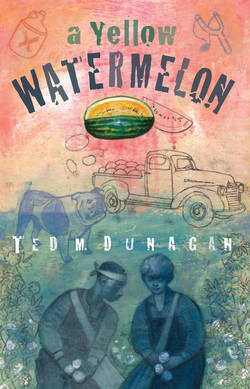

Читать книгу A Yellow Watermelon - Ted Dunagan - Страница 10

4 Nail Soup

ОглавлениеI dashed into the woods just past Miss Lena’s store. When I reached the first pile of logs, not yet in sight of Jake’s shack, I stopped dead in my tracks. I heard a strange, rhythmic, melodious, wonderful sound—one I had never heard before, and I liked it.

The sound stopped. I stood frozen in my spot and waited for it to start again. It didn’t, so I walked on past the far end of the sawmill and there was Jake, sitting on a block of wood, staring into his bed of hot coals with his old guitar resting across his knees.

He looked up at that moment and I said, “Hello, Jake.”

“Ted! Well, now, don’t you look nice. You been to church?”

“Yeah, we had dinner-on-the-grounds today.”

“Been a long time since I been to one of dem, but I remember all dat fine food. I was just getting ready to fry me up a couple of flapjacks. I ’spect you too full to join me.”

“Yeah, I’m stuffed. But I brought you a couple of pieces of fried chicken to go with your flapjacks.”

“Lawd have mercy,” Jake said as he unfolded the wax paper. “You be Mister Ted from now on. Bless yore little heart, Mister Ted. Why you do dis?”

I wanted to tell him that I had always been taught to offer a gift if you wanted something, and I did want something from him. I wanted answers, but I didn’t know how to explain this, so I just said, “I don’t know. Just saw all that food and thought you might like some.”

“You mind if I go ahead and eat dis chicken? Dem flapjacks can wait.”

“No. Go ahead.”

I watched while Jake ate his chicken, threw the bones into the fire, then wiped his hands on his handkerchief. Only then did I feel it was appropriate to question him. But the questions the preacher had raised could wait, because I had to know about the music. “Jake, you were playing your guitar and singing before I got here, weren’t you?”

“I sho was. You heard me?”

“I sure did.”

“You like it?”

“I liked it very much, but I never heard anything like it before. What kind of music was it?”

“Why, dem wuz de blues. I wuz singing de blues.”

“What in the world is the blues?”

“Well, now, dat’s kinda hard to explain, but I goings to try. De blues is something deeper dan a mood. It—it comes from heartache caused by want, need, hurt, loss, hard work, sacrifices, and things like dat.”

“Why would you want to sing about stuff like that?”

“You just full of questions today, and dat’s another tough one. I s’pose singing de blues kind of makes dose things not seem quite so bad, plus it’s a reminder that they do exist.”

“Can just black folks sing the blues?”

“Shoot no. White folks can sing ’em too. I’ve heard ’em do it.”

“Where do the songs come from?”

“I just makes ’em up as I go along.”

“How in the world do you do that?”

“I be happy to show you. Dis’ll be yo’ song. You just pick out a subject.”

“I don’t know how to do that.”

“Sho you do. Pick out something like being hungry with no food, some kind of hard work, or—”

“How about this old sawmill?” I interrupted.

“Oh yeah, dat’s easy.”

I watched while Jake started strumming on his guitar, then suddenly he picked up the pace and broke into song:

“Got dem old sawmill blues

“De kind you just can’t lose

“Got sawdust in my clothes

“Got sawdust in my nose

“Sweat all in my eyes

“I ain’t telling no lies

“No time to drink no booze

“’Cause I got dem old sawmill blues . . .”

I sat there on that block of wood and was completely captured by the essence of the words, the sounds of the instrument and Jake’s voice. It was as if I could actually feel the music, an experience I had never had before. He went through the song four times and I had it memorized by the time he hit his last chord on his guitar. The sound and the wonder of the music lingered in my memory, and I was still tapping my toe, even after it was over.

We moved away from the heat of the sun and hot coals onto a bench in a spot of shade beside Jake’s shack. The bench was simply a scrap board resting on two more blocks of wood.

We sat in silence for a few moments before Jake said, “You got something else besides de blues on yo’ mind, don’t you?”

