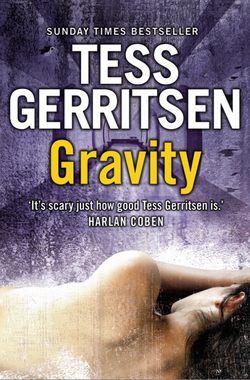

Читать книгу Gravity - Тесс Герритсен, Tess Gerritsen - Страница 10

3

ОглавлениеJuly 10

Dr Jack McCallum heard the scream of the first ambulance siren and said, ‘It’s show time, folks!’ Stepping outside to the ER loading dock, he felt his pulse kick into a tachycardia, felt the jolt of adrenaline priming his nervous system into crackling live wires. He had no idea what was coming to Miles Memorial Hospital, only that there was more than one patient on the way. Over the ER radio they’d been told a fifteen-car pileup on I-45 had left two fatalities at the scene and a score of injured. Although the most critical patients would be taken to Bayshore or Texas Med, all the area’s smaller hospitals, including Miles Memorial, were braced for the overflow.

Jack glanced around the ambulance dock to confirm his team was ready. The other ER doctor, Anna Slezak, stood right beside him, looking grimly pugnacious. Their support staff included four nurses, a lab runner, and a scared-looking intern. Only a month out of med school, the intern was the greenest member of the ER team and hopelessly fumble-fingered. Destined for the field of psychiatry, thought Jack.

The siren cut off with a whoop as the ambulance swung up the ramp and backed up to the dock. Jack yanked open the rear door and got his first glimpse of the patient—a young woman, head and neck immobilized in a cervical collar, her blond hair matted with blood. As they pulled her out of the ambulance and he got a closer look at her face, Jack felt the sudden chill of recognition.

‘Debbie,’ he said.

She looked up at him, her gaze unfocused, and did not seem to know who he was.

‘It’s Jack McCallum,’ he said.

‘Oh. Jack.’ She closed her eyes and groaned. ‘My head hurts.’

He gave her a comforting pat on the shoulder. ‘We’ll take good care of you, sweetheart. Don’t worry about a thing.’

They wheeled her through the ER doors, toward the trauma room.

‘You know her?’ Anna asked him.

‘Her husband’s Bill Haning. The astronaut.’

‘You mean one of the guys up on the space station?’ Anna laughed. ‘Now, there’s a long distance phone call.’

‘It’s no problem reaching him, if we have to. JSC can put a call right through.’

‘You want me to take this patient?’ It was a reasonable question to ask. Doctors usually avoided treating friends and family; you cannot remain objective when the patient in cardiac arrest on the table is someone you know and like. Although he and Debbie had once attended the same social functions, Jack considered her merely an acquaintance, not a friend, and he felt comfortable acting as her physician.

‘I’ll take her,’ he said, and followed the gurney into the trauma room. His mind was already leaping ahead to what needed to be done. Her only visible injury was the scalp laceration, but since she had clearly suffered trauma to her head, he had to rule out fractures of the skull and cervical spine.

As the nurses drew blood for labs and gently pulled off the rest of Debbie’s clothing, the ambulance attendant gave Jack a quick history.

‘She was about the fifth car in the pileup. Far as we could tell, she got rear-ended, her car spun sideways, and then she got hit again, on the driver’s side. Door was caved in.’

‘Was she awake when you got to her?’

‘She was unconscious for a few minutes. Woke up while we were putting in the IV. We got her spine immobilized right away. BP and heart rhythm have been stable. She’s one of the lucky ones.’ The attendant shook his head. ‘You should’ve seen the guy behind her.’

Jack moved to the gurney to examine the patient. Both of Debbie’s pupils reacted to light, and her extraocular movements were normal. She knew her own name and where she was, but could not recall the date. Oriented only times two, he thought. It was reason enough to admit her, if only for overnight observation.

‘Debbie, I’m going to send you for X rays,’ he said. ‘We need to make sure you haven’t fractured anything.’ He looked at the nurse. ‘Stat CT, skull, and C-spine. And…’ He paused, listening.

Another ambulance siren was approaching.

‘Get those films done,’ he ordered, and trotted back outside to the loading dock, where his staff had reassembled.

A second siren, fainter, had joined the first wail. Jack and Anna glanced at each other in alarm. Two ambulances on the way?

‘It’s going to be one of those days,’ he muttered.

‘Trauma room cleared out?’ asked Anna.

‘Patient’s on her way to X-ray.’ He stepped forward as the first ambulance backed up. The instant it rolled to a stop, he yanked open the door.

