Читать книгу Things Thai - Tanistha Dansilp - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDecorative Arts

Items Created for Royalty and Wealthy Patrons

In what was until recently a highly structured society, the most skilled artists and craftsmen were requisitioned for work at the royal court, and a clear distinction existed between these specialists and those who worked in the villages. They were known as chang sib mu, meaning artisans of the ten types, and while they may have originally been drawn from the same pool of craftsmanship, their specializations were in courtly productions, including draughts-men and gilders (the first category), lacquerers, wax-modellers, fretworkers and fruit and vegetable carvers. To this day, a few have their ateliers within palace grounds.

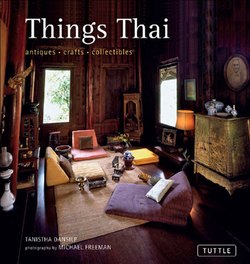

The interior of the Lacquer pavilion, a former scripture library, at Suan pakkard palace, Bangkok.

Lacquerware

khrueang kheun

One of the most important traditional crafts in Thailand, the manufacture of lacquer receptacles is heir to a long Asian tradition, of at least 3000 years, almost certainly originating in China. In its basic form, Thai lacquerware is undecorated and highly functional, although its inherent beauty may disguise its utilitarian nature. Well-applied lacquer has a remarkable range of characteristics, being light, flexible, waterproof and hard. It resists mildew and polishes to a smooth luster. Indeed, it has many of the qualities of some plastics, but with the advantage of being a naturally evolved product from local materials.

Lacquer in Southeast Asia comes from the resin of Melanorrhea usitata, a fairly large tree that grows wild, up to an elevation of around 3,000 feet (914.4 meters) in the drier forests of the north, and is similar to the sumac tree of China and Japan, Rhus vernicifera. It is completely unrelated, incidentally, to the shellac used in Europe and India, which is the secretion of an insect.

In Thai, lacquerware is called khrueang kheun (khrueang meaning in this case ‘works’), and this gives a clue to its origins. The Tai Kheun are an ethnic Tai group from the Shan States in Burma, and after the 1775 re-capture of Chiang Mai from the Burmese following a lengthy period of war, the new ruler, Chao Kawila, forcibly moved entire villages from Shan to re-populate and revitalize the city. This kind of re-settlement after victory was a common practice in the period, and craftsmen were particularly valued. One community, of lacquer workers, settled in the south of the city and their name became, for the Thais, synonymous with lacquer.

Although lacquer can be and often is applied to wood, its original, pure use was over a carefully made wicker base structure. This allows two of the finer qualities of the lacquer—its lightness and flexibility—to dominate. In fact, with a well-made bowl it should be possible to compress the rim so that the two opposite sides meet, without cracking or deforming it. The process is expectedly time-consuming. The form is first made using splints of hieh bamboo, and these must be of the width and thickness appropriate to the size of the object. If they are too big, the gaps between them will be too wide to take the coating of lacquer. The best time considered for applying lacquer is towards the end of the rainy season, when the atmosphere is moist but not too hot. The resin is applied in a number of layers, each of which must dry completely before receiving the next coat, and the entire process can take up to six months (very unlikely nowadays, of course!). The resin, known as rak in Thai, has varying admixtures at different stages. Often, the first layer has been mixed with finely ground clay to help it fill the gaps in the wicker-work, while the last and finest layers are mixed with ash, from burnt rice, bone or cow dung.

An 18th century English dresser complements a collection of northern thai flower-patterned red-and-black lacquerware.

A variety of black lacquerware boxes in shapes ranging from cylinders to carved frogs.

An offering receptacle lacquered red inside with gilding on black for the exterior; an oval box inset with diamond slices of bamboo; eight wooden nested bowls with mother-of-pearl rims.

Smoothing takes place once each layer is dry, again with a variety of materials according to the stage, including dried leaves, paddy husks and teak charcoal. Finally the finished piece is polished with oil. The natural color of the lacquer is black, and for the red finish that is characteristic of Shan-style lacquerware from the North, the coloring added is ground cinnabar for the best quality (now rare) or the less intense red ochre, which tends to flake.

