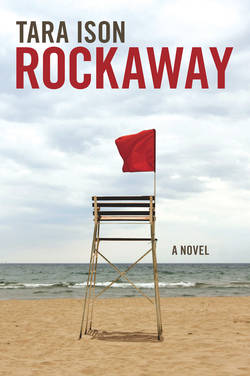

Читать книгу Rockaway - Tara Ison - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SHELLS

ОглавлениеTHIS IS WHAT I’ll paint, she decides: shells.

She is staying in a beach house at the last edge of asphalt before sand, a home that belongs to her best friend’s grandmother, who is away recovering from hip replacement surgery. She is here, emphatically, to paint. Back home in San Diego, a gallery owner, impressed by Sarah’s art store display canvases daubed with rich Old Holland oils, had proposed an exhibit. If there were some interesting, recent work, perhaps. Paintings that expressed and defined who Sarah is, now. This was an important opportunity, she realized, something worthy of focus. But can’t you paint here?, her parents had asked. There are too many distractions here, friends, work, family, she’d replied, hitting the fam hard, like in famine.

You’ll be fine without me, she told them. I need to do this. I need to get away.

She called her best friend in Connecticut, who’d married a millionaire and now had a country estate where they planted a garden for the pleasure of growing their own fennel and arugula. They raised sheep to knit their own lumpy, organic sweaters from. The cost of feeding and shearing the three sheep, and having their wool carded, came to over a thousand dollars a sweater. Sarah tried not to envy her friend these sweaters, but it was hard. Instead, she called the friend to request a haven.

Emily, about to have her third child by water birth, told her with kindness it wasn’t a good time right now, and then generously offered her Nana Pearl’s house in Rockaway, New York. Right on the beach, Emily said, it would feel like home. It would be empty for three or four months during the convalescence, except for Bernadette and Avery, the caretaker couple who lived in a studio guesthouse. She could stay there the entire summer. No one would bother her. The perfect retreat. And,

This’ll be really great for you, Sarah, Emily enthused into the phone. I’m so happy you’re doing this, finally.

Sarah quit her longtime default job managing the upscale art supply store in La Jolla, California, a blandly beautiful seaside town outside of San Diego where she had grown up. For years she’d shaved off ten percent of her paycheck and put it aside the way Mormons do to secure the earthly or heavenly future; she figured she’d saved just enough money to live, for a while. She gave notice on the beige, formica-and-asbestos, meant-to-be-temporary apartment she’d lived in since coming home from college, garage sale’d most of her kitchenware and furniture to San Diego State freshmen, and jammed the rest of her belongings, boxed-up and blanketed, into an 8’ by 7’ by 5’ storage vault she rented for thirty-five dollars a month. She broke up with her shrugging, default boyfriend, David. She packed up palettes and fresh brushes and fat, unpunctured tubes of paint, solvents, primers, and siccative oils, set her email to an emphatic auto-reply (I am currently offline and unreachable, away on a painting retreat!), and instructed her parents not to call.

Of course we understand, they said, of course we’ll be fine, don’t be silly, this will be so wonderful for you, go, go!

The Rockaway house—one of the oldest in the neighborhood, she remembers Emily telling her, 1902 or ’03—was surprisingly huge, dark gray stucco and fancy white trim, an awkward blend, she thought, of late-Victorian gothic and Cape Cod seashore glamour. The house, set off from the sea and sand by a low brick wall encircling the property, was at the dead end of a small flat street off Rockaway Beach Boulevard, at the western peninsula tip of Long Island, ten minutes of highway and one bridge across Jamaica Bay from Brooklyn. The house’s longest stretch on the second floor spanned seven bedrooms and three bathrooms linked without hallways, all with ceiling-high windows facing the gray-green Atlantic and full of wave crash and sea-tanged air. Her friend Emily’s mother Leah, plus Nana Pearl’s five other children, had grown up here; the house was peopled with photographs of these children, their children, and their children, including a recent shot of Emily with pregnant stomach and beatific smile, her husband and their two exquisite kids in their lumpy homeknit crewnecks. Dozens of eyes gazed on as Avery, the husband of the caretaker couple, guided Sarah upstairs, past walls collaged with grinny family photos.

“And this is Aaron, and Michael, Leah, and Rose,” he said, pointing. “And this is Rose’s daughter Susan, and this is Fran’s son and his girlfriend, and—”

“I know all these people,” Sarah said politely. She and Emily had been best friends since third grade.

“Ah, you are knowing Emily? This is Emily, with her husband and the children . . .”

They eventually arrived at the largest corner upstairs room, an oblong with huge picture windows on two sides framing the Atlantic Ocean like seascapes, gritty hardwood floors, threadbare rugs, and a queen-sized bed with a white iron headboard and flowered chenille spread. Waiting for Sarah was a large box shiny with packing tape, crammed full with the stretched and framed blank canvases she’d UPS’d ahead.

“This is a good room for you, yes?” Avery said in a booming, Sri Lankan lilt. He was a squat barrel-type man, ochre, tattooed, his bald head rooted solidly to his shoulders. “This is Pearl’s room. So much sunshine. You can be looking out. It is good for you and your painting.”

“It’s great. Really, thank you,” Sarah said. She swung open one of the picture windows, breathed in the turquoise light, the inviting sweep of beach, the steady seashell hum. She couldn’t remember when she last went swimming in the ocean, at home, but this ocean looked richer than the Pacific, more promising, as if undersea jewels and magical, tentacle’d creatures awaited. She graciously tried to tug her bags from him, which he had insisted on carrying for her.

“And here are many rags for you, for the painting. But I am thinking, you will not be lonely here?” He looked concerned.

“Oh, no. I’m here to work. I’m getting ready for an exhibition.” She smiled gaily at him, studied the room—the easel, that’ll go there, by that window, maybe clear off that nightstand, yes—and began to unpack her palette knives from the small wooden case she’d clutched to her side. I have an entire summer, she thought. Today is May 2nd. No, the 3rd. May 3rd, 2001. I have three months, maybe four. She envisioned filling her blank canvases with color, form, expression, and bringing them forth into the world, the rich smells of linseed oil and turpentine mingling with the ocean salt, infusing the house with her artistry, her presence. “I’m here for the working,” she said, in response to his skeptical face. “The being alone is good. It’s perfect. It’s what I’m wanting.” She hoped the gerunds would make it easier for him to understand.

