Читать книгу Walking on the Isle of Man - Terry Marsh - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

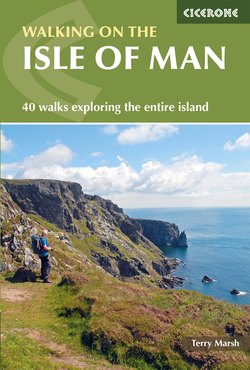

The northern tip of the island seen from the Millennium Way above Ramsay

For most people, the Isle of Man is an enigma: often heard, sadly, is the comment ‘I’ve always wanted to go, but never got round to it’.

Few would think of the island as a walker’s paradise – yet it is, as this book will demonstrate. Fewer still know anything about the island, save that it has an annual motorcycle race of some severity, that it is something of a tax haven, that Manx cats have no tails, and (I’m pushing it now) the island’s bishop has the title ‘Bishop of Sodor and Man’. Very few could explain the way the island is governed: is it part of Britain? (no); the United Kingdom? (no); the Commonwealth, then? (yes). Yet, the Isle of Man is at the very centre (give or take) of the British Isles, roughly equidistant from the other countries. Indeed, they say that on a clear day it is possible to see seven kingdoms: England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Man, and the kingdoms of Heaven and the Sea.

About the Isle of Man

The name of the island has some interesting derivations. Julius Caesar mentions an island ‘In the middle of the Channel’ (by which he meant the Irish Sea), which he called ‘Mona’, a name also associated with Anglesey, off the North Wales coast. This confusion wasn’t eased when Pliny the Elder, writing in AD74, listed the islands between Britain and Ireland, and included Mona, by which he probably meant Anglesey, and Monapia, which is thought to have been the Isle of Man. Paulus Orosius (circa AD400) refers to ‘Menavia’, a place ‘of no mean size, with fertile soil, inhabited by a tribe of Scots’. The geographer who visited Britain at the time of Hadrian called the island ‘Monaoida’, while an Irish monk, Nennius (AD858), refers to ‘Eubonia’. Later still, the Irish and Welsh forms become more consistently used, ‘Mannan’ and ‘Mannaw’ respectively. The first name-form occurring on the island is on a runic cross in Kirk Michael, ‘Maun’. Today, it is known as ‘Mannin’, ‘Vannin’ or ‘Ellan Vannin’, the island of Man. Those of a more romantic inclination, however, will opt for the view that the name refers to a Celtic sea god, Manannan, the equivalent of the Roman sea god, Neptune, or the Greek, Poseidon.

Above Sulby Reservoir (Walk 7)

An island in the Irish Sea, situated mid-way between England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, the Isle of Man has a land mass of some 572km2 (221 square miles) and measures, at its extremities, 52km (32½ miles) by 22km (13¾ miles). Geographically it is part of the British Isles, a dependency of the British crown, but it is not part of the United Kingdom. The capital is Douglas, and other towns of size are Ramsey, Peel and Castletown. Government of the island is through the 24 representatives of the House of Keys and a nine-member legislative council, which together make up the Court of Tynwald (the oldest surviving parliamentary body in continuous existence in the world), passing laws subject to the royal assent. Laws passed at Westminster only affect the island if adopted by Tynwald.

The principal industries are light engineering, agriculture, fishing, tourism, banking and insurance. The island, which has a population of 86,683 (2014), produces its own coins and notes in UK currency denominations, and while UK money can be used on the island, Manx notes are not accepted in the UK. The language is English, though there is a true Manx language, closer to Scottish than Irish Gaelic, which almost died out last century but which has increased in popularity recently. Today, Manx Gaelic is spoken by 2.2 per cent of the total population, a figure which rises to 6.5 per cent in the north of the island.

What the island lacks in size it makes up for in its variety of scenery, which reflects almost every type of landscape found elsewhere in the British Isles, from open moorland to thickly wooded glens, sandy beaches to bare mountain tops, limestone spreads to volcanic basalts. The principal rivers are the Santon, the Silver Burn, the Neb-Thenass, the Sulby and the Dhoo and Glass (ie Douglas). Within the 160km (99 miles) of coastline lies a central range of mountains and hills running north-easterly/south-westerly, from which well-defined valleys descend to cliffs and sheltered bays. In the north of the island the landscape is flat and crossed by slow-moving rivers and streams that debouche onto long sandy beaches. Cutting obliquely across the island, generally at right angles to the main axis, is a central valley with Peel at its western end and Douglas at its eastern.

