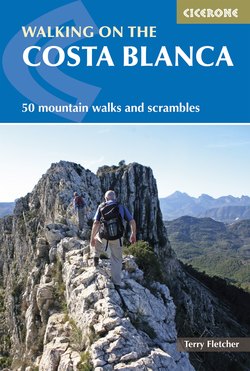

Читать книгу Walking on the Costa Blanca - Terry Fletcher - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The 'sleeping lion' of the Ponoig as seen from near Polop

Think Costa Blanca and, as likely as not, you’ll think Benidorm and lager louts. Well get ready to think again.

It’s true that this was one of the first areas discovered by tourists during the package holiday boom of the 1960s and 70s, helping to make Benidorm Europe’s biggest holiday resort, but in recent years those who came in search of sun and sangria have been joined by a new kind of visitor not content to pack the bars and clubs into the small hours and sleep it off on the beach next day. First it was climbers who discovered the ‘sun rock’ potential of the inland crags and coast but in recent years they have been joined by growing numbers of walkers and cyclists so that today rucksacks and bike bags increasingly jostle with the matching Samsonite and fake Louis Vuitton on the baggage carousels of Alicante.

The key lies in a climate that offers more than 300 days of sunshine a year. Summer temperatures may be stiflingly hot but for the rest of the year they are more amenable to exercise, akin to those of an English spring or summer.

And just beyond the beaches and high rises lies a completely different world of accessible, rocky mountains rising to 1500m – higher than Ben Nevis – and knife-edge ridges that stretch away in long chains of gleaming white limestone pinnacles like the bleached skeletons of dinosaurs’ spines. Of deep, dry barrancs – the local catchall that encompasses everything from wild canyons winding their way for kilometres on end between the mountains to narrow gullies etched deep into the slopes – where it is possible to walk all day and not see another soul. Of slopes clothed in pine-scented forests or olive and orange groves. Of valleys dusted with the delicate pink and white blossoms of almond trees growing on miles of terraces laboriously hacked from the hillsides centuries ago by desperate farmers but which are now often being slowly reclaimed by the mountains. Of narrow paths where your boots kick up the fragrance of wild herbs leading to still-used fonts, springs and wells that made life in this arid landscape possible. And all set against the backdrop of the glittering blue Mediterranean which adds a beguiling extra dimension to any day out.

Looking from Monte Ponoig to Castellets Ridge (Walk 39)

The embryonic footpath network is often based on centuries-old trading routes dating back to the long occupation of Spain by the North African Moors, their old cobbles and steps still clear beneath your boots. Nowhere are these old ways more remarkable than on the aptly-named 10,000 Steps (Walk 22), which penetrates the formidable depths of the imposing Barranc del Infierno (Hell’s Gorge). Others climb to the ruins of castles and watchtowers perched improbably on rocky spires, another legacy of the religious and ethnic wars. Today the old trails are being supplemented by more modern paths as the local authorities begin to cater for a new type of visitor. Simultaneously active walking groups, notably the Costa Blanca Mountain Walkers made up largely of British ex-pats, are reclaiming lost trails and in some cases, quite literally, carving new ones through choking undergrowth to lost valleys and inaccessible summits. The result is an initially strange but ultimately bewitching mix of wild mountain walking cheek by jowl with modern development, especially near the coast, and all within a couple of hours’ flying time from shivering Britain. Small wonder that the serras of the Costa Blanca have become a favourite winter adventure destination for sun-starved Brits and other northern Europeans, many returning year after year under the spell of these magical mountains.

The path leading to the col between the North and South Ridges of the Ferrer (Walk 14)

Geology

Even the most cursory glance will reveal that these mountains are made of limestone, creating a type of landscape that geologists and geographers call karst. It is a porous and soluble rock which explains the almost complete absence of running surface water or lakes and conversely the almost universal presence of dry ravines and gorges worn out of the underlying bedrock over millions of years.

The rock was formed 200 million years ago from the compressed remains of countless sea creatures that fell to the ocean floor. The rock moved northwards on shifting continent-sized tectonic plates and when plates collided huge areas of rock were thrust upwards, creating ridges and mountain chains with much of the present landscape shaped within the last five million years.

The Costa Blanca lies at the northern extremity of the Betic Cordilleras that stretch from Andalucía in southern Spain in an arc culminating in the islands of Ibiza and Majorca and contains sizeable areas of limestone pavement with blocky clints divided by grykes. Where the pavement is clear it can make for easy walking, as on the Alt de la Penya de Sella (Walk 36), but where the ground is covered by vegetation it becomes treacherous, providing a strong incentive to stick to the paths.