IN HER FIRST moments on the empty beach—A walk first thing will clear your head, she tells herself, freshen and focus your vision, maybe you’ll even go for a swim in that promising sea—she spots a clamshell larger than she’s ever seen, sticking up from the sand like a highway-divider flap. She brushes it free of grit and plans to hold onto it as a keepsake of this time, until she realizes the entire beach is mosaicked with these huge clamshells, like expensive, themed floor tiling. She switches her allegiance to oyster shells, which, though plentiful, are smaller and harder to spot in the sand. Every day after her morning toast and coffee, then again in the late afternoon before tea and fruit, she makes a ritual of striding the sand to gather one or two oyster shells hued in grays, only the rare, perfect, unbroken ones. They look like little spoons, she thinks. If you were trapped on a desert island, you could collect oyster shells to make yourself spoons. She pictures herself shipwrecked, blissfully, eternally alone, living on seafood and shredded coconut, painting with fresh-squeezed squid ink and wild berry juices. She brings the shells up to her room—pausing to rinse them, and her bare feet, free of sand with the hose Avery leaves on the front porch—and lays them out carefully on the dresser top she’s cleared of Nana’s prolific family photos; as the days pass it looks like dinner service for four, then six, then eight, then twelve, awaiting a houseful of convivial guests and a course of soup. She shreds open her UPS box, carefully props her canvases against the walls of her room, arranged so their creamy faces can gaze expectantly upon her.

She remembers an old prison movie from TV, where the warden warns an incoming inmate in a voice lethal with courtesy: Your time here can be hard, or your time here can be soft. It’s all up to you.

Exactly, she thinks. She feels buoyant, untethered, full of faith.

“AH, YOU ARE finding a shell!” says Avery’s wife Bernadette. She has sooty hair in a thick spine of braid down her back, a wizened apple-doll face. Sarah has placed an albescent clamshell near the kitchen sink as a spongeholder, and Bernadette nods acceptingly at this new addition to the household. She and Avery comment on her every action when she’s in the kitchen—Ah, you are cooking now?—making her self-conscious. She had not realized they would all be sharing the kitchen, that she would feel so observed. They are intrigued by her way of roasting broccoli, how she disassembles an artichoke. So much work, grinding the coffee beans every morning! Do you not like spicy food? they query in thunderous voices, making her feel bland and defensive. They are the type of intrusive people she always winds up being unavoidably rude to, and then feeling guilty about. She begins taking her meals on plates up to her studio/bedroom, ostensibly to eat while she paints. When they cook, after she’s left the kitchen, their shouted, mingled lilts to each other and the smells of curry and cardamom waft.

During beach walks her head pulses with the (interesting, recent) art she will make. Images flash in bold, flat-bristled strokes; shapes and colors snap like flags. The new work will offer insight. Will communicate and express her vision. But when she returns to her easel overlooking the sea, the visions split off to pixels, scattered as broken bits of shell in the sand. Her blank canvases stare at her, wide-eyed and waiting. The pulses creep into faint throbs at the back of her head.

Relax, Sarah, she tells herself. You haven’t done this in a while, is all. You’re not used to having this kind of time and focus and space. You’re still acclimating. Don’t overworry it.

She starts carrying a sketchpad with her on beach walks, one of the many bought for this sojourn, all hard-backed like bestsellers. She dutifully strolls back and forth along the shoreline, admiring the expansive and eclectic beachfront houses—Cape Cod, Queen Anne, Art Moderne—sits on a baby dune of sand, cracks the pad open to thick, blanched pages. But then, sitting and clutching a stick of pricey high-grade charcoal, she sees nothing. Her hand wavers over the page as if palsied. The sunlight hurts her eyes, blanks out her brain. The breeze threatens her with grit. It is oddly chilly here, for summer. She retreats into the house with the sheet of paper ruined, crisped from sun and sticky with salt, all for nothing.

The tap water here runs out cloudy; when she fills a glass she must pause for the swirl of opaque minerals and molecules to settle. The glass clears from the bottom up, fizzing slightly, while she jiggles a foot, holding the slippery glass carefully, waiting.

You have to remember, she thinks: Rituals take time. They are invisible in the happening, we don’t see them until they have become.

She decides not to shower or wash her hair until she has completed one perfect painting.

BERNADETTE AND AVERY recycle; there is a box for used cardboard and paper, one for glass, one for plastics, one for metals. One bag holds flattened aluminum foil, veined from use. They pillage the kitchen trashcan, looking for anything that has slipped through the system. Sarah is annoyed at their quizzical examination and redistribution of her wrappings and peelings. She takes to packing up her garbage in her backpack—the empty bottles, the hair combings, the used dental floss and tampons, the ruined sketch pages—to drop privately in a public Dumpster when she goes into town, and listens to the explosive, packaged clink of breaking glass with satisfaction. She has walked to and from the nearby specialty deli shop twice, carrying her milk and produce, overpriced German beer and French pinot noir, an expensive bag of coffee beans, the splurge on ultra-dark European chocolate, but eventually Avery insists on the need for a bicycle—the nearest grocery store is thirty blocks away, down the long strip of Rockaway Beach Boulevard that spines the length of the peninsula. He pulls from the shadowy garage a girl’s rusting bike, left by one of Nana’s children or grandchildren, wheels it down the driveway. He affixes a pink wicker basket, fusses happily with bolts and air pressure and alignment. She watches, nervous, eyeing the back-and-forth traffic down on the boulevard, tucking the hems of her long cotton pants into her socks; she has not ridden a bicycle in years, is embarrassed at her awkwardness in mounting and her little yelps of fear as she test-pedals around their quiet dead-end street. A subtle memory teases: her father teaching her to ride a bike, she remembers, sees him running alongside, patient and panting in warm summer sun, holding the high looped sissy bar steady so she won’t fall, then letting go, watching and cheering her on. She remembers breeze, the sense of freedom and flight, then relives the sudden wobble, the panic, the skid, an abrupt falling, the hot pain of skinned knees leaking small grids of blood. She remembers his feet, adult rubber soles running to her, his strong adult hands and comfort murmurs, the soothing sting of antiseptic. The reassuring plasticky smell of a Band-Aid. Okay, so you’ll be okay, Sarah? Then let’s get you back on that bike! Climbing back on that bicycle, yes, steadied for her by his hand and encouraging smile. She remembers her newly emboldened pedaling. She smiles at the memory. Faint as ghosts now, all those babyhood scars.