The watershed, or water-parting, which follows the north-east–south-west axis, has long been important as the fundamental line of separation of the island into ‘Northside’ and ‘Southside’ – though this is not the division used in this book, which settles for the much more prosaic division based on the trans-island A1 road. Traditionally, Northside has included the ‘sheadings’ (districts) of Glenfaba, Michael and Ayre, while Southside embraced Garff, Middle and Rushen sheadings. Changes in 1796 modified the original pattern by making Northside include Michael, Ayre and Garff, and Southside, Glenfaba, Rushen and Middle – a more geographically accurate division.

History and culture

The earliest evidence for man’s settlement on the island comes from the Mesolithic period, a time when, quite probably, the island still formed part of the British ‘mainland’. By Neolithic times (about 6000–4500 years ago), Man was an island, and its people lived around the coastal plains in areas that were covered by predominantly oak woodlands.

During the Bronze Age (about 4000 years ago), trade in gold ornaments and bronze artefacts extended across Europe, and the Isle of Man clearly played a part in this trade. Towards the end of this period, the climate changed noticeably and for a while the development of the island slowed down, only regaining momentum with the development of Christianity. This was a time when the Romans populated much of Britain, though they never occupied Man, in spite of the probability that they must have passed close to it en route with supplies for the garrison manning Hadrian’s Wall, and quite possibly glimpsed it as they trekked to and from their Lakeland fort at Hardknott.

Close contact with Man and the Atlantic coast of Britain continued after the Romans retreated. During this time, between the 5th and 8th centuries, it is probable that the Isle of Man featured in the itineraries of many Christian missionaries. St Bridget, St Ninian, St Patrick, St Columba and St Cuthbert all figure in church dedications on the island, so it is not too fanciful to suppose that they must have arrived here at some time during their lifetimes.

Tower, Rushen Abbey

The scene altered significantly with the conquest of the island by Vikings. This brought about many changes in ethnic make-up, religion and cultural identity. Although pagan at the outset, the Norse quickly succumbed to the influence of Christianity. This, in turn, fostered the propagation of a unique blend of Celtic and Norse influences. The most notable survivor from this period is the Norse annual open-air assembly, the ‘Thing’, at which new laws were announced and disputes settled. In the Norse language, the place for a meeting was a vollr, hence Thing-vollr, has become Tynwald, the island’s unique focus of government.

During this Scandinavian period the Isle of Man became the capital of an island realm – the Kingdom of the Isles – that embraced all the Hebrides, ruled by a Manx king subordinate to Norwegian sovereignty, with its headquarters on St Patrick’s Isle, today linked to Peel by a substantial causeway. In a religious context, this became known as Ecclesia Sodorensis, a separate diocese, its name based on the Norse for Man and the Hebrides (‘the Southern Isles’). In 1266 the Hebrides were ceded to Scotland, heralding the political break-up of the Kingdom of the Isles, but the religious ties continued for much longer and, though long since severed, there is a reminder of this past regime in the title of the Manx Bishop of Sodor and Man.

For over 100 years, sovereignty of the Isle of Man was disputed between the English and the Scots, with the former ultimately gaining control in 1405 when sovereignty was granted to Sir John Stanley. His descendants – Earls of Derby and Dukes of Atholl – ruled Man for over 300 years, bringing a period of consolidation during which the island became increasingly isolated. This enabled the development of its own form of government, language and personal names. Trade was not encouraged, indeed strictly regulated, and visitors were kept away. The language of the people was Manx – though the well-to-do and government officials spoke English. Castletown was the capital of the island and the place of the lord’s residence, finally being displaced in favour of Douglas only in 1869.

During the 17th century, conditions started to change rather radically as ‘the running trade’ – smuggling – took hold. Man’s strategic position, helped by its low custom duties, made it ideal for this form of activity, which grew to such proportions that by the 18th century it became necessary for the British government to ‘take control’ by introducing the Revesting and Mischief Act in 1765. These effectively meant that sovereignty of the island was once more vested in the Crown, and smuggling was curtailed.

The ‘Revestment’ was a humiliation and an economic disaster for the Manx people, for although Tynwald still remained, it could pass no laws costing money because the customs duties were diverted to the British government. This situation continued until 1866, when the Manx customs revenue was transferred back to the island’s revenue, but with the stipulation that ultimate control over spending should rest with the British Treasury. This situation was only repealed in 1958, since when the island has had the freedom to conduct its own affairs.

