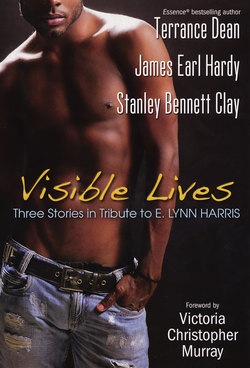

Читать книгу Visible Lives: - Terrance Dean - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A Tribute

ОглавлениеBy Terrance Dean

Originally published in The Advocate magazine,

September 2009 issue

In the summer of 1992, I’d just graduated from Fisk University in Nashville and broken up with my girlfriend. I went to Atlanta with some of my down-low friends to hang out and explore the burgeoning gay scene in the rising black metropolis. While at our host’s apartment I saw a tattered book on the coffee table. The title, Invisible Life, immediately leapt to my attention. For the next six hours, as I sat engrossed in this novel, the sounds of talk and laughter all around me receded.

I hung on every word. Page after page, I consumed the intricate life of the protagonist, Raymond. His life was so much like mine. He was confused, angry, sad, forever asking, “Why was I this way?” I couldn’t help but wonder who had taken a peek into my own secret life and put it in a book.

I frequently turned the book over to read the title and author’s name, E. Lynn Harris. How did he understand how it felt to be caught like this, between two worlds, heterosexual and homosexual? Like Raymond, and like thousands of men, I later discovered, I felt like an anomaly. There were so many of us, and we all felt uniquely burdened and isolated. But, that summer, after reading Harris’s breakthrough novel, I felt I was not alone.

Seventeen years later, while driving from Detroit back home to New York City on July 24th, I received a message on my BlackBerry from my publisher stating, “E. Lynn Harris died.” Shocked, I immediately called. My fingers trembled as I pushed the numbers on my cell phone. What was this nonsense about E. Lynn dying? He couldn’t be. I had just heard from him earlier that week. He was in good spirits. My publisher confirmed the message, “Yes, sweetie, E. Lynn is dead.” I burst into tears. I screamed. I couldn’t focus on the road. I pulled off in a rest area and wept. I cried for my friend and mentor.

I met E. Lynn in 1999, when I invited him to be a featured guest at an event I was organizing at the Harlem YMCA. “Of course I will come,” he said at the time. “It would be my honor.” Gracious, humble, accommodating—three attributes I would come to know as integral parts of his character.

I was unprepared for Harris’s fan base. Women lined up, out the door, and around the corner of our small room at the Harlem Y, to meet him. He smiled, shook hands, took pictures, and signed many, many copies of his books without complaint. Black women loved E. Lynn. For the first time he gave them a glance into a hidden world of intricate and compelling love stories between athletes and professionals, gays and men on the down-low. Black men loved E. Lynn, too. His novels told our stories, in our words. He was a trailblazer, a pioneer. And, whether he recognized it or not, he carved out a unique literary niche that made publishers take notice.

He embodied the Harlem Renaissance, the spirit of the social activism of James Baldwin, the cunning and wit of Langston Hughes, the romance of Countee Cullen, and the ingenious storytelling of Zora Neale Hurston. He became the voice of the black gay community, and because of his books we were all talking about the new phenomenon to which he had introduced us. His writing about the down-low sparked a national dialogue.

In August 2003 the New York Times Magazine wrote on the topic and the floodgates opened. Magazines, newspapers, even Oprah, all dove in. E. Lynn had created a sensation but he never took credit. He merely said, “I just want to write books and tell stories that are personal to me.”

His courageousness helped to open the doors to other black gay writers such as Keith Boykin, James Earl Hardy, Stanley Bennett Clay, Fred Smith, J.L. King, Lee Hayes, Rodney Lofton, and me. Harris also influenced female writers—Zane, Karen E. Quinones Miller, and Victoria Christopher Murray—to include gay and down-low characters in their works.

E. Lynn was a movement. Before he died from a heart attack in his hotel room in Los Angeles, he was gearing up for the promotion of his newest book, Mama Dearest, and had just met with a television producer. I’m told he signed over the rights to his books to be developed for TV.

My introduction to E. Lynn, Invisible Life, was the book he had self-published and sold from the trunk of his car to salons and beauty parlors in Atlanta. Since then, ten of his books became New York Times best sellers. The publishing world was once nearly void of contemporary black gay literature. Now it’s filled with over four million copies in print by Harris alone.

Over the years he often encouraged me to not be afraid to share my voice. “Boy, you got a story to tell,” he would often say. “Don’t be afraid to share it. There are many men just like you who would benefit from your words.” Like few others who’ve walked this earth, E. Lynn knew the power that comes from telling our stories. He will be missed more than he could have known.

I miss you dearly!