“Yeah, how you know?”

“You just quiet and thoughtful looking.”

I felt awkward and knew even at my young age that I was broaching a sensitive subject, but somehow I knew Jake would understand and explain things to me. I started slowly, reached a comfort level, then proceeded to tell him the entire story about the last part of the preacher’s sermon.

When I finished, once again, we sat in silence for a while until Jake asked, “So what you think about what yo’ preacher said?”

I had been waiting for him to tell me what he thought. Now he was asking me, so I told him. “I ain’t too sure that preacher was right at all.”

“You can bet yo’ bottom dollar on dat. He was right by saying a mark was put on Cain and he wuz sent off to de Land of Nod. But de next time you see dat preacher, tell him to read further and de Bible will say dat Cain and his family went on to be folks who lived in tents and raised livestock. Don’t sound like black folks to me. He just trying to stir up some hate. Proud to see it didn’t work on you.”

“You read the Bible?”

“Read it from cover to cover.”

“When did you do that?”

“When I was in de— While back when I had a little time on my hands.”

“How about that word, the one y’all don’t like to be called?” I didn’t want to say it.

“You means, nigger?”

“Yeah.”

“What about it?’

“Where did it come from and how come y’all don’t like it?”

“It come from back in the slave times when ignorant folks couldn’t pronounce Negro. I s’pose we don’t like it ’cause it reminds us of dat part of our past. Now, anything else bothering you today?”

Jake had awakened the music in my soul, erased the doubts in my mind, and added to my education that day. I still wasn’t sure what that preacher was up to. It was as if he had been preaching to Old Man Cliff Creel. I would have to ponder on that.

In the meantime, there was one more thing bothering me about Jake. “You ain’t got no garden and no chickens. You can’t live on flapjacks. What else do you eat?”

“I went to Miz Miss Lena’s after you left yesterday and bought myself some groceries.”

“What’d you buy?”

“I got me some tins of sardines, a few cans of pork ’n beans, box of soda crackers, sack of flour, and a bucket of lard.”

“My mother says you can’t live on stuff like that. You need fresh fruit and vegetables, eggs, and occasionally a piece of meat.”

“She absolutely right. Eggs is what I miss most. Dey would go mighty fine with my flapjacks in the mornings. But if worst comes to worst, I can always make myself some nail soup.”

“Nail soup—what in the world is that?”

“You never heard de story ’bout nail soup?”

“No, never did. Will you tell me?”

“I sho will. Can’t rightly say whether I read it or somebody told it to me, but it goes like dis:

“Dey was a gentlemen traveling by foot down a lonely road. It came on toward dinner time and a powerful hunger came upon him. A little farther down de road he came up on a farm house and dey was a lady in de front yard raking leaves. He decided to ask her for some food. Stopping at the front yard gate he spoke saying, ‘Top of the day to you, ma’am. I been traveling all day, I’m real hungry, and wondered if you might be able to spare a little food.’

“The woman replied, ‘I’m hungry myself, but I don’t have a scrap of food in the whole house.’

“De traveler said, ‘Well, in dat case, maybe I can help you. Do you happen to have some water and a cooking pot?’

“‘Why, yes, I do.’

“Reaching into his pocket, de traveler pulled out a shiny nail and said, ‘I have a magic nail here. If we put it into a pot of boiling water it will make a fine soup, den we both can eat.’

“‘Do tell,’ the lady said. ‘Come on in the house and let’s put a pot of water on the fire.’

“Once the water was boiling the traveler dropped the nail in the pot and said, ‘Now, pretty soon we’ll have us a fine bowl of soup, but, you know, if we just had a potato, den de soup would be outstanding.’

“Whereupon the lady said, ‘Well, I do happen to have just one potato in my pantry.’

“After adding the potato to the pot the traveler proclaimed, ‘Yes, ma’am, dis soup gon’ be mighty good, but, you know, if we just had a piece of meat, den it would be delicious.’

“The lady jumped to her feet and said, ‘Guess what, I do have one small piece of meat.’

“A little while later while dey both were sitting at the table enjoying de soup de lady said, ‘This is some very good soup. And just think, we made it from nothing but water and a magic nail.’”

Jake stopped talking and I realized the story was over. I also figured there was some kind of hidden meaning in it and he was waiting for me to tell him what I thought it was.

