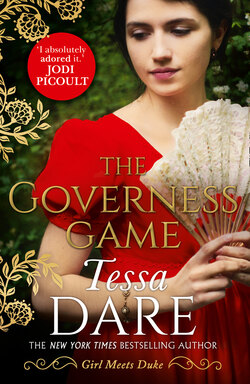

Читать книгу The Governess Game - Tessa Dare - Страница 17

Chapter Eight

ОглавлениеThe education was on hold. Before any lessons could take place, Alexandra had a ten-year-old girl to conquer.

After breakfast, the Rosamund Rebellion commenced.

Silence was her first strategy, and she’d marshaled Daisy into the campaign. Neither of them would speak a word to Alex. Indeed, once the funeral was over, neither of them even acknowledged her presence. Rosamund read her book, Daisy exhumed Millicent, and all three treated Alex as if she didn’t exist.

Very well. Both sides could play at this game.

The next day, Alex didn’t even try to start conversation. Instead, she brought a novel and a packet of biscuits—Nicola had sent her off with a full hamper of them—and she sat in the rocking chair to read. She laughed aloud at the funny bits—really, pigeons?—gasped at the revelations, and loudly chewed her way through a dozen biscuits. At one point, she was certain she felt Daisy gazing at her from across the room. However, she didn’t dare look up to confirm it.

It became a habit. Every day, Alex brought with her a novel, and every day, a different variety of Nicola’s biscuits. Lemon, almond, chocolate, toffee. And every day, as she sat eating and reading, the girls ignored her existence.

Until the morning a foul odor permeated the nursery. A sharp scent that even fresh-baked biscuits had no hope to overpower. As the day grew warmer, the ripe, pungent smell became nauseating. The girls offered no clue as to its origin, and Alexandra would not give Rosamund the satisfaction of asking. Instead she sniffed and searched until she found the source. A bit of clammy, shrunken Stilton buried in her bottom-most desk drawer.

Well, then. It would seem the tactics were escalating. She could rise to the challenge.

Alex had exhausted her supply of biscuits. She brought in a new box of watercolors, bright as jewels in a treasure chest, placing them in easy reach.

The girls dusted her chair with soot.

Alex brought in a litter of kittens Mrs. Greeley was evicting from the cellar. No one could resist fluffy, mewling kittens. And Daisy almost didn’t, until Rosamund yanked her away with a stern word.

That evening, a rotting plum mysteriously appeared in Alex’s slipper—and unfortunately, her bare toes found it.

Rosamund seemed to be daring her to shout or rage, or go complaining to Mr. Reynaud. However, Alex refused to surrender. Instead, she smiled. She allowed the girls to do as they pleased. And she waited.

When they were ready to learn, they would tell her so. Until then, she would only be wasting her effort.

At last, her patience was rewarded. She found her opening.

Rosamund fell asleep on a particularly warm afternoon, dozing off with her book propped on her knees and her head tilted against the window glazing. Alex motioned Daisy closer and laid out a row of wrapped sweetmeats on the table, one by one.

“How many are there?” she whispered. “Count them out for me, and you may have them for yourself.”

Daisy sent a cautious glance toward her sister.

“She’s sleeping. She’ll never know.”

With a small, uncertain finger, Daisy touched each sweet as she counted aloud. “One. Two. Three. Four. Five.”

“And in this group?”

Daisy’s lips moved as she counted them quietly to herself. “Six.”

“Well done, you. Now how many in both groups together? Together, five and six are . . . ?”

“Daisy,” Rosamund snapped.

Startled, Daisy snatched her hand behind her back. “Yes?”

“Millicent’s vomiting up her innards. You’d better see to her.”

As her sister obediently retreated, Rosamund approached Alexandra. “I know what you’re doing.”

“I never imagined otherwise.”

“You won’t win.”

“Win? I’m not certain what you mean.”

“We will not cooperate. We are not going away to school.”

Alex softened her demeanor. “Why don’t you want to go to school?”

“Because the school won’t want us. We’ve been sent down from three schools already, you know.”

“Don’t say you’d rather remain here with Mr. Reynaud. If it were up to him, you’d have only dry toast at every meal.”

“We’re not wanted by Mr. Reynaud, either. No one wants us. Anywhere. And we don’t want them.”

Alexandra recognized the defiance and mistrust in the girl’s eyes. A dozen years ago, those eyes could have mirrored her own.

A tender part of her wanted to clutch the girl close. Of course you’re wanted. Of course you’re loved. Your guardian cares for you so very much. But to lie would be taking the coward’s way out, and Rosamund wouldn’t be fooled. What the girl needed wasn’t false reassurance—it was for someone to tell her the honest, unflinching truth.

“Very well.” Alex folded her hands on the desk and faced her young charge. “You’re right. You’ve been passed around from relation to relation, sent down from three schools, and Mr. Reynaud wishes to rid himself of you at the first opportunity. You’re unwanted. So what you must decide is this: What do you want?”

Rosamund gave her a suspicious look.

“I was orphaned, too. A bit older than you are now, but I was utterly alone in the world, save for a few distant relations who paid for my schooling—on the condition that they would never have me in their sight. It wasn’t fair. It was lonely, and my schoolmates were cruel, and I cried myself to sleep more evenings than not. But in time, I realized I had an advantage over the other girls. They had to worry about catching a husband to help their families. I was indebted to no one, I answered to no one, and I needn’t meet anyone’s expectations of what a young lady should or shouldn’t be. My life was my own. I could follow any dream, if I was prepared to work hard for it. Do you hear what I’m saying?”

Rosamund gave no acknowledgment, but Alex could tell the girl was listening. Intently.

“So what is it you truly want? If you could have any life you wished, what would it be?”

“I want to escape. Not just this house, but England.”

“Where do you mean to go?”

“Anywhere. Everywhere. I’d take Daisy with me. We’d travel the world, wearing trousers and smoking cheroots and doing as we pleased.”

Alexandra had been hoping to hear “I want to be a painter.” Or a French-trained chef, or an architect. Whatever pursuit Rosamund named, Alex could build lessons on its foundation. But she was quite certain Mr. Reynaud would not approve of lessons in cheroot-smoking. Alex wouldn’t have known how to give them, anyway.

“That sounds like a grand life indeed,” she said, “but how will you support yourselves?”

“I’m perfectly capable of looking after us both.” Rosamund cast a glance at the table. “So you can clear away your nine sweets and leave us alone.”

“You know very well there are eleven sweetmeats.”

“Are there?”

Alex looked. Sure as could be, two sweetmeats were missing. The girl had managed to steal them, right from under her nose, and one of the two was already across the room in Daisy’s hands. Alex could hear the paper crinkling as the younger girl unwrapped it.

“Rosamund, may I tell you something? You will find yourself reluctant to believe it, but it’s the truth.”

The girl gave a lackadaisical shrug. The warmest gesture she’d made toward Alex so far.

“I like you,” Alexandra said. “I like you very much indeed.”