Geology and vegetation

The bulky upland mass of the island is a much-mangled thrust of old slaty rocks, known as the Manx slate series, consisting of clay slates, grits and greywackes, probably Ordovician, rather like the Skiddaw slates of the English Lake District, which also re-appear in the south-west of that region. The slates were refolded several times during the Caledonian mountain-building period and outcrop now in the axis of the island. During this time, the rock mass was penetrated by molten material that formed dykes, most noticeable along the coast, where the slates or grits are exposed.

During Carboniferous times the limestone that proliferates around Castletown (especially at Scarlett Point) and Port St Mary were laid down. Near Peel, distinctive red sandstone provides an easily workable material for building stone and appears, along with Castletown limestone, in many buildings on the island.

Solid rocks at surface level are rare, though Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic deposits lie beneath the lowlands at the northern end of the island, covered by glacial drift to a depth of 50m (164ft) or more.

The Bay at Port Cornaa (Walk 11)

Three successive glacial periods are thought to have affected the island, with glacial deposits most noticeable in the north, but still significant elsewhere. The ice sheets came mainly from south-west Scotland and north-east Ireland, and boulder clays, along with sands and gravels, are distributed over much of the island.

An unusual feature of the Manx landscape, something that has existed for centuries, is the almost complete absence of trees. It is clear that when humans first arrived, the coastal lands would have been covered in oak woods, but today trees only occur in the sheltered glens and in recently re-afforested areas.

A wealth of wild flowers

The immense diversity of habitat on the Isle of Man generates a range of flora and fauna bordering on the spectacular. There are wild flowers throughout the year, from the primroses, celandine, sorrel and wood anemones of spring, when rafts of wild garlic are already filling the air with their pungent smell and bluebells (blue, white and pink in hue) are starting to carpet whatever remaining stands of woodland they can find. Gorse is already in heady, scented bloom come early April, when the delicate coastal squill, sea campion and thrift are also starting to flower. Orchids flourish in June, while the heathers that bring a purple hue to the Manx hillsides start to flower from July onwards.

Later in the year, into autumn, a few sheltered woodland spots start to produce fungi as the great colour change of the year begins. Throughout the year it is impossible not to notice the luxuriant growth of lichens, mosses and liverworts – clear indicators of a clean and healthy climate.

Cattle at Port Grenaugh

Birdlife

The island is well suited to birdlife, and a free leaflet from tourist information centres tells you where to look, and when, for the island’s most interesting species.

You may be able to spot red-throated, black-throated and great northern divers, Manx shearwater, storm petrel, water rail, hen harrier, bar-tailed godwit, long- and short-eared owls, siskin, redpoll, crossbill and chough. See Appendix C for information about the work of the Manx Wildlife Trust.

Climate

Because of the influence of the Irish Sea, the Manx climate is temperate and lacking in extremes. In winter, snowfall and frost are infrequent. On rare occasions snow does occur, but seldom lies for more than a day or two. February tends to be the coldest month, with an average daily temperature of 4.9°C (41°F), but it is also often dry. However, the island is rather windy. The prevailing wind direction for most of the island is from the south-west, although the complex topography means that local effects of shelter and exposure are very variable. April, May and June are the driest months, while May, June and July are the sunniest. July and August are the warmest months, with an average daily maximum temperature around 17.6°C (63°F). The highest temperature recorded at the island’s weather centre at Ronaldsway is 28.9°C, or 84°F. Thunderstorms are infrequent and short-lived.

Although geographically small, there is, nevertheless, significant climatic variation around the island. Sea fog affects the southern and eastern coasts at times, especially in spring, but is less frequent in the west. Rainfall and the frequency of hill fog both increase with altitude. The highest point of the island – Snaefell at 621m (2036ft) – receives some 2¼ times more rainfall than Ronaldsway, on the south-east coast, where the annual average is 863mm (34ins).

Niarbyl (Walk 23)

The Three Legs of Man

No one really knows how the Three Legs of Man motif, the symbol of independence, came to be adopted as the national emblem of the Isle of Man. The three-legged device certainly has a long history, dating far back into pagan times, and represents the sun and its daily passage across the heavens. The Manx form was derived from a design that showed the spokes of a wheel and which, in turn, represented the rays of the sun. This has led to it being described as a solar wheel, a symbol of pagan sun worship. Other related symbols include the cross and the fylfot, or four-legged swastika.

