Читать книгу Kama - Terese Brasen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSLAUGHTER MONTH KIEV 934 CE

Kama opened Mother’s silver box. Flat glass decorated the lid. Lines of gold connected the orange, blue, green and red pieces. Hinges held the lid open. Inside was a glass mirror and small cups of colored powder, red creamy paint, charcoal sticks and brushes. All seemed new and almost untouched.

Everyone was preparing for the long cold ahead. Animals were sacrificed every day. The ice had closed in. Father would wait now in Kiev until the river melted. Every day Mother brewed her concoction. She blended yellow and crimson powders into a bittersweet broth with almonds and figs and chickens. She tried to lure Father back with the irresistible broth. Every day she sent Kama to the Big House with a jar for Father. Kama hated these errands. Often he was still in bed, and she would leave the container outside the chamber, and then pick up yesterday’s jar, knowing that this could go on and on all winter.

She always debated what to wear. Should she dress in finery, just to prove she was Kama, Sigtrygg’s daughter, and had the judgment and grace to be a princess? Would arriving in a lavish dress demonstrate how absurd and out of place Father’s demands were here, where there were no kings and queens, just hunters who lived in huts? Father referred to the Norse people as ‘those who eat with their hands,’ contrasting the Vikings with the east where forks were the norm. He wanted Kama to learn refinements, not fall into this crude, sub-standard way of living, but this was all Kama really knew, and she had difficulty understanding the nuances that characterized “refinement.”

Today Kama had decided on a temple ring. Would he behave better with witnesses around or would he bash her about publicly? If Father were still asleep when she arrived, she would wait and present herself as a tribe’s woman. She would stand up to him and say, You can’t tell me how to behave. I’ll decide who I am. She had gathered a collection of temple rings and planned to show off a new one every day. Now she was shading her lids with blue, drawing thin dark circles around her eyes, smearing red on her lips and rubbing color into her cheeks. When she was done, she would carefully place one of her newly purchased temple rings over her forehead. She would complete the costume by adding a fur-trimmed vest stitched with pictures of birds and wolves.

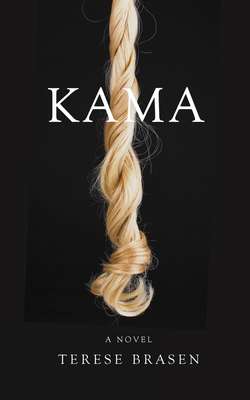

Kama prepared. Mother’s aromatic stew bubbled. Kama sat at Mother’s sewing table and used the small vanity lid to scrutinize her work. She braided her hair, partitioning it into sections, twisting each into a circle and pinning it in place. She wished she had asked for help from one of the tribe’s women who knew this old and characteristic way of parting and arranging. She completed the plan inside the bed closet. There she pulled on knitted stockings and then a dress that was actually two parts, a bottom that hooked at the waist, and a top that tucked in.

Mother had paced all morning, singing, although a little out of tune. The high notes seemed too sharp and the tempo erratic.

Finally, Mother called, “Can you come now?”

When Kama stepped out of the closet, Mother was standing, holding the jar by its handle, ready to pass it on, so Kama could begin her errand to the Big House, but then everything was wrong, and Mother was shouting, “You can’t go out of the house like that!”

“Like what?”

“Like a slut,” Mother said, using the Norse word for mud and dirt.

“You’re the slut,” Kama said. She yanked the stew from Mother and slammed the door behind her.

Kama didn’t run, afraid to spill her delivery, but she was walking very quickly with long forceful steps, her thoughts preoccupied with the moment of glory when she would pronounce her defiance to Father. Then a small body slammed into her. The woman was running so fast, she couldn’t slow down.

“You’re Kama?” she said. She had short hair and a body the size of a child’s, but she was a grown woman with worry in her eyes.

“I’m Kama,” she answered, disappointed that even this stranger had recognized her.

“You must come,” she said, pulling her arm and pointing toward the Big House. Kama didn’t ask, just followed, hurrying to keep up. The woman took Kama’s jar, showing she was a servant accustomed to taking care of other people’s chores. She led her to Father’s back room. On the bed lay Father, but he had become an old man, face was covered with red sores. A compress covered his forehead, a sign of fever. How many days had it been since Kama had seen him? How many days had she simply left the jar and returned home?