And all this simply for plain lacquer! The oval box here has a rustic inlay of bamboo wedges in the shape of a flower, and the nested bowls have a decorative rim of mother-of-pearl but for the heights of decorative technique, practiced further south, in central Thailand for the court and major monuments, we have to look at gilded lacquer. Known as lai rod nam, the highly evolved technique of gilded black lacquer was a product of the capital cities, at its best in Ayutthaya from the 17th century to the middle of the 18th century, and later in Bangkok from the end of the 18th century. In Thai, this technique, which can justifiably be considered to have risen to an art, is called lai rod nam, meaning a ‘design washed with water.’ It refers to the stage at which the clear spaces in the design are removed, because the delicate nature of finely beaten gold leaf means that it cannot be applied directly as an intricate design, but must be combined with a resist—and it is this that is later washed off.

The starting point is the basic lacquer surface, polished to a perfect sheen. The design which will eventually be rendered in gold leaf is painted onto the surface with a resist, in the same way that batik patterns are created. The resist is known as horadarn ink, and is a sticky combination of makwid gum, sompoy solution and a mineral. As an aid to composition, it is usual to transfer the outline of the design first onto a sheet of paper. This is laid over the lacquer and the lines pricked gently with a needle to create a row of dots. A bag of ash or chalk is pressed over these dots and the paper carefully peeled away to leave a removable trace. The horadarn paint is then applied to the areas that will become the clear background—that is, the reverse of the image.

The whole area is then coated with a quick-drying lacquer resin, which is allowed to dry to the point of being sticky. Gold leaf is laid down over the entire surface. Then, after about 20 hours the work is gently washed with water; the composition of the horadarn ink is such that it absorbs the moisture and expands, pushing the gold leaf above it to become detached. This leaves behind the gold leaf applied to the lines and areas between the resist. Needless to say, the process did not always work perfectly the first time, and a considerable amount of retouching was often needed.

Some of the finest examples of Ayutthayan gilded lacquer work are on manuscript chests and cabinets, as were described under Religious Paraphernalia.

Ironically, while the technique of gilding lacquer came from China, it was Chinese art that was responsible for the decline of standards in Thailand. As Professor Silpa Bhilasri points out, the two conventions were incompatible, with Chinese gilded lacquer design treating spatial elements in a three-dimensional manner. Yet, during the early 19th century the popularity at court for things Chinese encouraged the introduction of this Chinese form of expression, to the detriment of the two-dimensional, complex space-filling Thai art.

Black lacquer boxes from northern thailand, inlaid with bamboo and bone, make cosmetic boxes for a dressing table.

Contemporary mother-of-pearl in the form of a mosaic inlay in black lacquer on curved serving plates.

A rattanakosin period polygonal stand inlaid with mother-of-pearl in Ban Mor, Bangkok.

Mother-of-Pearl Ware

khrueang muk

A craft that probably developed in Ayutthaya as early as the mid-14th century, and which the Thais practice in a distinctive style, is mother-of-pearl inlaid into black lacquer. It is painstaking work: the individual elements are very small and lacquer-embedding involves many applications. Yet the best Thai craftsmen have gone to extremes, not just of intricate detail, but of scale of the finished objects. The best-known examples, remarkable in their execution, are the doors of the ordination hall or ubosot at Wat Phra Kaeo, the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. From a distance they display a coherent decorative design, yet close up the decoration resolves into intricate miniature scenes; as the scale changes, so does the part played by the shifting nacreous colors. This is a hallmark of fine mother-of-pearl inlay.

The mother-of-pearl is the nacreous inner layer of the shell of some molluscs, including oysters. As with pearls, the luster is from the translucency of the thin lining, while the play of colors is caused by optical interference. Thai craftsmen favor the green turban shell found on the west coast of southern Thailand for the density of its accretions, but because the shell is naturally curved, it must be cut into small pieces in order to assemble into flat inlay work. Even then, the pieces must be ground and polished to flatten their edges. Working with large numbers of small pieces of shell inevitably complicates the assembly process, but it also stimulates the intricacy characteristic of inlay work.

The design is first traced onto paper. Next, the outer surface of the shell is removed by grinding, and the remaining mother-of-pearl sections are cut into pieces generally no longer than 1 in (2.5 cm). These pieces are honed with flint or a whetstone to reveal the color, and then temporarily glued to a wood backing or a V-shaped wood mount, ready for final cutting. The design is transferred to the shell by tracing paper, which is then cut into individual pieces with a curved bow saw. Removed from the wood mount, the edges of the mother-of-pearl pieces are filed smooth to fit, and pasted face-down into position onto the paper that carries the design.

A collection of mother-of-pearl bowls, stands and boxes from the rattanakosin era, in a display cabinet at Wang Suan palichat, Bangkok. the cone-shaped container is a tieb.

