Читать книгу Sisters of the Revolutionaries - Teresa O’Donnell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The Childhood of Margaret

and Mary Brigid Pearse

The half-real, half-imagined adventures of a child are fully rounded, perfect, beautiful, often bizarre and humorous, but never ludicrous.1

Patrick Pearse

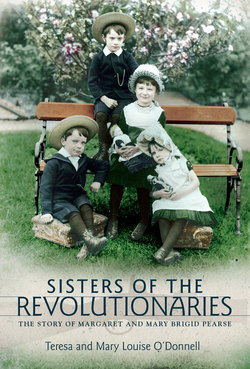

Margaret and Mary Brigid Pearse were the eldest and youngest of four children born to James (1839–1900) and Margaret Pearse (1857–1932). The children were born above their father’s business premises at 27 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin (now Pearse Street); Margaret Mary was born on 4 August 1878, Patrick Henry on 19 November 1879, William James on 15 November 1881 and Mary Bridget (later changed to Brigid) on 26 April 1884. All were baptised at St Andrew’s Church, Westland Row, Dublin. Personal accounts of Margaret, Mary Brigid and Patrick recall memories of a happy childhood, a close-knit family and a religious upbringing. Margaret wrote, ‘[o]ur schooldays and youth were very happy with our loving mother and most devoted father. Our pleasures were simple, [and] cultural’.2

Their father, James Pearse, was born on 8 December 1839 in Bloomsbury, London, to Mary Ann Thomson, a Unitarian, and James, a free thinker. James (junior) had two brothers, William and Henry, and, according to the 1851 Census, the Pearse family were then living at Ellis Street, Birmingham. Due to straitened financial circumstances, the three boys worked from an early age and, consequently, received little education. James worked at various jobs, eventually becoming a sculptor’s apprentice. He attended drawing classes in the evening and in his leisure time was an avid reader. After serving his apprenticeship, James moved to Dublin c.1859–60 to take up the position of foreman for the English architectural sculptor, Charles Harrison, who had premises in Great Brunswick Street. In the mid-nineteenth century, there was a boom in the building of churches in Ireland and a number of English craftsmen worked from premises in Great Brunswick Street, Westland Row and Townsend Street. James, however, retained his links with Birmingham and was recorded in the 1861 Census as being a visitor to the city. He also travelled back to Birmingham to court and eventually marry Emily Susannah Fox on 28 April 1863 at St Thomas’ Church, Birmingham.

James and Emily settled in Dublin shortly after their marriage and, in 1864, he commenced a three-year contract with the firm, Earley and Powell, 1 Upper Camden Street, Dublin, who were specialists in stucco work, stained-glass manufacturing, carving and plastering. James and Emily’s first child, Mary Emily (known as Emily) was born in 1864 and a son, James Vincent, arrived two years later in 1866. The family converted to Catholicism sometime after James Vincent’s birth as two daughters, Agnes Maud (b.1869) and Amy Kathleen (b.1871), were both baptised Catholic. The Pearse family was received into the church in Mount Argus, Dublin, under the guidance of Fr Pius Devine, a Passionist priest and rector who was impressed with the manner in which James and his family undertook the process.3 It is unclear, however, if the family’s conversion was in earnest or merely to increase James’s prospect of gaining increased commissions from the Catholic Church. Whatever his motivation, James benefitted from the patronage of the Catholic Church from the early 1870s onwards. He formed a partnership with Patrick J. O’Neill c.1873, based at 182 Great Brunswick Street, which lasted until 1875. Although James enjoyed professional success in this period, his personal life was tinged with tragedy. Both Agnes Maud and Amy Kathleen died in infancy and Emily died from a spinal infection at the age of thirty on 26 July 1876.4 James and Emily’s marriage was a not a happy one and he blamed the death of at least one of his daughters on his wife’s neglect.