“He will die,” the woman murmured, and Kama asked, “Who did this?” Men did not die from mysterious illnesses. Swords and axes took their lives.

“No one did this,” the woman replied. Then Kama saw a dish on the floor. Father had clearly pushed it off his bed. Spilled broth had begun to dry. Stew. And in the corner nearby were two dead mice. Poison. The room smelled like Father, which to her was always a clean scent, because despite his days and months onboard ship, he fussed over his appearance. He traveled with regular men but could never hide he was a prince who expected ceremony and needed to be prepared for the extraordinary, because a bard may choose to record the moment, and however he described Sigtrygg could become a lasting record. Even with his skin cruelly marked and his magnificence waning, no one had looked past the face and body to see that the wooden space was littered with dead vermin.

The servant had placed Kama’s jar on the bedside. Kama threw it off the table. The jar banged against the wooden floor, the poisonous broth spreading across the planks.

Kama had no words for what she felt. Sad, unhappy, afraid—none would reach far enough and explain the unthinkable. Don’t try to understand. Plan a course of action. Her reaction was partly a response to Mother who could never act but cried instead when facing adversity. At first, Mother’s worries had been small and immediate. She would wait at the door, peering through the shutter, watching for Kama or Father, forgetting he was always late, fearing more when the ice was closing in. She imagined the worst, Father dead, captured by pirates, his ship capsized—any number of horrific incidents. Terrible things happen, and life’s events can be worse than any imaginings, but Mother seemed unable to understand the futility of worry, which annoyed Kama and left her impatient with her inability to quiet one’s own thoughts. Mother was a child who imagined dragons and monsters. Kama tried to hold every fear inside an iron clamp, thinking even the smallest uncertainties would turn her into Mother. Mother could never step out of her own emotions long enough to understand how small her pains were.

Then Kama wiped away that thought. Mother had clearly acted. Decisively. She had planned and acted. Kama could not trust her own judgments. She had never known her own mother. She had made assumptions, because she felt confined by this woman who wanted to trap her inside the townhouses with useless women who told the same stories and shared the same worries every day. If Kama had known what was taking place, she could have intervened, but instead, she had carried Mother’s poisoned pots. Perhaps some one would think Kama had done it intentionally.

But who had helped Mother? Where had she found the venom? How had she known how to flavor a stew to hide the taste? Was this a skill she had learned in the convent in Constantinople? Was this how the women in the nunneries found their revenge and regained their honor? Was this Mother desperate and afraid to be left alone, because all she had was Kama and Father, and she knew she was losing both? Could Mother even think that clearly? Had she planned to murder her too? Had Kama eaten from the same stew?

Kama ran from Father’s room to the townhouses.

Desperately, she twisted the handle and banged her fist, listening for the shuffle of footsteps. Kama continued to bang until finally the door swung open. Standing in the doorway was a silhouette with dancing eyes. At one time, Mother's world had been refuge from the cold and dark, but now new dangers lurked here. Kama needed to start somewhere. Take control. Take charge. Introduce order. Perhaps she would remember a conversation or a phrase that would tell her what day it was. She wiped her tribe’s woman costume from her face, then began opening her braids. Her hair reached as far as her lap now when it hung loose. She noticed too it was darkening with black among the blonde. At one time, she had thought it would turn black like Mother’s. She had imagined herself tall with green eyes and exotic black locks. But that day never came, and today she only wanted to pull out each and every dark strand.

“Remember the garden,” Mother would say sometimes now, staring out the open door into the courtyard, bare-branched trees looking like spider webs against the gray sky. Kama and Mother had never had a garden, but Mother wasn’t talking about an ordinary, everyday orchard. She was dreaming of a better world.

“You have no idea how I miss it,” she would say. “Everything was beautiful. Fruit everywhere and sunshine. Adam and Eve were happy. They ate food without having to plant it. Their bodies were one. They loved without touching.”

Why hadn’t Kama sensed that these weren’t just ordinary wishes, but signs of a mind rotting, like wood turning black from worms and too much moisture, like cheese turning to mold, the blue slowly overtaking the white until the original no longer existed. Mother’s god invited people into the silent darkness of their own minds, and Mother had become lost in there, convinced she had a separate being inside her, something she called a soul. Someday god would set it free. But gods care only about themselves, and all Mother’s prayers would never stop Loki from playing and upsetting her best-laid plans.