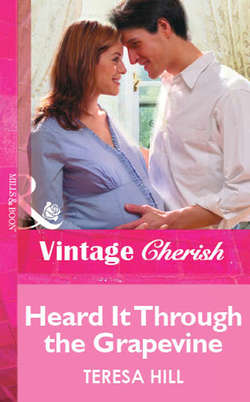

Читать книгу Heard It Through the Grapevine - Teresa Hill, Teresa Hill - Страница 9

Chapter One

ОглавлениеThe stick turned blue.

Cathie Baldwin sank down to the floor of her tiny bathroom. Taking stock of her situation as objectively as possible, she decided she’d never been this afraid, this upset or this ashamed of herself.

She was twenty-three, certainly old enough to know better, and they’d been careful, darn it. So careful.

Of course, as mothers had no doubt been telling their daughters for decades, the only truly safe sex was no sex at all. Which was what she’d had for years. No Sex. She’d waited so long, and now that she’d finally found someone she’d thought was special enough to share her bed…now this.

She looked at the test stick again, just to be sure. If anything, it looked bluer than before.

Fine. Tears welled up in her eyes, and she let them fall.

No one had ever cried forever, had they?

She feared she might set a record in the event. Olympic Gold, Longest Crying Jag in History, Laura Catherine Baldwin, the preacher’s daughter. The good girl. Pregnant college dropout who horrified her father’s entire congregation, shamed her parents, infuriated her four overgrown, overprotective brothers, shocked a dozen aunts, uncles and cousins too numerous to count and generally messed up her life.

And her baby’s.

Oh, God, she was going to have a baby.

Cathie thought she was about as miserable as she could be.

Then the lights went out. Everything in the apartment whined down and stopped. The heat, the refrigerator, the computer. Everything.

She whimpered. Honestly, she was the most pitiful thing. On the way to the kitchen, she cracked her toe on the corner of the coffee table, swore softly as she hopped the rest of the way, her toe throbbing.

In the kitchen, she found the big pillar candle on the counter by the coffeepot. But the matches proved stubbornly elusive. She was feeling along the top of the refrigerator when, just as she thought she found them, her hand hit something else.

It rumbled and rolled on top of the fridge, and the next thing she knew, came flying down and hit her on the forehead.

“Ouch.” She put her hand on her poor head for a moment, then reached up and, finally finding the matches, struck one and lit the candle.

Her first stop after that was the little mirror hanging in the hallway, to check the damage. She had a red splotch on her right temple to match her tear-reddened eyes.

She was headed back into the kitchen to see what had hit her when hot wax from the candle dripped onto her hand.

“Ouch!” For a second, she thought she’d caught her pajama top on fire, that she was cursed for sure. Then the lights decided to come back on.

She groaned, blew out the candle, wiped the dot of hot wax off her hand, and then looked down at the mess she’d made of her own floor.

That’s when she saw the little wooden box in the corner by the trash can.

Cathie frowned at it.

Granted, it had been a really lousy day and maybe she was closer to hysterics than she realized.

Because it seemed a lot like God had just hit her on the head.

Warily, she crept over to the little wooden box as if it might have sprouted wings and flown into her forehead, all on its own. But she’d knocked it off the refrigerator.

That was all.

No big mystery there. No odd powers at work.

She felt silly for still having the thing.

It was her God Box. One of the quaint traditions of her father’s church. A turn-it-over-to-God thing. All the kids got one. For problems they didn’t think they could deal with on their own. Cathie had taken an introductory psych class, so she understood the concept. Letting go of things we simply can’t control or change.

They had a saying in her family: Take it to the Box. She’d done that with so many problems over the years, some of which had been solved and some she was still hoping to see resolved. They were still in the Box, scribbled on little slips of paper.

At least, they had been inside, until she’d knocked the Box off the refrigerator.

Feeling foolish, she got down on her hands and knees, scrambling to find those little papers and stuffing them back inside, as if any of those childhood secrets and wishes mattered now.

Her life had been so much simpler then.

Cathie sat on the floor, glancing warily at the Box, feeling too guilty and too ashamed of herself to say a prayer.

But it wasn’t so hard to say, Help me, please.

Or to write it down.

It felt silly, but she’d been crying forever, no closer to an answer than she had been when the blasted stick had turned blue. She could use all the help she could get.

