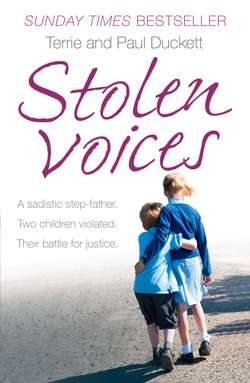

Читать книгу Stolen Voices: A sadistic step-father. Two children violated. Their battle for justice. - Terrie Duckett - Страница 6

Chapter 1 ‘Humble Beginnings’ Terrie

ОглавлениеMy parents, John and Cynthia, were childhood sweethearts. Their relationship had begun like a storybook romance, but with their marriage their dreams died.

Mum intended to follow in her father’s footsteps in Northampton’s traditional calling, designing shoes, until she naively showed her designs to a local shoe manufacturer during one lunchtime, who stole them. Dad joined the parachute regiment and aspired to be part of the SAS – until he failed their selection course.

In 1968, with both their dreams in tatters, life was to change irreparably again. Mum discovered she’d accidentally fallen pregnant. To say Dad was not best pleased was an understatement, but in 1968 pregnancy meant marriage and that was that. So Mum abandoned her place in college and went up the aisle – or at least the corridor – of Northampton register office.

She didn’t tell her parents, my Nan and Pap – Gladys and George – at first. Not only had she let them down, but they believed she could do better than my dad. However, by the time she told them the damage had been done, and at the very least they felt he’d done the honourable thing.

I arrived on 27 June 1969 in Aldershot, the garrison town where Dad was based. For the first month of my life we lived in married quarters, though Dad was desperate to be released back to Civvy Street, not being able to face being returned to his parachute regiment after failing the SAS selection course. The only way he could be discharged was to buy himself out, so Mum raided her savings and stumped up the required £200 – a prohibitive sum, but a small price to pay to keep her new husband happy.

Mum and I lived my first year with my Nan and Pap in their cosy two-bedroom house. But the first home I remember clearly was a council maisonette in Moat Place. It was a bit sparse; the kitchen and lounge were downstairs and the bedrooms were up a white-painted stairway that had a thin carpet runner tacked loosely to the wood. Two wooden slats ran down the side of the stairs, with a narrow gap between them, so that as a small child I could peer through. I spent a fair bit of time sitting in nervous silence on those stairs, listening to Mum and Dad argue their way through life.

Dad worked away a lot of the time, stopping home for clean clothes and food maybe once a fortnight. When he wasn’t there to argue with Mum, I felt happy and relaxed. I had my mum all to myself and we had our routine. We didn’t have a lot of money, or many belongings, but she had time for me – even though I could be more of a hindrance than a help, as a simple trip to the shops could turn into an adventure.

At the age of four, whilst I was dawdling back from the shops with a loaf of bread for tea, I thought of Hansel and Gretel. ‘I wonder what would happen if I dropped a trail of bread slices?’ Imagining a magical creature might appear, I pulled slices of bread out of the bag and began placing them carefully on the pavement. Skipping along, I looked over my shoulder, pleased at the snowy trail … until Mum suddenly appeared, looking up the road for me. ‘Terrie!’ she cried. ‘What are you doing? That’s our tea!’

I held a slice of bread mid-air and my face crumpled. ‘Sorry, Mummy.’

She scurried to scoop up the slices and put them carefully back into the bread bag for later.

The weekends Dad came home left their impression on me. One such weekend, when I was three, I was sitting in the kitchen waiting for Mum to dish up dinner when he arrived. I looked up as he walked in, but he didn’t seem to notice me.

‘Hurry up, I’m hungry,’ he complained to Mum. Mum seemed flustered and rushed to place the plates of macaroni cheese in front of us. ‘Is this it?’

Mum looked up. ‘I have some Spam if you’d like some?’

He laughed sneeringly. ‘This’ll do.’

I was actually relieved. I hate Spam – no, I detest Spam. Poor Mum was running out of new ways to cook it. Fried, battered and deep-fried, diced and sliced. For me any way was disgusting, and I would often gag trying to swallow the pink sludge.

I hated macaroni too. I couldn’t stop thinking about slugs as I tried to swallow the slimy pasta pieces. Dad would become frustrated with the faces I was pulling and send me up to my room, telling me not to come back downstairs until they had both finished dinner.

A few minutes later, as I cautiously slid back down the stairs on my bum, I could hear our budgie was squawking loudly. Dad was standing up shouting as Mum turned to look at me. He followed her gaze and saw me. ‘Get out! This is adult talk. Get out, now!’

I ran and sat on the stairs, scared and alone, peering through the gap.