It was a man this time, middle-aged and overweight, his skin pale and clammy. Going into shock was Jack’s first assessment, but he saw no blood, no signs of injury.

‘He was one of the fender benders,’ said the EMT as they wheeled the man into the treatment room. ‘Got chest pain when we pulled him out of his car. Rhythm’s been stable, a little tachycardic, but no PVCs. Systolic’s ninety. We gave morphine and nitro at the scene, and oxygen’s going at six liters.’

Everyone was right on the ball. While Anna took the history and physical, the nurses hooked up the cardiac leads. An EKG blipped out of the machine. Jack tore off the sheet and immediately focused on the ST elevations in leads V1 and V2.

‘Anterior MI,’ he said to Anna.

She nodded. ‘I figured he was a tPA special.’

A nurse called through the doorway, ‘The other ambulance is here!’

Jack and two nurses ran outside.

A young woman was screaming and writhing on the stretcher. Jack took one look at her shortened right leg, the foot rotated almost completely sideways, and knew this patient was going straight to surgery. Jack quickly cut away her clothes, to reveal an impacted hip fracture, her thigh bone rammed into the socket by the force of her knees hitting the car’s dashboard. Just looking at her grotesquely deformed leg made him queasy.

‘Morphine?’ the nurse asked.

He nodded. ‘Give her as much as she needs. She’s in a world of hurt. Type and cross six units. And get an orthopod in here as soon as—’

‘Dr McCallum, stat, X-ray. Dr McCallum, stat, X-ray.’

Jack glanced up in alarm. Debbie Haning. He ran out of the room.

He found Debbie lying on the X-ray table, hovered over by the ER nurse and the technician.

‘We’d just finished doing the spine and skull films,’ said the tech, ‘and we couldn’t wake her up. She doesn’t even respond to pain.’

‘How long’s she been out?’

‘I don’t know. She was lying on the table ten, fifteen minutes before we noticed she wasn’t talking to us anymore.’

‘Did you get the CT scan done?’

‘Computer’s down. It should be up and running in a few hours.’

Jack flashed a penlight in Debbie’s eyes and felt his stomach go into a sickening free fall. Her left pupil was dilated and unreactive.

‘Show me the films,’ he said.

‘C-spine’s already up on the light box.’

Jack swiftly moved into the next room and eyed the X rays clipped to the backlit viewing box. He saw no fractures on the neck films; her cervical spine was stable. He yanked down the neck films and replaced them with the skull X rays. At first glance he saw nothing immediately obvious. Then his gaze focused on an almost imperceptible line tracing across the left temporal bone. It was so subtle it looked like a pin scratch on the film. A fracture.

Had the fracture torn the left middle meningeal artery? That would cause bleeding inside her cranium. As the blood accumulated and pressure built up, the brain would be squeezed. It explained the rapid deterioration of her mental status and the blown pupil.

The blood had to be drained at once.

‘Get her back to ER!’ he said.

Within seconds they had Debbie strapped to the gurney and were wheeling her at a run down the hallway. As they swung her into an empty treatment room, he yelled to the clerk, ‘Page neurosurgery stat! Tell them we have an epidural bleed, and we’re prepping for emergency burr holes.’

He knew what Debbie really needed was the operating room, but her condition was deteriorating so quickly they had no time to wait. The treatment room would have to serve as their OR. They slid her onto the table and attached a tangle of EKG leads to her chest. Her breathing had turned erratic; it was time to intubate.

He had just torn open the package containing the endotracheal tube when a nurse said, ‘She’s stopped breathing!’

He slipped the laryngoscope into Debbie’s throat. Seconds later, the ET tube was in place and oxygen was being bagged into her lungs.

A nurse plugged in the electric shaver. Debbie’s blond hair began to fall to the floor in silky clumps, exposing the scalp.

The clerk poked her head in the room. ‘Neurosurgeon’s stuck in traffic! He can’t get here for at least another hour.’

‘Then get someone else!’

‘They’re all at Texas Med! They’ve got all the head injuries.’

Jesus, we’re screwed, thought Jack, looking down at Debbie. Every minute that went by, the pressure inside her skull was building. Brain cells were dying. If this was my wife, I wouldn’t wait. Not another second.

He swallowed hard. ‘Get out the Hudson brace drill. I’ll do the burr holes myself.’ He saw the nurses’ startled looks, and added, with more bravado than he was feeling. ‘It’s like drilling holes in a wall. I’ve done it before.’