Scribbling frantically through fresh tears, she managed to get down one frantic plea, then folded the paper up into tinier and tinier pieces, like she had when she was little. She tucked the paper inside and was just starting to think, Okay, what do I do now?

Honestly, it hadn’t been a minute.

When her doorbell rang, she was as startled as she’d been when the Box hit her on the head.

Not a single interior light was visible through the windows of the shabby, old house perched on the edge of the North Carolina college campus.

The house’s paint was flaking, the yard needed mowing, and the police should probably be called to deal with the two men half a block away, guzzling beer, shoving each other and swearing. A cat was on the prowl for its dinner, garbage was piling up on the curb and there didn’t seem to be a functioning streetlight on the whole block.

Matthew Monroe climbed out of his very expensive, steel-gray Mercedes and frowned. What the hell, he thought, activating the car’s security system. No reason to make it easy. Things had been much simpler in his car-thieving days.

Pocketing the car keys, he frowned as he headed for the old house, the last place in the world he wanted to be tonight or any other night.

Because she lived here.

But Mary Baldwin was the closest thing Matt had ever had to a mother, and Mary was worried about her daughter. Which meant someone had to go see if Mary’s little girl was all right. Matt was the closest thing to family Cathie had in town, so he was elected.

He climbed the front steps and pounded on the flimsy, pressed-wood door. An odd sensation—faintly reminiscent of nerves—rumbled around in the pit of his stomach. Nothing really worried him, anymore. Except her.

He waited, not hearing a sound. But her ancient Volkswagen bug was parked out front.

Saturday night, he remembered. She could be out on a date. It was amazing, really. Cathie Baldwin, all grown up. Dating.

He swore at the image that brought to mind. A hot, summer night. No moon, but a million stars. Cathie, barely sixteen years old, jailbait if he ever saw it. With tears in her eyes, a flush of embarrassment in her cheeks and indecent amounts of pale, creamy soft skin bared for him to see.

Everything had been fine between them until that night. Cathie had been a scrawny little kid who’d once devoted herself to saving his worthless hide. He’d lived in her parents’ home from the time he was fifteen until he was eighteen, a part of them but not really one of the family, a distinction he’d always understood.

Even once he was eighteen and no longer a subject of the state’s foster care program, Mary, a do-gooder of the highest order, and Cathie kept treating him like family. During his breaks from college, Mary hounded him until he finally gave in and found himself back in the midst of the Baldwin clan once or twice a year.

It had been one of those visits, when he was twenty-three, that Cathie had thrown herself at him. As Matt saw it, he owed the Baldwins, and if it was the only decent thing he ever did in his life, he was going to keep his hands off their daughter.

He’d been doing fine until eight months ago when Cathie finally left home for college and ended up here in his town. Cathie, indulged and protected her entire life, who might as well walk around with a sign that said Take Advantage of Me. She’d always believed there was good in everyone. Even snipping, snarling, wild-eyed, would-be teenage car thieves.

One last time, he pounded on her door.

Finally, he heard the faint sound of footsteps coming from inside. A voice sounding oddly strained, called out, “Who’s there?”

“It’s Matt,” he admitted, though it certainly wouldn’t make her want to open the door. Silence. Matt grew more uneasy. “Cath? You okay?”

“I’ve got a cold. I don’t think you want to catch this.”

“I’ll risk it. Open up.”

“Matt, really. I’m fine. I was just sleeping, and I want to go back to bed.”

He pushed an impatient hand through his hair, then shoved the hand into the pocket of his slacks. Cathie Baldwin in a bed?

No, he would not go there.

“Cathie, I’ve been thinking this door really is too flimsy. I should replace it with something stronger.” He’d done all the locks when she’d moved in, but that didn’t seem like enough now. “So breaking down the door wouldn’t bother me at all.”

“You wouldn’t.”

“Try me,” he shot back, unleashing every bit of worry he’d had over her safety in those two little words.

The door cracked open. Through the narrow opening, he peered into the darkness and saw nothing more than the outline of her face.

“It’s pitch-black in there,” he complained.

“I told you I was sleeping. And now you’ve seen me. You can go.”

“Me? Or your mother, Cath? Take your pick, but one of us is going to be inside that apartment, if not tonight, tomorrow.”

“You wouldn’t.”

“We’ve been through this already with the door. You know I would.”