After Emily’s death, James, Mary Emily and James Vincent resided at the home of their friend, John Thomas McGloughlin, 5 Parnell Place, Harold’s Cross until James married his second wife, Margaret Brady. She was born on 12 February 1857 to Bridget Savage, a celebrated step dancer from Oldcastle, Co. Dublin, and Patrick Brady, a coal factor from Dublin. The Brady family lived in North Clarence Street, Dublin but also had a property at 7 Aldborough Avenue. Margaret and her sister, Catherine (b.1852), received their education at the Daughters of Charity of St Vincent de Paul School, North William Street which was established by the Religious Sisters of Charity in 1825 and later transferred to the Daughters of Charity in 1857. While working as an assistant at a newsagent and post office on Great Brunswick Street, she met James Pearse, a customer who purchased a newspaper every morning on his way to his rented premises at 27 Great Brunswick Street. After the death of his first wife, James had a clear vision for his future happiness. Letters written during his courtship with Margaret emphasised his belief that the creation and sustainment of a loving and secure home environment was the key to achieving true happiness:

I think it must be a great blessing and consolation to be permitted to pass through this world of change with one who will be all to you at all times, one whom you can turn to when the world frowns. A home in which you can find peace and rest. I believe I could make great efforts to render such a home happy.5

James cited Margaret’s homeliness as one of her most appealing characteristics. He described her as ‘a grand looking woman with dark hair and eyes, no nonsense about her, plump and ... homely yet bright and full of life’.6 It is unclear exactly when their courtship began, but by the end of 1876, a mere five months after the death of James’s wife, they had already met for a number of dates at Bachelor’s Walk and the corner of Westmoreland Street and Carlisle Bridge (now O’Connell Bridge). The courtship was not always smooth as is evinced from some of their correspondence housed at the National Library of Ireland. Due to illness, James and Margaret were unable to meet from Christmas 1876 until some time after St Patrick’s Day (17 March) 1877. James declared that the more care he took of himself, the worse his condition became.7 Nevertheless, Margaret’s patience was beginning to wane and she expressed doubts about the viability of their relationship and dissatisfaction that she had not met his children. But James was determined to continue their courtship, declaring that Margaret’s affection had filled ‘a great void in [his] existence.’8

After a brief engagement, James and Margaret planned their nuptials for 24 October 1877 at the Church of St Agatha, North William Street, Dublin; she had been baptised there on 16 February 1857. Despite the fact that it was commonplace for widowers with children to remarry and that Margaret’s marriage would have been regarded as a good match in terms of social class, Margaret’s parents had some reservations about the impending nuptials, in particular, the challenge for Margaret of raising two step-children. To the annoyance of the young couple, they suggested the wedding be delayed by a few weeks. James insisted that Margaret’s family were aware of his good character but he accepted that Margaret’s parents only had their daughter’s interests at heart. He implored Margaret to be patient and to inform her parents ‘to save their scolding for’ him.9 The wedding was not postponed and both Patrick and Bridget Brady attended the nuptials. Margaret’s sister, Catherine, of 160 Great Brunswick Street, and James’s friend, John McGloughlin, acted as their witnesses. By all accounts, the marriage of James and Margaret was a happy one; they set up home (and business) along with Mary Emily and James Vincent in a rented property at 27 Great Brunswick Street, a large building which was sublet to other families.

Eighteen seventy-eight proved to be a productive year for James. He embarked on a ten-year partnership with his foreman, Edmund Sharp, and in August of that year, Margaret gave birth to their first child, Margaret Mary, known as ‘wow-wow’ and ‘Maggie’ to her family. Margaret was a precocious, bossy child. She adored her father ‘Papa’ and was very proud of his achievements. He, in turn, indulged her every whim. Fifteen months after her birth, Patrick Henry was born. Patrick became seriously ill at the age of six months and the family doctor advised that there was a poor prospect of survival; the infant, however, survived. Their half-sister Emily later wrote about Patrick’s ‘sweet uncomplaining patience’ during his illness and she noted that this was part of the young Patrick’s gentle nature and natural reserve.10

Patrick’s earliest recollection of family life was of playing with his sister in the dimly-lit living-room in the basement of their home in Great Brunswick Street and the distinctive sounds of that space:

the carolling of the black fire-fairy, the ticking of a clock, and the rhythmic tap-tapping which came all day from the workshop. In this tap-tapping there were two distinct notes: one sharp and metallic, which I knew afterwards to be the sound of a chisel against hard marble; the other soft and dull, subsequently to be recognised as the sound of a chisel against Caen stone.11

Margaret was delighted to have a younger sibling with whom she could play, but perhaps, more importantly, whom she could ‘enlighten’. As the elder sibling, Margaret’s opinion invariably prevailed. Patrick recalled, ‘[s]he insisted that her wisdom and experience were riper than mine, and, by dint of hearing this again and again repeated, I came to believe it and to entertain for her a serious respect.’12 On one occasion, Margaret encouraged Patrick to cut the tail off a toy horse his father had brought him from London; because the mane and tail of the ‘London horse’ were made of real horse’s hair, Margaret convinced him that it would grow back. When it did not, Patrick soon realised that Margaret was not as wise or knowledgeable as she unfailingly led him to believe.