A mother-of-pearl door of phra Montien tham at Wat phra Kaeo, Bangkok, carrying the design of vishnu (narai) on garuda.

The embedding process then starts: several layers of lacquer are applied to the object to be decorated, as described on page 15. While the last layer is still sticky, the assembly of mother-of-pearl pieces on their paper backing is pressed down onto it, paper side out. Once the lacquer is completely dry, the paper and paste are washed off with water.

There still remains a difference in the level between the mother-of-pearl and the lacquer, so the intervening spaces must be filled in with repeated applications of a mixture of lacquer and pounded charcoal (from burnt banana leaves or grass) known as rak samuk. After each application, the surface is carefully polished with a whetstone and a little water, and allowed to dry; the process continues until the mother-of-pearl is finally covered. After thorough drying, the surface is polished with dry banana leaf and coconut oil until the mother-of-pearl appears perfectly and smoothly embedded.

Not surprisingly, such a laborious technique is rarely used nowadays. Modern designs are less complex, and the mother-of-pearl is glued directly to the usually wooden surface of the object. Black tempura and filler are then used for the embedding: lacquer is often not involved at all. The pieces here, including the tieb, a receptacle with a cone-shaped cover used for offering food to monks, are, however, from the old school—magnificent examples of the Rattanakosin period.

Sangkhalok Ware

khrueang sangkhalok

Some of the finest ceramics from Southeast Asia were produced in Thailand between the late 13th and 15th centuries, at the height of the Sukhothai period. The most famous site was an area of kilns a few miles north of Si Satchanalai, the twin city of Sukhothai. Excavation in the early 1980s revealed just how extensive the production was: this was virtually an industrial complex, with two centers close to each other, at Ban Pa Yang and at Ban Koh Noi. At the latter alone, there were over 150 kilns in a little over 0.39 square miles (1 square kilometer).

The ceramic production from here is now generally known as Sangkhalok ware. One explanation for the name is that ‘Sangkhalok’ is a corruption of ‘Sawankhalok’, which was another name for the area and is today the name of a small town between Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai (and which, incidentally, has a fine museum devoted to these wares). Another theory has it that the name derives from the Chinese Song Golok, meaning ceramic kilns of the Sung period. At the time, the Chinese ceramic export industry dominated Asia, and while the Sangkhalok production did not reach the same level of quality, its prices were lower. This stimulated healthy exports to other Asian countries, as far afield as Japan and Korea. Whatever the etymology, the name stuck, not only for ceramics from the complex near Si Satchanalai but also the kilns in and around the city of Sukhothai, including a group of 50 close to Wat Phra Pai Luang.

An ancient legend has it that one early Sukhothai ruler, possibly King Ramkamhaeng, visited Beijing to pay tribute to the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, and brought back some 500 potters. There is, however, no evidence of this, and stylistically if there is a suggestion of Chinese influence in the designs, it is much more likely to have come from Vietnam, which not only exported pottery to central Thailand in the 14th century, but also some craftsmen.

14th–15th century lidded pots and underglaze black painted vase from Si Satchanalai.

After 1371, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty placed restrictions on ceramic export and on private overseas trade, and this sudden unavailability provided the boost that the Thai industry needed. Si Satchanalai, and a little later Sukhothai, began exporting in earnest against competition from Vietnam. Recent diving discoveries of shipwrecks in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea show that this trade continued until the war with Burma in the middle of the 16th century. One route was south through Nakhon Si Thammarat, Songkhla and Malacca, another went east along the Cambodian and Vietnamese coasts.

The two kinds of kiln, cross-draft and updraft, were capable of producing a considerable range of ceramics, both earthenware and stoneware, but it is the clear glazed grey or white stoneware under-painted with designs in black that are the most closely associated with Sangkhalok. Of the two centers, the production of Si Satchanalai was superior, both in quality and quantity. The original reason for the siting of the Si Satchanalai kilns was the fineness of the local clay; Sukhothai’s, in contrast, was coarse and gritty, and its craftsmen were less skillful. On the best Si Satchanalai pieces, such as those shown above, the designs are dense and well-organized, while the export pieces from Sukhothai have a more limited repertoire, often with a chrysanthemum, a circular ‘chakra’ or fish in the center (see right). Tastes change, however, and the very simplicity and rapidly executed lines of the Sukhothai fish are now perceived to have considerable charm; it features prominently in modern production in this underglazed style.

painted stone plate with fish motif from Sukhothai; courtesy of the Sawanvaranayok Museum.

