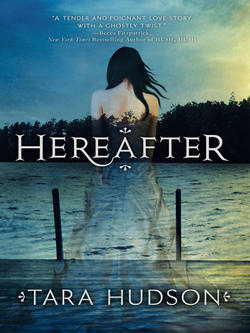

Читать книгу Hereafter - Tara Hudson, Tara Hudson - Страница 5

ОглавлениеChapter

ONE

It was the same as always, but different from the first time.

It felt as if my sternum was a door into which someone had roughly shoved a key and twisted. The door—my lungs—wanted to open, wanted to stop fighting against the twist of the key. That primitive part of my brain, the one designed for survival, wanted me to breathe. But a louder part of my brain was also fighting any urge that might let the water rush in.

The black water seized and scrambled and found purchase anywhere it could. I kept my lips pressed together and my eyes shut tight, though I desperately needed sight to escape this nightmare. Yet the water still entered my mouth and my nose in little seeps. Even my eyes and ears couldn’t hold it back. The water wrapped around my arms and legs like shifting fabric, tugging and pulling my body in all directions. I was buried under layers and layers of slippery, twisting fabric, and I wasn’t going to claw my way free.

I’d struggled too long, fought too hard, and now my body was weakening from the lack of oxygen. The flail of my arms toward what I assumed was the surface became less exaggerated, as if the invisible fabric around them had thickened. I literally shook my head against the urge to breathe. I shouted No! in my head. No!

But instinct is a slippery thing, too—ultimate and untrickable.

My mouth opened and I breathed.

And as I always did, except for the first time I’d experienced this nightmare, I woke up.

My eyes remained closed and I continued to gasp. This time my gasp brought hysterical gulps of air, but not the brackish water that had flooded my lungs and stopped my heart during that first nightmare.

Now the air was useless, purposeless in my dead lungs. I nonetheless felt a dull joy at its presence: although my heart no longer beat, the air meant I was no longer drowning.

Still, I felt a little silly for being afraid. After all, it’s not like you can die twice.

And I was already dead, that much was certain.

It had taken me awhile to accept the fact, perhaps years—time became a very uncertain thing in death. Years of wandering, confused and distracted by every sight and sound. Screaming at passersby, begging them to help me understand why I was so lost or even just to acknowledge my presence. I could see myself—bare feet, white dress, and dark brown hair that had dried into thick waves—but others couldn’t. And I never saw another person like myself, someone dead, so there was really no point of comparison.

The nightmares were what made me finally see, and accept, the truth.

At first nothing in my wandering existence brought back memories of my life, nothing but the elusive familiarity of the woods and roads I wandered.

But then the nightmares began.

I would suddenly and without warning fall into periods of unconsciousness. During them I would drown again. Only after the first few nightmares did I see them for what they were: memories of my violent death.

So the memories of my death had returned. Yet only a few memories of my life came with them: my first name—Amelia—but not my last; my age at death—eighteen—but not my date of birth; and, of course, the fact that I’d apparently thrown myself off a bridge into the storm-flooded river below. But not the reason why.

Though I couldn’t remember my life and what I’d learned in it, I still had some vague recollections of religious dogma. The few tenets I remembered, however, certainly hadn’t accounted for this particular kind of afterlife. The wooded, dusty hills of southeastern Oklahoma weren’t my idea of heaven; nor were the constant, narcoleptic revisits to the scene of my drowning.

The word “purgatory” would come to mind after I woke from each nightmare. I would play out my horrific little scene and then I would wake up, gulping and sobbing tearlessly, in the exact same place each time. It wouldn’t matter where I’d been wandering when I went unconscious—an abandoned railroad track, a thick grove of pines, a half-empty diner—my destination was always the same. And each time the nightmare ended, I would wake in a field. It was always daylight, and I was always surrounded by row upon row of headstones. A cemetery. Probably mine.

I never waited around to find out.

I could have searched for my headstone maybe. Could have learned more about myself—about my death. Instead, I’d pull myself up from the weeds and dash for the iron gate enclosing the field, running as fast as my nonexistent legs would carry me.

And so it was with my existence: a montage of aimless wanderings; an occasional word spoken to an unhearing stranger; and then the nightmares and subsequent hasty escapes from my waking place.

Until this nightmare.

This nightmare had started the same. And, just as it always did, it ended with a terrified awakening. But this time when I finally opened my eyes, I didn’t see the sunlight of a neglected cemetery. I saw only black.

The unexpected darkness brought back the terror, the frantic gasping. Especially since, after what would have been only one beat of my still heart, I recognized my location.

I was floating in the river again.

My renewed gulps, however, didn’t drag in muddy water that surrounded me. My body was still as insubstantial as it had been before this nightmare. It floated, unaffected by the drag and pull of the angry water. This time things were different, although the dark, twisting scene looked almost the same as it did in each of my horrible dreams.

Almost.

Because this time I wasn’t the one drowning.

He was.