Margaret and Patrick played happily together as young children but because she was ‘both bigger and of a more dominating character’,13 she dictated the content and nature of their playtime, which frequently irked Patrick. She had a particular penchant for re-enacting battles that occasionally resulted in fatalities. Patrick believed that Margaret should take responsibility for burying her own dead, but to his great annoyance, Dobbin, a treasured wooden horse carved by his father, was often commandeered to carry the dead on a solemn journey for burial at Glasnevin Cemetery. These childhood games were simple but fondly remembered. Margaret and Patrick were most content sitting with their parents in the drawing room in front of the fire watching the fire-fairy or playing with their pets, Minnie, the lazy cat who invariably positioned himself at the centre of the hearth, and Gyp, their accident-prone hyperactive dog.

Margaret and Patrick had many adventures in their drawing room in Great Brunswick Street, traversing its floor ‘in sleighs, in Roman chariots, in howdahs on the backs of elephants’ and bravely travelling into remote corners of the room ‘where wild beasts prowled’.14 The children believed that their toys came to life at night time when silence descended on the household. They imagined that their dolls competed in races on the ‘London Horse’, that their toy cows grazed under the furniture and that Patrick’s white goat climbed the treacherous vertical cliff otherwise known as the Pearse’s couch. One night, while Margaret slept, Patrick crept downstairs to observe their toys’ nocturnal adventures, alas with no success. Fear of the dark prevented Patrick from spying on the toys again.

Margaret and Patrick were raised with their ‘devoted half-sister’15 Emily and half-brother James Vincent. Emily was often charged with caring for her siblings and she taught them to read and write. She was patient and encouraging to her eager students and fostered in them a love of reading, which had been nurtured in her by her father. James read widely and his library included books from a variety of genres such as biblical studies, Irish and European history, literary classics and dictionaries. His collection also included a copy of the Koran and biographies of William Cobbett and John Wilkes, both radical journalists and supporters of Catholic emancipation. Although James may have read to his children, it was Emily’s magical stories filled with heroic figures and mythical monsters that stimulated their imaginations. In the years that followed, the Pearse children would re-enact many of these early childhood fantasies in the theatrical setting of their parlour.

Margaret and Patrick were constant companions in their formative years, but the arrival of their brother William James (Willie) in 1881 ended forever the close bond they had shared in early childhood. Their mother became seriously ill following Willie’s birth and the newborn was sent to be cared for by his grand-uncle Christy and his wife Anne (née Keogh) on their farm in north County Dublin. Willie was reunited with his mother after she had recuperated, but the experience traumatised the entire Pearse family. Patrick later recalled:

It was a long time before my mother came down to us again. When she did come, looking very pale, one of the first things she did (after pressing my sister and myself to her heart) was to go over and kiss Dobbin; and in gratitude for that gracious kiss I told her that I would consider the little brother (who returned to us the same day) entitled equally with me to bestride that noble steed, as soon as his little legs should have the necessary length and strength to grip on. For the present they were obviously too fat for any such equestrian exercise.16

The final addition to the Pearse family arrived in April 1884; Mary Bridget (later changed to Mary Brigid) was named after her two grandmothers and her arrival generated much excitement in the Pearse household. When the nurse announced that the doctor had brought them a little sister, the children enquired from her how much their father had paid for the little girl; she replied, £100. On the day of her birth, their mother placed the infant in the arms of her siblings.17

Less than three months after Mary Brigid’s birth, on 5 July 1884, Emily married Alfred Ignatius McGloughlin, an architect and son of her father’s friend John, at St Andrew’s Church, Westland Row. Margaret was a junior bridesmaid at the wedding and Patrick carried his half-sister’s train from the carriage into the church. Emily described Patrick as ‘a comely little page, royally dressed in ruby velvet and heavy lace, a truly princely little figure; reserved, shy, and silent, with a wonderfully calm self-possession which sat strangely on his small figure’.18