At three years old, I was confused. I still wanted and needed to be loved by my dad, but I felt anger towards both of my parents for letting him come home and ruining my time with Mum. The rage had to get out somehow, so I began destroying things Mum had lovingly made for me. I picked apart a crocheted waistcoat made with squares of colourful pansies all sewn together. I cut the silky lining out of the green felt coat she’d made. And I carefully hacked my way across my fringe.

Dad’s presence at home meant rows and arguments, slammed doors and tears. Mum never really explained why it happened; I just thought it was my fault, because I was stupid and ugly.

It may have been that Dad felt trapped at home and would rather have been back amongst the camaraderie and banter of his army friends. Dad had joined the Territorial Army after being discharged out of the service, as it was more relaxed than the regular army. I enjoyed watching him with his mates in the TA, laughing and joking, so very different to how he was at home. Drill weekends often included family gatherings, lots of delicious food and kids running about, playing games amongst the lorries and heavy gear outside the drill hall.

But Dad did let a glimmer of his home face show there occasionally. Like the time he was supposed to be keeping an eye on me while Mum was inside with the other mums setting up for dinner. I was on my hands and knees pushing my new green plastic train that had two carriages attached. He warned me not to go near a large stack of bricks by the wall, but, me being me, I pushed my train a little hard. It sped off behind the brick stack. The top of the pile was leaning in towards the building, but there was a me-sized gap between the stack and the wall. I squeezed between and reached out for my train. I heard Dad yelling just before the pile fell onto my legs.

As he yanked me out by my arm, I said my leg felt funny and I refused to stand on it. ‘You’re just being a baby,’ he said.

I cried and he yelled for my mum. She gave me a look over and said I needed to get my leg checked. Later that day, as I showed my broken leg, plastered to the knee, to my Nan, she was horrified. She gave me extra cuddles to make up for it.

To me, Nan and Pap were perfect. Their house was an oasis of calm and I loved every brick of it, from the Indian-style felt-covered living room, where Nan saw faces and shapes in the patterns (‘Look, Terrie, there’s a goat!’ she’d laugh), to their conservatory where Pap would proudly show off his small cucumbers hanging around the door.

Nan had blonde wavy hair and sweet, flowery perfumed skin. She was always quick to cuddle me whenever she could. Nothing was ever too much trouble, whether it was cooking up delicious treats in the kitchen, playing pretend games or re-telling every fairy story I could absorb. Nan would pull up a chair in the kitchen, so I could stand and help her make dinner. Afterwards we’d play snap, or she’d get out a big tin of assorted buttons she’d collected over the years and we’d sit and thread them onto coloured cotton.

Pap was as round and cuddly as Nan, and they adored each other. He always had a twinkle in his eyes when he told me stories of when he was a boy and how mischievous he was.

All too soon, it was time to go home.

In late 1973, I was holding Mum’s hand as we walked across the Northampton market square, when she turned and knelt in front of me.

‘Mummy is going to have a baby.’ She looked a little worried, patting her tummy. I’d seen it getting rounder and fatter.

‘Okay.’ I shrugged, not really understanding. It was obviously something I was thinking about, though, as later that afternoon I pointed to Nan and Pap’s tummies. ‘Are you both having babies too?’ They laughed.

That evening I played with my only dolly, Baby Beans, named because she was filled with dried beans. I could hear Mum and Dad downstairs, and he didn’t seem happy. I tried banging my head against the wall to block out the sound of their voices. It didn’t work, but I did eventually manage to fall asleep.

When I woke in the morning, Dad had gone again for a few weeks. Mum heard me stir and called me into her bedroom. ‘Hey, Ted,’ Mum said, using her nickname for me. ‘Come and put your hand on my tummy.’

She held my hand firmly to her stomach, and I felt something move under the skin. ‘That’s the baby’s foot,’ she said, her face lighting up.

I looked at her big belly in confusion. ‘How did it get there?’ I pointed to her belly button and she laughed.

A couple of weeks later I was taken to Nan and Pap’s. ‘The baby is on its way,’ Nan said gently, ‘so Mummy is in hospital.’

I worried. I didn’t really understand what was happening. But the next morning Nan took me on a bus to the hospital and held my hand as she led me to a bed where Mum lay, looking exhausted but happy. As we reached the bed, Nan lifted me up so I could look into the crib. There was a little baby with a screwed-up pink face, swaddled in a blue blanket.

‘Isn’t he lovely?’ said Mum. ‘His name is Paul. He’s your brother.’

I grabbed Nan’s hand again. Everything seemed too strange, and I tugged at her to leave. I’d had enough of Paul already. ‘I don’t really want a brother, thank you,’ I said as politely as I could.

Mum was in hospital for a few days, after which Nan walked me back home. I tried not to cry as she knocked on the door to our house. As we entered everything smelled different, the house seemed messier and it didn’t feel like home. Nan gave me a kiss goodbye and headed home to Pap. I ran upstairs to my room and cried; I’d desperately wanted to go back with her, but dared not say anything.

