Читать книгу Different . . . Not Less - Temple Grandin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHARLI DEVNET, BA, MA, JD

Age: 57

Resides in: Croton-on-Hudson, NY

Occupation: Tour guide and legal freelancer

Marital status: Single

FROM TEMPLE:

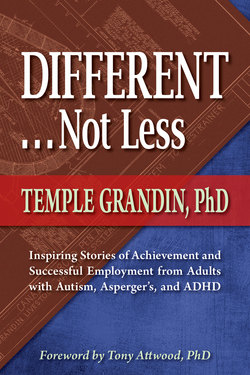

I chose Charli as the first Different…Not Less story because I know her insightful cover letter will offer hope to so many people on the spectrum. After years of struggle and a series of false starts, Charli found positive direction in life through an unusual job that was right for her. Charli’s chapter begins with her cover letter, explaining why she would be a good candidate for inclusion in this book.

CHARLI’S INTRODUCTION

Despite my seemingly satisfactory verbal skills, I have been significantly challenged by autism. I know many adults have received a diagnosis of some form of autism, yet—in my eyes—they have such a mild level of impairment that they seem to be able to lead fairly normal lives. Any one of them could provide you with a more conventional career success story. When I first heard about Temple’s new book, I was afraid it would only relate the stories of higher-functioning individuals and that those of us who have struggled with near-insurmountable difficulties just to achieve a measure of acceptance in our personal and professional lives would be overlooked. I believe that those of us who are not in the “near-normal” category should also have a voice. Feel free to use my name. I am not ashamed of who I am—not any longer.

For the past 10 years, I have worked at a historical house museum, called “Kykuit,” in Sleepy Hollow, New York. Kykuit was formerly the countryseat of the Rockefeller family. I work as a tour guide and, on Saturdays, I sell memberships for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the present landlord of Kykuit. The name “Kykuit” is a Dutch word, meaning “lookout” or “high place.” When the Dutch settled along the banks of the Hudson River back in the 17th century, they assigned the name to a craggy, rocky hilltop 500 feet above sea level. This hilltop was used by the local Indian tribes as a signal post. Now, 500 feet may not seem very high to those who live in Colorado, but here in Westchester Country, it almost touches the sky! A hundred years ago, the richest family in America transformed this barren, rocky hilltop into a little bit of paradise.

This is the best job I have ever had. I love my work for so many reasons. First of all, the site itself is both peaceful and inspiring. Sculpted on the façade of the house are two classical deities, joined together by a laurel branch—Apollo, who represents culture, art, and science, and Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and harvest. Art and nature work in harmony to create a place of wonder—the sweeping views of the Hudson and the Palisades take your breath away, enhanced by the sculpture gardens, fountains, and greenery. The house itself is interesting, but it’s the exteriors that are a treasure. John D. Rockefeller, Sr, the oil baron, was a robust, outdoorsy, athletic type of man. Despite his vast wealth, he cared nothing for high society or manmade opulence—he was a Baptist and preferred to spend his money, if he must spend it, on the gardens, golf course, and woodlands.

Sense of Camaraderie with Tour Guides

My colleagues at Kykuit have provided me with a sense of camaraderie that I have not known since junior-high school. The other guides are all intelligent and highly educated, with diverse backgrounds. Some are retired teachers, and some have a background in the arts. A few, like me, have worked in the legal field. Now, I myself am intelligent and educated, and those qualities alone would never impress me. However, the other guides embody the attributes that are lacking in me, which I therefore admire in other people—attributes like poise, sophistication, self-assurance, and possession of the social graces. They generally consider themselves “artsy,” and, as such, feel almost obligated to be tolerant of the quirks and eccentricities of others and have therefore been more accepting of me than coworkers in the legal or business world might be. However, this was not always the case. At first, in my eagerness to become one of the “troupe,” I made comments that seemed witty and incisive to me but may well have been perceived as offensive, rude, and gauche. As time went by and we became better acquainted, we began to get on much better. If I did not find any close friends among my colleagues, at least we became friendly. On occasion, we get together outside of work for a field trip to a museum or other attraction. A few years ago, there was a public art “happening” in Central Park, called “The Gates,” and the guides all went down together. While I might have gone alone, it was much more fun going with the gang from work.

One of the best aspects of my job is that it allows me to talk and be the center of attention. For two and a quarter hours, visitors must follow me around and listen to me speak about matters in which I am interested and knowledgeable. They cannot change the subject and have a conversation in which I can take no part—about their children or their mortgages or where they are going on vacation—nor can they just talk over me as if I were not there.