Celadon Ware

khrueang seladon

Celadon is named after a character in Honoré d’Urfé’s 1610 play, L’Astrée, a shepherd who wore a light green cloak with grey-green ribbons. Nowadays the name is used to describe a particular type of (mainly green) stoneware. The hue most popularly associated with the name is a pale willow green, but in fact it ranges from dark jade to white, with greys, yellows and greens in between. The precise color depends on the clay, the glaze, and the temperature and conditions in the kiln, which is high-fired to around 2282 degrees fahrenheit (1,250 degrees centigrade) in a reduction atmosphere. As one authority notes: “There has been a recent move to call celadons ‘greenwares’. This is to be deplored as many celadons are not green and many green wares are not celadons.” It is also worth noting that some modern chemical glazes that use copper or lead are not celadon.

In China, where it originated, it is still called green ware, and the subtly glazed classics of the technique are those produced during the Sung (Song) Dynasty (ad 930 to 1280). Some believe them to be the finest high-fired pottery ever made, on both technical and aesthetic grounds, and they have always been difficult to reproduce. Nevertheless, it was one speciality of the Sangkhalok kilns (see pages 18–19). Their best output is colored a beautiful sea-blue-green, and the glaze is usually rather shiny and glassy and much crazed. Since celadon glaze is difficult to control as it melts at a critical point, it was often not applied all the way down to the base, to avoid problems of it sticking to the support.

Contemporary celadon serving bowls with blue-green glazes. From the middle of the 20th century, thailand's celadon production has been revived and is now a major export.

A small ring-handled jar and a small urn for ashes, both Sukhothai-period celadon, at the Sawanvaranayok national Museum, Sawankhalok.

Jar with ring handles, Sangkhalok ware with cracked celadon glaze, also at the Sawanvaranayok national Museum, Sawankhalok.

Celadon was re-introduced into Thailand from Burma at the beginning of the 20th century, and has since then, in fits and starts, enjoyed considerable export success. The center of production is the northern city of Chiang Mai, to where Shans moved across the border on a number of occasions as part of re-settlement programmes. The Shan potters, who appear to have come from Mongkung in the Shan States, settled near the Chang Puak Gate in 1900, and began producing basic ceramic wares like pots and basins, with a rather dull grey-green celadon glaze.

Later, in 1940, when Chinese celadon became difficult to find, the Long-ngan Boonyoo Panit factory opened a little to the north of here, using the skills of the Shan potters to make household crockery. Although it lasted only a few years, it was followed by other operations, and eventually by the Thai Celadon Company. Since 1960 other factories have opened, producing varying qualities of output. It was common, even in Sung China, for there to be a slight crazing in the glaze, and even though an increase of just a few percent in the silica content would have avoided this, the network of widely spaced lines contribute aesthetically to the depth of the glaze. The jar with ring handles on right is a Sangkhalok ware with cracked celadon glaze. The range of wares that the several factories now offer has expanded to include blue-and-white, and also white, brown and bright blue monochromes, but the core of modern Chiang Mai production remains the traditional delicate green celadon.

A green Bencharong lidded bowl in the Jim thompson house museum.

Bencharong Ware

khrueang bencharong

The most exuberant of ceramics found in Thailand, highly valued among the nobility and wealthier commoners in the 19th and for some of the 20th century, was made in China. The motifs, for the most part, were distinctively Thai, with a cast of the religious and the mythological that included lions and divinities. The provenance, however, was not, and in these colorful, technically polished pieces we see nothing of the energetic and individualist ware from Sukhothai and Sangkhalok (see pages 18–21). There is as much reason for not considering them Thai artefacts, but in the end we do because they were chosen by the court and filled a decorative need.

Just as we see with the silk industry (see pages 114–115), overseas production—principally Chinese—was much more sophisticated than that produced locally, and it made more sense for royalty and nobility to import these pieces made to their specification than to build the necessary skills at home. The market was, after all, fairly limited. Bencharong was Chinese export ware aimed at the Thai market, beginning in the Tang and the Ming dynasties.

A collection of bowls, jars and dishes in a display cabinet in the house of former prime minister and literary figure Kukrit pramoj.