Margaret, Patrick and Willie enjoyed Emily’s wedding, in particular, the apple pie served at the wedding breakfast. It was not until the arrival of their beloved Auntie Margaret at the kids’ table, however, that they were completely at ease. Emily’s gift to Margaret and Patrick for carrying out their roles so competently at the wedding was a scrapbook into which she pasted thousands of pictures; images of dragons, fairies and giants, as well as red-coated huntsmen, circus horses, harlequins and clowns. Patrick and Margaret spent many hours savouring ‘a book that was full of echoes from a world of romantic and far adventure’, which was so large that it took two children to lift.19 The departure of Emily from the Pearse home left a void in the life of the children. The family, however, maintained close ties with Emily and Alfred’s children, Emily Mary (b.1885), Margaret Mary (b.1886) and Alfred Vincent (b.1888). Indeed, the Pearses were an important support for Emily and her children when Alfred went to New York seeking work and never returned to his family. Left alone, Emily struggled to raise her children and they were placed in an orphanage.20

With his second family, James Pearse enjoyed the idyllic home life that had been absent from his first marriage. Margaret was a loving wife and mother with a kind and gentle nature. James was a quiet, mild-mannered man whose deep reserve disappeared when he tenderly embraced each of his children before putting them to bed. James was devoted to his family and took a keen interest in his children’s diet and general well-being. In some of the letters written while he was away on business in England, however, he comes across as bossy and occasionally neurotic. He often wrote to his wife instructing her to ensure that she and the children ate nourishing food, were properly attired so they would not catch cold and were cautious around the fire. In one letter, James even reminded his wife to put into a cool place, the succulent beef and ham he had purchased before his departure for England.21 He encouraged Margaret to bring the children to the seaside on sunny days but cautioned that she should ‘be extremely careful with the kiddies’ in case they might catch cold.22 All letters to his wife ended affectionately with kisses for the children: ‘[k]iss the children dearest for me. Also let them kiss you on my account’23 and ‘[t]ell Wow wow and Pat to give you some bigger [kisses] for Papa.’24

James’s personal happiness coincided with a period of professional success and a foray into the world of political commentary. He kept abreast of political developments in England and was a supporter of the radical Liberal MP, Charles Bradlaugh. James was particularly interested in the agitation for Home Rule and, in 1886, wrote ‘A Reply to Professor Maguire’s pamphlet “England’s duty to Ireland” as it appears to an Englishman’ in which he lambasted Maguire’s criticism of the Home Rule movement and his offensive anti-nationalist commentary. The publication of this pamphlet, funded entirely by himself, was the culmination of many years of self-education. Recognising the importance of education, James enrolled Margaret and Patrick, aged eight and seven, at a private school run by Mrs Murphy and her daughter at 28 Wentworth Place, Dublin (now Hogan Place), in 1886. They studied a variety of subjects there and were also enrolled in dance classes with Madam Lawton. By all accounts, Patrick did not enjoy the experience and during his time at school labelled Mrs Murphy ‘the presiding dragon’.25

Within a few months of starting school, the family moved to a new house. The expansion of James’s business and family necessitated a move to a larger house and the property on Newbridge Avenue, Sandymount, with its large garden and apple trees, appealed to the young Pearse children, who spent many happy hours there playing with James Vincent and their cousins. However, within a few months of moving to Sandymount, Patrick contracted scarlet fever, an infectious disease that also affected Willie. Their mother’s paternal aunt, Margaret, moved in with the family to tend to the sick boys while the girls moved back to Great Brunswick Street, which had not been sold but was rented out to other families, thus providing an additional source of income for the Pearse family.

Auntie Margaret, as she was called by the children, was a strong influence on the young Pearse siblings and the stories she told shaped their imaginations. Although James’s father and his older and younger brothers, William and Henry, visited the family in Dublin on a few occasions, the Pearse children had little contact with their father’s extended family. In contrast, the children were frequent visitors to their mother’s relations and were very familiar with the history of the Brady family. Their colourful ancestors were brought to life by their beloved Auntie Margaret. She regaled the young Pearse children with stories about their great-great-grandfather, Walter Brady, and his family’s involvement in the 1798 Rebellion. Walter was a Cavan man who settled in Nobber, County Meath and fought in the Rebellion; his brother was hanged by the Yeomanry and another brother was buried at the Croppies’ Grave at Tara. The family of their great-grandfather, also Walter Brady, were native Irish speakers and steeped in Gaelic culture. Walter had an impressive repertoire of Irish- and English-language songs. He, his wife Margaret (née O’Connor) and eight children, later moved to Dublin to avoid the ravages of famine in north County Meath, but, as a child, his daughter (Auntie Margaret) fondly remembered social gatherings in their home accompanied by music, storytelling and dancing.

