Читать книгу Dirt Farmer's Son - Terry A. Maurer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter II

Military School (1950–1956)

Harry S. Truman (1945–1953)

One day in early September 1949, I heard Dad telling Mom that the boys (my brother and I) would be going to a Catholic military boarding school in Monroe (Tony was eight and l was six). My mom cried and replied, “No, they can’t go.” My dad said that the decision had already been made and that we would be leaving in seven days. He told my mom that Uncle Doc would be paying the tuition ($500 per year for nine months room and board—a lot of money in 1950), and the boys would get a good education, better than at the public school in Frederick. Also we would not need to ride the school bus seventy-five miles per day anymore. He then called Tony and me to tell us the news. I remember Dad saying, “There will even be kids from Detroit at this school,” as if that would impress a six-year-old like me. But I could tell by the way he said Detroit that it meant something to him.

Pauline, Louis, Tony, Bernard, and Terry in 1954.

We drove to Monroe, probably in Uncle Doc’s Buick. We only drove that two hundred miles two or three more times in the next thirty-one round trips, which I made over the next six years. It was always the midnight train from Roscommon with a four-hour layover in Detroit’s Grand Central Station and the same in reverse when coming back to Roscommon for the Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter furloughs. We got to know every inch of Grand Central Station’s ground floor. We saw the trains go from the transportation of choice with its fancy conductors in uniform and clean seats with fresh white paper-covered headrests on every seat to something less by 1956.

I continued to ride the trains from 1956 to 1961 when I went to high school in Holy Trinity, Alabama, and then first year of college in Monroe, Virginia. For sure, by 1957, one could observe the decline in service and less attention to detail in all areas of train travel. The era of air travel was getting started for not just the rich but even for some of the privileged poor. That’s what I thought of myself. I didn’t get on a commercial plane until I flew to Mexico City in 1962, but one could see that the passenger trains were not the future.

The first night at military school was memorable. I was assigned to one of the special tower rooms with its one-foot window ledges and eerie tall ceilings. It held four students. There was a big thunderstorm passing through as we heard “taps” for the first time, and then I could hear my bunkmates crying. I am not sure if they were scared of the storm or scared of being alone away from their parents for the first time. I don’t think I cried. I would always cry when I saw my parents. Tony would always cry when he left them. Neither of us cried at the same time. My parents told me they were going to be spending the night with Uncle Doc’s aunt in the city, so I knew they were not too far away that first night. School got started the next day, and I did not see any parents again until Thanksgiving vacation nearly three months later.

Third grade was the year that most of my classmates started classes at HDC. Mike Sweeney started in first grade, but my best friends, Cadets Paul Ewing, Dennis McIntyre, Eugene Willis, Paul Hebert, Tim Gillet, and John Vandegrift, started with me in third grade. Gordon Rebresh started military school in the fifth grade. Sweeney was also one of my best friends. He and I were altar boys together, and in sixth, seventh, eighth grades, we were always paired up to do the serving for the annual first communion mass, usually for the second graders.

I remember thinking I was too old to play in the sandbox with some of my classmates who thought it was really cool. We never had a sandbox on the farm—who needed a sandbox? There was dirt everywhere—but I did fall asleep in the chicken yard once and woke up when a rooster pecked at my bare feet.

In 1950, we learned to play soccer. Our fourth-grade nun, Sister Thomas Ellen, had a brother who was a professional soccer player, and she knew all the rules. I also saw the movie The Pride of St. Louis about Jerome “Dizzy” Dean, the St. Louis Cardinal player who won thirty games pitching. I started pitching then and didn’t stop until 1960. I even got Denny McClain’s autograph with my son, Stephen, when Denny won his twenty-eighth game for Detroit in 1968. Denny finally beat Dizzy Dean’s record by winning thirty-one games that year. I thought I was so good that I even took my confirmation name in 1954 after Mr. Dean. The name was Jerome. My first grading period in third grade was not pretty. I was a straight-A student in Frederick, but at HDC, the nun said I was so far behind they wouldn’t embarrass me with a grade for any of my classes.