While the nurses prepped the newly shorn scalp, Jack put on a surgical gown and snapped on gloves. He positioned the sterile drapes and was amazed to find his hands were still steady, even while his heart was racing. It was true he had drilled burr holes before, but only once, and it was years ago, under the supervision of a neurosurgeon.

There’s no more time. She’s dying. Do it.

He reached for the scalpel and made a linear incision in the scalp, over the left temporal bone. Blood oozed out. He sponged it away and cauterized the bleeders. With a retractor holding back the skin flap, he sliced deeper through the galea and reached the pericranium, which he scraped back, exposing the skull surface.

He picked up the Hudson brace drill. It was a mechanical device, powered by hand and almost antique looking, the sort of tool you might find in your grandfather’s woodshop. First he used the perforator, a spade-shaped drill bit that dug just deeply enough into the bone to establish the hole. Then he changed to the rose bit, round-tipped, with multiedged burrs. He took a deep breath, positioned the bit, and began to drill deeper. Toward the brain. The first beads of sweat broke out on his forehead. He was drilling without CT confirmation, acting purely on his clinical judgment. He did not even know if he was tapping the right spot.

A sudden gush of blood spilled out of the hole and splattered the surgical drapes.

A nurse handed him a basin. He withdrew the drill and watched as a steady stream of red drained out of the skull and gathered in a glistening pool in the basin. He’d tapped the right place. With every trickle of blood, the pressure was easing from Debbie Haning’s brain.

He released a deep breath, and the tension suddenly eased from his shoulders, leaving his muscles spent and aching.

‘Get the bone wax ready,’ he said. Then he put down the drill and reached for the suction catheter.

A white mouse hung in midair, as though suspended in a transparent sea. Dr Emma Watson drifted toward it, slender-limbed and graceful as an underwater dancer, the curlicue strands of her dark brown hair splayed out in a ghostly halo. She grasped the mouse and slowly spun around to face the camera. She held up a syringe and needle.

The footage was over two years old, filmed aboard the shuttle Atlantis during STS 141, but it remained Gordon Obie’s favorite PR film, which is why it was now playing on all the video monitors in NASA’s Teague Auditorium. Who wouldn’t enjoy watching Emma Watson? She was quick and lithe, and she possessed what one could only call sparkle, with the fire of curiosity in her eyes. From the tiny scar over her eyebrow, to the slightly chipped front tooth (a souvenir, he’d heard, of reckless skiing) her face was a record of an exuberant life. But to Gordon, her primary appeal was her intelligence. Her competence. He had been following Emma’s NASA career with an interest that had nothing to do with the fact she was an attractive woman.

As director of Flight Crew Operations, Gordon Obie wielded considerable power over crew selection, and he strove to maintain a safe—some would call it heartless—emotional distance from all his astronauts. He had been an astronaut himself, twice a shuttle commander, and even then he’d been known as the Sphinx, an aloof and mysterious man not given to small talk. He was comfortable with his own silence and relative anonymity. Although he was now sitting onstage with an array of NASA officials, most of the people in the audience did not know who Gordon Obie was. He was here merely for set decoration. Just as the footage of Emma Watson was set decoration, an attractive face to hold the audience’s interest.

The video suddenly ended, replaced on the screen with the NASA logo, affectionately known as the meatball, a star-spangled blue circle embellished with an orbital ellipse and a forked slash of red. NASA administrator Leroy Cornell and JSC director Ken Blankenship stepped up to the lectern to field questions. Their mission, quite bluntly, was to beg for money, and they faced a skeptical gathering of congressmen and senators, members of the various subcommittees that determined NASA’s budget. For the second straight year, NASA had suffered devastating cutbacks, and lately an air of abject gloom wafted through the halls of Johnson Space Center.

Gazing at the audience of well-dressed men and women, Gordon felt as though he were staring at an alien culture. What was wrong with these politicians? How could they be so shortsighted? It bewildered him that they did not share his most passionate belief: What sets the human race apart from the beasts is man’s hunger for knowledge. Every child asks the universal question: Why? They are programmed from birth to be curious, to be explorers, to seek scientific truths.

Yet these elected officials had lost the curiosity that makes man unique. They’d come to Houston not to ask why, but why should we?