Below ground the landscape is equally dramatic with water creating underground passages and channels. More than 6000 caves have been recorded with exploration revealing more all the time. Show caverns, such as the Coves del Canelobre, passed on Walk 47, offer the non-caver a glimpse of what lies beneath.

Wildlife

If there is a single major disappointment to walking on the Costa Blanca it is the distinct shortage of wildlife or at least visible wildlife. Many blame this on the Spanish passion for hunting and there may well be truth in that, although whether that is because the creatures have been annihilated or merely become sensibly wary of humans is debatable. In any event the creatures you are most likely to see are wild goats and birds. Boar are relatively common but are mostly noticeable by the dug over earth they leave in their wake. They are not normally dangerous and, unless cornered or protecting young, will usually beat a swift retreat. Wild lynx, polecats and foxes are similarly shy – with the notable exception of a fox that turns up at the bar in Famorca in search of titbits. Red squirrels, now rare in the UK, may also be seen.

Famorca's bar-crawling fox (Walk 44)

There are also several species of snakes, although you are more likely to see them flattened on the road than meet them in the undergrowth. Only the vipers, identifiable by zigzag markings and triangular heads, are dangerous and even their bite is rarely fatal, but should be treated swiftly. Statistically bee stings kill more people. More unpleasant too is an apparently humble caterpillar. The pine processionary moth takes its name from the way its caterpillars, once they leave the silky nest they spin in pine trees, move nose to tail in lines which can be two to three metres long. Do not be tempted to touch them. The hairs are extremely irritating and can cause serious allergic reactions. If one should drop on you do not brush it off with your bare hands. It is said the only solution if you get the hairs on your clothing is to burn the garment!

Nest of the processionary moth... do not touch!

Birds are nowhere near as commonplace as they should be but with an estimated 70 per cent of European species either resident in Spain or passing through as migrants there are some spectacular sights to be seen. Most colourful are the hoopoe, the golden oriel and the bee-eater, while birds of prey will occasionally be spotted, including griffon vultures around the Barranc del Cint (Walk 49), eagles and peregrine. Choughs are also common in the mountains. The coastline possesses a wealth of seabirds while just inland the salt lake of Calp is home to flamingos, egret and cormorants. The rice marches north of Denia are popular with birdwatchers, as is the Albufera Natural Park south of Valencia.

Plants and flowers

The area’s gentle climate means there are flowers virtually all year round but February and March are generally acknowledged as providing the finest displays. Although hardly wild, the almond groves are explosions of pink and white blossom while beneath the trees are carpets of daisies. It may seem odd to get excited over a lawn weed but the sheer number of flowers makes the showing spectacular. The profusion of wild orchids can be particularly striking. With more than 3000 plant species identified in Alicante Province it is impossible to name them all, but many are dwarf varieties. Dedicated botanists will be kept happy for hours while the general walker can simply enjoy the uplifting effects of the mid-winter displays of colour as rising paths climb through vertical zones from lush Mediterranean to Alpine.

Dwarf daffodil

History

The story of the Costa Blanca is etched into its landscape, the names of its villages and the faces of its inhabitants. The earliest evidence of Man is to be found in the cave paintings of Petracos, near Castell de Castells, passed on Walk 25, which are thought to date back more than 5000 years. Later came Phoenician and Greek traders to be followed by the warring armies of Rome and Carthage as they fought to control the Iberian Peninsula. The Carthaginians founded Alicante but ultimately were no match for Rome.

However, the most significant invasion was by the Moors from North Africa crossing the Straits of Gibraltar in 711. Within five years they had reached Alicante and began a rule that lasted 600 years. During that time Christians were tolerated and allowed to practise their religion. These Mozarabs were largely responsible for creating a remarkable network of trading routes across the mountains. They were so well-engineered that many still exist today and form some of the most popular walks, notably the 10,000 Steps (Walk 22). The Moors, with their knowledge of irrigation and water handling, were also instrumental in establishing for the network of wells and fonts still in use today.

Mozarabic trail 10,000 Steps (Walk 22)

A much more visible legacy of centuries of war is the huge number of castells, which sometimes seem to crown almost every hilltop. In truth most are little more than watchtowers but exploring these mountains you will find no shortage of Penyas del Castellet. Since the name means Castle Hill this is hardly surprising since, if there are two things here in abundance, they are castles and hills.