I don’t remember much about that first summer back home. However, I was ready to go back to Monroe for fourth grade. I did and I improved in my classes, and I was made a corporal that year. Maybe it was even sergeant. Sister Thomas Ellen was our fourth-grade nun. She was probably not yet thirty and not bad looking (even covered head to toe in the traditional religious habit), in my opinion, as a mature eight-year-old.

One day, as our fourth-grade class was getting into outdoor play clothes in the basement locker area, I said to Eugene Willis, “Sister Thomas Ellen gets to watch us boys take our pants off every day. I would like to see her take her pants off just once.”

Well, Willis immediately ran up to Sister, and I saw him whisper something in her ear. I presumed it was verbatim what I had just said, but nothing happened until later. After play period, Sister came up to me and said, “What did you say earlier?”

I said, “I can’t tell you.”

So we went to the refectory, and again after supper, she continued, “What did you say earlier?”

I said again, “I can’t tell you, Sister,” getting a little worried now.

As study hall was ending, Sister Thomas Ellen came to my desk, tapped me on the shoulder, and said for the third time, “Tell me what you said earlier,” and she added, “If you don’t, you will have to go see Sister Hermann Joseph, the mother superior.”

Well, I knew what that meant, probably expulsion and a trip back to Roscommon on the next train. So I figured she already knew what I said and just wanted me to repeat it. So I started to cry and through my tears told her exactly what I said expecting the worst. I said, “Sister, I told Eugene Willis that you get to watch us take our pants off every day, and I would like to see you take yours off just once.”

She stood up straight (she had been leaning over my shoulder) and said, “Okay then.”

Nothing more was ever said about it, either that night nor that school year, nor the next four and one half more years at HDC. My guess is that at the evening gathering of the nuns, Sister probably told the other nuns, “You’ll never believe just what one of my students said.”

In the fifth grade I started playing the tenor saxophone and was good enough to play in the school marching band. Our band was invited to play in Briggs Stadium (later called Tiger Stadium). We also played in the Marion year parade in Windsor, Ontario, in 1954. I have included a picture of myself playing the tenor sax, which appeared in the parade section of the Detroit Free Press. Tony played the trombone and traveled to the same events.

We didn’t see each other every day, at least not to talk. His class of about forty to forty-five students were moving through the halls of the Hall independent of my class. We marched everywhere in two files. We would bump into each other for band practice, later for football practice and games. We also both played on the school team. Of course, when it was time for vacations back up north in Roscommon, we would either take the taxi together or our military drill instructor, Lieutenant Hyland, might drive us to the Monroe Depot. We both seemed to like our independence. I wasn’t leaning on Tony, and he didn’t feel like the needed big brother.

A typical day at the Hall of the Divine Child was to be up at 7:00 a.m., awakened by reveille, always reveille. Head to the bathroom and sink areas. Each class had its own sink area with probably forty sinks. Every other day, it was to the chapel for mass; Fr. Stanley Bowers was our chaplain for all of my six years at HDC. He was an ex-boxer, either college, military, or pro, I never found out. We knew we didn’t want to be on the wrong side of Father Bowers. He was the ultimate disciplinarian. Much later, sometime in the mid-’60s through the eighties, Father Bowers was the pastor at a church in Dundee, Michigan, and became friends with my future wife’s cousin, Bob Miller, pastor for the local Lutheran church in the same town. Pastor Robert J. Miller wrote a book about his time as a missionary in Ethiopia, Tales of Tchinia: Two Families in Ethiopia.

One time when our seventh-grade class was in chapel for our biweekly mandatory confessions, the entire class (forty students) were on our knees examining our conscience in preparation for our turns in the confessional box with Father Bowers. We heard Father Bowers exclaim from the dark confessional box “You did what!” as he slammed the privacy door. Immediately all forty heads turned to the right to see who it was that could provoke such a response. Then Regelski came out and with head down, trying to look invisible as he made his way up the side aisle toward the front of the chapel where we’d normally say our penance. I’m sure we all saw who it was and prayed that our sins would not get the same response from Father Bowers.

