Читать книгу Jeet Kune Do - Teri Tom - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD BY TED WONG

Оглавление"True refinement seeks simplicity." —Bruce Lee

At different times and in different places there suddenly appear individuals who produce something completely new in their chosen fields. Whether in science or art or sports, they have the confidence to go beyond the known and predictable, to arrive at something entirely different from what went before. Bruce Lee, in his short life, boldly pursued one thing, an original martial art. What he developed was a revolutionary style of unarmed combat, and it was an art only, and immediately, original to him: not a derivation, not a combination, not a collaboration.

To Bruce Lee there was a profound difference between his JKD, and all other martial art disciplines. The fixed nature of traditional martial arts was, he thought, unworkable—methods too busy, too complex, and too rigid to be strong. He did not want superficial strength. The strength he wanted would come from a scientific approach to gravity and weight, efficiency and balance, force and speed. Driven to create a singular style, Lee placed the full-control of what he was forming in the hands of the only person he completely trusted—himself. He drew on his own character—his instincts, his physical conditioning, and his forceful intellect to communicate the distinctiveness of his art. Refined mechanics, exacting execution, incredible power—this is JKD.

Only one individual, Bruce Lee, truly created and shaped JKD, and only Lee completely brought it to life from his personal conviction, determination and vision. But nothing comes from nothing—there is always something that precedes. Lee did have inspirations. They were not, however, of Eastern origin, but Western fighters: boxers Jack Dempsey and Jim Driscoll, and the fencer Aldo Nadi. Studying them reinforced Lee's definition of his own method. He made JKD basic principles few in number, but adaptable and dependable under any situation. Less being more, Lee emphasized disciplined, simplified positioning and movement, supported by effective analysis of diverse circumstance.

Embodied by Bruce Lee in his lifetime, the truth of his art is clearly evident in Lee's films, his interviews, and especially in his writings. It is outrageous, then, to suggest that JKD is an extension of another discipline—a suggestion that runs completely counter to his life and work. And it is insulting to see JKD deemed by some as obsolete or so weak that it requires additional techniques to sustain it—a characterization which subverts Lee's significant form of unarmed combat. Let me state this plainly: no student of Lee's has surpassed him; no one knew better than Lee what he was doing and why; no one is qualified to alter Lee's work. Bruce Lee created JKD. Add something to it, or take something away, and you are doing something other than what Lee taught.

I first met Bruce Lee in 1967 at his school in Los Angeles' Chinatown. Even before our meeting, however, I knew him from television, in his role as Kato on The Green Hornet. Lee's Kato was like a cat—quick, graceful and powerful. His appeal far outshone that of the show's hero. Never had an Asian character been portrayed in Western popular culture like Lee portrayed Kato—tough, cool, confident. It was the beginning of Lee's iconic celebrity as the first Asian superstar. It is easy now to forget how unique Lee was. Martial artists are everywhere in the popular culture today, but forty years ago there was only one: Bruce Lee. Even with Asian stars such as Jet Li, Steven Chow and Jackie Chan, and with incredible advances in special effects, which allow anyone to look physically amazing on film—Bruce Lee remains without peer. His image and style still resonate with compelling effectiveness.

The first time Bruce Lee ever spoke to me, in our second class, it was to demand: "WHO ARE YOU?" There had been a mix-up with my registration. After I explained, we started to talk in Chinese, and found that our similar upbringings had given us things in common. Yet standing next to Lee, there was no similarity between us whatsoever. I was a skinny, reserved young man. I had no martial arts training, but was instead a kind of blank page, which, perhaps, was my biggest asset. Like a "mad scientist" with an experiment, Lee could mold my understanding, and completely shape my experience. The first thing he did was to have me buy weights and start on a regimen to develop physically. Then within a short time, I began private lessons at his home.