It is believed that Alexander III of Scotland may have adopted it when he gained control of the Isle of Man following the defeat of King Haakon of Norway at Largs in 1263 and the end of Norse rule that followed. Credence is given to this notion by the fact that the seal of King Harald Olaffson, granting a mining charter to the monks of Furness Abbey in 1246, still bore a ship emblem as its seal, not the Three Legs motif. The oldest representation of the Three Legs in existence is on the Manx Sword of State, and there is another use on the Maughold Market Cross, now in St Maughold’s Church.

St Michael’s Island (Walk 40)

Getting there

It might be worth checking the sporting calendar before beginning to plan your trip, as the famous TT (Tourist Trophy) motorbike race and the Grand Prix rather take over the island when they’re on, and there are other races throughout the year. The main TT weeks are late May/early June and the Grand Prix is late August/early September.

By air

Frequent flights are provided to and from London (Gatwick, Heathrow and Southend), Manchester, Liverpool, Bristol, Blackpool, Birmingham, Glasgow, Gloucester, Leeds/Bradford, Jersey and Dublin. There are also connecting flights linking the island to Newcastle, Edinburgh, East Midlands and Southampton and to many international destinations.

On arrival on the island, you are greeted with a very modern airport terminal, with an assortment of shops, café, seating areas and telephones. Security checks exist, as in all UK national airports. In addition, flights to and from Ireland are subject to duty free allowances.

Getting through the airport is relatively quick compared to UK airports. Immediately outside the airport terminal is the main bus route and stop for travelling to Douglas and the south. Inside the terminal are a number of car hire firms.

By sea

The island’s principal port is Douglas, which has deep-water berths and facilities for handling passengers, cars and freight vehicles and general cargoes. Peel, on the west coast, has a deep-water berth and facilities for handling limited passenger traffic and general cargoes. Ramsey in the north-east is a drying harbour with a busy trade in general and bulk cargoes.

The island’s main sea routes are between Douglas and Liverpool, and Douglas and Heysham, a modern port in the north-west of England closely linked to Britain’s motorway and intercity rail networks. The Isle of Man Steam Packet Company operates multi-purpose and freight RORO vessels on the Heysham route, providing twice-daily services throughout the year for passengers, cars and freight vehicles. The Steam Packet Company also has twice-daily fast craft services from Liverpool from April to October and conventional weekend services during the winter.

In the summer months the Steam Packet operates additional fast craft routes for holiday traffic to Dublin and Belfast, as well as extra sailings to Heysham and Liverpool with SeaCat and SuperSeaCat fast craft.

Getting about

By car or motor bike

Driving around the island is generally relaxed and enjoyable. Typical A- and B-roads, together with country lanes, prevail. Speed limits vary across the island, and the best advice is to stay below 30mph in built-up areas and 50mph elsewhere.

Many of the roads and lanes are narrow and twisting, and must be negotiated with care. It is an offence, as it is in the UK, to use a hand-held mobile phone while driving. Seatbelt laws apply on the island as they do throughout the UK. All vehicles must be insured and you should have your driving licence with you. Although not mandatory, it’s advisable to have vehicle breakdown cover, and a first aid kit, warning triangle and fire extinguisher.

Parking discs, available free from a number of locations, including the Sea Terminal Building, are required in the larger towns and villages. Disc parking zones, which are clearly signed, range from 15 minutes to two hours. Trailer caravans are not permitted on the island, but tenting campers and self-propelled motor caravans are welcome.

Because of the wide range of events held on the island each year, there are times when many of the roads will be closed for short periods. Information about road closures and events can be obtained from the Welcome Centre at the Sea Terminal Building.

Steam train

Running in the summer season (Easter to September) from Douglas to Port Erin, the steam train takes about 1 hour for the journey, with several stations to stop off on the way. Tickets are available from the main stations. Douglas Station is about 10 minutes’ walk from the Sea Terminal.

Horse-drawn tram

The horse-drawn trams complete a circuit along Douglas promenade, from outside the Sea Terminal to Derby Castle at the opposite end of the promenade. These operate during the summer season only. Travel time is approximately 30 minutes each way. Tickets can be purchased on board.

Electric train

The Manx Electric Railway operates all year round, except Christmas week, from Douglas promenade (Derby Castle) all the way to Laxey. You then have a choice to continue to Ramsey or (summer only) take the alternative route up Snaefell on the Snaefell Mountain Railway branch line.

The time to Laxey is about 30 minutes. From there to Ramsey is about the same, and the trip to the summit of Snaefell takes about 40 minutes.