My feelings were confirmed when he asked, “All right, Mister Ted, what do you think dat story means?”

“That people hide their food?”

Jake chuckled and said, “Dat too, but something more—think about it some.”

I did, and then said, “The traveler tricked the lady into giving him some food?”

“Yes he did, but then he shared it with the lady. The main point is dat a smart man, a resourceful man, can always figure out a way to find hisself a bite to eat. So, don’t you be worrying about old Jake, ’cause I’ll be all right.”

I wanted to spend more time with Jake, but I knew it was getting on toward midafternoon. Pretty soon my cousin Robert would be driving my mother and Fred home. If they found me on the road I’d have to explain where I had been, so I said good-bye to Jake, sneaked through the woods, and started walking toward home.

My father hadn’t seen me coming down the road. He was on the front porch skinning squirrels and singing a mournful sounding song. I heard two lines of the tune before he saw me. It went like this:

“All around the water tank

“Just waiting for the train . . .”

When he saw me he stopped singing and asked, “Where’s your mother and your brother?”

“They’re visiting Uncle Curtis. I wanted to come on home and see if you got a turkey.”

“Naw, I saw a big old gobbler, but I wasn’t able to call him up. He outsmarted me today, but I’ll get him sooner or later.”

I had been turkey hunting with him before. He would scrape a piece of slate across a small wooden box he had made out of cedar, imitating the sound of a hen turkey, drawing the gobbler in close enough for the kill with his shotgun. All the while you had to sit hidden and motionless for a very long time, ignoring the bug bites and cramps. Then the sudden blast of the shotgun would make me just about jump out of my skin. Still, it was better than going to church. He always cut the beards off the big birds and gave them to me. I kept them in a cigar box underneath my bed. “What’s that song you were singing about?”

“Oh, it’s about a man, a hobo, hanging around the water tank beside the railroad track because he knows the train will stop there. While it’s stopped he’s gonna sneak into a box car and travel on down the line to some place where he might find some kind of work.”

Jake was right! White folks could sing the blues. My father had just been singing them and didn’t even know it.

He kept dressing those squirrels while he talked. I looked into the pan of murky water and saw six skinned and gutted carcasses floating there. I knew that later my mother would cut them up with her butcher knife, roll them in flour, drop them into hot grease, and fry them up crispy and brown. Then she would make the gravy and drop the fried pieces of squirrel into it. While it bubbled away on the stove, she would bake the big biscuits. Eventually we would burst them open, cover them with gravy, and eat them with the fried squirrel. I liked the back legs. It wasn’t turkey, but squirrel was good.

“Where’s Ned?” I asked, while following my father from the front porch to the kitchen.

He set the pan containing our dinner on the table and answered, “He’s gone back in the woods with a bucket. He found a honey tree and he’s gone back to rob it.”

My brother Ned was good at finding a honey tree, which was a hollow tree with a wild bee hive inside it. The bees gathered pollen from the wild flowers in the woods and the fields, resulting in the production of the most delectable honey to ever touch your mouth. I know how he captured the honey—I had been with him when he did it. He would build a small fire around the tree, throw some wet leaves on the fire, and the smoke would drive the bees away. While they were away he would scoop the honeycombs out with his hands, deposit them into a bucket and be gone before the bees returned. He never got stung and always brought home the honey.

Today was no exception. After a while I saw him emerging from the edge of the woods lugging a five-gallon bucket, which he set on the front porch. He was smoky and sticky, so I dipped water into the wash pan for him. While he was washing up he said to me, “Taste and see if it is good and sweet.”

I dug my hand into the bucket, tore off a piece of honeycomb and stuffed into my mouth, and started chewing. My mouth was a flower garden. I chewed until there was nothing left but a hunk of wax, which I spat out in the yard.

“Well?” Ned asked.

“It’s great,” I said, licking my fingers.

Later my mother squeezed the honey from the combs and had six quarts of golden liquid on the table at supper time. Besides the squirrel gravy on the biscuits, we also had the nectar of the gods, thanks to my brother Ned, the bee hunter.

After supper, as we were all sitting around the table, my mother asked, “Well, how was everything?”

I said, “It was a lot better than nail soup,” then I got up and left the table with everyone staring at me.