She shakes her head, and clutches harder at the handlebars. Avery, clasping a wrench, nods approvingly and points her toward civilization. She turns onto Rockaway Beach Boulevard, gasping a little at every jolting chink in the road, accompanied by the tinny and self-generated pling pling of the bicycle’s bell. Cars pass her by like benevolent sharks, and ten or twelve blocks along finally she relaxes enough to unhunch her shoulders and look around.

It’s a time-warped, patchwork little neighborhood, a jumbled mix of blue-collar row houses with tiny, well-tended front-lawn patches of grass, larger Arts and Crafts bungalows with encircling porches and wicker furniture, modest mid-century ranch-style homes, and the odd glass brick-and-concrete Postmodern effort, all of it entirely unlike the faux-Mediterranean, gated-community sprawl of La Jolla. She remembers Emily’s history of Rockaway, the once-upon-a-time playground of elite New Yorkers looking to escape the city heat and summer at the beach; now there are large, shabby-looking buildings in the distance—housing developments? she wonders, warehouses, abandoned factories?—bruising Brooklyn accents—although yes, she remembers, Rockaway is technically part of Queens—kids yelling in Spanish and the constant thwunk of basketballs somewhere on cracked schoolyard macadam. She passes so many synagogues, yeshivas, and Catholic churches she begins to wonder if she is pedaling in circles, until she spots the commercial district up ahead, at the intersection of the boulevard and Beach 116th Street. There is a liquor store, a Baskin-Robbins, and a lingering Blockbuster, a chain grocery store she has never heard of, two hardware stores, a Chinese restaurant, a CPA, the dime store where Avery works part-time, a Buy the Beach Realty, and a Pickles and Pies Delicatessen—Egg & Roll, $2.39. There is the subway station for the A train that sweeps down through Manhattan for its long stretch across Brooklyn and Queens, tunnels beneath Jamaica Bay, and emerges onto the Rockaway peninsula to spit out weary passengers. There is also a ladies’ apparel place, which Sarah at first mistakes for a vintage clothing shop, offering the print dresses and quilted housecoats her grandmother used to wear, the window mannequin wearing a sagging nylon brassiere and cut off at the waist. She buys turpentine at one of the hardware stores. She buys a knish.

In a junk shop she finds a thick book: A Collector’s Guide to Seashells of the World, which she buys with the notion of identifying some of those scattered shells she’s seen; her walks on the beach, now, will be purposeful, will be research. She pedals home on the rickety plinging bicycle, her thighs burning. The pretty cover photo of a mollusk trembles in the wicker basket—This is what I’ll paint, she thinks, pleased: shells—and she rides over the road cracks carefully; there is a new half-gallon of merlot in her backpack, and she worries that if she falls the bottle will shatter and a shard will puncture her, nick her spine or pierce a lung.

When she gets the book home, however, she finds the written part of A Collector’s Guide to Seashells of the World laborious, obsessed with classification and boggy Latin words; Mollusca-Gastropodae-Mesogastopoda-Cypraeidae-Cyprae-Tigris bears no relation at all to the glistening tiger stripes, the whorls, the fierce horny spines, the sinuous geometries, the corallines and saffrons and ceruleans of the shells in the book’s generous color plates. She normally doesn’t like photographs, hears the impassioned rant of an old art professor: A photograph is a dead image of a dead thing! It’s painting, a painting, that creates and gives life! But she has to admit the color photos outshine the prosaic, monochromatic shells she’s actually found on the beach. Perhaps the photos will serve as a prompt, she theorizes. The juxtaposition of glossy dead thing with imperfect real specimen. And so she spends an hour or so each morning leafing through the book over her fresh-ground, cooling coffee, idly admiring the rainbow color rays of gaudy asaphis clams and the fluted projecting scales of giant clams, also known as crypt-dwellers.

THERE ARE THREE different kinds of sand to walk on, she discovers. On the other side of the low brick wall that marks Nana’s property, farthest from the water, the sand is dry and siftable and pale as snow, the warmest to bare feet but the most dangerous with its buried broken things, sharp fragments of plastic and glass, bits of abandoned toys.

The next section is slightly damp, toughened and stiff from the last lunar swell of surf, and the most obstacled with shells, seaweed, ragged seagull feathers, twisted limbs of wood. This sand almost carries her weight without breaking the surface.

Then the wet, darkest sand, briefly and constantly re-soaked with each slow roll and break of a wave. When she steps here she craters the sand for a mere second before her foot trace is swirled away. She lingers, slushing her feet back and forth in a few inches of cold briny water, liking how she seems to disappear with each step.

When she heads back to the warm sand up by Nana’s, she notices a man in shorts studying the house, thick-torsoed but with long and shapely legs like a cocktail waitress; he exits the beach onto the small street and disappears from view. Another man, she notices, is sitting placidly on Nana’s wall, wearing sunglasses, a dark sweatsuit, and black knit cap, curly hair fringe flapping in the breeze. He is unshaven, bum-like. She is annoyed at their presence; it is disruptive.

The early-May beach has been blessedly empty, the ocean and bright air still too chilly for bathers, not even a lifeguard on duty yet atop the high rickety chair facing the sea, and she’s used to having the span of shore all to herself. She is looking forward to swimming, soon; maybe she’ll begin each day with a brisk, invigorating ocean swim. She sits several yards away from the bum-like man and leans her back against the wall proprietarily, prepared to sketch. After a moment she pulls aside her long cotton skirt and exposes her legs, hoping to maybe get some color in the weak sun. She inspects her pale and stubbled calves and thighs, so dry these days, her skin, something she should take better care of. Maybe get some Vitamin E oil, they say that works well, diminishes the marks of time, of old scars. She rubs at her thigh, remembers glowing a perfect unblemished peach, her apricot child skin, her tender, once-upon-a-time skin. She drifts her fingers through the sand, sifts free a shard of glass, bottle-green, like old ginger ale bottles, she thinks, apricot and green, the vibrant colors of those little-girl summer beach days. The ritual stop at 7-11 to buy Coppertone and bruised blushing apricots and those emerald bottles of ginger ale to pack with crushed ice in the cooler. At the La Jolla Shores they’d choose the most isolated spot, stab an umbrella deep, spread beach towels extravagantly.