What I like best about being a tour guide is actually the greatest obstacle to retaining the job. While the wages are low, the job actually requires a high-level skill set. It requires knowledge of both American history and art history (which fall right in my area of special interest). I have always had a keen interest in history and politics, so for any aspects of the material of which I knew nothing—for example, modern art, styles of architecture, and landscaping theory—I quickly picked them up. In fact, I enjoyed having new subjects to delve into. However, a guide also has to be comfortable with public speaking, which presented me with a great challenge. My first season was almost my last. Sure, I could talk on and on—but does anyone want to listen? My presentation was where I ran into trouble. In my first year, I was criticized for speaking in monotone, not looking visitors in the eye, not projecting my voice, having a “flat affect,” and being consistently late to the bus at the end of the tour. I came very close to losing my job, as I had lost many others before it.

Developing Confidence

During that first summer, however, my beautiful mother died at the age of 74, from smoking-related lung cancer. Her loss threatened to send me into a serious tailspin. I adored my mother. She may not have been the most nurturing or supportive of parents, as she had difficulty expressing her emotions—but I loved her. Despite the fact that she smoked, she had always taken good care of herself, and I had thought she would die well into her 90s, if at all. Because of my mother’s death, I needed the structure and the socialization that my job at Kykuit provided, and I acquired the social skills that were necessary to keep it. I discovered in myself abilities that had lain dormant all my life—abilities that few autistic people ever get a chance to develop: the self-Confidence to speak in public, to be articulate and to modulate my voice, to make witty comments that are amusing to everyone (and not just to myself), and to impart my knowledge in a way that holds a visitor’s interest and attention. Problems remain in abiding by the schedule and making it to the bus on time, but the other guides know I have this tendency, and they hurry me along.

When talking about career success, if you’re referring to fame and fortune, a fat paycheck, a position of power, or a world-shattering discovery, I have nothing to offer. However, what I am able to impart is a story about a low-paying, seasonal, offbeat job that has made me very happy, provided me with a touchstone through years of loss and personal tragedy, and given me an opportunity to develop many interpersonal and social skills that I never dreamed I could possess.

Mid-40s Subsistence Living

Although I have several advanced degrees, I have spent most of my adult life either unemployed or underemployed. By my mid-40s, I had learned to eke out a subsistence living by putting together a patchwork of part-time, low-paying jobs, all of which I was overqualified for. I understand this is a common pattern with Aspies. At the time, however, I had not received a formal diagnosis. To my mind—and the minds of others around me—I was simply a disappointment, a failure, and an underachiever—a “no-good, lazy bum” who did not try hard enough. As a child in the 1960s, I had been tagged as being “emotionally immature,” and that label stuck well into midlife. Then I saw an ad for tour guides at Kykuit. I’ve had this job for 10 years now, and it has quite literally saved my life during my darkest days.

Feeling of Empowerment from Diagnosis

Three years after losing my mother, my dad also passed away. Two years ago, I lost the elderly aunt who had rescued me when I was a totally dysfunctional person in my early 20s. She had given me a home for 30 years, and when she died, I was so paralyzed with depression and anxiety that I contemplated suicide. In the end, I sought therapy and received a diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome with anxiety and depression. My diagnosis has given me a feeling of empowerment. Finally knowing what was “wrong” with me allowed me to embark on a belated but liberating journey of self-discovery. Through it all, my job as a tour guide at Kykuit has provided me with solace, purpose, and, at times, the only social life I had. It has also given me the chance to shine. Today, guests often compliment me—sometimes to management—on what a knowledgeable, funny, and articulate tour guide I am. Although few people in the neuto-rypical world would consider my story indicative of professional success, the personal level of success and fulfillment I have found is invaluable.

MY STORY

To look at me now, you might never know I have spent my life living in a world of strangers.

Until the summer I turned 13, I was a rather high-functioning child in the small riverside village of Croton-on-Hudson, New York. My mother was beautiful, intelligent, glamorous, and aloof. I adored her. She had difficulty displaying her emotions, but it was probably not her fault. Her own father, for whom I am named, was just like her—handsome, taciturn, and remote—a “refrigerator grandpa.” I adored him, too, but he never let me get close. My mother’s name was Jacqueline, like the First Lady, whom she did indeed look like. In fact, the resemblance was so strong that when Jackie Onassis died, I felt pangs of grief, although my own mom was alive and well at the time.

My Parents

My mother claimed that, as a child, her family had been wealthy and lived in a big house on a hill, with a maid. I discovered later this was indeed true. Grandpa Charlie had once been a big wheel in the local restaurant business and probably a former bootlegger, as well. By the time I was born, however, my grandparents were anything but rich. They operated a bar and grill two blocks from Sing Sing Prison in the neighboring village of Ossining. We called it “The Saloon,” but it was no honky-tonk—just an everyday bar and grill where the correctional officers hung out between shifts. Nevertheless, my mom always carried herself like a displaced aristocrat.

You would think that, given her obsession with lost wealth and status, she would have married “up,” but the opposite was true. She wed her childhood sweetheart, the eighth of ten children of an Italian stonemason, all as poor as could be.

