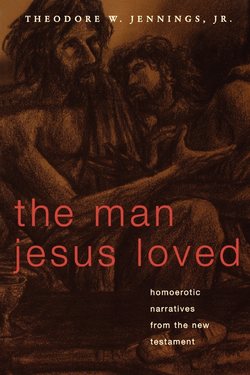

Читать книгу Man Jesus Loved - Theodore W. Jr. Jennings - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2 The Lover and His Beloved

ОглавлениеWhile the question of the identity of the beloved disciple and his role in the text is a not uncommon feature of commentaries on the Gospel of John, little is written about the nature of the relationship between Jesus and this person. A conspiracy of silence seems to surround this question. Yet the Gospel itself places all the weight on the nature or character of the relationship between Jesus and his beloved, rather than the disciple’s name or his “function.”

The text makes clear that among so many to whom Jesus had strong personal ties, one particular disciple was Jesus’ beloved. Along with Jesus’ teaching concerning the nature of God’s love and human love, and Jesus’ demonstrating and awakening of this love, one person was simply “the disciple he loved”—the beloved one for whom Jesus was the lover. When all is said and done, the fact that the text does indicate that Jesus was in this most definite and concrete and intimate sense a lover with a beloved is itself quite remarkable, even apart from the added information that this beloved was also another male. However, this added information has served to “hide” the relationship wherever homophobic or heterosexist presuppositions have prevailed. Indeed the erotophobic presuppositions of much traditional exegesis would have made it difficult to see Jesus as a lover with a beloved even if the beloved were female. But the taboos constructed by homophobia and heterosexism have rendered a reading of the relationship between Jesus and his beloved virtually impossible.1

In this chapter, I attempt what may be called a homoerotic reading of the relationship between Jesus and his beloved. The aim of such a reading is to see what sense it makes of these texts to read them as suggestive of what we might today label a homosexual or gay relationship.

Apart from the controversial nature of such a reading, two qualifications must be observed. First, I will not suggest what sexual practice, if any, served to mediate or express this relationship. As is true for other relationships, whether same-sex or cross-sex, the data in all but pornographic texts typically does not intrude into this sphere. In this chapter, the gay reading is not meant to foreclose the question of sexual practice one way or the other. This issue will occupy us in chapter 4.

The other qualification concerns the much vexed question of the “construction of homosexuality.” The suppositions concerning homosexual relations that are present in contemporary society cannot simply be read back into other cultures or periods of history. The term “homosexual,” as adjective or noun, is only a century old. As a noun, the term generally refers to persons who are disposed to find sexual fulfillment in relations with persons of the same biological sex as themselves. Cultural and historical study has shown that the classification of persons as either homosexual or heterosexual (or, more recently, bisexual) has virtually no precedent in premodern culture. Certainly knowledge of same-sex sexual attraction or sexual practice existed, but the way in which these were understood, thought about, poeticized, and so on was in quite different terms—whether same-sex sexual attraction and practice were regarded as obligatory, preferable, permissible, odd, or prohibited.

In the modern period, persons who are drawn to same-sex erotic relations are often presumed averse to “heterosexual” relations. This presumption clearly does not reflect the view of most cultures and historical epochs for which we have data. Moreover, the contemporary model of same-sex relationships in our society emphasizes relations between peers. But for Greek antiquity, medieval Japan, and tribal Melanesian society, cross-generational or pederastic structures were normative.

For our study, we should not read back into the sources stereotypes from our own culture concerning sexual structures, practices, or preferences. At the same time, we must use some language to identify the point of contact we wish to make with another epoch or culture. Extreme relativism can produce only the silence of cultural solipsism. The difficulty we face here is not different in kind from the difficulty of speaking about “marriage” or “family” or “the poor” or “justice.” In each case, modern ways of understanding these categories differ markedly from those of other epochs and other cultures. Thus, without either ignoring or being paralyzed by cultural and historical differences, the “point of contact” with the text that we seek to illumine is the love of one man for another that is “more” than friendship and which does not foreclose erotic attraction or sexual expression.2

With these qualifications in mind, let us turn now to the texts to see how a homoerotic reading makes sense of the data that the Gospel of John presents.