There was a book, at least a manuscript written about Father Bowers and the Hall of the Divine Child by my classmate, Dennis McIntyre. I know that because Dennis let me read the manuscript when I met him, Mike Sweeney, and Paul Ewing at the University of Michigan in 1964. McIntyre won the prestigious Hopwood Award for Literature that year at the University of Michigan. Dennis later went to New York and had a very successful career as a playwright. Probably his most successful play was Split Second, which appeared in a theater just off-Broadway. I was in New York when it was playing, but I am sorry to say that I couldn’t get a ticket. National Anthems, Modigliani, Children in the Rain, and Established Price are other plays by Dennis McIntyre.

McIntyre died of stomach cancer in 1990, I spoke to him on the phone a few weeks before the end. Dennis told me that he had a new play for which Al Pacino was considering taking the lead role. McIntyre said to me, “If Pacino takes it, I could make a million dollars, but Terry I won’t live long enough to know.” Paul Ewing has his manuscript about the Hall of the Divine Child, entitled “The Divine Child,” and it remains unpublished to this day.

Following chapel, it was to the refectory for breakfast. We always had plenty to eat and usually a good choice. Then it was morning classes, lunch, and afternoon classes followed by probably two hours of free outdoor recreation. We could play any type of ball. I usually played whatever was in season. It seemed that most of the students played ball. We would have baseball, soccer, and basketball, and even handball courts were available. I didn’t play much handball. In the spring it was marbles and kites. I was definitely the “king” of marbles in my seventh- and eighth-grade years. Some students and I were few of those who would be a merchant or vendor. Here’s the deal: The vendors would make a hole in the ground, say six to ten inches deep and wide, then place a boulder or several “desirable” marbles in front of the hole, just close enough to the hole, so that when the players (the richer kids whose parents could buy them lots of shooter marbles) started throwing their marbles at my prize marbles from behind a line in the sand, they would win the big marble when they knocked it in the hole. The vendor (myself) got to keep all the marbles being thrown. Sometimes you’d have three or four boys firing their marbles at the same time. You could win lots of marbles. I still have many of my winnings some sixty years later.

My little brother, Louie, played with my winnings with our Leonard cousins back on the farm in Roscommon. Naturally, some marbles were lost. I found some in the chicken yard. Louie, who was born in 1951, was not sent to the boarding school. He was conceived on the recommendation of my grandma Cherven. I heard my mom complaining to her about Tony and me being sent to Monroe. I heard my grandmom tell my mom, “Well, just make another baby!”

I think I was present at my little brother’s conception. It happened one night when I decided to scare my parents by holding up my glow in the dark coonskin cap from under their bed. Our parents had gotten Tony and I both Daniel Boon–style coonskin caps for Christmas in 1950, the ones with glow in the dark eyes in the front. If you held them near a lightbulb for a while, the glowing would become quite bright and last for twenty to thirty minutes. So after charging up my cap, I crawled from my bedroom to Mom and Dad’s room, hiding under their bed, waiting for them to come upstairs. Well, I didn’t wait long before they were in bed, and I could tell by the commotion that Dad was getting frisky. I didn’t expect anything like that, but I had invested considerable time getting ready to scare them with the glowing eyes, so I made my move before I thought the old swayed bed would come down on me.

When I raised the coonskin cap up over the side of the bed, right over as it turned out, my mom’s head, my mom shrieked, “Bernie, I’m seeing stars!”

My dad said, thinking he was doing a good job, “That’s all right, Pauline.’’

She continued, “No, I really am seeing stars.”

I figured my job was done and quickly crawled back to my room before being discovered. I never had the courage to ask either Mom or Dad about that night. Louie was born on October 14, 1951.

Back to the schedule, following the recreation period, it was time to clean up for dinner (supper in those days). I learned that farm people like me had dinner and supper and city people had lunch and dinner. Then another ninety minutes of study before taps, and the cycle started again. Saturdays and Sundays were different. Most of Saturday was free recreation time. In winter we could ice skate at the pond. There was always a hockey game going on at the far end. James Benso was the best goalie. He had all the equipment, and Paul Ewing was the best center. He could score at will, stick-handling the puck all the way down the ice. I am sure the great Wayne Gretzky was no better than Ewing at thirteen to fourteen years old.