It was Cornell’s idea to woo them with what he cynically called ‘the Tom Hanks tour,’ a reference to the movie Apollo 13, which still ranked as the best PR NASA had ever known. Cornell had already presented the latest achievements aboard the orbiting International Space Station. He’d let them shake the hands of some real live astronauts. Wasn’t that what everyone wanted? To touch a golden boy, a hero? Next there’d be a tour of Johnson Space Center, starting with Building 30 and the Flight Control Room. Never mind the fact that this audience couldn’t tell the difference between a flight console and a Nintendo set; all that gleaming technology would surely dazzle them and make them true believers.

But it isn’t working, thought Gordon in dismay. These politicians aren’t buying it.

NASA faced powerful opponents, starting with Senator Phil Parish, sitting in the front row. Seventysix years old, an uncompromising hawk from South Carolina, Parish’s first priority was preserving the defense budget, NASA be damned. Now he hauled his three-hundred-pound frame out of his seat and stood up to address Cornell in a gentleman’s drawl.

‘Your agency is billions of dollars overbudget on that space station,’ he said. ‘Now, I don’t think the American people expected to sacrifice their defense capabilities just so you can tinker around up there with your nifty lab experiments. This is supposed to be an international effort, isn’t it? Well, far as I can see, we-all are picking up most of the tab. How am I supposed to justify this white elephant to the good folks of South Carolina?’

NASA administrator Cornell responded with a camera-ready smile. He was a political animal, the glad-hander whose personal charm and charisma made him a star with the press and in Washington, where he spent most of his time cajoling Congress and the White House for more money, ever more money, to fund the space agency’s perennially insufficient budget. His was the public face of NASA, while Ken Blankenship, the man in charge of day-to-day operations at JSC, was the private face known only to agency insiders. They were the yin and yang of NASA leadership, so completely different in temperament it was hard to imagine how they functioned as a team. The inside joke at NASA was that Leroy Cornell was all style and no substance, and Blankenship was all substance and no style.

Cornell smoothly responded to Senator Parish’s question. ‘You asked why other countries aren’t contributing. Senator, the answer is, they already have. This truly is an international space station. Yes, the Russians are badly strapped for cash. Yes, we had to make up the difference. But they’re committed to this station. They’ve got a cosmonaut up there now, and they have every reason to help us keep ISS running. As for why we need the station, just look at the research that’s being conducted in biology and medicine. Materials science. Geophysics. We’ll see the benefits of this research in our own lifetimes.’

Another member of the audience stood, and Gordon felt his blood pressure rise. If there was anyone he despised more than Senator Parish, it was Montana congressman Joe Bellingham, whose Marlboro Man good looks couldn’t disguise the fact he was a scientific moron. During his last campaign, he’d demanded that public schools teach Creationism. Throw out the biology books and open the Bible instead. He probably thinks rockets are powered by angels.

‘What about all that sharing of technology with the Russians and Japanese?’ said Bellingham. ‘I’m concerned that we’re giving away high-tech secrets for free. This international cooperation sounds high-minded and all, but what’s to stop them from turning right around and using the knowledge against us? Why should we trust the Russians?’

Fear and paranoia. Ignorance and superstition. There was too much of it in the country, and Gordon grew depressed just listening to Bellingham. He turned away in disgust.

That’s when he noticed a somber-faced Hank Millar step into the auditorium. Millar was head of the Astronaut Office. He looked straight at Gordon, who understood at once that a problem was brewing.

Quietly Gordon left the stage, and the two men stepped out into the hallway. ‘What’s going on?’

‘There’s been an accident. It’s Bill Haning’s wife. We hear it doesn’t look good.’

‘Jesus.’

‘Bob Kittredge and Woody Ellis are waiting over in Public Affairs. We all need to talk.’

Gordon nodded. He glanced through the auditorium door at Congressman Bellingham, who was still blathering on about the dangers of sharing technology with the Commies. Grimly he followed Hank out the auditorium exit and across the courtyard, to the next building.

They met in a back office. Kittredge, the shuttle commander for STS 162, was flushed and agitated. Woody Ellis, flight director for the International Space Station, appeared far calmer, but then, Gordon had never seen Ellis look upset, even in the midst of crisis.

‘How serious was the accident?’ Gordon asked.

‘Mrs Haning’s car was in a giant pileup on I-45,’ said Hank. ‘The ambulance brought her over to Miles Memorial. Jack McCallum saw her in the ER.’

Gordon nodded. They all knew Jack well. Although he was no longer in the astronaut corps, Jack was still on NASA’s active flight surgeon roster. A year ago, he had pulled back from most of his NASA duties, to work as an ER physician in the private sector.

‘Jack’s the one who called our office about Debbie,’ said Hank.

‘Did he say anything about her condition?’