Going to classes at his school, and then, privately training, gave me a unique opportunity to observe the formation of Lee's art. The school's classes were practical and formulaic, devised around a curriculum of modified Chinese kung fu, necessary to impart discipline on a large group. But the class bore no similarity to Lee's private lessons. There, Lee was in a different zone, teaching a kind of free form, experimental course in his developing art. Increasingly, he was content to instruct privately. Seeing the school's curriculum as outmoded and unrelated to his work, he closed the school. He did not care about establishing a commercial venture, but instead, turned towards achieving a discipline.

In private instruction, Lee completely oversaw the dissemination of his theories and techniques. Some students received different levels of instruction than others, different degrees of what he knew. Evolving rapidly, he demanded precision from himself and expected students to follow without argument. He explained little, and had scant patience for repeating what he demonstrated. If you didn't get it quickly, then you were out. As he expanded his techniques, Lee kept most of the mechanics in his head, always reserving something for himself—a knowledge that made him the "master of the art." He was not about to impart "the keys to the kingdom" without their being justly earned.

Lee's mechanics were as much rooted in the intellectual as the physical. To fight like Bruce Lee, one had to learn to think like Lee. I was one of very few people taught by him directly—training, sparring, and "hanging out" for seven years. By listening closely and watching attentively, I began to be aware of the underlying precepts of JKD. For 15 years after Lee's death, I continued to study the structure of his form. And for 15 years after that, as I implemented what I learned, I discovered even more. JKD consists of few techniques and is without a lot of show or flash. Kicks and punches are concise, defined with form following function. During his life, I admired Bruce Lee and deeply appreciated the skills that he taught me. Since his death, I have honored him. Every lesson I teach, I ask myself, "Would he approve?" With every problem I encounter, I ask, "how would he approach this situation?"

I deeply regret that at the time of Bruce Lee's death all his students did not come together to pool knowledge and form a united front to continue his work. Sharing, discussing, perhaps arguing, we might have arrived at some common ground to go forward, and attempt to systematize JKD at that time. The force of Lee's personality had connected us when he was alive, but when he died, we all went our separate ways. Since then, I have seen wildly inaccurate interpretations of JKD. Some stray from and others even contradict Lee's intentions. It pains me to see his legacy undermined by perspectives skewed or self-serving. Never, in the time I knew him, did I see him collaborate with anyone, nor did I see him base his work on elements from other martial arts. Today, there are all sorts of schools and all sorts of instructors who claim to be teaching Bruce Lee's method—there is nothing in them that I recognize as his.

I hold fast to what I learned; I vividly remember Lee's words and actions. Though I have never advertised, or had a school, I have been a private instructor for more than thirty years. Individuals from different countries and backgrounds have sought me out for instruction because of my direct line to Bruce Lee, and I have shown them the essence of what I was personally taught by him.

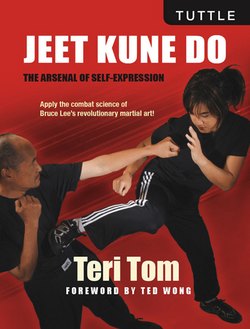

As I was Lee's devoted student, so I consider Teri Tom my student—my top student. For over ten years, she has spent more time learning, discussing and investigating the fundamentals of Lee's art with me than any student with whom I have worked. Her attentiveness in developing the discipline accurately, and her devotion in seeing it raised to the level that Bruce Lee envisioned in his life, heartens my belief that through her, the art I learned and teach will be passed on to future generations.

It is tragic that the art that defined Lee—one he nurtured, guarded, and methodically shaped and executed—continues to be misunderstood by so many. It is my deepest hope that Lee's art, as he taught it, will once again, with Teri Tom's excellent new book, be studied and appreciated. She has explored Bruce Lee's writings and examined the sources of his inspiration. Here she offers an impeccably researched, thorough and realistic presentation of Lee's art and its application insuring that the discipline he developed in his short life, will not perish from misguided egos, insincere motives, or plain stupidity. By placing Lee's art in proper perspective, Tom challenges all the absurdities being espoused in his name. I believe Lee would see in her, as I do, an intelligence, resolve and courage similar to his own. Plainly stated what Bruce Lee taught and practiced is contained in this book.

—Ted Wong, November 2008