When I was in third grade, I must have been cute because one of my classmates’ sister from St. Mary’s, the adjacent girls’ academy, chased me down on the ice, knocked me down, jumped on top of me and proceeded to kiss me repeatedly while our third-grade nun stood nearby, watching with a smile on her face. I was helpless because my classmates held me down for the duration. The girl, maybe it was Linda Wells, broke a serious rule on the pond: boys on one side and girls on the other and rarely was that rule ever broken. The nuns usually strictly enforced it.

Sundays were always special days. For one thing, we had a full-length current movie every Sunday evening. One movie I do remember was The Long Gray Line about a boy in military school who got into trouble for contacting a girl at the nearby girls’ academy, reported on himself, and was expelled. After seeing the movie, my good friend, Eugene Willis, reported on himself for doing the exact same thing and was expelled from the Hall just before eighth-grade graduation. There is a picture of me and Willis in our football uniform in this chapter.

Also, in late morning, it was a full military review in our dress uniforms. There was usually a white-glove inspection of our lockers by the military commandant. He would usually reach into the highest shelf, running his gloved finger across the full length of the shelf. Any sign of dust would be serious demerits, maybe enough to cause a student to lose movie privileges that night. After inspections and full-dress review came visiting hours from 1:00 p.m. to usually 6:00 p.m.

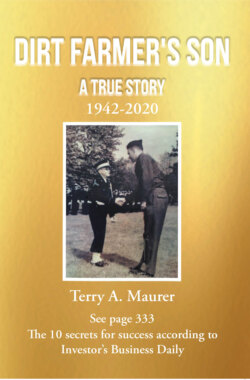

My parents came to visit Tony and me just once per year; that was on Mother’s Day. Mother’s Day came on the second Sunday in May and was the school’s biggest day of the year, the military review (like the annual tattoo in Edinburgh). Every class, first through the eighth participated in full dress review and marching competition. It took two to three hours of marching and standing at attention before it was over. It was the day for the entire school to show off what we learned about marching. The band was front and center as well as the special drill team with maneuvers with fake rifles. It was in 1954 on Mother’s Day that I was recognized as honor corporal for the entire school. I was chosen as the best corporal out of more than thirty corporals schoolwide. That is the picture of me receiving the medal from Lieutenant Hyland, the commandant, on the cover of this book.

Since Mother’s Day was the only time my parents came to visit and there was visiting every Sunday, that is if the students’ parents could get to Monroe. Most students were from a reasonable driving distance; that’s from Detroit, Toledo, and other towns within sixty to seventy miles of Monroe. Paul Hebert and Tim Gillett were from Mt. Clemens. Michael Day was from Cleveland, Mike Sweeney, and the Saab twins, Arthur and Allen, were from Toledo. Most of the students were from wealthy families. The wealthiest in my class was Everett Fisher from Detroit. His father was one of the “Fisher body” brothers, and his mom was part of the Briggs family. His mom’s family-owned Briggs Stadium, later to be called Tiger Stadium. My classmates would invite me to join them and their family for dinner or some other outing nearly every Sunday. The Fishers would come in their Flying Dutchman, a first-class motor coach, the size of a Greyhound bus. It was always a memorable day when I’d get to ride around Monroe in the Flying Dutchman.

One of the most accomplished graduates from the Hall of the Divine Child who I met in the ’80s was Jay Wetzel. Mr. Wetzel was a 1950 graduate who was picked by General Motors’ chairman, Roger Smith, to be the first Saturn employee. Jay told me he was allowed to select any seven leaders from sales, manufacturing, finance, marketing, research within GM, to assist him setting up the new Saturn car company in Tennessee.

As it happened, fresh out of Bowling Green University in 1991, my son, Stephen, was one of the first Saturn sales associates for Saturn of Plymouth. Jay Wetzel’s Saturn car sold very well. Steve frequently was the lead salesperson, corporate-wide, even outselling Mary Wetzel (Jay’s daughter), who was at a different Michigan dealership.

Perhaps the most popular students at HDC during my time were the Schoenith twins, Tom and Jerry. Their father, Joe, owned the Gail Electric Company, which sponsored the Gail hydroplane racing boats on the Detroit River. Later, their Roostertail Restaurant was a very popular spot for the Motown crowd, including the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, and Marvin Gaye.