She always swam off by herself, she remembers, leaving her parents and baby brother with their radio and magazines and baby-boy toys. She remembers the happy stumbling sandy run, the blithe, flapping free dive into the sea, the euphoria of swimming deep. The brief fear as the solid world dropped away beneath her, then surfacing, feeling and realizing the effortless float, the joy of floating free, arms outstretched to greet the next wave. And after each wave came, flipped and roiled her underwater like a scrap of paper and dragged her back to where the ocean broke down and thinned, she’d scramble up from the seaweed and sand crabs, cough, and look for them, her parents, eyes burning and searching and the start of another fear, of panic, but there, always, every single time, there they are. Her parents, watching for her.

Her father waves, proud and affirming, her mother applauds overhead, making it okay to swim back out all over again alone to meet and conquer the next swelling, frothing wave. When she has enough brine in her throat she staggers back, to her mother’s fresh palmful of coconutty Coppertone, a popped-open bottle of that cold ginger ale, a piece of bruised fruit sweating ice, sweet things to cancel the salt and soothe. A brisk rub with a sun-hot towel, their admiration and cheers for a discovered shell, a perfect seaweed fan, the tiny sand crab she’s carried home in her cupped palms, the painstaking drawing she’s made—Mommy, Daddy, come see, come look!—of a perfect seahorse or mermaid or happy family of fish in the damp sand.

You should give them a call, she thinks, blinking. Really, you should call, see how they’re doing, if they need anything. You should check in with them, they’ve been so understanding and supportive and not bothering you. She studies the piece of glass, so careless of people, really, to bring glass things to the beach, just breakage waiting to happen and then all those glinty bits hidden in sand, lying in wait for soft feet and fingers and toes . . .

“Hey!”

She is startled, looks up. She spots the man in shorts exiting the front gate of Nana’s house, approaching. She flips her skirt back down again.

“Hello?” she inquires.

“You Sarah?” he asks loudly.

“Who are you?”

“You know Susan?” Susan is her friend Emily’s first cousin.

“Uh, yeah.”

“I’m her dad’s brother. You know Rose, right?”

Rose, Sarah knows, is Susan’s mother, her friend Emily’s aunt. One of Nana Pearl’s four daughters. Rose was divorced from Susan’s father Bruce when Susan was seven. Sarah knows the twining course of Emily’s complicated family history as well as she knows her uncomplicated own, all those Emily-family gatherings she’s attended, the holidays, weddings, Bar Mitzvahs, graduation parties, the being invited along to birthday celebrations in Catalina, their clannish ski trips to Vail.

“Uh huh,” she says.

“Yeah, I still talk to her a lot, you know, she and Bruce’re still pretty good friends. Heard you were here. Thought we’d come by, say hello.” He gestures behind her, to include in his we the man still sitting on the wall, who is ignoring them, studying the sea.

“Oh. Hello.”

“So, you’re what, on vacation?”

“No, I’m here to paint.” She closes her sketchbook, picks up her sandals, rises; she will have to pass right by him to get to the house. She puts the piece of glass in her pocket, to dispose of properly in Bernadette’s kitchen recycling.

“Oh, hey, you’re an artist?”

“Well,” she says.

“Great. Hey, Marty,” he yells, “we got an artist here!” The man on the wall finally looks over at them, and nods. He swings his sweatsuited legs over to their side, like a concession.

“So, what, you want to go for a walk with us?”

“I was just about to get back to work,” she says, approaching them. “I’m here for painting. I’m getting ready for an exhibition.” Mommy, Daddy, come see, come look! she remembers.

“Oh, come on, take a break. Come for a walk with us. Marty,” the man yells, “come get her to go for a walk with us.”

“What’s your name?” she asks.

“I’m Julius. Bruce’s brother Julius. This is my friend, Marty. We grew up together. Marty still lives here, just a few blocks over. Tell her, Marty.”

Marty points in the direction of a few blocks over.

“Yeah, Marty’s an artist, too. Musician.” Julius tells her the name of a band that sounds slightly familiar, like a group mentioned in a Sounds of the Sixties album commercial. “Big glory days. Ever hear of them?”

“Maybe.”

“So, there, see? Come on, come for a walk with us.” He reaches, puts his hand on her arm, and she is glad to be wearing a long-sleeved blouse. He has skin either an enhanced or natural nut brown, and a ruby red, pouty lower lip.

“I don’t know . . .”

Marty strolls over. He takes off his sunglasses, looks at her inscrutably, and nods. Closer up he looks like a pleasant-faced but aging actor in a going-psychotic role.

This is how women’s cut-up bodies wind up washing ashore, she thinks. This is how it starts.

AS THEY WALK along the shoreline, on the damp, toughened strip of sand, Julius tells of his youthful escapades. A buddy once invited him to a concert in New York and he found himself on a helicopter to Woodstock, where, Jimi Hendrix’s manager having not shown up, Julius walked around for the weekend wearing Jimi Hendrix’s manager’s security badge and doing drugs with John Sebastian. Another time he wound up schlepping a suitcase of opium across Europe, and getting busted in Israel. They kept him in jail for six months, finally letting him go the first night of Hanukkah, he thinks, because he’s a Jew. Not much of a Jew, hafta say, Julius says with a laugh. Now, Marty, that’s a Jew, a real Jew. He’s started keeping kosher, the whole bit. Getting conservative on me these days.

Marty bobs his head in good-humored acknowledgment.

“You Jewish?” Julius asks her.

“Yes. But not much of one, either,” she says.

Now Julius is a stockbroker in Manhattan. He still keeps in touch, though; he manages a Cuban musician and twice a month flies to Havana for club dates and banana daiquiris at one of Hemingway’s favorite bars.

“Seventeen dollars for a daiquiri!” he says. “You gotta come sometime.”

“Are you still in music?” she asks Marty.

“I play around a little,” he tells her.

“He still tours,” Julius says. “He’s got a doo-wop group, they do revival, you gotta hear ’em sometime. And he scores movies. They’re filming a big movie over in Brooklyn,” Julius says. “Marty’s on the set every day.”

“That sounds interesting.”

Marty shrugs. “I mostly produce for friends, do some mixing.” He glances at, then away from her. “Whatever.”

They pass one of the decaying old buildings she has wondered about, three stories of smashed windows and graffiti’d brick, a chain-link fence. “What is that, do you know?” she asks. “It’s horrible-looking.”

“Old age home,” says Julius. “Been here forever. They got it shut down, now.”

“It’s like some Dickensian orphanage.”

“Marty, you had someone in there, right? Your uncle?”

“Yeah.” He nods. “Old guy. Died in there when I was a kid.”