The next few weeks were filled with nappies, washing, bottles and crying. Gently I stroked his fuzzy peach scalp while he was asleep. I was growing to like him. He always seemed to like me reading my picture books to him, so perhaps having a baby brother wasn’t going to be so bad after all.

Dad hated Paul crying and escaped out with his friends as much as he could. Tired from night feeding, Mum would let me take Paul out by myself in a big second-hand Silver Cross pram she’d borrowed. I proudly paraded him to my friends. ‘He’s my brother,’ I said proudly. ‘And it’s my job to look after him.’

Starting primary school gave me a chance to show off my reading skills. I loved going to school, though I did hate leaving Mum and Paul alone. I was used to having Mum’s time; now all of a sudden I had none.

Eventually we moved to a new council house in Churchill Avenue. Mum wanted us to go to a better school and live in a nicer area. The house was much bigger, with room for Paul and me to run around. By then Mum worked all hours, doing day and night shifts in a shoe factory. She always groaned when the bills arrived, and while Dad worked away we never had much food in the cupboards.

Mum walked me to my first day at lower school, only the second time she ever took me. I hated the mornings before school. My long hair was always knotted and tangled, and Mum had to yank the brush through. By the end of lower school Mum had had enough of the morning battle to brush my hair, so she placed a bowl on my head and cut around it.

I looked like a boy. I hated it. I clutched at my head, wondering what had happened. From that point on my hair was always kept short, Mum cutting it herself in the kitchen. ‘I’m not very good at this,’ she sighed. ‘But it’s just easier this way.’

The kids at school laughed at my hairstyle. They taunted me for having a boy’s name and tatty hair. At the age of six, I realised I didn’t fit in. My clothes were threadbare and my shoes worn to the sole. I was never invited back to anybody’s house for tea.

The closest person to me was my little brother, and I loved playing with him. He’d grown into a mischievous, adorable toddler with a mop of blond hair and a cheeky smile. He tried to follow me everywhere on his little red tricycle. He was always looking for attention from Mum – I’d just got used to not having any. In the evenings, if Dad was away, we’d be passed between babysitters and Nan and Pap while Mum worked until 9 p.m. But although Mum worked a lot, she, Paul and I were happy together.

Despite my age I could sense Mum and Dad’s marriage was falling apart, but occasionally we were able to pretend we were a happy family. At family barbecues or at TA events, sometimes Dad would chase us around with water pistols, laughing, and for a few minutes I could pretend everything was okay at home. On occasion he would surprise us all. Once he turned up after a few weeks away with a puppy, a beautiful tortoiseshell-coloured mongrel. We decided to name him Sam. We all loved him. Another time he brought us the biggest hand-made Easter eggs I’d ever seen.

I was eight when we met Dad’s friend Peter Bond-Wonneberger at one of the TA functions. Peter was in his early thirties, with dark hair brushed to the side and a wiry moustache. A smiling, happy guy, he always seemed up for a joke or laugh. He was married to Anne and they didn’t have kids. Anne didn’t seem that comfortable with our energy and playfulness, like Peter did.

‘Hello, Terrie and Paul!’ he beamed and crouched down to our height whenever he saw us. ‘Want to have a look at my camera?’ Peter was always snapping away.

Sometimes I wished Dad was more like him. Often they went off together to the TA Centre to develop photographs in a lab. Sometimes we were allowed in and saw them hanging on the line, dripping and smelling of chemicals.

Dad had gone off on a trip to Zimbabwe to see an old army friend, and asked Peter to pick him up from the airport. Peter arrived to collect us first. He was in a chatty mood, as usual, pulling on our seat belts, making sure we were comfortable.

‘What planes you hoping to spot, Paul?’ he asked.

‘Big ones!’ Paul giggled.

‘Great! I’ll get a shot of a jumbo for you,’ he replied.

It felt good to have an adult, especially a man, showing interest in our lives. On the way back we stopped off at Dunstable Downs for a breath of fresh air when Peter pulled out a cine camera.

‘Wow!’ said Paul. At four he didn’t quite understand it, but was impressed by all the buttons.

‘Hey, I know,’ said Peter with a huge grin. ‘Why don’t I take a film of both of you, eh? You can act, can’t you? Be fun to see yourself like in the movies!’

Mum and Dad laughed as Peter concentrated through the viewfinder, and Paul and I sprinted off, dancing hand in hand. I was in a light green dress with big sleeves that made me feel girly for once, despite my cropped hair.

That afternoon, Peter captured a rare moment: us, a happy family on film. As our mum and dad held hands, watching their giggling children playing in the fields, for half an hour we were genuinely a family.