Fort de Bernia (Walk 10)

After centuries of Moorish rule came the Reconquista (Reconquest) in the 12th century when Alicante was again brought under Christian rule. Some Moors, who converted to Christianity, were allowed to remain and it was not until 1609 that they were finally expelled from the region, though coastal raids by Berber pirates continued long after. The events are still celebrated in lavish annual festivals of Moors and Christians, mostly between August and October, re-enacting the great battles and the taking of each town.

The Arab influence still remains, not least in the names of many towns and villages. Most common is the prefix Beni, meaning ‘sons of’ and usually refers to a tribe or clan. Other names beginning Al are also often Moorish in origin. Their other lasting imprint is in the huge number of agricultural terraces climbing high in the hills and sometimes to the very summits. Many date from the time of Moorish rule but others from a later population explosion, which demanded more ground be brought into production.

Getting there

Thanks to its long-established tourism infrastructure, the Costa Blanca is perhaps the most accessible of winter destinations with regular, often daily, flights from most major UK and northern European airports to Alicante, the main gateway to the Costa Blanca. Murcia to the south entails a slightly longer drive.

Those who want to take their own vehicles face either a long drive across France or a ferry to Santander or Bilbao. The A7 motorway runs just inland from the coast but tolls can be expensive. Even the relatively short 60km stretch from Alicante to Calp costs more than €5 (2015).

Trains and buses run up the coast from Alicante to the major resorts.

Getting around

The inland villages of the Costa Blanca are not blessed with the most comprehensive public transport system and, with the exception of a bus service option for Walk 27, readers will be reliant on cars at the start and finish of each day. With this in mind, almost all of the walks have been devised as circular. Car hire is relatively cheap, sometimes as little as £30 or £40 a week in winter, and is best arranged before arriving in Spain. Most major international hire companies as well as numerous local ones have bases at Alicante airport. Be aware, however, that although most offer unlimited mileage some restrict users to 2000km per car, after which the vehicle must be exchanged. Exceeding the limit can result in punitive charges of €2 a kilometre. New UK rules on paperless driving licences also came into force in summer 2015 (see www.gov.uk/news/driving-licence-changes).

The alternative to car hire is to stay in one of the mountain villages that offer local walking or where property owners are prepared to offer a taxi service, as many will.

See Appendix C for more public transport details.

When to go

The length of the walking season depends on your tolerance to heat but in general late autumn to early spring is most likely to suit UK and Northern European visitors. Even the locals avoid the summer heat. September and October boast average temperatures still in the high 20s but may also be affected by the gota fria, a cold wind that also brings spells of rain, while December and January can provide short-lived snow, especially in the highest mountains. But generally the months from November to early April have temperatures in the high teens while still bringing an average of six or seven hours of sunshine a day. Rainfall is highest in November.

February has the added attraction of the spectacular display of almond blossom while March to May brings out the finest display of wildflowers.

Almond blossom and the Serra Bernia (Walks 10–12)

Where to stay

Accommodation is plentiful on the coast, especially in Benidorm, which has more beds that any other European resort, and countless companies offer package deals. However its boisterous ‘charms’ are not for everyone. Altea and Albir a little further up the coast are more sedate. Calp is a popular base for walkers. It has apartments and hotels aplenty and no shortage of restaurants and bars while still retaining a very Spanish atmosphere.

Those who prefer to stay among the mountains will find increasing numbers of casas rurales, self-catering villas as well as B&Bs, hotels and hostels, many catering for walkers and some offering guided walking or at least the prospect of transport to and from the hills. Popular villages include the very pretty Guadalest; Sella and Finestrat, which are convenient for Walks 36 and 37 and those around the Puig Campana; and Castell de Castells, which can be a handy base for exploring the Serrella and Aixorta (Walks 31–32 and 43–46). The string of towns and villages of the Vall de Pop (still better known to many Brits as the Jalon Valley) such as Xalo, which is well-served with bars and restaurants, and the smaller Alcalali are well placed for exploring Walks 10–18. At the top of the neighbouring Vall de Laguar are the quiet villages of Fleix and Benimaurell, which overlook the cleft of the Barranc del Infierno but are less well served either for eating or entertainment. Typing ‘Costa Blanca accommodation rentals’ into any search engine will bring up a wealth of choices. Those lucky enough to be able to take extended breaks can often negotiate cheaper rates.

For those on a tight budget or who prefer to be right in the heart of the mountains there are basic climbers’ refuges, notably at Sella, Guadalest and Pego.

