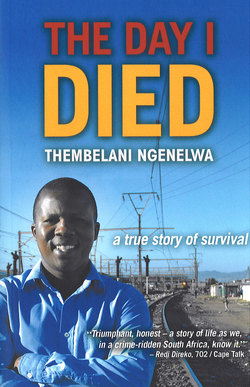

Читать книгу The Day I Died - Thembelani Ngenelwa - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3 The day

ОглавлениеThe day

It’s amazing how you sometimes wake up feeling so good about yourself for no particular reason. It’s a feeling that takes you through the day and makes you excited about life. On Wednesday, 1 October 2003, I woke up feeling like this.

At about half past eight I jumped out of bed, looking forward to the day ahead. The guys had already all gone to work, leaving only Bongani, Khanyisa and myself in the flat, and it was quiet as the other two were still sleeping.

I stepped outside and felt the warm Johannesburg sunshine, took a deep breath of morning air and told myself that this would be a good day for me. Then I looked up at the sky. It was clear but there was one little dark cloud that hung there like a misplaced dirty sock in the kitchen. This little cloud was starting to spread and it was spoiling what was otherwise promising to be a beautiful day. In our culture they regard a dark cloud as a sign that somebody is about to die, but it is also a clear sign that it is about to rain and rain is a symbol of new life. Because of this I didn’t know how to interpret the sky and went inside.

I had called my parents the previous day to let them know that I was in Johannesburg. They knew my reasons and never had a problem with my being in Jozi as they knew my friends. My mother had answered the phone. Usually she is always happy to hear my voice over the phone, but this particular day she didn’t sound happy at all, even though I had recently deposited some money for her. In fact, she sounded very worried.

“Sisi, you sound uncomfortable, is there anything bothering you?” I asked.

“Nothing, mntwan’am, there is no problem with me, just look very well after yourself whilst you are still there,” she replied.

However, even though my mother didn’t seem happy, she wished me well in my endeavours and thanked me for the money that I had deposited for them. I knew that I had her blessings and prayers. I had an urge to talk to my father and my brothers as well, but my mother was the only one at home so I said my goodbyes.

After speaking to my mother I had gone to the employment agencies again to see if they didn’t have any more vacancies. By this stage I had managed to secure an appointment with an IT manager from one of the companies I had visited in Kempton Park. The appointment for an interview was scheduled for that coming Friday. I was really looking forward to impressing them, but that didn’t mean that I could stop looking.

After I had finished at the last agency I decided to go to Wits University and visit their careers centre. I was hoping to get some advice. That is where I met Mthetho, a friend who had also studied at UWC. He was working as a clinical psychologist and lecturer. He took me to his office, where we chatted for hours, reminiscing about our days back in the Cape and our future ambitions. We shared a common goal, that of putting our humble backgrounds behind us and putting our beloved Eastern Cape on the map.

I had really enjoyed seeing the success that Mthetho had made of himself, but Tuesday had been a busy day and I had decided to take it easy that Wednesday morning. Bongani wanted to take a stroll into town and visit his girlfriend who stayed in a small suburb called Delville, on the outskirts of Germiston, and I decided to go with him.

On our way back, I received a call from my friend who stayed in Five. She asked me when I was planning to visit them, so I told her that I would as soon as my friends came back from work. I was keen to see Five again because the first time I had visited Gauteng, in 2000, I had shared a two-bedroom shack there with Khaya, Siviwe and Zolisa. Five was the first place that I had known in Gauteng and I had made lots of friends in the area. The place was a hive of activity and the people were so positive about life despite their circumstances. People came from all walks of life, with different cultures and languages, but they all mingled together and took care of one another. They would call one another makhi, meaning “good neighbour”, and everyone knew everyone else.

I remember one day while I was staying there, the community had gathered to support one boy who had passed his matric with an exemption. The young man’s parents could never afford to send him to university, but the community had managed to raise some funds to send the boy to study further.

It is true that there were also a lot of shebeens in Five, but I hardly saw any crime of any kind amongst the community members and, in all the days that I stayed there, I don’t remember seeing any violence. There was always a good atmosphere in the area, so good in fact that you would go to town and rush back as soon as you finished your shopping just to enjoy the place. You didn’t have to wait for an invitation to go to any party in the neighbourhood, you could just rock up and the partygoers would just welcome and entertain you. The people were true to themselves and nobody looked down on anyone else.

So you must understand that this place was very close to my heart. I felt that for me to feel like I had really arrived in Gauteng, I had to shake the hands of our ex-neighbours and old friends. It would be some sort of homecoming. I would also get a chance to see some people from my beloved Engcobo who stayed there. All of my friends in Germiston originally came from the other areas of the Eastern Cape, so I was really excited about seeing my abakhaya.

Bongani and I decided to cook so that by the time the guys got back from work the food would be ready. This way they wouldn’t waste time; they’d just have their meals and we would head straight to the township.

We had also been invited to a party in one of the flats in Germiston, so we decided we would go to Five first and attend the party later. We knew that we would visit the township again at the weekend, and probably spend the whole of Saturday afternoon there, so it didn’t matter that this was going to be a short visit. I decided on the easiest of meals: mince mixed with potatoes. I knew that this wouldn’t take too long to make and wouldn’t expose my cooking skills, or lack thereof – I am also not the greatest cook on earth.