While the technique was Chinese, with its precise designs, rich colors and high quality over-glaze, the name is from Sanskrit (from which Thai script derives). It refers to the five colors commonly used: panch, meaning five, and rang meaning color, reworked in the Thai idiom. The five colors were usually red, yellow, green, blue and black, although today some designs use up to eight. Bencharong ware requires several firings, the colored enamels being added over the glaze each time. Set against backgrounds of vine and other vegetal patterns, the central motifs were mainly praying divinities (thep) and mythological beasts such as the fanciful lions (singh), the half human, half bird kinnorn and kinnaree (male and female), and the garuda (krut).

Antique Bencharong large covered jars (toh) and small covered jars (toh prik) may have been used for sauces and soups and cosmetics or medicines respectively. Courtesy of the Jim thompson house museum.

A variety of Bencharong, known as Lai Nam Thong, refers to the addition of gold, particularly to the rims of bowls. This addition developed to meet an increasing taste for sumptuous, unrestrained designs. Indeed, later Bencharong tended to feature Chinese designs as well as techniques.

Bencharong is interesting for what it shows of Thai taste and cultural leanings in the 19th century—the first half of the Rattanakosin period—when it flourished. As in so much else in Thai art, we can see an increasing love of decoration from Sukhothai to Ayutthaya to Rattanakosin. More than this, Bencharong reflected a royal fascination with China and things Chinese that blossomed with the reign of King Rama II (1809–1824). His son, HRH Prince Chesdabodin, directed trade between the two countries, and parts of the Grand Palace testify to the strong Chinese influence. King Rama III (1824–1851) continued the absorption of Chinese art and design, much of which can be seen today in Wat Phra Kaeo, but the decision by the Emperor to reduce foreign trade led to a decline in Bencharong imports.

This revived somewhat in the reign of King Rama V, who ordered Lai Nam Thong tableware for the palace. However, at the same time, Rama V was forging new links with the West. Ultimately, it was the collapse of the Chinese Empire, coupled with a transfer of Thai taste to things European, that sealed the fate of Bencharong.

Styles change, and change again. Today, Bencharong is deemed too ornate for most contemporary tastes, but even so the workmanship cannot be faulted. There is now some modern production in Thailand, but it falls squarely under the heading of airport art, made for tourists, and bears little comparison with the genuine old article. What the old and the new do have in common, though, is that they were and are both export ware. The difference is that the originals were made by some great kilns for discriminating clients.

Gold Jewelry

khrueang thong

In 1957, pillagers uncovered the country’s richest treasure trove: a hoard of gold objects interred in the crypt below the 15th-century tower of Wat Ratchaburana in Ayutthaya. Although much had been lost, archaeologists from the Fine Arts Department managed to secure some 2,000 pieces, including a spectacular collection of gold regalia, ornaments and jewelry. Now on display at the Chao Sam Phraya National Museum, the jewelry reveals the high level of gold workmanship, and the wealth associated with aristocratic life of the period. The gold button (opposite top), is one of these pieces.

The three necklaces shown here incorporate Ayutthayan gold work in modern assemblies, and all employ distinctively Thai design motifs. The leaf-shaped pendant, worked in a mixture of repoussée and chasing, (on left, above) is filled with wax to maintain its shape and detail, and is set with a single ruby. As remains customary, rubies (mined on the mainland principally in Burma, eastern Thailand and western Cambodia) were treated as cabochons, largely because of a regional preference for keeping as much of the weight of a gemstone as possible. The necklace on top right containing alternate gold and glass beads carries a solid engraved pendant representing a bai sema, the leaf-like standing boundary stone that is placed around the ordination hall in a monastery to mark the sacred space. The opaque blue-green beads are of Ban Chiang glass. The pendant on right, set with roughly faceted diamonds, is notable for its enameling: this technique normally using the three colors red, green and blue, as here, was developed in Ayutthaya.

Contemporary solid engraved pendant in the shape of a bai sema, the leaf-like standing boundary stone.

Modern necklace worked in a mixture of repoussée and chasing is leaf-shaped and set with a single ruby.

The manufacture of gold jewelry, however, did not begin in Ayutthaya. The Khmers, who controlled large parts of the country until the 13th century, certainly used gold, and pieces have been found at Sukhothai. The engraved slabs at Wat Si Chum in Sukhothai, illustrating the Jataka tales (which relate the previous lives of the historical Buddha), show figures wearing elaborate adornments, including necklaces and crowns. The 1292 inscription attributed to King Ramkamhaeng specifically allows free trade in silver and gold, although the wearing of gold was restricted by sumptuary laws to the nobility, and free use of gold ornamentation was allowed only from the mid-19th century, under King Rama V.