She fumbled with the chain lock and finally stepped back to let him inside.

He looked her over from head to toe. She angled her face away from him, hiding behind a curtain of light brown hair sprinkled with blond sunshine. It was the beginning of December, but unseasonably warm. She had on a big sweatshirt in Carolina blue, the color of one of the local college sports teams, and a ragged pair of faded blue jean shorts. He couldn’t quite make himself stop staring at the lean expanse of skin, from her thighs all the way down to bare feet and dainty, pink-tinted toenails.

Damn. Matt tugged at his tie, then reached for the tiny lamp on the table in the corner and flicked it on.

Cathie winced at the flood of light and quickly turned away. “I suppose if you’re staying, I could at least offer you some coffee.”

She headed for the kitchen. She hadn’t made it far when he caught her by the arm and spun her around. Flicking on the overhead light, he saw that her eyes were puffy and red, her face pale, a trail of tears on her cheeks.

Irritation gave way to fury at anyone who dared hurt her. He’d always been protective of her. It had been there right from the beginning, when he was fifteen and she was eight, with pigtails, gaps in her teeth and skinned knees, an optimist to the core, forced to endure both the pampering and the supreme torture of being the youngest and the only daughter in a family of four boys.

So what the hell were her brothers doing, scattering themselves from one end of the earth to the other, when she needed someone? It was all too easy, staring at her poor, sad face, to imagine the myriad of ways in which a young woman alone in a strange town could be hurt.

“Why don’t you tell me what’s upset you,” he said in a tightly controlled voice.

She stood there trying in vain to hide her feelings. Give it up, Cath, he thought. She’d always been so easy to read.

“Come on. Tell me,” he said softly, for a minute finding and slipping into that old, easy manner between them from the days when she’d been his champion, the one who could always be counted on to take his side in anything and seemed absolutely determined to draw him into the world of her big, boisterous, affectionate, nosy family. Where he would never belong. He’d never belong anywhere. It had always been so clear to him. Why she didn’t see it, he’d never understand.

“Matt, please,” she pleaded, her eyes big and wide and blue, swimming in moisture, her lashes spiked together.

Even in the woman, there were the best qualities of the little girl. She could totally disarm him with nothing but a look in her eyes.

“Please what?” he said, caught, unable to walk away.

“Please leave it alone.”

“Can’t do it.” Matt suffered from an unfortunate, long-standing urge to touch her, even in the smallest, most inconsequential of ways. Though he certainly knew better, he reached for her. Her lashes fluttered down as the pad of his thumb brushed across one of her wet eyelids, and then the other.

It was so nice to touch her.

Matt dried her tears as best he could with the back of his hand. Pale and utterly still, Cathie stood there, not even breathing, her lips slightly parted, her cheeks pale and damp.

She looked like she had that long-ago night. Heartbroken and very, very sweet. Another memory he’d tried hard to forget rushed to the surface. The feel of her lips pressed to his, of sweet, impossibly shy kisses, innocence so pure it was hard to imagine in the world he knew. She’d gotten him into the back of a pickup in a secluded valley on her parents’ farm, taking him completely by surprise, absolutely convinced that she was in love with him and that they belonged together.

He’d had a hard time convincing her they didn’t and had gotten the hell away from her as fast as he could. Okay, almost as fast as he could. He was a man, after all, and she’d practically laid herself bare on a platter in front of him. She’d been embarrassed and hurt. He’d been gruff and insulting, because she’d scared him half to death because of the way she’d tasted, the way she’d felt beneath him and the way he’d wanted her.

Should have gone to jail fifteen years ago, he thought soberly.

“What’s gotten you so upset that you’re sitting in the dark crying your eyes out?” he asked.

“There…uh,” Cathie stumbled over the words. “There’s nothing you can do, Matt. Nothing anyone can do.”

He held his breath as he asked, “Are you sick?”

“No.”

He swore softly. For a minute, crazy things had gone through his head. That she was dying. That he might never see her smiling face again. Never hear her laugh.

Of course, she wasn’t dying. She was just making him crazy, as usual.

“Not sick? Okay. What else? Flunking out of school?”

“No.”

That was highly unlikely, given the fact that she’d worked so hard to get here. Her father had fallen ill with a heart condition during her senior year of high school. His heart transplant had nearly wiped out the family financially. All of her brothers had been either in college or committed to the military, and Matt knew they’d helped out monetarily, as much as they could. But Cathie had been the only one left at home. The years she’d normally have spent in college, she’d spent helping her mother care for her father, helping run the family bed-and-breakfast, taking courses at the local community college when she could.