Round about five in the afternoon Khaya and Zolisa arrived from work. Khaya, in particular, was so excited about visiting Five that he ended up eating only half of his meal. Strangely, though, Zolisa didn’t want to go to Five, claiming that he was utterly exhausted from work. I call this strange because he was usually the first to want to visit somewhere, even if he didn’t know the people we were visiting. Sometimes he would even volunteer to pay the taxi fare, but on this day, when we wanted to go to a place that was only walking distance away, the place that he knew better than any of us, he just didn’t feel like going.

Khaya’s younger brother, Khanyisa, also wanted to come with us. We usually let him come along, but that afternoon I just didn’t want him there. I told him he had to stay behind and wait until we came back, telling him that we would go to the flat party together later.

I still don’t know why I refused to let him come with us when even his elder brother wanted him to tag along. I suppose I didn’t want this young “laaitie” spoiling the big boys’ fun.

While Khaya and Bongani did everything in a hurry I went upstairs to the public phones to confirm that we were on our way. Then Khaya, Bongani and I were in the street, greeting our friends as we passed with smiles as wide as the Amazon river.

Since it was getting colder, I had taken Bongani’s green jacket. I hadn’t brought any warm clothing with me as I had expected Johannesburg to be very hot around October time. Underneath Bongani’s jacket I was only wearing the black tracksuit I usually wore for our daily jogs. I had decided to look as ordinary as possible, so that I wouldn’t attract any attention. We had also decided to leave our cellphones and all our important possessions behind, in case we got robbed or something bad happened.

We went past the big Enterprise meat factory, heading for the industrial area near the railway lines. The area was so quiet that we could hear our own footsteps. We were walking fast because it was getting colder, busy cracking jokes and reminiscing about the last time we were all in Five together.

Soon we could see a few shacks and, as we went closer, we left the main road and took a path that would take us straight to the township. On either side of the path, the grass was overgrown and dry. There was a railway bridge on our right-hand side and to get to the township we had to walk alongside the bridge and across the railway lines.

As we approached the bridge, we came across five guys who were going towards the area we were coming from. I was walking behind Bongani and Khaya because they were more familiar with the path than I was, so I never really bothered to look at the other guys’ faces. I didn’t see any need to do so. We were just going our way, minding our own business. They were also going their own way, minding their own business. That’s what I kept telling myself but, in all honesty, I sensed danger.

As they approached, they seemed to be engaged in conversation. You could see this from the way the one in front kept looking behind to check on the others. He was wearing a maroon T-shirt and khaki Dickies pants. Strangely enough, he was the only one that I seemed to notice. Somehow he looked like the leader of the group. I cannot remember a single thing about the rest of them. This guy just stood out, for whatever reason.

“Hola, bafethu,” they greeted us as they passed by.

We returned the greeting and they continued with their journey, but I must admit that after those guys had passed I had an uneasy feeling once more and my heart started pumping faster.

I’m not usually someone who scares easily, but that day I just felt afraid. I couldn’t help having a quick look back, just to check that they weren’t up to something, just to be sure, but when I glanced over my shoulder they were just continuing with their journey towards town.

Reassured, I tried to concentrate on the conversation we were having. Neither Khaya nor Bongani seemed bothered about anything and I didn’t want to be seen as the scared little guy from Cape Town. After all, I had been to Five before and I had also been to a lot of supposedly dangerous townships in Cape Town. I didn’t fear any township.

We crossed the railway lines and entered the settlement. I felt relieved as we approached and we all started walking a little faster now we were on more familiar ground.

I smiled as I saw the shacks; some people had made their homes from planks and some from corrugated iron, but all of the shacks had been painted in different colours. I loved the assortment of colours that they boasted. But it was also obvious that the place had changed a lot. There was a big empty space behind the township that had once housed many people. Most of the shacks had been removed; presumably the owners had been moved to the new RDP houses in other areas. The shacks that used to be next to ours were no longer there, but I noticed a green shack that I recognised, opposite the water tap we used back in 2000. People were still fetching water from the same tap.

We went past a spaza whose owner used to call me mkhaya, since he was originally from Engcobo. We asked the shopkeeper about him, but he told us he was the new owner as the previous owner had sold the shop and moved to a different area.

Finally we saw the blue shack we were looking for. We knocked at the open door and found Nomaphelo and her cousin, who was visiting from East London, inside. As soon as we were in, she made a phone call and within minutes Mheza came in with a wide smile that went from ear to ear. I started laughing out loud when he started his trademark “salute”, but at first he didn’t recognise me as the light wasn’t bright enough. That was until I called him Mathintitha, the pet name I had given him back in 2000. Then he knew who I was immediately and shouted back, “Young boy, are you back from the Cape?”

We shook hands and started chatting. Mheza had a stutter, yet he wanted us to listen to him all the time. He was even more excited when he saw me as he wasn’t aware that I was in town. We started reminiscing about the last time I was there and it was nice. Then they began to tell us of how the place had changed and how dangerous it had become. When I asked about my abakhaya I was informed that they had moved to the nearby area called Rondebult.

After chatting to Mheza we decided to leave early so that we could get back to Germiston for the flat party and he could attend a memorial service for a lady who had been stabbed to death, apparently by a jealous boyfriend. Nomaphelo asked if she could come with us so that she could see where we stayed. We had already told her about the party in town that we were all going to, so she decided she’d rather go with us because she was

not going to go to work the following day. We said our goodbyes to Mheza while we waited for Nomaphelo to put on her jacket and then headed home the same way we had come.