Antique gold button found in the crypt below the 15th-century tower of Wat ratchaburana in Ayutthaya, now on display at the Chao Sam phraya national Museum.

Modern pendant notable for its enameling.

Ayutthayan work was the high point in the history of gold jewelry. Nicholas Gervais, a French Jesuit missionary writing in the late 17th century was of the opinion that “Siamese goldsmiths are scarcely less skilled than ours. They make thousands of little gold and silver ornaments, which are the most elegant objects in the world. Nobody can damascene more delicately than they nor do filigree work better. They use very little solder, for they are so skilled at binding together and setting the pieces of metal that it is difficult to see the joints.”

Goldwork was revived under King Rama I in Bangkok after the defeat at Ayutthaya, and the enthusiasm of wealthy Thais for gold ornament was frequently noted by foreign visitors. Yet this very enthusiasm may ultimately have played a part in the decline of traditional Thai goldsmithing, for during the 19th century, when King Rama V became the first monarch to travel abroad, a number of foreign jewelers set up branches in Bangkok, including Fabergé. Clients with less refined tastes were catered to by Chinese immigrant goldsmiths. The Norwegian traveler Carl Bock wrote in 1888: “The manufacture of gold and silver jewelry, which is carried on to a large extent in Bangkok, is entirely in the hands of the Chinese.” Today, it is in the town of Petchburi, southwest of Bangkok, that the old tradition of goldwork is kept alive by descendants of early master goldsmiths.

Betel Sets

chian maak

Throughout South and Southeast Asia, the chewing of areca nut wrapped in betel leaf, for its intoxicating effect, was (and still is) a custom that transcended class, evolved rituals that helped govern social intercourse, and perplexed foreigners. Early Western travelers saw only effects that were, to them, fairly repulsive: blackened teeth, red-stained lips, and an abundance of spitting that left trails of red splotches on the ground. Yet, from India to the West Pacific, it has been a habit enjoyed by millions for at least 2,000 years (that is, from its first documented use in India). The offering of betel was a sign of goodwill to guests; affection in courtships; and honor at court. The preparation of the ‘quid’, or a packet of ingredients to be chewed, was considered an essential social skill. It was indeed the social significance of betel that not only surrounded it with paraphernalia, but also made the latter the focus of varied styles of craftsman-ship, some of it of a very high order.

19th-century mural from Wat phra Singh in Chiang Mai depicting betel being offered to a guest.

The betel set on opposite page, in gold repoussée, was from the court of Chiang Mai. The open cone-shaped receptacle contained the rolled-up leaves, which, in Thailand, were served folded in this shape rather than as an enclosed packet, as was usual in India and elsewhere. The other boxes housed the sliced nut, lime paste and optional ingredients such as tobacco, shredded bark, cloves and various flavorings. The ensemble was usually presented to guests on a pedestal tray, as depicted in the 19th-century mural at the monastery of Wat Phra Singh in Chiang Mai (above). The wooden betel tray (shown below), lightly lacquered with a decorative inlay of bone, is a more modest item.

There are three essential ingredients in a quid, which combine to create a euphoric effect and are as addictive, if not more so, than nicotine. The first is areca nut, called maak in Thai, a hard seed about the size and consistency of a nutmeg, which grows encased in a white husk and hangs in clumps from the tall, slender areca palm (Areca catechu). There is, incidentally, no such thing as a betel nut: that error crept into English around the 17th century through mis-observation. The betel is actually a green leaf—the second ingredient—from a creeper of the pepper family, Piper betle, or phlu in Thai. The third ingredient is lime paste, made from cockle shells that are baked to a high temperature to produce unslaked lime, to which water is added; it is then pounded into an edible paste. Cumin (Cuminum cyminum) is often added to the paste, giving it a red color.

Wooden betel tray, lightly lacquered with a decorative inlay of bone.

Betel set in gold repoussée from the court of Chiang Mai. it comprises an open cone-shaped receptacle for the rolled-up leaves, and boxes for the other ingredients.

The point of this unlikely-sounding combination is that arecoline in the nut is hydrolized by the lime into another alakaloid, arecaidine; the latter reacts with the oil of the fresh betel leaf to produce the euphoric properties. One side effect is that the saliva glands are strongly stimulated, which accounts for the large amount of spitting. The habit also resulted in the use of the flared, wide-mouthed spittoon, a common item in polite households. The characteristic red color of the spittle—and the issuing mouth—is due mainly to a phenol in the leaf.