The storytelling tradition was perpetuated by Auntie Margaret, who entertained the Pearse children with the legends of Fionn and the Fianna and stories about Robert Emmet, Theobald Wolfe Tone and Napoleon Bonaparte. She sang political ballads about those who died in the 1798 Rebellion and the Fenian Rising of 1867, and the children particularly enjoyed her rendition of ‘The Old Grey Mare’ (see Appendix 1). Louis Le Roux acknowledged the influence of this elderly grand-aunt who had witnessed the birth of major political and cultural movements in the nineteenth century such as Young Ireland, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the Land League. He noted that ‘[s]he had wept with Ireland, hoped with Ireland and prayed with Ireland for three-quarters of a century.’26

Whether she was tending to the Pearse children during illness or just calling to visit, the diminutive figure of Auntie Margaret, her kindly wrinkled face, grey hair tied back in a net and black dress with collar buttoned to the throat, was always welcome.27 At Sandymount or Great Brunswick Street, they recognised her step on the stairs, ran to greet her, and spent hours creating marvellous stories about the sights and sounds of their neighbourhood. They were fascinated by the doctors making their way to the Children’s Hospital, by the sounds of the trams and the mail cars en route to Westland Row, and, in particular, by the man detaching his van from a grey horse and then rewarding the horse’s arduous day’s work with a feedbag.28

The care and love shown by Auntie Margaret to Patrick and Willie during their illness with scarlet fever was later replicated by Patrick towards his youngest sister. The exact nature of Mary Brigid’s illness is unknown, but she suffered ill-health from a young age. She was often confined to bed for extended periods and, consequently, did not receive her education at school. Mary Brigid was often indulged and spoiled as a child. Her social circle consisted of her sister and two brothers, but her closest bond was with Patrick. To say she idolised him would not be an exaggeration. During her periods of convalesence, it was Patrick who temporarily relieved her suffering and boredom by reading about the adventures of fascinating characters in weird and wonderful places. Characters in books, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, The Wallypug of Why and Prince Boohoo and Little Smuts were brought to life by Patrick, who often sat for hours with his sister. Even at a young age, he was a confident speaker and his dramatic interpretation ensured that stories such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a ‘pulsing heart-thrilling reality’.29 Mary Brigid appreciated the enthusiasm with which he approached every narrative; as she later recalled:

I was a pitifully delicate child, always ailing and nearly always confined to bed. One of my strongest and pleasantest recollections is that of my brother reading to me every evening when he came home from school. Oh, how I used to yearn for my brother’s return! How many times would I ask my mother: ‘Are the boys in yet?’ How my childish heart would throb tumultuously when at last Pat’s quick light step was heard on the stairs, and his eager face appeared in the doorway!

And then came the long delightful hours of supreme content and quiet rapture, when I could forget my pain and weariness in listening to that tireless fresh young voice. Very often Pat would not even wait to take his dinner, and then mother used to carry both dinners up to my room, and we would eat the meal cosily together, Pat reading and eating at the same time! We used not to speak much, excepting when my brother would explain a word or passage, for both of us were curiously shy. But there was a close bond of sympathy between us, notwithstanding, and we enjoyed our readings immensely.30

Mary Brigid and Patrick also enjoyed stories such as ‘Doctor Spider’ from the Little Folks series, or other popular children’s stories serialised in The Strand Magazine, the Irish weekly, The Shamrock and the English Catholic magazine, St Peter’s. They always delighted in stories about animals and had a fondness for toy animals, Mary Brigid cherishing into adulthood many of the toys Patrick had given her as a child.31 Mary Brigid spent extended periods on her own, so gifts such as a swan made from celluloid and a family of pigs fashioned from a pen-wiper helped her to pass ‘away many a weary hour of loneliness and pain’.32 Patrick wrote a weekly newspaper for the family that included short articles, jokes, puzzles, and a regular story entitled ‘Pat Murphy’s Pig’. Although the weekly newspaper was handwritten in an ordinary exercise book, Mary Brigid keenly awaited its weekly arrival. In fact, she delighted in any opportunity to spend time with her brother.