Market in Sella

What to take

Clothing

On some of the more popular mountains you may meet people wearing light trainers and even sandals but comfortable walking boots with solid soles and plenty of tread are strongly recommended. Not only will they provide ankle support and give a better grip on eroded paths they will also protect feet from the battering dished out by hours of walking on sharp limestone.

Sun-worshippers may be tempted to pull on their shorts at the first glimpse of the Costa Blanca’s blue skies but before you do so remember the vegetation here is typically Mediterranean. It often consists of thorn bushes or shrubs with sharp, spiky leaves that will mean that after a week or two of walking your shredded legs may have little left to show of that hard-won suntan. If you are determined to wear shorts pack the zip-off variety that will at least give the option of covering up if the undergrowth becomes too painful.

Sun hats are essential at almost any time of the year but so too is warm clothing. Temperatures in winter at high altitude can be chilly and winds strong. A sunny morning on the coast is no guarantee of similar temperatures in the mountains.

Wild March day on Montgo (Walk 1)

Equipment

The normal mountain gear of spare food, clothing and windproofs, plus, in winter, waterproofs as well as map, compass and a torch should be carried. Even if you do not normally use trekking poles they are worth considering. Not only will they provide a couple of extra points of contact on steep and loose paths they also come in handy for fending off the aggressive vegetation and even the occasional farm dog. The latter also usually respond to bending down as if picking up a stone. Or even to genuinely picking up a stone for that matter.

Water

Water is often at a premium in this arid landscape and walkers should make sure they have plenty with them. Even in winter at least a litre per person is recommended and in summer much more may be needed. Old wells and springs that dot the mountains are well preserved and often clearly marked on signposts and maps. However, although they are often still used by locals and even townsfolk who come to fill copious numbers of bottles from them, most fonts take their supply straight from the mountain. It is impossible for the casual visitor to verify their purity so without a lifetime’s immunity it may be safer to carry your own supply. That said, I have from time to time made use of the springs to top up water bottles and not come to harm – yet.

Font del Moli (Walk 35)

Safety and insurance

Through necessity many of these walks have been done alone and I have occasionally been taken to task by Spanish walkers for this. It’s hard to argue with them. Despite the intensive development along the coast these are lonely mountains and on many walks I did not see another person all day. On some an injured solo walker might not be discovered for days and mobile telephone cover is patchy, especially in the barrancs, so a companion is always a wise precaution.

Unlike the UK, there is no volunteer mountain rescue service and the regional government has warned that those who have to be rescued ‘through negligence’ will have to pay the cost of the rescue. If a helicopter is needed that could amount to thousands of euros, so visitors should be certain their holiday insurance covers them for all their planned activities and, if necessary, take out the specialist cover through organisations such as the British Mountaineering Council or the various specialist providers. See Appendix C for details.

Paths

These walks are chosen to give a taste of everything the area has to offer, from deep ravines to high ridges and picturesque villages to rocky summits. Many make use of the constantly improving PR-CV (sometimes abbreviated to PR-V) network of Pequenos Recorridos de la Communidad Valenciana. The name means ‘short walks’ although some can be more than 50km long. They are ‘short’ only to differentiate them from the long-distance GR network. Some of the most enjoyable paths are old Mozarabic trails (see History).

The need for circular routes has meant leaving out some excellent linear expeditions only available to those with access to two cars or a driver willing to drop them off and collect them at the start and finish. That would open up a whole new range of possibilities, notably full traverses of the various serras. Many of the PR-CVs are based on old trading routes between towns and villages and can only be fully explored by those with these flexible transport arrangements.

The paths and tracks used vary from rural and forestry roads to narrow trods that are little more than goat trails across steep slopes. The status of a path as a PR-CV should not be taken as meaning it will be either clear or maintained. Paths generally receive little attention and can be badly eroded and loose. A useful approach is to prepare for hard pounding and to welcome the easy sections or forest trails carpeted with pine needles as a welcome bonus. Because of the aggressive undergrowth, often hiding fissures in the limestone, any path is usually safer and infinitely preferable to bushwhacking.

Despite their proximity to the holiday beaches these are serious mountains with all the hazards that entails and are neither to be underestimated nor taken lightly.

Waymarking

The only consistent characteristic of the waymarking is the infinite variety of ways it finds to be ingeniously inconsistent. Even on paths of the same status, such as PR-CVs, it varies from excessively lavish to near invisible. PR-CVs are marked in yellow and white, occasionally on official signposts or, more frequently, with paint flashes on rocks, walls and trees. Two straight lines mean carry straight on, curved lines indicate a turning while crossed lines mean you are going the wrong way, probably having missed a junction.