My dad was the polar opposite of my mom: warm, loving, easygoing, and thoroughly neurotypical. At the age of 17, he had quit high school and gone off to fight with the marines in World War II. He almost drowned at Okinawa, but fortunately he survived to return to his hometown and marry his childhood sweetheart, whom, like me, he regarded with absolute awe. Despite his good nature, my dad had very few parenting skills. Perhaps he was so disappointed I was not the daughter he had expected and longed for that he kept me at bay. Perhaps, as I began to suspect many years later, the horrendous events he had seen at places like Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and Nagasaki never really left him.

A Tomboy Best Friend

That my parents were not the best nurturers in the world mattered little at first. I had two sets of grandparents and a plethora of aunts and uncles within a few miles’ radius to take up the slack. There were also plenty of other kids—our neighborhood was literally crawling with children my own age or near to it, as it was the height of the baby boom. I even had a best friend—golden-haired Alexis, who lived next door. She was a tomboy, like me, but she was built like a pixie. I spent a lot of time at her house, at the homes of other playmates, and out on the street in pickup games with the other kids. Sure, I was a bit of a misfit, but I was not lonely—at least, not then.

My mom knew I was different, but she believed I was different in the best of ways. She thought I was a near-genius. The evidence for this was not overwhelming, but I could read fairly well by the age of four, and shortly thereafter I came up with interesting but useless facts, such as the capital cities of every state, all the kings and queens of England, and the gods of Mount Olympus. My mother was certain she had a precocious little sage on her hands.

SCHOOL YEARS

Unkind Treatment by Teachers and Classmates

My troubles began when I started school, and I received unkind treatment by both teachers and classmates. I recall being sent to a speech therapist, but my teachers did not see me as being impaired—they viewed me as a gifted child with a behavioral problem, and they came down on me harshly. Such a bright child as myself should have known better than to misbehave so consistently. I did know better, and I misbehaved anyway. I did not mean to do so, and sometimes I didn’t even realize I had misbehaved until I found myself cooling my heels in the principal’s office. Especially in the early grades, the schoolwork did not engage me, which led to trouble. In my view, my mom had done me no favors by teaching me to read as a toddler. What was I supposed to do in the 1st grade, when the rest of the class struggled to learn the letters of the alphabet? What could I do but goof off, cut up, and act out to relieve my boredom? It was the practice of the time for scholastically advanced students to be allowed to skip a grade, but I was never permitted that option because I was “emotionally immature.”

The difficulties I had with other kids were even more worrisome. At least I knew what the teachers expected of me. Although I did have friends of my own, most of my classmates treated me like a misfit. Some of them were schoolyard bullies, who seem to have an unwavering instinct for targeting children who fall short of societal norms. They chased me down the street and tried to steal my books and throw them in the mud. Others mocked and made fun of me, and I was never really sure why. Perhaps I talked a bit funny, and perhaps I really did walk like a swaying ship, as my classmates said. Perhaps it was my many food aversions, which made me an extremely picky eater—a circumstance which some found amusing.

I consulted my mother. She advised me that the other children were all jealous of me because I was so highly intelligent. I doubted the soundness of her opinion. In my eyes, I was not particularly bright or gifted. Anyone could open up a book or study a map and learn things. Where was the magic in that? I admired children who possessed skills that I coveted but entirely lacked—those who could turn perfect cartwheels, keep a Hula-Hoop up on their waist, or make sculptures with papier-mâché. At the age of 7, I was the last kid on the block to take the training wheels off my bike and learn to keep my balance. In many ways, I felt like a first-class dummy.

Life Is Not Meant to Be a Bowl of Cherries

Despite these challenges, I rather enjoyed elementary school. Back then, kids seemed to understand that life was not meant to be a bowl of cherries. All of us expected to get some bruised knees and hurt feelings at times, and we all had battles to fight. Some students could not keep up their grades, and others could not play sports. Some were called names because they were too fat or too skinny. Some were Jewish and got no presents at Christmas. Eventually, I learned to stand my ground and ward off the bullies. I tamped down my urge to misbehave, which appeased my teachers.

I also benefited from the freedom that was granted to youngsters back then. Our parents did not expect to know where we were every hour of the day. We left in the morning and came home for dinner. If I was on the outs with the other kids, I did not have to stick around, nor did I have to run home and hide. I could hop on my bike and pedal across town to the home of a relative who would listen sympathetically. Or, I could go to the public library, where I could lose myself in stacks of tantalizingly unread books. I could go to the sweet shop, get a soda, and read the comics—or, I could simply ride down an unfamiliar street and explore.

My favorite subjects in school were history, geography, and social studies. The other kids hated history, and I wondered why. To me, history was full of wonderful stories, and I could easily recall names, dates, and places.

I also had a bent toward theology. My parents did one good thing for me—they made sure I had a religious background. Both my parents had been raised Roman Catholic. Dad had lost his faith somewhere along the way, probably during the war in Japan, but Mom was more steadfast. She rarely went to church herself. However, she made sure I went and attended catechism class on Thursday afternoons at the local catholic school.