Nowadays, it is more appropriate to use the past tense in describing the betel habit in Thailand, as modernization has largely overtaken the custom. You are much more likely as a visitor to a Thai house to be offered a soft drink than a quid of betel to pop into your cheek, and cigarettes are now generally a more preferred stimulant. In its day, however, betel certainly had its addicts. A German pharmacologist, Louis Lewin—as quoted by Henry Brownrigg in his book Betel Cutters (1991)—wrote in the 1920s: “The Siamese and Manilese would rather give up rice, the main support of their lives, than betel, which exercises a more imperative power on its habitués than does tobacco on smokers.”

As a footnote, it is interesting that while India is generally regarded as the home of betel chewing, the oldest archaeological evidence is actually from Thailand, where betel and areca seeds have been found in the Spirit Cave near Mae Hong Son, dating to between 5,500 and 7,000 BC.

Small silver box in the form of an aubergine. Fruit and vegetable silver containers have a long tradition in thai craft.

Small silver basket painstakingly constructed from plaited silver strips, and finished with coiled silver wire and beading.

Contemporary styled thai silverwork: a jewelry box with plaited exterior and an elephant lid, and hammered silver bracelets.

Silverware

khrueang ngoen

Silversmithing in Thailand follows an ancient tradition. Votive plaques from the 8th century have been found in Maha Sarakham Province in the north-east, and silver miniature stupas from southern Thailand date to the 11th century. The technical influences reached the country from all directions at different periods, and while techniques of working precious metals were probably first introduced by Indian traders, the strongest stylistic influences have been from Burma and China. The Burmese influence was felt most strongly in Chiang Mai, particularly at the end of the 18th century when the ruler, Chao Kawila, needed to re-settle the city after its long occupation by the Burmese: as he moved lacquer-working villages from the Shan States (see pages 13–15), he simultaneously brought in communities of Shan silversmiths. Since then, the Wua Lai Road area of the city, named after the original Shan villages from the Salween River, has maintained a silver-working tradition. This has been helped in recent years by the demands of the tourist industry, but has suffered a decline in quality for the same reasons.

In Bangkok, where the mainstream of precious-metal working took place, the formative influence was Chinese. It began at about the same time, in the Rattanakosin period. The whole issue of Chinese immigration into Thailand in the 19th century, almost all from Fukien and Kwangtung, is both fascinating and uncomfortable for many Thais, for while the Chinese quickly came to dominate trades such as silversmithing, they also eventually assimilated themselves into Thai society more thoroughly than in any other Southeast Asian nation. Both Carl Bock in 1884 and M. F. Laseur in 1885 noted that Chinese were dominant among gold- and silversmiths. In fact, silver was but one aspect of the situation; Friedrich Ratzel wrote in 1876, “while elsewhere they make their living mainly as merchants and only secondarily as miners and fishermen, in Siam they control the entire economic life.”

Ayutthaya-period repoussée silver box with the lid in the form of hanuman, the monkey deity from the ramayana epic.

While the Chinese brought new skills where silver was concerned, particularly in repoussée work, their tight guild organization excluded the Thais until the two groups began to intermarry. But over the years, their techniques spread outwards while they absorbed Thai stylistic influences. Sylvia Fraser-Lu, in her book Silverware of South-east Asia (1989), assesses it thus: “Their work has become virtually indistinguishable from that of indigenous Thai craftsmen. They are able to produce both Thai and Chinese-inspired objects with equal skill.”

In repoussée work, sheet metal is punched and hammered from the inside to produce a relief decoration. It is first coated in oil and then worked face down on a bed of resin. As constant hammering weakens the silver structurally, the piece being worked must periodically be annealed through reheating. This process forms a residue of black oxide, which must then be removed in a pickling solution of dilute acid. This procedure may have to be repeated several times, depending on the complexity and relief of the design. The background has been accentuated by punching down from the front, in a procedure known as chasing.

Traditional design of dressing table and mirror on a platform at Ban Mor, Bangkok. the height and the fixed angle of the mirror were designed for this to be used from a seated position on the platform.

Dressing Tables and Cabinets

khan chong lae tu

Traditional Thai household life was spent mostly on the floor. Kept spotlessly clean and sometimes covered with mats, the floor itself thus took the place of certain basic items of furniture, and obviated the need for others. In former times, such furniture as existed would have been restricted to storage units such as chests and small cabinets, mirrors, screens and couches, all made of wood. Very little furniture has survived from the Ayutthaya period, and none from the Sukhothai period; the oldest pieces one is likely to see are from the 19th century—the Rattanakosin period.