In the summertime, some of these HDC families would visit our family farm in Roscommon some two hundred miles north of Monroe. My dad always enjoyed showing these rich city folks our flowing wells. One of the parents told my dad in 1955 that the artesian water tasted so good that he should bottle it and sell it to the folks in Detroit. My dad would laugh and go back to the barn and shovel some more manure, knowing that what he was doing was far more important than listening to the crazy city people. It would be another thirty years before Terry Maurer (me) would put the first of this most remarkable artesian water in a glass bottle and offer it for sale as deMaurier and later Avita.

In seventh grade, we were considered upperclassmen and could play on the varsity sports teams, if we were good enough to make the team. My brother and I both played varsity football. However, my most memorable year on the team was in eighth grade when HDC went undefeated again. Our 1955–1956 team was led by Paul Ewing as quarterback. I was first string left half back. I scored three touchdowns in one game against the weakest team in our CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) league, St. Michael’s from Monroe. Even so I remember that Joe Turowski called me the hero of the game. Joe’s gorgeous older sister had a date with Kirk Douglas on a vacation to Los Angeles in 1955. I don’t remember the final score.

In another game that year against our toughest rival, Trenton, I made a game-saving tackle on defense. Here’s what happened: we kicked off late in the game, and the biggest guy on Trenton’s team received the ball and was speeding through all our defenders. There were two “deep” defenders, me at 4'10" and either 5'8" Gordon Rebresh or Willis between their goal line and a game-winning touchdown. I could see the Trenton fullback turn toward my side of the field at full speed. I knew our coaches, and everybody on the sideline was watching the action. There was no way that I could fake a tackle and lose the game, so I decided not to wait for the Trenton full-back to reach me. I ran full speed directly at him and left my feet and hit him like a torpedo in the midsection. He went down like a sack of potatoes. He couldn’t believe that the little defender did not chicken out. Well, when I got to the sidelines, our coach was bragging to his assistant about the great tackle which Tom Kulick just made. Tom Kulick is just about my size, but it was my tackle, not Kulick’s. Only my friends knew I saved the game, and I never told the coach it was me.

As an adult, Paul Ewing could play the piano like a concert pianist, and he was a very successful businessman in Detroit, manufacturing automotive and heavy equipment fasteners at his NSS Company. His wife, Mary Sue, sang for the Detroit Opera. They both entertained us at our home, Paul playing and Mary Sue singing. The music was remarkable.

Also, a turning point in my future education was developing for me during seventh grade. Ironically it involved a girl, Linda Wells, from St. Mary’s Academy who saw me serving mass at the IHM Convent on Sunday and for all of the Academy girls, all four hundred of them at their chapel. As it happened Linda decided to send me a bracelet with both my and her name engraved on it. Now, it is true we never spoke to each other either before or after the gift. It was all about eye contact as I held the paten under her chin when I was the altar boy for Monsignor Marron at the girls’ mass. The bracelet arrived in my hand through one of my classmates who had a sister in Linda’s class at the Academy.

It was probably the next week that the new Mother Ursula, head nun, pulled me out of my seventh-grade religion class into the hallway, grabbing my wrist and my bracelet. She said, “You are being expelled from school for making contact with a girl from the Academy. The commandant will take you to the train depot this afternoon.” I was shocked! She also said, “The girl has already been sent back to Ann Arbor, expelled, gone for the breaking this unholy rule about no contact between the boys and the girls.” The new mother superior was making a statement, letting everyone know how tough she was. Much like Bowie Kuhn, commissioner of baseball, suspending Denny McClain in 1969. Go after the popular kid, and then everyone will fear you. It happens all over the animal kingdom.

Mother Ursula had to inform my brother that I was being sent home. The mother superior told me it would be later in the day before I would be taken to the depot. During that time, my brother Tony was able to convince this new disciplinarian that I should not be kicked out. What happened instead was a formal military court-martial. I got busted. Tony was on the battalion staff as a first lieutenant. The battalion staff was like the joint chiefs of staff in the real military, a big deal. So on the scheduled day, I appeared in front of this four-member group. A fellow named Valmassi was the chief of staff with my brother and two others. I remember Valmassi reading something about the bracelet from Linda Wells. I said something like “I didn’t ask for it” and “never really met the girl.” No luck, they told me that I broke the rule and my rank would go back to buck private. At least I was not kicked out of school. So although I was not happy that my own brother voted against me, it obviously was the best compromise and did stop the immediate expulsion. At Thanksgiving vacation that year, our friend Floyd Millikin gave Tony the raspberries for busting his own brother. That same day, my friend Paul Ewing also got court-martialed, and I learned later directly from Paul that it also had to do with a girl from the Academy who lived in Monroe.