When I was small, I became aware that having no siblings made me different. One day in 1st-grade art class, the teacher told us to draw pictures of our siblings. The other two “only children” in the class submitted pictures of their pets. I had neither sibling nor pet and had nothing to draw. After school, I ran home and angrily confronted my mother. Why had she made me such a weirdo? Why didn’t I have a brother or sister, like “normal” kids did? To my surprise and delight, she replied that it was indeed a good idea and that she would think about it.

As it happened, a few months later, my mother presented me with my very own brother. I was ecstatic. A little pal! A second in my corner! Someone to talk to when everyone else deserted me! I proudly took his baby pictures to school for “show and tell” and declared that I now had a “real” family, just like everyone else.

My Younger Brother Was Unlike Me

Unfortunately, the promise of a baby brother turned out differently than I’d hoped. At first, all went according to plan. He dutifully toddled around the house after me, calling me “Yar-Yar” in an attempt to say my name, “Charli.” As he grew older, however, he treated me with complete indifference. All my life, I have grieved the loss of the brother and pal I wanted and expected. In his place stood the perfect stranger.

My brother could not be more unlike me. He is quiet and shy, sensitive and withdrawn—a natural introvert. His one lifelong obsession has been music. As a tot, he drove us all crazy with his constant repetition of television commercials. As a child, he raided my record collection with seeming impunity. I cannot recall whether he had friends in school, but by college, he had fallen in with some musically inclined students, and his life improved. All his friends are musicians. As an adult, he became a music writer and even published two books on rock music. Like me, he has never married, but he has had a proper series of live-in girlfriends. If fame and fortune are the standards by which to judge “success,” then my brother had the career success in the family. However, I do not believe it brought him much long-lasting happiness or self-fulfillment. He has been out of work for some time now and fears that, at 50, he is washed up.

My brother is so dissimilar from me that, even when I began to suspect that I might be on the autism spectrum, it never occurred to me that he may be, as well. Two years ago, when I received a formal diagnosis, my psychiatrist gave me books on Asperger’s syndrome. One of the books indicated that autism runs in families. A light went on in my head, and I immediately telephoned my brother. However, a lifetime of misunderstanding is not easily overcome.

Seventh grade was the best year of my life. Junior high brought a greater variety of class work, and advanced courses were available in my favorite subjects. I took violin and played in the school orchestra. I played sports the other girls played—floor hockey and softball. I was fairly good, despite some deficits in motor skills. Both the disciplinary problems and the bullies were behind me. I even went to dances and began looking at boys. It seemed that I had finally conquered whatever-it-was that had kept me from fitting in. Just to be certain, I consulted my guidance counselor. “Do you think there is anything wrong with me?” I asked him. “Not at all,” he replied. “You seem like a typical 12-year-old to me.” I beamed in satisfaction.

My World Came Crashing Down When I Was Uprooted from My School and Friends

Unfortunately, my world soon came crashing down. The summer I turned 13, my parents purchased a crumbling old estate further up the Hudson, in the middle of nowhere. I was uprooted from my home, my school, and my friends—life as I knew it was over. I had no one to talk to, nothing to do, and no place to go. I mean no one. There were no neighbors. There were no kids my age around, nor even any grown-ups. My brother had already locked me out of his world. Aunts and uncles came up to see us at first, but my mother did not encourage visitors, and gradually I lost touch with my relatives. The nearest village was 3 miles away, and although I soon learned to bike there and haunt the small public library, the icy fingers of deep loneliness reached into my heart and paralyzed me. I foundered. I regressed and fell apart. As B.J. Thomas sang, “I’m so lonesome, I could die.” He could have been singing about me.

For the most part, my parents did not understand what was happening as their little savant shattered into pieces. My mother believed that it was all make-believe and that I was pretending to be abnormal to punish my parents for tearing me away from my friends and my hometown. My father was convinced that my breakdown was physical in nature, and indeed I showed physical signs of distress. I had begun my menses 6 months before we left Croton. Once we moved, they stopped entirely. As a child, I had always been one of the tallest kids in my class. By 7th grade, I had attained my full height of 5 feet 4 inches and never grew a smidgeon more. My dad believed it was an indication of some unspecified illness.

Unbearable Loneliness in a Big High School

Eventually, I was sent back to school, but that did nothing to alleviate my unbearable loneliness. The high school I attended was a modern, sterile, overcrowded facility to which teenagers were bussed from surrounding towns. The teachers were too busy to devote personal attention to any one student. I made no new friends to replace those I had left behind. The necessity of riding the school bus seemed a humiliation. In Croton, school buses were associated only with the very youngest children and those who lived out in the sticks. After 3rd grade, you walked or biked to school. Bullies reappeared in my life. These bullies did not chase me around the schoolyard. They walked right through me, refused to move when I walked by them, and generally acted as though I was not there—which, in a way, I was not.