‘Severe head injury. She’s in ICU, in a coma.’

‘Prognosis?’

‘He couldn’t answer that question.’ There was a silence as they all considered what this tragedy meant to NASA. Hank sighed. ‘We’re going to have to tell Bill. We can’t keep this news from him. The problem is…’ He didn’t finish. He didn’t need to; they all understood the problem.

Bill Haning was now in orbit aboard ISS, only a month into his scheduled four-month stay. This news would devastate him. Of all the factors that made prolonged habitation in space difficult, it was the emotional toll that NASA worried about most. A depressed astronaut could wreak havoc on a mission. Years before, on Mir, a similar situation had occurred when Cosmonaut Volodya Dezhurov was informed of his mother’s death. For days, he’d shut himself away in one of Mir’s modules and refused to speak to Mission Control Moscow. His grief had disrupted the work of everyone aboard Mir.

‘They have a very close marriage,’ said Hank. ‘I can tell you now, Bill’s not going to handle this well.’

‘You’re recommending we replace him?’ asked Gordon.

‘At the next scheduled shuttle flight. He’ll have a tough enough time being stuck up there for the next two weeks. We can’t ask him to serve out his full four months.’ Hank added quietly, ‘They have two young kids, you know.’

‘His backup for ISS is Emma Watson,’ said Woody Ellis. ‘We could send her up on STS 160. With Vance’s crew.’

At the mention of Emma’s name, Gordon was careful not to reveal any sign of special interest. Any emotion whatsoever. ‘What do you think about Watson? Is she ready to go up three months early?’

‘She’s slated to relieve Bill. She’s already up to speed on most of the onboard experiments. So I think that option is viable.’

‘Well, I’m not happy about it,’ said Bob Kittredge.

Gordon gave a tired sigh and turned to the shuttle commander. ‘I didn’t think you would be.’

‘Watson’s an integral part of my crew. We’ve crystallized as a team. I hate to break it up.’

‘Your team’s three months away from launch. You have time to make adjustments.’

‘You’re making my job hard.’

‘Are you saying you can’t get a new team crystallized in that time?’

Kittredge’s mouth tightened. ‘All I’m saying is, my crew is already a working unit. We’re not going to be happy about losing Watson.’

Gordon looked at Hank. ‘What about the STS 160 crew? Vance and his team?’

‘No problem from their end. Watson would just be another passenger on middeck. They’d deliver her to ISS like any other payload.’

Gordon thought it over. They were still talking about options, not certainties. Perhaps Debbie Haning would wake up fine and Bill could stay on ISS as scheduled. But like everyone else at NASA, Gordon had taught himself to plan for every contingency, to carry in his head a mental flow chart of what actions to follow should a, b, or c occur.

He looked at Woody Ellis for final confirmation. Woody gave a nod.

‘Okay,’ said Gordon. ‘Find me Emma Watson.’

She spotted him at the far end of the hospital hallway. He was talking to Hank Millar, and though his back was turned to her and he was wearing standard green surgical scrubs, Emma knew it was Jack. Seven years of marriage had left ties of familiarity that went beyond the mere recognition of his face.

This was, in fact, the same view she’d had of Jack McCallum the first time they’d met, when they’d both been ER residents in San Francisco General Hospital. He had been standing at the nurses’ station, writing in a chart, his broad shoulders sloping from fatigue, his hair ruffled as though he’d just rolled out of bed. In fact, he had; it was the morning after a hectic night on call, and though he was unshaven and bleary-eyed, when he’d turned and looked at her for the first time, the attraction between them had been instantaneous.

Now Jack was ten years older, his dark hair was threaded with gray, and fatigue was once again weighing down on his shoulders. She had not seen him in three weeks, had spoken to him only briefly on the phone a few days ago, a conversation that had deteriorated into yet another noisy disagreement. These days they could not seem to be reasonable with each other, could not carry on a civilized conversation, however brief.

So it was with apprehension that she continued down the hall in his direction.

Hank Millar spotted her first, and his face instantly tensed, as though he knew a battle was imminent, and he wanted to get the hell out of there before the shooting started. Jack must have seen the change in Hank’s expression as well, because he turned to see what had inspired it.

At his first glimpse of Emma, he seemed to freeze, a spontaneous smile of greeting half-formed on his face. It was almost, but not quite, a look of both surprise and gladness to see her. Then something else took control, and his smile vanished, replaced by a look that was neither friendly nor unfriendly, merely neutral. The face of a stranger, she thought, and that was somehow more painful than if he had greeted her with outright hostility. At least then there would’ve been some emotion left, some remnant, however tattered, of a marriage that had once been happy.