My days and years at the Hall of the Divine Child Catholic Military School in Monroe, Michigan, were happy days. I had many good friends and got a good elementary education. The opportunity to play all the sports, learn to swim, and have picnics in the big woods and the little woods. I did not mind all the marching and day uniforms and Sunday dress uniforms. We were always told to wear our dress uniforms when we went to mass on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter vacations in our hometowns. Maybe the uniform code was to advertise the school or so that we would not forget how to behave. The uniform has a way of improving one’s behavior. My parents always, I am sure, were proud to show us off. Well, you can’t blame them for that because we were only home for a short time during the nine months of the school calendar. It seemed we were forever catching the train, coming or going between Roscommon and Monroe.

Last-minute projects sometimes made us late for the midnight train out of Roscommon. On one particular vacation night, the steam engine was already about to pull out of our little village, population of 750 in 1955, when we arrived in a big hurry in Dad’s old red GMC pickup. All five of us, Dad, Mom holding Louie, Tony, and I were in the one-seater. As we crossed the tracks in front of the train on Main Street, Dad said, “I think the train is starting to leave the station, you’re going to miss the train unless I stop right here on the tracks.”

Mom said, “You can’t stop on the tracks!”

Dad stopped in the middle of the tracks anyway while the glaring light on the locomotive lit up the pickup. All the while, the steam engine’s whistle was warning us to move off the tracks. Mom said, “What are you doing?”

Dad answered, “The train won’t leave as long as the pickup is on the tracks. Boys, grab your suitcases and run with me to the depot!”

It was about forty yards away. That’s what we did, hollering, all the time, our goodbyes to Mom and Louie, who we presumed would not stay in the truck.

Grandma Cherven, Terry, and Pauline at HDC.

When we finally got to the station, the train was nearly full of passengers. Tony, Pat Jansen’s brother Charlie, and I finally boarded the midnight express. Pat Jansen was later to be Tony’s first girlfriend when he finished eighth grade at the military school and started his freshman year at Grayling High School in 1956. That same year Elvis Presley made a hit with “Heartbreak Hotel.” So Tony told me to take a seat by myself at the end of the first passenger car, and he would sit with the new kid, Jansen, in one of the first seats.

Terry Maurer, front row, second from right.

We were all showered and dressed up in our Sunday uniforms, looking like little soldiers. The shower was necessary because we had just finished helping Mom and Dad cut the heads off thirty to forty chickens and pluck all the feathers. Dad always had last-minute projects for Tony and me so as to get the final free labor out of us before returning to school. Now, back to finding my seat on the train, I proceeded to walk the length of the railroad car by myself, when coming to the end, I bumped into a very attractive young lady, probably eighteen to nineteen years old, talking to three or four of the train conductors who had time and were eager to visit with the young lady as the train was late departing (there was a truck on the track). Ignoring them, except for the enticing perfume, I squeezed by and took my seat alone. Now, I went to sleep almost immediately but woke up when we stopped in West Branch to pick up more passengers and more than likely drop off the cream cans for processing into butter at the local creamery. I thought I was in heaven, twelve-year-old heaven, because I found myself in the fragrant arms of the beautiful nineteen-year-old whom I had noticed as I took my seat.

I said to her, as we were face to face, that was the position I found myself, through no fault of my own, “How did you get into my seat?”

She answered in a low soft voice, “Well, when the train stopped in St. Helen, two nuns got on board, and they wanted to sit together, so I gave them my seat and came back to sit with you.”

I said, “I’m thirsty.”

The mirage beauty said, “I’ll get you a drink.”

So she got up, walked to the front of the train, got a paper cup of artesian water (at least it tasted like artesian water on that night), and brought it back to me. I asked her where she was going. She told me that she was a sophomore at Mary Grove College in Detroit and was returning back to school like me after the Christmas break.