For a while I had a horse named Perhaps, who brought me some solace, although he could never replace Alexis. We cleared out a dusty stall in one of the old barns on the estate for him. Since we lived in such a remote area, I could ride him up and down the road without any danger. I had Perhaps for a year and a half. The second winter, it was extremely cold and I could not ride. By then I was battling not only loneliness, but what would now be called depression and anorexia. My mother quietly gave Perhaps away to a local horse farm. As a teenager going through a tailspin, I had neither the maturity nor the energy to care for a horse.

It was when I stopped eating that my father finally took action. With no notice and against my will, I was admitted to the local hospital. I was terrified. For a week, my blood was drawn and tests were run to check for every conceivable affliction. All the doctors could find was an underactive metabolism, for which thyroid supplements were prescribed. I was also given a psychotropic medication—I believe it was Ritalin. However, it had no beneficial effects; it certainly did not make me less lonely. I told my mother that I did not believe I needed it, and she agreed. The prescription was not renewed. The thyroid supplements, on the other hand, did seem to work. My menses came back, and so did my appetite. This satisfied my dad.

The only thing that ever did me any good in high school was my participation in the movement opposing the Vietnam War. I have read that Aspies have a keen sense of social justice. I would like to say that this was what finally motivated me to stand up for myself. The truth was, I was spurred on by an intense identification with the innocent Vietnamese peasantry, who, through no wrongdoing, saw their huts burned, their villages strafed, and their kinfolk decimated. Wasn’t that similar to what had happened to me? While I was undergoing tests in the hospital, I pored over news magazines to ease the boredom, and the articles I read instilled in me a renewed sense of purpose. Shortly after my release, I began hiking a mile to the bus stop, taking the bus to Poughkeepsie, and holding candles against the wind, marching with signs to demand peace and volunteering for antiwar candidates. I wrote letters to the editor of the school newspaper and spoke up in class. Many of my teachers were likewise opposed to the war and looked upon me with favor. With their help, a political science club was organized, and at last I found classmates with whom I shared an interest. While I never made friends, as Alexis had been, I finally had people to talk to every now and then.

College Was a Disaster

If high school had been tough, college was an utter disaster. At first, I resisted the whole idea, but there did not seem to be a feasible alternative. I had very little guidance in choosing a career path. A large IBM headquarters had been built in a nearby town, and the people who worked there were paid a much higher salary than anyone else around. I never learned what it was the IBM folks did, but it was assumed that all the “bright” kids would try to get such a job, if not at IBM then in a similar firm. In preparation for such a position, one had to go to college. The entire prospect scared the living daylights out of me, but I was completely unaware that there were other options.

If a young Aspie came to me today and asked for advice, I would say, “Above all, choose a work environment in which you can thrive and be productive.” Not everyone is cut out for the corporate life. Would you be happier working on a ranch? In a zoo? Designing sets in a theater? Punching tickets on a train? As for me, it took many years—and many false starts—before I realized that work does not have to entail a windowless cubicle or a forbidding high-rise.

In the end, I selected Catholic University in Washington, DC. I selected it for no legitimate reason other than I thought it would be exciting to live in the nation’s capital.

It was a bad fit from the beginning. The student body was homogenous to the extreme—all white and middle- to upper-middle class, all perfectly attired and perfectly behaved. I found no diversity of thought, either. Somehow, it seemed I had chosen the only university in the l970s without its share of hippies, counter-culturalists, or freethinkers.

I Wanted to Be Social but Was Rebuffed

I wanted very much to be social. I tried very hard to make friends, but I was constantly rebuffed. I tried to establish relationships with young men, to no avail. Unable to find a warm welcome on campus, I spent a lot of my time in the downtown area, running wild in the streets and attempting to latch onto the radical groups who eventually rejected me, as well.

In truth, I was not an attractive person when I was in college. My parents, for all their poor nurturing skills, had at least provided me with some structure. They cooked my meals, did my laundry, saw to it that I went to bed at a reasonable hour, and got me off to school the next day, adequately dressed and groomed. Without their guidance, I did what was right in my own eyes. I bought an oversized khaki jacket from the army supply store and wore it day in and day out. What had begun as innocent idealism had devolved into full-blown anarchism. I was so full of resentment that I wanted to bring the world crashing down with me. I walked around campus muttering about the coming revolution and the “military industrial complex.” My hair was uncombed and uncut. Showers grew more and more infrequent. I plastered my dorm room with controversial posters.

The school administration attributed my weird behavior to drugs, which was a fair assumption. Illegal drugs were rampant on college campuses in those days, and it was known that students who abused drugs acted in strange ways. In truth, I never really took drugs, but the college officials searched my dorm room regularly anyway.

Things came to a head at the end of my third year, when rumors swirled around campus that I had attempted to do someone an injury. Although the rumors were completely false, no one came to my defense. I was subjected to a psychiatric examination. I must have passed the exam, because I was readmitted to the university. It was too late, however, to salvage my college career or my faith in humanity. I spent the next 2 years holed up in an off-campus apartment, gorging myself on my favorite foods and rarely attending classes.

