same long, thin room with the mirrors, and the whir of the electric fans. Like his own ghost, he drifted behind her, past the three hairdressing chairs, and the one ancient hood-dryer; the desk, with the phone, and the box of tissues. The beaded doorway, the white, squishy sofa, the sweets in a bowl, and – an embarrassing stirring, Raff’s elbow in his ribs – the magazines.

‘Help yourself to a sweet.’

‘RANK!’

‘I’m OK, thanks.’

Leonie slammed the bowl back down, and kicked off her shoes. ‘Pat!’ She padded over to the beaded curtain, her big flat feet leaving damp marks on the polished tiles. ‘Losing her hearing. I keep telling her, but she won’t have it. You better take a seat.’

The fans whirred and whirred. The footprints evaporated, and the beaded strands shimmied to stillness. Above the doorway, the tiny monitor showed the litter-strewn backyard, where Leonie’s visitors waited to be let in. He got a sudden flash of her getting undressed, her blue satin dress dropping in a pile around her feet, and he cringed and tried to clear the thought from his head. He sat down on the sofa, which was as squishy as ever, but he was tall enough now to keep his feet on the ground. The magazines. Oh no. Remembering Raff’s shocked delight, he leant forward. The top one looked respectable enough – one of those TV guides – but the one underneath it … He stared for a moment, then put the TV guide back on top. Suddenly deeply uncomfortable, he looked towards the door. Too rude, though, to just leg it. He leant back, closing his eyes against the electric breeze.

‘The younger one was the looker. This one was always a bit drawn.’ Pat, trim little Pat, tufty-haired, fox-faced, with a jug and some plastic beakers. ‘World on his shoulders.’ She put the cordial and the beakers down, and perched next to him on the sofa. ‘Looks like life treating him better now.’ She grasped the lapel of his blazer and peered at the coat of arms on the breast pocket. ‘See, proper stitching – none of that stick-on.’

‘Private school.’ Leonie sank into the chair by the desk, and clasped her hands over her belly. ‘Folks doing OK, then.’

Jonah opened his mouth, then closed it again. Explaining about the scholarship would sound like boasting.

‘Cordial?’ Pat reached for the jug.

‘I’m OK, thanks.’

Pat looked at Leonie. ‘Must be thirsty, on a day like this?’

Leonie shrugged. ‘Maybe he don’t like cordial. Maybe too sweet for him.’

‘What about his hand?’

Leonie shrugged again. ‘Why you asking me?’

Jonah drew his bad hand out of his pocket, and presented it.

‘Your right one, is it?’ Pat took hold of it, and Leonie tipped forwards to look. ‘You right-handed?’

‘Yes, but it’s fine. I can do most things.’ He waggled his remaining finger and thumb.

‘Hope you don’t get teased for it.’ Pat set his hand down on his lap. ‘Do your school friends know how brave you were, trying to save your little brother?’

‘He don’t want to talk about that,’ snapped Leonie, and Pat clapped her hand over her mouth, chastened.

‘It’s OK,’ said Jonah. ‘Anyway,’ he nodded at the case, ‘I play the trumpet.’

‘The trumpet!’ Pat reached for the case and pulled it onto her lap. She opened it, and the trumpet nestled, gleaming, in the dark blue fur. ‘Play for us!’

Jonah hesitated. ‘I’m not sure if …’

‘Just one quick tune! Or you need a drink first? Will I get him plain water?’ Pat looked at Leonie again.

‘It’s just that the Martins are expecting me.’

‘The Martins. I remember them,’ Leonie was nodding. ‘With the little girl. Same age as you. Yellow tails, each side. So they still live round here? They never come this way. Or if they do, I never seen them.’

‘Her mother was sick,’ said Pat. ‘Must have passed by now.’

‘No, she’s better,’ said Jonah.

‘Better? I heard it was curtains.’ Leonie looked dubious.

‘Dora’s fine. She’s … we’re having roast chicken.’

‘Bit hot for roast chicken,’ said Pat. ‘Better with a salad, on a day like this.’

‘But nice you stayed friends with them,’ said Leonie.

‘What about the dad? Remember, Leonie – with the veg boxes. He still in that business?’

Jonah shook his head. ‘He lives in the country now. In an eco-village.’

‘Eco-village?’ asked Pat.

‘Living off the land,’ explained Leonie. ‘No electricity or nothing. Do their business in the woods.’

Pat shook her head. ‘So he left his sick wife.’

‘No, she was already better,’ said Jonah. ‘And anyway they’re still married. Dora and Em go and stay with him quite a lot.’

‘In the eco-village.’ Leonie nodded thoughtfully, as if she was planning a trip there herself. ‘And does he come back to London? Will he be there now? To see you?’

‘I expect so.’ He tried to remember if Dora’s email had said. Then he stood up, which was an effort, given how far he’d sunk into the sofa, and put his backpack on.

‘You got to go,’ Leonie sighed, and heaved herself up too.

‘Or roast chicken might get cold.’ Pat held out the trumpet case.

‘Yes.’ He suddenly felt how male he was, next to these middle-aged women: how tall, and strong and young. He took the case, and turned towards the door, trying to formulate a suitable goodbye, but was suddenly enveloped by Leonie. Her metal smell, her breasts, her damp armpits … He had to plant his feet firmly in order not to stagger back. She seemed to be crying. Still gripping the handle of his trumpet case, he put his free arm around her waist.

‘Leonie, she still feels so bad.’ Pat’s pointy face had gone soft and slack.

‘Bad? Why?’

‘Here all day, looking out the window, and never saw nothing was wrong.’ She patted Leonie’s shaking shoulder. ‘Enough now, Miss. Young man needs to go and eat roast chicken. And your 6.30 will be here. Need to bubble down.’

‘That 6.30 always late.’ But Leonie released him, and reached for a tissue from the box on the desk. She wiped her eyes, looking old, and Jonah felt a terrible tenderness for her.

‘Don’t feel bad. You were very good to us. Very kind.’ She was so alien, so not of his tribe – and yet so familiar. He patted her other shoulder.

‘Just glad …’ Her voice was shaky, still full of tears. ‘Just glad you doing so well.’

‘Better get going.’ Pat gave him a little push, but Jonah hesitated.

‘You know …’ He looked out into the sunny street and then down at his watch. The two women gazed at him. ‘Maybe I have got time to play something quick. If – if that’s what you’d like.’

‘Yes!’ Embarrassed by her own delight, Pat clapped her hand over her mouth again.