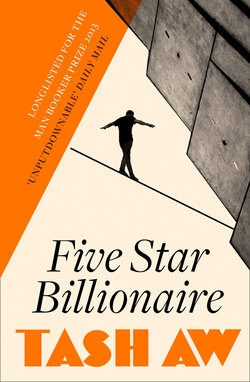

Читать книгу Five Star Billionaire - Tash Aw - Страница 17

How to Manage Time

ОглавлениеWhen I was thirteen, I was sent away to live with relatives in the far south of Malaysia, at the opposite end of the country from where I had been born. Do not be alarmed – this sort of displacement is quite normal amongst underprivileged rural families. My mother had died a few years previously and my father, unable to care for me properly, decided to ask my great-aunt to take me in. He himself had to move away from our village to seek work in Kota Bharu, where he lived in one room above a tyre repair shop. It made sense for him to be free of me.

My great-aunt lived and worked on a small pineapple farm about thirty miles north of Singapore. The peaty soil of the region was famous for producing the best pineapples in the country, but ours were an exception to the rule, being meagre in size and acidic in taste. Nothing I did seemed to improve them – not the addition of buffalo manure or even the chemical fertilisers I found on a lorry parked by the road one day (there was no one about, and far too much fertiliser for any one person to use, so I helped myself). Even at that age I found the lack of a satisfactory solution very frustrating. Why couldn’t I make those pineapples big and sweet? I worked on the farm every day after school – it was my way of earning my keep and it kept me out of mischief, said my great-aunt. I do not have fond memories of this period, because it involved failure: the only failure I have encountered in my life thus far. To this day, even a brief encounter with hard, unripe pineapple (of the kind one routinely encounters on aeroplanes) is enough to send me into quite a rage.

Life in the south was not a thing of beauty. The landscape lacked the soul of the north, the wilderness, the poetry. It is surprising how one’s childhood days can be troubled by the finer concerns of the spirit, filled as they are with the anxieties of youth. I was picked on at school, teased for my accent, which I was never fully able to lose – the unconscious warping of ‘a’s to ‘e’s or ‘o’s, the dropping of the ends of words, the addition of unfamiliar emphatic exclamations. My speech marked me out as foreign and, unsurprisingly, I became known as a quiet boy who said very little. I spent much time lurking in the background, so to speak, watching from the sidelines and never thrusting myself into the spotlight. By remaining in the shadows I learnt to observe the workings of the human psyche – what people want and how they get it. Everything that I was to achieve later in life can be traced back to this period, when I began my apprenticeship in the art of survival.

All that earnest study of the cut and thrust of life meant that I did not have time to miss home. I did not suffer from any longing for my homeland in the north, with its strange, warm dialect and its melancholy coastline scarred with brackish streams that ebbed and flowed with the tide. It is only now that I have the luxury of time and rich personal accomplishment that I can sit back and appreciate a certain sentiment for the village in which I grew up. This does not, however, mean that I am someone prone to nostalgia. I am certainly not encumbered by the past.

Like most people in our position, we lived an industrious but precarious existence. My great-aunt had worked part-time in a factory on the outskirts of Johor Baru that produced VHS players for export, but, being in her fifties, she was soon laid off and had no work other than to tend to our smallholding, and we were therefore forced to be inventive in the way we made our living. Nowadays I hear liberal, educated people refer sympathetically to such a way of life as ‘hard’, or even ‘desperate’, but I prefer to think of it as creative. I had just turned thirteen, and thought that if we had more money I would be able to return home.

I began selling pineapples on a disused wooden stand by the side of the road that led to the coast, hoping to ensnare day-trippers from Singapore on their way to Desaru. Knowing that our pineapples were sour, I sold them cheaply, and in the first few weeks I managed to make a little money. But even this began to dry up as people realised the low quality of my wares. So one day I bought a supersweet pineapple in the market and cut it up in pieces, offering it as proof of my own fruit’s tenderness. A number of people fell for it, and only one couple complained on their way back from the coast. I feigned innocence – I couldn’t guarantee that every pineapple would be sweet. They showed me a pineapple cut in half, and I recognised its dry, pale flesh as one of mine. They insisted I give them five pineapples for free, and when I refused, the woman called me names and her companion ended up hurling the pineapple at my head. I ducked but it caught me on my ear, making it swell like a mushroom. Soon afterwards I abandoned the stall and got a job waiting tables at a local coffee shop.

I did not see my father for nearly four years. I received news from him occasionally, when a letter would arrive via my great-aunt. He would write about the Kelantan river bursting its banks in the monsoon season, the kite-flying contests that year, the second-hand scooter he had bought, things he had eaten in the market – uninteresting news of daily life. Once he told me he had bought me a large spinning top which awaited my return, but when I finally went home there was no further mention of it.

There was never any news of jobs or money – the very reason we had to move away from home. There was no indication of how he was planning our future, no sense that he was aware of the passage of time. I had never been aware of this myself, but now, hundreds of miles from home, I could almost hear the seconds of an invisible clock ticking away in my head. I had gone to live with my great-aunt thinking that it was temporary, and that I would be back home as soon as my father ‘got settled’. That was what he told me. After a year I realised that my residence in the dull flatlands of the south was not going to be as fleeting as I had hoped. One learns quickly at that age. Like all children, I had never before appreciated what time meant – the years stretched infinitely beyond me, waiting, impossibly, to be filled. But all of a sudden I began to feel the urgency of each day. I counted them down, saddened by how much I could have been doing with every sunrise and sunset, if only I had been at home.

I waited for my father to think of a plan that would reunite us in our village, but, incapable of understanding that time was not on his side, he left me waiting.

You must appreciate that time is always against you. It is never kind or encouraging. It gnaws away invisibly at all good things. Therefore, if you have any desire to accomplish anything, even the simplest task, do it swiftly and with great purpose, or time will drag it away from you.

Four years. They passed so quickly.