Once I graduated, then I had a real problem—what was I supposed to do next? I was in my early 20s and had absolutely no clue as to how to live an adult life. If I had not been rescued, I do not know what would have become of me.

EMPLOYMENT

A Kind Aunt Helped Me Get My Life Together

My dad’s older sister, Aunt Rose, graciously took me in. She cleaned me up, gave me a bit of a polish, and provided me with some minimal social skills. I returned to the village in which I had lived as a child, and she taught me to bake bread and drive a car. It was far from easy. When I first went to live with her, I had the social graces of one of those jungle boys in the old movies, “Raised by Wolves.” I may as well have been.

Up until this time, I had never worked a day in my life. I hadn’t done any babysitting as a teenager, presumably because I had fallen to pieces and my parents wanted to keep me at home. In high school I did do some volunteer work for antiwar political candidates, but by the time I went to college, I really was in no condition to work.

Aunt Rose helped me look for work. She called up her friends and neighbors and lined up job interviews. She dragged me to career counselors. She found me temporary positions as a lunchroom monitor for the school district, an election registrar, a dog walker, and an office clerk. However, nothing really panned out long-term, so when my parents offered me the opportunity to go back to school, I jumped at it. Reading books and taking tests had never been a problem for me. I earned my master of arts degree, and then I went to law school. Aunt Rose inquired whether I would not be more comfortable with some “quirky, offbeat job” (her words). She was unaware that I was an Aspie, of course, but she was a keen judge of character. Unfortunately, it would be another few years before I listened to her.

Getting and Losing Jobs

I was 30 years old when I got my first “real” job, working for a lawyer in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The year I spent working in Atlantic City was the happiest of my life since junior high. I had gotten the job entirely on my own merits—no one had called up a friend of a friend. No agency sent me. I had not even responded to an ad. I had just knocked on the door of an attorney who happened to have an important brief due the next day, which he had not even started to compose. I was so proud to be employed. I felt authentic, legitimate, and grown-up. People no longer walked through me. They talked to me with respect. Atlantic City was a good fit for me, too; it almost felt like home. In those days, the city was transitioning from a quaint, rundown, seaside resort to the bustling “Las Vegas of the East” that it is today. There was enough of the quirky old town left to make me feel that I belonged, while I could enjoy the adventure and excitement of venturing into the sparkling new casinos that sprung up at an amazing rate. For the first time, I had money of my own; I no longer had to beg my parents for every dollar. My boss’s secretary and I developed a friendly working relationship. I located an apartment with a landlady who was sympathetic and kind. I made up my mind to stay and practice law in South Jersey for the rest of my life. That summer, I took the New Jersey bar exam. When I passed, my boss threw me a little party. My commitment to my new career was so strong that I put down 2 months’ salary on a secondhand Chevette, which I could drive to the courthouse on the mainland.

I Never Saw the Social Warning Signs

Like many Aspies, I never saw the warning signs, which, in retrospect, I am certain were there. Perhaps my boss was growing irritated with my quirky behavior. Perhaps I was tardy once too often. Perhaps I dressed too casually in his eyes. Maybe it was not all my fault. My boss was a lone wolf himself and simply may have had no desire for a permanent associate that he had to pay week in, week out, no matter what the workload. One Friday afternoon, my boss handed me my paycheck and announced, “This isn’t working out.” I was stunned and completely blindsided.

A Kick in the Pants

Losing that first job sent me into another tailspin. I hopped in my Chevette and headed west, looking for another place where I might feel that I belonged. I spent the next year on the road, sometimes picking up work along the way. For 6 months, I worked for a small-town lawyer in Colorado. He asked me to stay, but the twin demons of loneliness and homesickness landed me back on Aunt Rose’s front porch, begging her to take me in again. She agreed, but on one condition. Aunt Rose gave me what she called “a kick in the pants.” This time, there would be no “moping around.” I would have to work. Even though I experienced depression and anxiety, when I was working steadily, the depression receded. I am glad I found work and actively developed the skills that steady employment requires.

My first job upon returning to Aunt Rose was my worst. I was hired by the collections department of a magazine in lower Westchester County. The work was borderline scummy—extracting money from struggling start-up businesses who could not afford to pay their advertising bill. The owner of the magazine treated everyone very unkindly. She ranted and raved and made demands that could not be satisfied. She spread stress around like butter on toast. No one lasted very long in that office; the turnover was phenomenal. She hounded people until they quit. I gritted my teeth and hung on for a year and a half, until I too could take it no more.

Two weeks after I left the magazine, I ran into a local attorney who said he might have some work for me. He did not mean putting me on the payroll or giving me a regular job. He wanted me to help him on a per diem basis, whenever his workload became overwhelming. This finally opened my eyes. I did not have to squeeze myself into that “windowless cubicle,” corporate-type job after all. I had marketable skills. I could freelance. In every small town, there is at least one solo practitioner who has neither the money nor the inclination to hire another full-time employee but who will invariably have special projects from time to time for which assistance is required: filing papers, serving process, answering the court calendar, conducting legal research (my specialty), and drafting briefs. I even helped one attorney supplement a legal treatise. I had a business card printed up, and, before I knew it, my phone was ringing.