One could argue that the remarkable respect for and insight into children’s minds which Patrick displayed in the latter part of his life was formed during the time he spent educating his younger sister and fostering in her a love of learning. The hours that Patrick and Mary Brigid spent together as children definitely had a lasting effect on both siblings. Mary Brigid wrote plays, children’s stories and a novel. Patrick was inspired by Mary Brigid’s childhood convalesence to write several children’s stories that included sick children as characters such as ‘An Gadaí’ and ‘Eoghainín na nÉan’. In ‘Eoghainín na nÉan’, Patrick told the poignant story of a terminally ill young boy called Eoghainín, who longs for the arrival of the swallows. When they finally arrive, he spends hours listening to tales of their adventures in other countries. As the time approaches for them to migrate to warmer climes, Eoghainín tells his mother that he will depart with them; they watch the swallows leave and, as the last pair fly off, Eoghainín rests his head on his mother’s shoulder and dies. As children, Mary Brigid and Patrick loved to watch the arrival of migratory birds and, in later life, the comings and goings of the swallows always reminded Mary Brigid of her brother.

In between periods of convalescence, Mary Brigid participated fully in the family’s escapades. The young Pearses had a particular fondness for all things theatrical and loved to dress up and to disguise themselves as different characters. Clothes were borrowed from their mother’s rag-bag, or sometimes her wardrobe and Patrick was never rebuked by his mother for taking her seal coat or best silk dress to be used as costumes for the performances.33 Patrick was often joined by his cousin Mary Kate Kelly or his nephew Alfred McGloughlin to play pranks on unsuspecting neighbours or passers by. Alfred recounted the story of when he and Patrick dressed as beggars for a day, travelling around Donnybrook. Alfred came away with nothing but Patrick received a donation of several shillings from a generous elderly lady.34 On another occasion, Patrick and Willie dressed in old clothes and sold apples to help poor children in the neighbourhood. Unfortunately, their charitable endeavours were soon stymied when a group of local ‘ragged boys’, who resented the Pearse brothers appropriating their business, beat them up. Mary Brigid described the encounter in detail noting that, although the brothers tried to defend themselves, they were outnumbered and were relieved when a teenage neighbour intervened to rescue them.35

The Pearse siblings, together with their cousins, nieces and nephews, transformed their drawing room into a stage and performed adaptations of Shakespearean plays or short plays written by Patrick. Each of the children embraced their various roles with enthusiasm. In a performance of Macbeth, with Patrick in the title role and Mary Brigid playing Lady Macbeth, Mary Brigid remembered how Patrick did not always approach his roles in a serious, professional manner:

Unfortunately, however, Pat’s risibility always completely overcame him the instant he addressed me by any endearing term, and he used to break into uncontrollable laughter! This made the whole business absolutely farcical. To see the grave Scotsman holding his sides with hilarity, to hear his helpless peals of mirth was too ridiculous. I used to become seriously annoyed. I would work up the scene most dramatically, and then Pat would ruin it.36

Patrick wrote his first play, The Rival Lovers, at the age of nine and cast Mary Brigid, then only five years old, in a lead role. Patrick and Willie assumed the lead male roles and Mary Kate played Mary Brigid’s mother. During the dramatic duel scene, Mary Brigid was caught in the crossfire and dramatically fell to her death as directed by Patrick. In the years that followed, Patrick wrote several plays for his siblings and relations, including The Pride of Finisterre and Brian Boru. The Pride of Finisterre, set in the Spanish countryside, was an ambitious production written in verse form for eight characters. Mary Brigid played the role of Eugénie (the ‘Pride of Finisterre’), Willie played her lover, Bernard, Margaret was cast in the role of a noblewoman called Marie d’Artua, and Patrick played her villainous husband, Count Alexander.