However, changes were taking place during the 19th century, particularly under the reign of King Rama V (1868–1910) who encouraged modernization and the influence of European styles and customs. Naturally, these changes at first affected only the wealthier Thais who had the closest contact with the court, but they then began to separate the basic customs of the upper classes from those of most of the population.

The furniture shown here illustrates this gradual change of lifestyle. The dressing table with mirror shown on top right, heavily decorated and on a low matching bench, is clearly designed to be used from floor level. Note the fixed angle, supported by the bodies of two naga serpents, to suit the position of a woman sitting on the floor. Nevertheless, while its decoration is fully Thai, this item of furniture is Chinese in origin. Indeed, almost all domestic furniture in what is now thought of as a traditional Thai style is influenced by Chinese models. This can be seen, for example, in the re-curved feet, in feet with a lion’s paw motif, and in corner decorations of beds and benches. During the Second Reign, from 1809 to 1824, the King was heavily influenced by Chinese design ideas (see the parts of the Grand Palace built during this period). This continued in the Third, and to a lesser extent in the Fourth, Reigns. Pure Thai style in furniture appears to have been restricted to ecclesiastical items such as the scripture chests and cabinets shown on pages 76–77.

The naga decorations running tail to head down either side are typical of this item. this piece is from the rattanakosin period.

Dresser and mirror in a room at the teak house, rama ii park, Samut Songkhram.

The changes ushered in by King Rama V brought a second layer of influence on furnishings and lifestyle, from Europe, and the cabinets pictured here show the hybrid combination of Western and Chinese motifs translated into a Thai idiom. The effect was ornate and fussy, but that was entirely in keeping with their purpose—new to the Thais—of displaying personal and treasured possessions. This itself was the chief European import, the idea of collecting objects to show off in the home to visitors, and it naturally demanded glass panels.

Glass-fronted and sided display cabinets in the Jim thompson house museum, used typically for showing ceramic collections.

A cabinet from the rattanakosin period that would have been used for storing household items.

Cabinets are known in Thai after the style of their legs, and there are four basic types. One is tu kha mu, or ‘pig’s trotter’ in which the legs are straight (and in actual fact not very much like a trotter); another has inward curving legs, known as tu kha khu; a third is tu kha singh (‘lion’s legs’), which have double-curved legs, the feet being realistically claw-like and often clutching a ball (as shown in photo on bottom far right); the fourth is tu than singh, also with lion’s feet but in addition a paneled base with concave grips for moving it.

Heavily decorated dressing table with mirror, also from the rattanakosin period. Chinese in origin, the mirror is kept at a fixed angle by two carved naga serpents.

A contemporary take on gilded-door cabinets, installed in the covered entrance to a house in central Bangkok.

A double-fronted display cabinet filled with mother-of-pearl ware. the rear panel of such cabinets were often painted color deemed appropriate to the collection and room.

Traditional living room with a thang used as a day bed, Ban Khun Chanchem Bunnag, Bangkok.

Table Beds

thang

This widely known piece of Thai furniture, exported frequently to the West, in fact has no generally agreed name in English. The Thais sometimes refer to it in English as a bench, which misses the mark, and while ‘Thai coffee table’ might well describe the use that it tends to be put to in a Western living room, this has nothing to do with its origins. That the thang has no simple, direct translation, despite its ubiquity, is evidence of the way in which the Thais adopted a Chinese item of furniture and made it more ambiguous. To say that it is a dual-use piece wrongly suggests that it was intentionally conceived to be put to one use (low table) or another (bed plinth). Instead, it drifted between uses.

The origin is the Chinese day-bed, which was never used with a mattress (that was reserved for the canopy bed), nor used exclusively as a table. This was the ta, and in its longer form the chuang, and was originally a simple platform and the earliest form of raised furniture in China. It took until the Ming dynasty for the early box-like form to develop into an open frame with four short corner legs, and it was this that reached Thailand. A Chinese writer, Wen Zheng-heng, proclaimed the virtues of the sitting platform, the ta, in the early 17th century: “There was no way in which they were not convenient, whether for sitting up, lying down or reclining. In moments of pleasant relaxation they would spread out classic or historical texts, examine works of calligraphy or painting, display ancient bronze vessels, arrange dishes of food and fruit, or set out a pillow and woven mat.”

A thang in the Jim thompson house museum, its resting, day-bed function stressed by the addition of a more modern mattress.