From top: Markings showing a change of direction, straight on and wrong way

In addition some villages also have a network of local paths, senderos locals (SLs). Often little publicised beyond the village boundary, you may find them marked on a noticeboard in the village square or a local bar may have a leaflet. The more official ones are marked with green and white paint, mimicking the PR-CVs, while more impromptu tracks tend to have occasional splodges in whatever colour was to hand.

Signposting tends increasingly, but again not always, to be in the regional tongue Valenciano rather than Spanish and sometimes even switches between languages on the same walk. In the text, a pragmatic approach has been taken of using whichever name seemed, at the time of writing, to be most helpful given local signing.

As everywhere, signposts are at the mercy of vandals, souvenir hunters and grumpy landowners and can appear and disappear with alarming speed. Exploring an alternative finish to one route I discovered the most useful marker post had disappeared literally overnight.

Maps and language

It is said that a man with a watch always knows the time while a man with two watches is never quite sure. Those raised on the comforting certainties of the Ordnance Survey may come to feel much the same about Spanish maps. The only series to completely cover the area are the IGN ‘Military Maps’, which, to put it kindly, enjoy less than universal acclaim. In recent years they have been joined by various commercial competitors such as Terra Firma, El Tossal and Discovery. These are a vast improvement but as yet none covers the entire area.

Difficulties can also arise when trying to use different maps simultaneously, a problem compounded by the use of the competing languages, Spanish and Valenciano. The latter was suppressed during the rule of General Franco but is now making a strong comeback on road signs, waymarkers and, increasingly, on maps. The reintroduction is not being prosecuted with the aggressive vigour and even venom shown further north in Catalunya but the changeover is gathering pace. Road signs and waymarkers which were once in Spanish and later bilingual are more and more exclusively in Valenciano. Brits who have long had a love affair with the Jalon Valley now find only Xalo signed from the main road and Calpe is losing its final ‘e’. Benidorm remains forever Benidorm.

Mind your language... Spanish sign converted to Valenciano

This mix of languages throws up different spellings and occasionally even different names for the same places, which may bear little relation to each other. Readers are very strongly advised to carry the appropriate large scale map as well as the book. These can be bought from the larger suppliers in the UK and are available in Spain from shops such as the Libreria Europe in Calp, which also operates a mail order service. See Appendix C for details.

The main maps recommended are Serra Aitana, Serra Bernia, Montgo and Les Valls (Terra Firma), Costa Blanca Mountains (Discovery) and La Serrella and Serra Mariola (El Tossal).

A short Valenciano–Spanish–English glossary is given in Appendix B to help you follow maps and signs as you walk.

Using this guide

Information is given in a box at the start of each walk description, and also listed in the Route summary table in Appendix A, to help you choose the route that’s right for you.

Distances are given in kilometres and heights in metres. Because of the nature of the terrain and the quality of paths some of the walks demand a greater degree of mountaincraft and ability to navigate and move over difficult terrain than others. Please heed the warnings in the text and pick your routes accordingly.

Timings are as walked by me, a sexagenarian with high-mileage knees, and are inevitably subjective. They should be treated as a rough guide only until you have walked a few of the routes and had a chance to compare our respective paces. Please ensure adequate daylight to complete the walks until you have got the measure of my timings, which do not allow for stops.

Likewise the grade of difficulty is as I personally found it. Please take note of any warnings in the text. Easy routes are fairly gentle strolls. Moderate walks demand more effort and may involve rough going. Strenuous routes are demanding days, often with steep climbs and/or descents. The scrambles are about Grade 1 but may be exposed and broadly compare to routes such as Bristly Ridge or Crib Goch in Snowdonia or Sharp Edge in the Lake District. Some entail large drops.

The Serra Bernia (Walks 10–12)

A fast-changing region

All the routes were walked or re-walked especially for this publication. However, the Costa Blanca is an area in constant flux. Floods, fires and landslips can wreak dramatic changes within hours while at lower levels development continues apace. The financial crisis of 2008 stalled the building boom for a while before it regained momentum, fuelled in part by money from Eastern Europe. This means that some dirt roads are gradually being metalled or concreted, while new roads, or even entire developments, will appear over time.

If you come across a problem or a change please contact me via the publisher (see ‘Updates to this Guide’ in the prelim pages) so that alterations can be posted on the website and incorporated into future editions.

The abrupt headland of the Serra Gelada towers over the Benidorm high rises, from Calp