Lesser roles were allocated to their cousin Mary Kate, who played Eugénie’s mother, and her brother, John, who acted as a priest. Patrick also adapted some scenes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin for performance and wrote a play about love and jealousy that Mary Brigid set to music and performed as a mini opera. The young thespians savoured these early performances and the response of their audiences. As Mary Brigid later wrote, ‘I don’t believe that any of the greatest actors on the stage ever felt such exquisite delight when they received the plaudits of a vast audience as we felt when we “took our curtain” amidst wild clapping from our friends! It was simply the perfection of joy!’37

The subject matter of their performances was not limited to great works of literature or Patrick’s compositions. The young theatrical troupe often acted out religious ceremonies that they had attended at their local church in Westland Row. This church played an important role in the religious upbringing of the Pearse children. Each of them was baptised, received their First Confession, First Holy Communion and Confirmation in this church, and Margaret and Patrick later taught classes in catechism there on Sundays. Margaret recalled that, even in his youth, Patrick had a talent for delivering impressive lectures, especially on religious subjects. At the age of nine, he delivered an insightful sermon to his family on the transfiguration of Jesus Christ; Margaret later wondered how a boy of his age had acquired such a grasp and appreciation of Christian doctrine.38 In their re-enactments of religious ceremonies, Patrick regularly played the role of boy-priest, Willie acted as his acolyte, and the others were his devoted congregation. Unfortunately, the solemnity of the occasion was often interrupted by bickering between Margaret and her younger siblings. Mary Brigid claimed that she and Willie disliked Margaret’s domineering manner, and Patrick was often forced to act as peacemaker ‘for his grave reasonableness was very forceful’.39

Despite his apparent piety, it seems Patrick was the most mischievious of the Pearse children and had a tendency to laugh uncontrollably at the most inappropriate moments. When a fire broke out in Margaret’s room, Patrick quickly grabbed her bedclothes and a rug to quench the flames. After his heroic deeds, Patrick was overcome by a fit of giggles. Margaret, however, was not amused to find that her cherished bed linen and furniture had been destroyed by a cackling firefighter. Mary Brigid wondered whether ‘Pat’s loud laughter in the midst of smoke and fire, or Maggie’s woe-begone face as she surveyed her bedraggled apartment afterwards’ was the more ridiculous.40

Patrick’s love of sweet things was also a cause of contention in the Pearse household. When a pane of glass became loose in the landing window of their home, their father affixed some sticky gelatine sweets to prevent the pane from falling out. Later that evening, James noticed that his temporary confectionary glue was slowly disappearing and soon discovered that his eldest son could not resist taking a sweet every time he passed by the window.41 Similarly, whenever their mother left a freshly-baked rich cake with nut topping on the kitchen table, Patrick would invariably consume the nutty topping and leave the remainder of the uneaten cake behind.42

One Christmas, their mother enlisted the help of her children to make a Christmas cake and pudding. To expedite the process, Mary Brigid chopped the suet, Margaret crumbled and grated the bread, Willie beat the eggs, and Patrick stoned the raisins. Unfortunately, Patrick’s love of sweets, nuts, sugar barley and Turkish delight meant that he consumed more fruit than he stoned. Their mother eventually discovered the considerable reduction in the amount of fruit. She did not chastise her eldest son but moved him to another job, slicing the candied peel. Patrick, however, could not resist the temptation of the sweet candied peel and was eventually relieved of his duties. Following his dismissal, he stretched out on the sofa in the front room and started singing, but he was quickly ordered out of the room by his father who could not bear the racket.

Mary Brigid later filled the pages of her book, The Home-Life of Pádraig Pearse (1934), with similar stories about their childhood antics and, invariably, cast Patrick as the central protagonist, ‘Pat was the leading incentive and presiding spirit of our small company.’43 She related an incident when the Pearses visited their half-sister Emily’s house. The children were happily playing tennis and other games in a field behind the house until they were ordered out by the landlord. Their niece Emily explained to the landlord that he had agreed to let them play in the field and Patrick cheekily retorted, ‘then we will play!’ and so they did.44

As the Pearse children grew older, Patrick and Margaret focused increasingly on their education and achieving excellence in their studies, thus allowing less time to partake in the fun they enjoyed as young children. Memories of their idyllic childhood remained with them throughout their lives. In adult life, Patrick wrote in his autobiography of his desire to return to the serenity of his childhood and ‘to be at home always, with the same beloved faces, the same familiar shapes and sounds’.45 They squabbled, as all siblings do, but James and Margaret ensured that their children grew up in a stable, close-knit and loving family; a happy home where the children’s creative talents flourished.