He knew it was still a struggle financially and held out a brief hope that this could be about money. “Need me to loan you fifty bucks until payday?”

“No,” she insisted. “It’s nothing like that.”

“Okay. You want to play Twenty Questions? I’ll play.”

“Matt, please, just go,” she said, with that quality in her voice that always had him wanting to give her anything in this world. Except this.

“Sorry, but you’re a mess, Cath. You need somebody, and in case you haven’t noticed, I’m the only one here.”

“This isn’t your problem,” she argued.

“Your mother made it my problem, and you know the way she works. If she doesn’t hear from me soon, she’ll call and ask how you are, and I’m not going to lie to her. I’ll tell her you’re a wreck, that you wouldn’t tell me anything, and the next thing you know, she’ll be pounding on your door. Is that what you want?”

“No,” she insisted. “I just need some time to figure everything out. Could you just go away and give me some time?”

It was an entirely reasonable request, and hard as it was to believe, she was an adult. But he’d didn’t think he’d ever seen Cathie looking so fragile or so hurt. He doubted he could have walked away from her now if his life depended on it.

“Sorry. Can’t do it. Tell me what’s wrong.”

She eased to the right, her hip resting against the kitchen counter, which put her face fully into the light for the first time. It looked like she’d been crying for hours. A white-hot anger simmered in his gut, and he knew he’d been asking the wrong question. Not what was wrong with her, but who? Who had done this to her?

“This is about a guy, isn’t it?” Looking utterly miserable, Cathie let her gaze meet his for a second. She blinked back fresh tears and looked away. “Want me to go beat him up?”

“It wouldn’t help.”

“I could call all of your brothers and the five of us could have at him.”

“My brothers would kill him.”

“That depends,” he said quietly. “What did this guy do to you?”

Cathie didn’t say anything. He was afraid she was crying again. Matt was considering his options when something on the kitchen counter caught his eye.

It was a small, rectangular box. Not able to believe what he was seeing, he swept past her and picked it up.

It was one of those home pregnancy tests.

In Cathie’s kitchen?

He turned to look at her. Really look. In his eyes, she’d hardly changed since that night when she was sixteen. So it always surprised him when he saw evidence that she had indeed grown up. He ran the numbers in his head. Her eight, to his fifteen. Her sixteen, to his wise-in-the-ways-of-the-world twenty-three. He was thirty now, which meant she was twenty-three.

Matt had a bad habit of still thinking of her as sixteen. This was Cathie Baldwin, after all. The good girl whose life could not have been more different from his. Matt’s hard-living, hard-drinking, never-met-a-fight-he-didn’t-like father had died when Matt was barely old enough to remember him. His mother had taken it badly, which to her meant drowning her sorrows in a bottle, too.

Matt ran wild, eventually living on the streets, headed for disaster, when he bungled the theft of Cathie’s mother’s car. For reasons he would never understand, rather than let him go to jail, the Baldwins had offered to take him into their home, something that had surely saved his worthless hide. Matt would not repay a debt like that by lusting after the Baldwins’ only daughter.

Besides, he’d always known what life had in store for her. A nice guy. A really nice one. Respectable. Wholesome. Not a single skeleton in his closet. Not a single arrest. Someone from a good family. Not necessarily well-to-do, but kind, God-loving people. She’d have a nice little house in the mountains her family called home, teach Sunday school and raise a half-dozen kids, and she’d be happy and well-protected her whole life.

But it hadn’t worked out that way. Another man had slept with her. Carelessly? Casually? Thoughtlessly? And that man had either failed to take the time to protect her or hadn’t cared enough to do so.

Matt held the proof in his hand.

He crushed the box of the home pregnancy test in his hand, taking out a mere shred of his anger on it, then threw it across the room.

Cathie winced as the box skittered across the floor, then opened a drawer and pulled out a white, plastic stick-like thing. “I’ll save you the trouble of asking. The stick turned blue.”

Blue? he thought numbly. “Blue’s bad?”

She nodded hopelessly. “If you’re not finished with college, not married, don’t have a lot of money and your father happens to be a minister, then…yes, blue’s bad.”