“I’m sorry,” Sarah says. “That’s so sad.” She smiles in sympathy, envisions a lonely old man, abandoned by family and friends, lying on a cot, withering away to the unrelenting sound of seagulls and crashing waves, the smell of aging bodies and industrial disinfectant. Marty doesn’t look especially sad, however, or say anything more, and her words sound insipid, hanging there. “So . . . are they going to tear it down?”

“No, they’re re-doing it,” he says. “It’ll be a community center or something. Maybe a new school. There’s good stuff coming, here.”

“Yeah, he keeps saying.” Julius nudges her. “This whole place went to hell a while back. Great when we were kids, but the late sixties, the seventies, you know, economy tanked and people got the hell outta here. I been trying for years to get this guy to move to the city. You gotta move to the city, I keep telling him.”

Marty nods good-naturedly.

“He won’t budge. Says it’s all coming back these days. It’s your life, I tell him.”

After another hour of walking, Julius says he’s hungry. It is now late in the afternoon, the sun has sloped, and it’s too late, she thinks regretfully, to paint.

“What’s that place you were talking about around here, Marty? The seafood place?” Julius asks.

“Lundy’s. But that’s in Sheepshead Bay. We go after shooting, sometimes.”

“Let’s go. You like seafood? I’m starving.”

“You know, I’ve never been to Brooklyn,” she says. “I picture it like in movies. Moonstruck. Goodfellas. Woody Allen stuff.” She glances at Marty, to include him.

“I don’t want to eat yet,” says Marty.

“You want to come for dinner?” Julius asks her; she hesitates, unsure whether Marty has merely postponed the dinner, or declined his inclusion entirely.

“I don’t know . . . I should still get a few hours’ work done.” There’s spinach left, she thinks, and pasta waiting for her. I might open a can of tuna.

“Tell you what, gimme your number, I’ll call you in an hour.”

“Okay . . .” She scribbles on a page of her sketchpad, rips it off, hands it to him. She wonders if Marty will be hungry in an hour.

“What’s this?” Julius asks.

“The phone number.”

“This’s the house number. My brother, he’s married to Rose eighteen years, you think I don’t know Pearl’s telephone number?” Julius takes the scrap from her and passes it to Marty. “Here. You keep that.” Marty shrugs, and puts it in the pocket of his sweatsuit. He nods at her, turns, and strolls away, heading back along the shoreline toward the Rockaway homes. Julius takes out his phone. “Gimme your cell. I’ll program it in mine. See? We can do this now. Look how good this works.”

Julius doesn’t call until seven-thirty, at which point Bernadette and Avery have already taken over the kitchen with some kind of stew, are banging pots, bellowing at and around each other. Julius’s first-person pronouns indicate he’s coming to pick her up alone. She’s hungry, and the yelling in the kitchen is giving her a headache. She decides to go to dinner, but also decides, at least, that she will partly stick to her resolution and not wash her hair. An assertion of indifference.

“Do you know Julius?” she inquires of Avery as he pours out basmati rice from a massive burlap sack he and Bernadette keep in the storeroom off the kitchen.

“Ah, Julius. Yes, he is uncle to Susan, I think. You are going out?” He seems very pleased, relieved almost, that she will not be having her dinner alone.

I have been eating my dinner alone by choice, she wants to tell him, but says nothing. She just smiles, nods, and exits by the kitchen door to wait outside the house.

“We will be keeping the light on for you, yes?” he booms after her.

WHEN SHE GETS into Julius’s car, a metallic gold Jaguar, she breathes in air freshly sweetened with men’s cologne; it troubles her for being as unperfumed as she is, and also for its scent of expectation.

They leave Rockaway, and, as they drive across the Marine Parkway Bridge, he asks her if she’s ever been married. She says no, and then decides it’s blatantly rude not to return the question.

“Nope. Lived with a lady for twelve years, though. Moira. Irish Catholic girl, there you go. Should find me a nice Jewish girl. Have kids. Not too late for me, huh?”

She smiles, nods, peers out the window. “Hey, Flatbush Avenue,” she says. “I guess I am officially in Brooklyn. Looks like a big field.”

“Yeah,” he says. “We’re going through Marine Park now. That’s Bennett Field, over there. Lots of famous places around here. I’ll drive you by Coney Island, later. Brighton Beach. Better in the day, though.”

At Lundy’s he propels her to the oyster bar and announces his plan to just begin the evening here, for cocktails and appetizers. A chalkboard listing freshly caught options hangs on fishnet over their heads. Julius orders from the bartender—a guy dressed as a pirate, briskly quartering lemons—vodka martinis and a half dozen each of littleneck and topneck clams, and Wellfleet oysters. She has never heard of Wellfleet and decides to look up their classification in her book when she gets home. Julius cocks back his head and lets an oyster slide from shell to throat; she instead uses her tiny fork to rip free the oyster’s last clinging shred and transfer it primly to her mouth.

“They’d make good spoons, wouldn’t they?” she says, replacing the empty oyster shell in its berth of crushed ice. “I’ve been collecting them on the beach. I feel like I’m choosing flatware for my bridal registration.”

“What, honey?”

“Oh, nothing.” She touches her lips to her martini, and reaches for a littleneck. The oyster pirate brings her another martini at Julius’s crooked finger, then, smiling, shucks oyster after oyster. She wonders if he ever cuts himself by accident. She wonders if the lemon juice from all those wedges burns.

He asks if she has any kids, and she tells him No, but she is very close to her parents. They’re a very close family. Her parents are just wonderful. They’re getting older, though. She tells him her mother is in poor health now, liver problems and maybe a transplant down the road, that her father has just been diagnosed with prostate cancer. But early stage. They are treating it with hormone therapy, she adds, sipping her martini, and are all very hopeful.

“Yeah,” he says, nodding enthusiastically. “Hormone therapy. They say that works great, can sometimes do the whole job. Or maybe with the radiation they do. The younger you are, that’s when it’s bad. But you get hit at sixty-five, seventy, you’re okay, you know? Something else’s gonna kill you first.” He seems contemplative and informed on this subject, and she realizes, after all, that he probably isn’t that much younger than her father. “It’s nice they got you to depend on now,” he adds.

“Yes,” she says. “I live, well I lived, just down the street. I do their shopping, take them to their appointments, stuff like that. They’re fun to cook for. I like to make them special meals, healthy things, you know. Nonfat sour cream. Hide the vegetables.”

“See, that’s really something, a daughter like you. Really something.” He nods approvingly at her, and she smiles, basks a little, then waves away the compliment.