Bus

A national bus service operates throughout the island, connecting all the towns, villages and district areas. The frequency of the different services depends very much on the nature of the destination and the departure points. Prices are relatively cheap and multi-day passes can be purchased. Isle of Man resident OAPs travel for free – but there are no concessions for visiting pensioners.

Taxi

There are taxi ranks in all the main urban centres.

Car hire

Hire cars are available at the Sea Terminal, the airport terminal, delivered to your hotel or picked up at certain garages. Booking is advised. You will need to be 21 or over, have a valid driving licence and possibly your passport.

Accommodation

There is a wide range of excellent accommodation, from prime hotels to inexpensive B&Bs and self-catering properties right across the island, though there are no hostels as such, and few campsites. All the walks in this book were completed from bases at Orrisdale (Kirk Michael) and Colby Glen (First edition), and Crosby (Second edition), but the island’s road and public transport network is such that it matters not which town or village is used.

Looking across the bay to Bradda Hill (Walk 30)

Walking and access

The scope for walking on the island is considerable, and with a very distinctive flavour. Being an island, and a smallish one at that, many walks touch upon the coastline at some point, and it is almost true to say that on every walk in this book you can see the sea at some stage. It is equally valid that with few exceptions all the footpaths are well signed, whether it is for the normal paths or one (or more) of the long- and middle-distance trails that criss-cross the island.

There is limited opportunity for walks in excess of, say, 16km (10 miles), though the diligent person can string together quite a few smaller walks to make something more demanding. So, the emphasis here is on shorter walks, suitable for half days, or for families. More committed walkers will still find they can spend long days crossing the hills that form the central spine of the island, but the number of opportunities to do so is limited. Even so, you can come here for a month and still follow a new walk every day.

And being so close to the sea produces its own brand of weather conditions for the walker to contend with – from hot balmy days to real howlers on the tops. Sea mist can be quite a problem, too, so if you can’t navigate in poor visibility, it would be a good idea to wait for a clear day.

As in the UK great swathes of the Isle of Man are open access, here known as ‘Public Ramblage’. In essence this means there is a freedom to roam at will. Large parts of the high ground fall within this definition. Other areas hold ‘Scenic Significance’ or are held by the Manx National Trust or Manx National Heritage, and here access is generally not a problem, though there may be local restrictions.

Elsewhere, the island has 17 National Glens, maintained and preserved by the Forestry Department, because it is largely in the glens that the island’s main areas of tree cover are to be found. There are two types of glen, coastal and mountain. The coastal glens – like Glen Maye, Groudle Glen, Glen Wyllin and Dhoon Glen – often lead down to a beach, while the mountain glens – Sulby, Glen Mooar, Colby Glen – have splendid streams, waterfalls and pools.

Spread across the island is a network of ‘Greenway Roads’ and ‘Green Lanes’. A Green Lane is an unsurfaced road through the countryside for pedestrians, 4x4s, motorcycles, mountain bikes and horses, similar to a Byway Open to All Traffic in England. Some are ‘Greenway Roads’ which have restrictions. On Green Lanes, vehicle users should give way to pedestrians and horse riders, and be aware that farm animals may be in the road at any time.

Mapping

One of the problems, probably the only significant problem, for walkers visiting the island is the mapping. The British Ordnance Survey produces a single Landranger map (Sheet 95), at a scale of 1:50,000, and experienced walkers will find this adequate. But, at the time of writing the first edition, there was no corresponding larger scale OS map. What existed was a two-sheet 1:25,000 Outdoor Leisure Map produced by the Isle of Man by reducing old six-inch maps. The result was often text too small to read with the naked eye, although rights of way were clearly depicted. This has been replaced by a more modern map which is a little better in this respect. A modern 1:30,000 map, produced by Harvey Maps, is probably the best map for walkers.

Using this guide

Walking across Maughold Brooghs (Walk 10)

The walks range across the whole island and are grouped, roughly equally, North or South, on no stronger relationship than that they have with the A1 Douglas to Peel road. There is no other geographical significance to the grouping.

The descriptions in this guidebook all follow the same format. The information box gives the stage start and finish location accompanied by grid references, stage distance (km/miles), height gain, details of places close to the route that offer refreshments and hints on parking.

The map extracts which accompany each route are taken from the 1:50,000 OS mapping, blown up to 1:40,000 for greater clarity. A summary table of all walks in the guidebook, to help you select the most convenient route for you and your walking party, can be found in Appendix A.