Читать книгу Great Mountain Days in the Pennines - Terry Marsh - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNORTH WEST DALES – EDEN VALLEY AND THE HOWGILLS

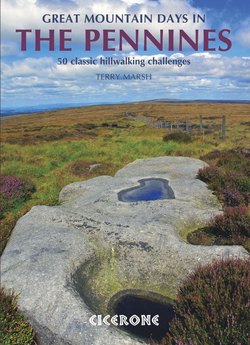

‘Watercut’ on the High Way above the Eden valley (Walk 11)

Possessing a geological affinity with the low fells around Windermere in Lakeland, and owning little of the moorland bog usually associated with the high summits of the Pennines, the Howgills are unique, a diversion from the main thrust of the north–south Pennines. Yet they lie just a short distance west of the Pennine watershed, with only the bulk of Baugh Fell to intervene.

Their name comes from a small hamlet in the Lune valley, which was supplanted by Ordnance Survey cartographers to give to a fairly well-defined group of hills a collective name; and quite fortuitously, too, for neither ‘the Sedbergh Fells’ nor ‘the Lune Hills’ has quite the same ring. ‘Howgill’ derives from two old Scandinavian words – one from Old Norse (haugr, meaning ‘hill’ or ‘mound’); the other from Old West Scandinavian (gil, meaning ‘ravine’). Combine the two meanings and it becomes easy to see why ‘fells’, as in ‘Howgill Fells’, is surplus to requirements – tautology, in fact.

Walkers in the Howgills are certain to encounter springy turf underfoot almost everywhere, outcrops of rock being few and occurring only at Cautley Spout and in the confines of Carlin Gill. This is free-range country, where bosomy fells, unrestricted by walls and fences, and sporting surprisingly few trees, rise abruptly from glaciated valleys, their sides moulded into deep, shadowy gullies, and their tops a series of gentle undulations that shimmer in the evening light like burnished gold. This is a region inhabited by free-roaming cows, black-faced Rough Fell sheep and long-haired wild fell ponies, and is a delight to travel.

Three of the walks in this section (Walks 13–15) head for the highest point, The Calf, each by completely differing routes that reveal the best the Howgills have to offer, and encourage further independent exploration. Included, too, are three excellent walks that are neither truly Howgills nor wholly within the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Flanking the Eden valley are two outstanding and much neglected walks, including one that visits the source of both the River Ure and the Eden. Further north, Nine Standards Rigg is plumb on the Pennine watershed and enjoyably ascended from the market town of Kirkby Stephen.

WALK NINE

Hartley Fell and Nine Standards Rigg

| Start point | Kirkby Stephen NY775087 |

| Distance | 14.5km (9 miles) |

| Height gain | 540m (1770ft) |

| Grade | demanding |

| Time | 4–5hrs |

| Maps | Ordnance Survey OL19 (Howgill Fells and Upper Eden Valley) |

| Getting there | Plenty of parking in Kirkby Stephen |

| After-walk refreshment | Kirkby Stephen is well endowed with pubs and cafés |

‘Rigg’ means ‘ridge’, and so Nine Standards Rigg is the ridged summit of Hartley Fell, a short distance south-east of Kirkby Stephen and marginally outside the Yorkshire Dales National Park boundary. You can get bogged down, literally as well as metaphorically, if you try to shoehorn Hartley Fell into a ‘Pennine’ or ‘Dales’ category. It’s much more agreeable to ignore all that and to enjoy this airy saunter for its own merits. The whole of the ascent takes the line of the northern Coast to Coast walk; the onward route from Nine Standards Rigg lures you into the boggy clutches at the head of Whitsundale. But you don’t have to be drawn; you can simply go back the way you came.

Long Rigg on the lower slopes of Hartley Fell

The Route

Opposite the Pennine Hotel in Kirkby Stephen leave the Market Place by a short lane to the right of the churchyard and enter Stoneshot, bearing right and then left down steps to meet the River Eden at Frank’s Bridge. Cross the bridge and turn right to follow the river until it swings away to the right. From a gate, take to a surfaced path beside a wall and later a hedgerow, and continue to another gate in the top left corner of a field. Through this, go forward to arrive at the hamlet of Hartley.

Frank’s Bridge, Kirkby Stephen

Nine Standards

On reaching a minor road, cross diagonally left to a narrow path leading to a small bridge across Hartley Beck. A short way on, on joining another road, turn right. When the road shortly swings left, leave it on the apex for a brief path that remains with Hartley Beck a little longer before rejoining the road. Turn right again, and now climb easily to the entrance to Hartley Quarry.

The route passes close by the site of Hartley Castle, a medieval fortified house built in the 14th century and extended at the start of the 17th. There’s virtually nothing there now; by the late 18th century most of the original structure had been used to repair Eden Hall.

On passing the quarry, keep climbing and stick with the fell road, which gives fine retrospective views across the Vale of Eden to the high summits of the Pennines. A short descent leads past the entrance to Fell House Farm, and beyond this climb once more to the road end.

Just after the road end, branch left (for Rollinson Haggs) and soon pass through a gate. Go forward past the crags of Long Rigg and onto Hartley Fell. A broad track now leads on, and with the increasing elevation come ever-improving views. The track soon crosses Faraday Gill and then joins company with a wall on the right.

On the Faraday Gill path

Faraday Gill commemorates the local family whose offspring, Michael, was the English chemist and physicist who discovered electromagnetic induction and other important electrical and magnetic phenomena. Such was the regard in which Faraday was held, that it is said Albert Einstein kept a photograph of him on his study wall alongside Isaac Newton.

Continue as far as a branching path on the left that leads unerringly up to the conspicuous cairns on the summit ridge. Arrival here is quite special, not just for the views, but because the ridge lies along the Pennine and British watershed.

No one has yet come up with a valid explanation for the Nine Standards – the monoliths found on the summit. They stand on the former county boundary between Westmorland and the North Riding of Yorkshire, and that may be explanation enough, but unlikely given the effort involved. Happily, after a prolonged period of neglect, the cairns have seen much restoration in recent years and are worthy of heritage protection.

The cairns have long been dismissed as late medieval at best, but recent research has shown that the nine cairns appear on old maps, and reference has been found in documents from the Brough Court indicating their existence as early as 1507, and possibly much earlier. Low-level oblique aerial photographs of the summit reveal the possible outline of a rectangular enclosure with the cairns running diagonally through it, and this may indicate some underlying archaeology.

On a fine day there are few vantage points that provide a wider or more inspiring panorama over wild moorlands. The highest point of the summit ridge is actually at the nearby trig pillar, but the view from there is nothing like so impressive.

The onward route continues past the trig pillar into conflict with rough, boggy, heathery, tussocky moorland, with many variable peat bogs to circumnavigate. If you don’t fancy this, then simply retrace your outward route.

Otherwise continue past the trig pillar, descending to an extended boggy area on the very edge of the national park (NY827057). Here the Coast to Coast route turns east, heading down into Whitsundale, but this walk turns west (right), although there is no path for a while. Maintain a westerly direction and soon a large cairn is seen off to the south-west. It is important to keep north of this; don’t be drawn towards it. Eventually pass scattered rocky outcrops and a wide grassy channel through peat. These are Rollinson Haggs, beyond which a signpost is encountered on the line of a bad-weather route for the Coast to Coast (NY817058).