“Oh, they’re wonderful. They’re doing great. Really strong. They’ll both probably live a long, long time, yet.” She takes a healthy swallow of martini. “Thank God.”

The shrimp cocktail arrives; a rhomboid dish of thick crimson sauce, the shrimps clinging to its glass rim like drowning people clutching at a lifeboat.

When the check comes she pokes her hand at it, but Julius bemusedly slaps a credit card on top, away from her. The oyster pirate smiles knowingly at her and she understands, with Julius paying for the evening, that she now has a duty to be a charming, attentive companion. She needs to stop discussing stupid and unkind things like prostate cancer and oyster shell bridal spoons. The thought of the rest of the evening still to go like this exhausts her.

“You look a little like Anthony Quinn,” she tells him.

“Yeah?” he says, pleased. “Hey, see, then I got time yet. He was still having kids up till the end, right?”

“Right,” she assures him. “Never too late for a fresh start.”

Before they leave he loudly asks the manager where to go for real Italian food around here; she thinks this is meant to underscore for her that while he once was from here, he is now from Manhattan. The manager snaps up a card from a large clamshell on the counter, scribbles, and hands it to him. “Marino’s,” he says. “Eighteenth and a hunnert sixty-seven. Ask for Dean. Tell him Larry from Lundy’s sent yover.”

Julius gets lost. They drive through brightly lit Little Odessa, on a tunnel-like street beneath an elevated train, where they pass pierogi stands selling homemade borscht and Russian nightclubs advertising acts in neon Cyrillic letters. That was a great trip, she says, when I was in Russia, and launches into the story of traveling Europe the summer after college, before she was supposed to move to Chicago for grad school, the tour meant to study Balthus’s naked little girls at the Pompidou, Goya’s witchy women, gouaches in the Prado—she remembers roaming careless and carefree, lightweight everything tossed in a nylon backpack, the gossamer-float sense of skimming trains—and tells him how, the funny thing of the story is, really, that her most vivid memory is standing in line for hours outside the Hermitage to get real Russian vodka, how there turned out to be a glass bottle shortage and so vodka was doled out in condoms, seriously, men rushing home with their drooping latex phalluses of booze, but Julius interrupts to point out Coney Island in an open-ended way, as if expecting her to want to ride the rollercoaster. She then tries asking questions about his work in Manhattan, his upcoming trip to Cuba, but finally realizes his constant What, honey?s and What, sweetheart?s in response means he’s rather deaf. But he doesn’t seem particularly ill at ease with silence, so she stops talking at all.

Marino’s is on the other side of Brooklyn, and in the end it takes them fifty silent and cologne’d minutes driving through revolving strips of Ethiopian, Russian, Italian, Hassidic, and Puerto Rican neighborhoods to get there. To her dismay, they are told there will be a forty-five minute wait, but Julius hands Larry-from-Lundy’s card to the maître d’ to give to Dean, and they are immediately seated in the prime booth of a black and pink Art Deco room with vertical strips of mirror on the walls. Julius pre-orders the chocolate soufflé, requests another round of martinis, which, when they arrive, he announces inferior to martinis in the city. It’s the vodka, he tells her, they try to pass off the cheap stuff. He lists better restaurants in Manhattan he will take her to. Over the penne arrabiata he inquires with circuitous and excessive delicacy how old she is and then seems both surprised and disappointed at almost-thirty-five; she feels briefly guilty, as though she’d deliberately sought to tantalize with the false impression of fertility and youth. She reassures him of her ability to impersonate twenty-something with the story of how she still gets carded in supermarkets when she buys wine. He seems cheered and charmed, too, by the fact that she purchases her wine in supermarkets, and promptly orders three glasses of the restaurant’s finest cabernets, in order to cultivate her palate. She pretends to be able to discern a difference and insists on drinking down the three glasses by herself, to avoid his getting drunk and aggressive or getting them killed on the drive home. When she asks how old he is, he coyly tells her the year of his birth and makes her do the math.

Fifty-seven, she figures. No, fifty-eight.

“Most shells have a life span of about two to fifteen years,” she says. “The larger ones live longer, they can make it up to seventy-five.” My father is only sixty-six, she thinks.

“What, sweetheart?”

“Thank you very much for dinner,” she says loudly.

“Yeah, pretty lucky I found you out there today, on the beach,” he says, looking happy. “Thought that was probably you, sitting there. I knocked at the door, but no one was home. Pretty lucky.” She doesn’t point out the lack of luck involved—that if she hadn’t been sitting on the beach, she likely would’ve been in the house. She decides to let him think he has found something.

When he offers her a sip of his after-dinner Frangelico she gulps three times.

Her seatbelt is unbuckled five houses down from Nana’s, and when he slows then stops the car she leans in quickly to peck him on the cheek; he clasps the back of her head with his abalone-thick hand, holding her face against his for an extra moment.

“You want to maybe have dinner Friday? I’ll know tomorrow if Cuba’s happening this week or not, I’ll call you.”

She hurries into bed without toothbrushing or face-washing; his cologne, cloying and stale, she finds when she awakens in the morning, has transferred from his face to her cheek, to her pillow, to her sweater, and drifts through the rest of the house, mingling with the curry for days.

SHE LOOKS FOR mussel shells. Most are broken; all have been snapped into halves. After two hours’ search she comes upon a perfect, intact bivalve; its sides are still held together by a fragile, drying ligament, but strained apart, gapped like castanets or a Munchean scream. She peers inside, but any trace of meat is long gone. There is something mythological here, something insightful and interesting; she remembers what she thinks is a Greek philosopher’s theory of male and female halves, once joined together in human form, now split apart in two drifting, searching sexes. She examines the empty and strained shell, noting its creamy nacre is worn from exposure, its hard beryline surface starting to fade, its chipped edges, its halves shaped like swollen, elongated tears. She hurries the mussel home. By the time she’s rinsing sand from her feet on the front porch she can’t conjure up what beauty or resonance she saw in the shell, only that it’s lusterless, and tacky with dry salt, and so decides instead to first make herself some scrambled eggs for lunch. Also, her head is pounding, from sparing Julius all that alcohol the night before, and so she opens a bottle of beer.

She passes through the cool dark hallways of the house, climbs the creaking stairs—Why does Nana need all these family photos everywhere? she thinks—to her corner bedroom, winces at the sudden glare of sun through all those windows. She has already made the bed, as she has conscientiously done every morning, stretching the chenille coverlet smooth. She has already put yesterday’s clothes in the hamper, already tidied the bathroom and aligned her toiletries and hung her towels, and neatly laid out her brushes on the nightstand. She has already swept up the traces of sand that always seem to creep into her room, despite the careful rinsing of her feet when she enters the house from the beach.