Now, this was not “career success” in any conventional sense of the word. My income was erratic and modest at best. I did not have benefits. However, at long last, I was being productive, exercising my skills, and performing tasks at which I excelled, while avoiding undue stress and office politics. I had found my own comfort level, midway between the prestigious, high-salaried law-firm job that my father desired for me and the “no-good lazy bum” that I had been on the road to becoming.

A Strong Attachment to Familiar Places

I did not yet know what was “wrong” with me, but over the years, I came to recognize and accept certain autistic traits in myself, chief among which was a strong attachment to familiar people, places, and things. I felt safe and secure living back in my hometown, even though my childhood friends had long since grown up and moved away. Walking down streets on which I had biked as a child and shopping at stores where I had shopped for years kept my inner chaos at bay. When people asked me why I did not go back to the city to look for a “real” job, I replied that I was needed here to care for an elderly aunt. In truth, it was the other way around. My elderly aunt was taking care of me.

I supplemented my income with colorful, quirky part-time jobs. I was a night clerk in a motel. I handed out coupons in the supermarket. I worked on village elections. My all-time favorite job, prior to my present one at Kykuit, was as a photographer’s assistant and order taker for a studio that photographed high-school proms. For 20 years, until the company folded, I worked at the proms from April to June. For those 20 years, I lived for the spring. This job provided me with the opportunity to dress up and visit places I otherwise would never have seen—country clubs, fancy hotels, and catering houses—while listening to music and watching the young folks in their gowns and tuxedos. Best of all, it had social benefits. I met people, and I fraternized with other crew members.

Work Filled a Void in My Heart

Work filled the void in my heart where a social life should have been. After moving away from Alexis, I never made any close friends, with one exception. One of the small advertisers that I had to visit for the magazine collections department was a young attorney who had recently opened her own law office. We got to talking, and we ended up working together for more than 12 years. She acted as a public defender—the court would assign her as appellate counsel for persons convicted of crimes, and I did the legal research and drafted the briefs.

Attempting to free someone from jail seemed a worthwhile goal. I liked the moral purpose of it. The attorney and I went to visit our clients in prison, and we had “power lunches” at a diner, where we would spread the case record out on the table and hash it out over a burger. We also got together socially on occasion, visiting each other’s homes or going shopping or to the beach. Eventually, she moved on with her career, and as a result, I found my present job at Kykuit.

RELATIONSHIPS

My Relationships with Men

My relationships with the opposite sex have been strange to say the least. I rarely dated in the conventional sense. Instead, in my younger days, I often engaged in an activity that today would be called “stalking.” While I truly intended no harm, I experienced unbearable loneliness, and if a handsome young man appeared on the periphery of my solitary life, my better judgment deserted me. I was drawn toward men who seemed to possess all the attributes I would have wished for myself—charm and popularity or a talent for singing, acting, or athletic ability. There were men who asked me out and tried to form relationships with me, but they held no attraction for me at all. I would rather chase what I could not capture. I only wanted what was unattainable and scorned every man that was actually available to me.

Learning about Asperger’s

It has always been a mystery to me why I engaged in “stalking” types of behavior. I have analyzed it as I would a legal problem and still come up empty-handed. It even puzzled my therapist. She suggested that I write to Dr Tony Attwood, a world-famous expert in Asperger’s syndrome. I did, and he actually wrote back. Dr Attwood replied that many Aspies engage in stalking-type activity and likened it to a special interest. Another person becomes the object of fascination, rather than an academic subject or a set of facts.

About 12 years ago, one of the attorneys I worked for sent me to the library to research Asperger’s syndrome. He represented a local couple whose 18-year-old son had received a diagnosis of Asperger’s. The attorney wanted to know if an adult Aspie would be considered legally competent to handle his own affairs. I asked my boss what Asperger’s was. He said, “It’s a little bit autistic.” I had not read much before I realized that all the symptoms described in the literature applied to me. At that time, however, it was just a label. It was good to know that there were people like myself out there, but the information seemed of no practical value. It was just another obscure fact I had collected. After all, I was already over 40, and I thought any opportunity for a better life was far behind me.

Finding My Tour Guide Job

Then, in the winter of 2002, I came across an ad for part-time tour guides at Kykuit, the Rockefeller Estate. I had grown up when Nelson Rockefeller was the governor of New York, and, history and politics being special interests of mine, I knew something about the Rockefeller family. However, Nelson had died some years before, and since then I had not given him a passing thought. I did need a new part-time job, though. My attorney-friend in Connecticut was closing her practice, and that source of income had to be replaced. Kykuit sounded like fun—just the kind of quirky, offbeat work that Aunt Rose had wisely suggested I might be most suited for (like my job working at the proms, which I loved). I sent in my application, and it was the best thing that ever happened to me in my adult life.