She found herself responding to his flat look with an expression that was every bit as neutral. When she spoke, she addressed both men at the same time, favoring neither.

‘Gordon told me about Debbie,’ she said. ‘How is she doing?’

Hank glanced at Jack, waiting for him to answer first. Finally Hank said, ‘She’s still unconscious. We’re sort of holding a vigil in the waiting room. If you want to join us.’

‘Yes. Of course.’ She started toward the visitors’ waiting room.

‘Emma,’ Jack called out. ‘Can we talk?’

‘I’ll see you both later,’ said Hank, and he made a hasty retreat down the hall. They waited for him to disappear around the corner, then looked at each other.

‘Debbie’s not doing well,’ said Jack.

‘What happened?’

‘She had an epidural bleed. Came in conscious and talking. In a matter of minutes, she went straight downhill. I was busy with another patient. I didn’t realize it in time. Didn’t drill the burr hole until…’ He paused and looked away. ‘She’s on a ventilator.’

Emma reached out to touch him, then stopped herself, knowing that he would only shake her off. It had been so long since he’d accepted any words of comfort from her. No matter what she said, how sincerely she meant it, he would regard it as pity. And that he despised.

‘It’s a hard diagnosis to make, Jack,’ was all she could say.

‘I should have made it sooner.’

‘You said she went downhill fast. Don’t second-guess yourself.’

‘That doesn’t make me feel a hell of a lot better.’

‘I’m not trying to make you feel better!’ she said in exasperation. ‘I’m just pointing out the simple fact that you did make the right diagnosis. And you acted on it. For once, can’t you cut yourself some slack?’

‘Look, this isn’t about me, okay?’ he shot back. ‘It’s about you.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Debbie won’t be leaving the hospital anytime soon. And that means Bill…’

‘I know. Gordon Obie gave me the heads-up.’

Jack paused. ‘It’s been decided?’

She nodded. ‘Bill’s coming home. I’ll replace him on the next flight.’ Her gaze drifted toward the ICU. ‘They have two kids,’ she said softly. ‘He can’t stay up there. Not for another three months.’

‘You’re not ready. You haven’t had time—’

‘I’ll be ready.’ She turned.

‘Emma.’ He reached out to stop her, and the touch of his hand took her by surprise. She looked back at him. At once he released her.

‘When are you leaving for Kennedy?’ he asked.

‘A week. Quarantine.’

He looked stunned. He said nothing, still trying to absorb the news.

‘That reminds me,’ she said. ‘Could you take care of Humphrey while I’m gone?’

‘Why not a kennel?’

‘It’s cruel to keep a cat penned up for three months.’

‘Has the little monster been declawed yet?’

‘Come on, Jack. He only shreds things when he’s feeling ignored. Pay attention to him, and he’ll leave your furniture alone.’

Jack glanced up as a page was announced over the address system: ‘Dr McCallum to ER. Dr McCallum to ER.’

‘I guess you have to go,’ she said, already turning away.

‘Wait. This is happening so fast. We haven’t had time to talk.’

‘If it’s about the divorce, my lawyer can answer any questions while I’m gone.’

‘No.’ He startled her with his sharp note of anger. ‘No, I don’t want to talk to your lawyer!’

‘Then what do you need to tell me?’

He stared at her for a moment, as though hunting for words. ‘It’s about this mission,’ he finally said. ‘It’s too rushed. It doesn’t feel right to me.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘You’re a last-minute replacement. You’re going up with a different crew.’

‘Vance runs a tight ship. I’m perfectly comfortable with this launch.’

‘What about on the station? This could stretch your stay to six months in orbit.’

‘I can deal with it.’

‘But it wasn’t planned. It’s been thrown together at the last minute.’

‘What are you saying I should do, Jack? Wimp out?’

‘I don’t know!’ He ran his hand through his hair in frustration. ‘I don’t know.’

***

They stood in silence for a moment, neither one of them quite sure what to say, yet neither one ready to end the conversation. Seven years of marriage, she thought, and this is what it’s come to. Two people who can’t stay together, yet can’t walk away from each other. And now there’s no time left to work things out between us.

A new page came over the address system: ‘Dr McCallum stat to ER.’

Jack looked at her, his expression torn. ‘Emma—’

‘Go, Jack,’ she urged him. ‘They need you.’

He gave a groan of frustration and took off at a run for the ER.

And she turned and walked the other way.