All right, she thinks. You’re all ready to begin. She selects a canvas, positions it perfectly on her easel. Mytilus edulis, she thinks, looking at her gaping shell. The common blue mussel. She seizes a tube of pthalo blue, punctures it open.

There. You have begun.

Then dioxazine purple. Aureolin yellow, viridian, ivory, iron oxide black. She studies the moist little squeezings of color on her palette. Even with the employee discount she’d spent a fortune on these studio-sized tubes in her wooden case: Old Holland, the best. Excellent strength of color and lightfastness, no cheap fillers, their pigments still fine-ground by old-fashioned stone rollers and mixed with cold-pressed, sun-bleached virgin linseed oil, each tube packed by hand. She has recited that to customers for over ten years, using her old college canvases as example and display, and, before quitting, purchased herself this grand spectrum. She must be careful not to waste them, all these rich colors.

The sun through a picture window reflects off the virgin canvas in a harsh, hurtful way. A blank canvas is awful, an insult, she thinks. A sin. You must overcome the sin of the blank canvas.

She seizes a brush. It is a ragged, windy day; sand flecks the window glass and the wooden frames are rattling in their sockets. She sets the brush down, contemplates the mussel, its faint pearlescence, then, determined, punctures one more tube and squeezes out a healthy dollop of rose dore madder. She picks up a palette knife, dips its edge, taps, makes pretty red dots on the palette. Like smallpox, she thinks. Measles. A coughed spray of consumptive blood. Focus, Sarah, she tells herself. Stop playing around. Carpe diem yourself. Seize this opportunity to express and define who you are, now. Fresh start.

She puts the palette knife down, swigs beer, and looks out toward the ocean. A seagull hangs, floats in reverse for a moment, fighting the wind, then flies away beyond her view. At the seam of horizon and sea is a large ship, a tanker, she decides, or some kind of freighter. A liner, maybe a cruise vessel. She thinks of buying an illustrated book about ships, all the different kinds. The ship slowly crosses the three picture windows, absorbing the afternoon. When her cell phone rings, once, then twice, she doesn’t answer it. You should have at least sketched the ship, she thinks, too late, as it passes from her last framed view. She gets up, rinses her unused brushes in naphtha in her bathroom sink, props them head-up in jars to dry. She scrapes the red from her knife, wipes it, sets her palette aside. The image of a ship, perfect in its wandering free, floating ship-ness. A floating seagull. Or the ocean itself, the view from your window, the waves and all that beautiful sky. A simple seascape. You should just paint whatever you see, at the moment, in the moment, to get you started. Set you on the path. Why don’t you just do that? Like a prompt. Yes, that’s what you’ll do. She rips from A Collector’s Guide to Seashells of the World several color plates of the more florid, exotic shells and scotch-tapes them, careful not to give herself paper cuts, over the framed photos of Nana Pearl’s family hung in groupings on the walls of her room.

The humming, relentless sound of breaking waves is beginning to get on her nerves. It is starting to feel as if two conch shells are clamped on her head, trapping the sea’s whispery rise and falls against her ears.

“IT IS ENJOYABLE for me to watch you cook,” says Bernadette with pleasure. “It is so different from Sri Lankan cooking.”

“Yeah, that’s true,” replies Sarah, unsure of what else to say. As she continues ribboning a roasted red pepper, Bernadette conscientiously snaps off the kitchen light.

“Could you leave that on?” Sarah asks politely. “I mean, I know it’s still pretty light out, but this is sort of a sharp knife.”

“Oh, yes, I am sorry.” Bernadette, lugging in the burlap bag of basmati rice, snaps the light back on. “You are having trouble with your eyes?”

“No, no, they’re fine. I’d just hate to cut myself, you know.”

“I have cataracts,” Bernadette informs her loudly. “Next month I am going home to Sri Lanka for the surgery.”

“Really?” I’ll have the house to myself, Sarah thinks. Good, easier to focus that way.

“And for my teeth, too.” Bernadette taps her upper lip with a finger. “I am losing so many teeth, here.”

“I’m sorry. Do you really have to fly back to do all of that?”

“It is less money for me at home.”

“Ah.” Sarah nods sympathetically. She feels reproachable for her sound teeth, her waste of light.

“But it will be good for visiting my family,” Bernadette says, measuring rice into a saucepan. “My daughter Nissa is graduating from school as a doctor.”

“That’s great. Congratulations. You must be really proud.”

“And my daughter Celeste has the new little boy I have not seen yet. It makes me lonely for him.”

“You must miss them,” Sarah says. How can someone be lonely for someone they’ve never met? she thinks.

“Yes,” Bernadette says cheerfully. “Very much. I will show you photographs?”

“Sure, yeah.”

“It is hard for a mother, when she is not with her children. Even when they are grown, and off living their own lives. But, perhaps it not as hard for the child?” She looks at Sarah, a small, closed-lipped, questioning smile that makes her nervous.

“Oh, I don’t know about that,” she says. “I miss my parents. I mean, of course I miss them. That’s totally normal, right?”

Bernadette adds a stream of cloudy water to her rice, sets the pan on the stove. “And how is your painting coming? It is happy for you, being here?”

“It’s great. I’m getting so much done. The open air, all the light. The quiet . . .”

“Avery and I were discussing this. We would love to see your work.”

“Well, that’s really nice of you guys, thank you, but—”

“But an artist must be ready to do this. It must be the right time, for showing the work to others. We understand.”

“Yeah. Exactly. But sometime, sure. Thanks.” She puts her knife down in the sink, scoops her red pepper on top of her pasta.

“Ah, you are having that on your noodles? I see.”

“Oh, let me get out of your way, now,” Sarah says quickly, taking her plate upstairs to her room.

THE HOUSE PHONE rings the next day as she’s slicing strawberries for her afternoon snack. After this, she thinks, you will take a good, vigorous walk on the beach, before that fog comes in. Get your blood moving. And then you will get to work. Get productive, take full advantage of this important—

“Hello?”

“Is this Sarah?”

“Yes?”

“It’s Marty. You know, Julius’s friend.”

“Oh. Hi.”

“I’m having shabbes dinner with friends tonight, they live down the street from you.”

“Uh huh.”

“It’s the last night of Passover, too.”