She said, “Why don’t we get back into our position?”

I never wanted to go to sleep, but I did. And I didn’t want the train ride to end. But it did. Obviously, one remembers a train ride like that. I do remember the first popular song, which I really liked: It was “Why Do Fools Fall in Love?” by Frankie Lyman.

Toward the end of my eighth-grade year at HDC, I began to think of my future. Most of my classmates were talking about where they would go to high school, places like Marmion, the military high school where Eugene Willis actually did go and did exceedingly well, Divine Child in Detroit, Assumption in Windsor, Canada, and of course Cooley and Denby. I am not sure when I thought about Holy Trinity for myself, but I do remember a missionary priest with a dramatic priestly habit, a wide cincture holding a large crucifix on the side, visiting our school in 1954, two years before my graduation. So I asked Father Bowers if he remembered the visit from the missionary priest from Alabama. He did and put me in touch with the religious order headquartered in Silver Springs, Maryland. It wasn’t long before I got a visit from Father Doherty, the vocation director for the order. I was accepted to the minor seminary in Alabama and would start as a freshman in the 1956 class in the fall.

The summer of 1956, before beginning seminary in Alabama, is when I saved someone from drowning for the second time. This time it was my best friend Floyd Millikin, who we all knew could not swim. Floyd’s neighbors, or rather his parents’, Roy and Virginia’s, neighbors, owned this little gas station with attached coffee and sandwich shop. A very common arrangement throughout Northern Michigan, and I believe throughout the country before the interstate highway system replaced those family businesses with McDonald’s, Burger King, and others along the expressways. It was I-75 that changed our part of the country and not for the better, according to my dad. Well, the fellow who owned the station had a cute, thirteen-old-year daughter named Holly who lived down Fletcher Road. Holly had a friend named Bridgette. Both girls would go waterskiing while their dad piloted his speed boat on Higgins Lake.

On this particular summer day, the girls invited Floyd, Tony, and me to go skiing with them. Off we went, putting in near the B&B Marina on Higgins Lake’s North Shore. Tony skied first, then I skied; all the while the two girls watched from the safety of the boat. Finally, Mr. Potts asked Floyd if he wanted to give it a try. I remember the last thing Floyd’s mom, Virginia, said as we left her doorway, “Remember, Floyd can’t swim, so he can’t ski.” Well, Floyd said he’d like a turn on the skis, and he did quite well getting up on the first attempt.

Now, I’m in the boat telling Mr. Potts, “Floyd can’t swim, so just go straight so that he won’t fall on the turn.” He went straight all right, straight out into the dark-blue water and past the drop-off. When I noticed the color of the water, I said to Mr. Potts, “Holy cow, you better get back to shallow water, but make a slow turn, because Floyd might fall, and he can’t swim and he doesn’t have a life jacket.” Just as soon as the turn started, Floyd fell off into Higgins Lake, past the drop-off where the water was easily one hundred feet deep.

Floyd and Tony in 1958.

Knowing Floyd couldn’t swim, I immediately jumped off the boat, swimming toward Floyd as fast as I could. He was kicking himself back to the surface for the second or third time when I got to him. Immediately he grabbed on to me like I was a sturdy red pine. Down we both went with Floyd grabbing my arms, making it impossible for me to swim or help keep Floyd’s head above water. Finally, I was ready to punch him in the mouth, hoping I’d knock him out (I heard once that this should be done). Then I heard Tony howling from the shallow waters to the screaming girls, “Throw them some seat cushions!” Mr. Potts had stalled his boat at least thirty yards from Floyd and me. He was pulling the starting rope repeatedly with no luck. It was the cushions and me dragging and talking to Floyd, “Hang on, hold on, we’re almost to the boat” that kept him from going down for good. I am sure Floyd coughed up at least two liters of Higgins Lake. I think he learned to swim when he became a Michigan state trooper.

Hall of the Divine Child, Catholic Military boarding school.

The last graduating class of Holy Trinity, Alabama 1960. Back row: left to right, Carl Seeba, David Lopata, Wayne Putnam, Bruce Cummings, Rich Schoessow, Marty Hendricson. Front row: Pete Krebs, Clif Marquis, Roland Haag, Terry Maurer, Roger Skitton.