To this day, I wonder how I passed the screening process. I persuaded one of my attorney-bosses to write me a recommendation, and I was hired. Everyone I work with at Kykuit is ten times more poised, graceful, self-assured, and sophisticated than I could ever be. That was the glamour that drew me to them. I wanted to be one of them.

I Love My Tour Guide Job and Learned How to Keep It

I loved the job from the start. The subject matter was right up my alley. Soon I could spout off the names and dates of Chinese dynasties and modern art movements as though it was second nature. The site itself was beautiful, wondrous, and a natural haven for a troubled mind. That is why the first John D. Rockefeller built it—as a refuge from a world that had provided him with amazing financial success but hated him for it. Best of all, the other guides did not automatically shun me or call me ‘weird.’ Many of them were older women, and when my mother died, they comforted me and got me through it. The job provided me with the structure I needed in my life. When you are writing a freelance legal brief, you can get out of bed or not; there is no one standing over you. However, when you are scheduled to conduct a tour at 10 o’clock in the morning, you’d better be there, or else. I was so desperate to keep this job that I forced myself to look visitors in the eye, even when I didn’t want to. I looked at my watch and hurried my groups along so I wouldn’t run late; I concentrated on speaking with inflection and projecting my voice. Talking for 2 hours was not the part that was difficult; like many Aspies, I can talk a blue streak on a subject in which I am interested. The trick was talking in a way that made people want to listen. All through the winter between my first and second seasons, I practiced before the mirror, like a trial lawyer preparing his closing argument. I tried out my new techniques with Aunt Rose. I knew I had finally found a place where I felt I belonged.

By dint of sheer self-will, I developed enough skills to hang on to my job. I became an adequate guide, and then, over the years, I became a very good guide. The job became my anchor through all the rough patches to come, such as the death of my father and Aunt Rose. In the case of Aunt Rose, not only had I lost my caregiver, but I had lost the last person in the world who really cared about me.

Losing My Family Was Very Traumatic

I imagine that losing one’s family is traumatic for anyone, but to an autistic person it can seem like the worst thing that could happen. Many of us lack the ability to form strong friendships or relationships, and when we lose our family of origin, there is no one to fill the void. After Aunt Rose died, I had to vacate her home, and this increased my stress levels. Depression and anxiety overwhelmed me.

However, the Kykuit season was about to start, and I liked guiding so much that I decided to seek therapy and find out, once and for all, what was “wrong” with me. In this manner, I came to receive a diagnosis of Asperger’s at the age of 54. I delved into learning about my diagnosis. I read books and scoured the Internet for information on the autism spectrum. I met other adult Aspies, both online and in person. I was pleased to find that, although my autism would not go away, my symptoms could be alleviated with small doses of an antidepressant (buproprion) and an antianxiety medication (klonopin).

Diagnosis Gave Me a New Perspective

A wise Frenchwoman once said that to understand all is to forgive all. Once I began to understand myself, I looked at the pattern of my past through a new perspective and began to forgive myself for all the repeated mess-ups in my life. I felt that I was finally able to move on.

At Kykuit, I had rediscovered the Real Me—the brave, spunky child that I was before I sank down into despair. My job as a tour guide has at last offered me an opportunity to shine and to develop skills I always wanted to possess. My self-Confidence has grown, and I have actually been able to make friends.

I have added my own unique spin to the tour, which visitors seem to love. While my colleagues focus on the more dynamic characters of the Rockefeller family—John D. Rockefeller, Sr, or Nelson Rockefeller—I often talk about the generation in between. John D. Rockefeller, Jr, and I have a lot of traits in common. Like me, he had a hard time fitting in. He was fascinated by history and classical art. He felt so out of place in the 20th century that he built Colonial Wil-liamsburg and spent a portion of each year at his home there. Just as the image of the IBM cubicle was impressed upon me in my youth as the archetypal job, “Junior” was always expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and take over the Standard Oil Company. Like me, he had a lot of false starts, disappointments, and inner struggles before he realized he was simply not cut out to be a corporate executive. He knew he had to chart his own course in life.

Reconnection with My Childhood Friend

Last summer, a Christian tour group visited Kykuit, and I was their guide. One of the ladies had an identification tag with the name of the small town in North Carolina to which Alexis had moved 30 years before—the last time I had heard from her. As a lark, I asked the lady whether she knew Alexis. To my stunned delight, another visitor suddenly exclaimed, “Alexis? I work with her!” As it turned out, the visitor was a nurse at a hospital where Alexis is the chaplain. I gave her my e-mail address, and now I have reconnected with my childhood best friend. This is the kind of intangible treasure I have found through my work at Kykuit.

I have never become exactly like the other guides here, but in my eyes I’ve managed to become something even more meaningful. I’ve finally become myself.