“Oh, yeah, that’s right. Damn, I forgot.” She suddenly pictures her parents, going through the motions of a seder without her, alone. A lonely lamb shank, two hard-boiled eggs. Store-bought gefilte fish, a sad, sodium-filled can of chicken soup. Waiting for her to call and check in, Happy Pesach, Mom and Dad! Or maybe they didn’t even bother having a seder this year, with her gone. She sees them sitting alone at the kitchen table, eating one of the low-fat casseroles she’d prepared, labeled, stocked their freezer with. She feels sad, guilty, the dull start of a headache, doesn’t hear the silence on the line, and then:

“Well, you want to come or what?” His voice is softer, freer of Brooklyn than Julius’s.

“Um . . . I’m just putting my dinner in the oven.”

“Take it out.”

She thinks of her greasy hair, her still-unwashed body. “What time?”

“Not till seven-thirty or eight. We’re still shooting. I’ll pick you up.”

“Okay. Not before seven-thirty,” she says, calculating.

“It’s shabbes, Sarah. We can’t eat before eight, anyway.”

He hangs up, and she figures if she cuts short her walk she’ll have plenty of time to shower and dress for dinner, to do her hair. She’ll come up with a new ritual to inspire the perfect painting. No more chocolate, maybe. Or no more wine, that’s good, be disciplined, keep your head clear, yes.

HE IS DRESSED nicely in black jeans and a linen shirt, his jaw shaved free of bristle, but still wears the black knit cap.

“We’re walking?” she asks, following him down the sidewalk.

“They only live a few blocks over. I walked here.”

They cross the main boulevard, away from the fancier oceanfront properties and the darkening eastern sky, wind through the neighborhood of modest homes pressing close to the street, children’s toys and aluminum lawn chairs left out on porches, bathing suits hung out to dry. They pass families walking along, on their way to synagogue, she assumes, from their yarmulkes and dark suits, the women dressed in long sleeves, long skirts, hats or fancy scarves covering their heads. Even the children, solemn and formally dressed, walking beside their parents like tiny sedate adults.

“So, who are these people? Where we’re going?”

“Itzak and Darlene, their kids. Itzak and I grew up together.”

“Like you and Julius?”

“No, I knew Julius later. Itzak and me, we used to steal Abba Zabbas from the dime store, you know? Cut school and go smoke grass. Sneak out to the city, go to the clubs. That was music. You ever hear of the Cedar Bar? The Village Vanguard?”

“No.”

“No? Wow. Early, mid-sixties, Itzak and me, we’re just kids, right? We’re maybe fifteen, sixteen, we’re sneaking into these basement clubs, we’re hearing Al Cohn, Howard Hart. Miles Davis. Wild.”

“I’ve heard of Miles Davis,” she says.

“Itzak’s Hasidic now. Really beautiful.”

“Oh?” Who is this person? she thinks. What am I doing here? “I feel funny, not bringing anything. I’m a bad guest.”

“You could’ve brought the wrong thing, though. Even the wine, it has to be kosher.”

“I thought of that. I would’ve brought a bag of oranges, or something.”

He shrugs. “Hey, whatever.”

She feels dismissed, somehow. Irrelevant. “So . . . when did you start keeping kosher? Julius said it was a new thing for you?”

“Couple of years ago.”

“Sort of a . . .” she is about to say midlife crisis, but stops herself, “. . . spiritual awakening?”

“I had stuff to figure out. Think about.”

“Looking for answers?”

“Looking for questions.” He smiles, nods at a young couple pushing a stroller. “Shabbat Shalom,” he tells them, and they smile, murmur back: “Chag Sameach.”

“See, that’s nice,” he says quietly to Sarah. “All the young people living here now. They’re moving back and settling down, starting their own families. We got all these kids growing up here together, the Jewish kids, the Irish and the Hispanic and black kids, they’re all out on the playground. The old people, they sit and watch. Everyone going to shul or church on Sunday morning. A real community. It’s beautiful. It’s got this energy, you know? When people come together like that.”

“It’s so different from where I grew up. Nobody talked to anybody. Everybody just drives around in their car.”

“So, this is good for you, yeah?”

“Oh sure,” she says. “You can really feel the energy here. Like you said.

He nods. She doesn’t know what else to say. They walk in silence, as she feels the fog limpen her hair.

ITZAK LOOKS LIKE an Old World photograph of someone’s dead great-grandfather, in blacks and beiges, elaborately yarmulke’d, with sepia-tinted teeth and long gray beard wispy as a cirrus cloud. The house is decorated with Judaica. Sarah expects his wife to be shrouded and bewigged and haggard from childbearing, but Darlene is trimly dressed in a sleeveless blouse and slacks, with her own curly bobbed hair. Their teenage son Jonah is wearing a Nine Inch Nails T-shirt, and joke-pleads with his father about the promise of a new videogame; their daughter Gwen, skinny and miniskirted, her right ear triple-pierced, is a freshman at NYU, studying psychology. They invite Sarah to sit in the place of honor and she readies herself, steels herself for the endless and obligatory ritual—Why matzoh? Why bitter herbs? Why do we recline?—but there is no wine-stained Haggadah in sight, no painstaking array of bitter herbs and chopped apple-and-nuts; the family simply sings in Hebrew one quick and ebullient prayer she doesn’t know, and Itzak announces That’s it, everybody, let’s eat!

Everyone troops happily to the kitchen sink to wash their hands. Back at the table Itzak passes her a plate of matzoh and she readies herself again, for the hurrying-from-bondage-and-Pharaoh’s-troops lecture (lamb’s blood smeared on doors, gross), the ten plagues that always creeped her out as a child (pestilence, boils, locusts, darkness and tragedy and despair to be visited upon their house at any moment), but Itzak’s discussion of matzoh is Freudian: The unleavened bread, he says, symbolizes the suppression of human ego. Risen bread, puffed up with yeast and air, shows the swelling of ego, the human soul presumptuous before God. Gwen proclaims all religious ecstasy—any type of religious faith, she argues, actually—to be merely a form of psychological repression if not outright delusion, which Jonah—apparently planning on rabbinical school—takes good-natured issue with, and as the debate continues and floats over her head and beyond her, Sarah quickly drinks down the glass of kosher wine Itzak has poured for her—an exception to the rule, but she’s never tasted kosher wine, is curious, although there is no discernible difference in taste from regular wine, she thinks—then is too embarrassed to ask for more. Always plenty of wine, at home, at least. The Kiddush, the blessing of the wine, fill that cup again, by all means.